From its earliest recordings in African, Indian, and Egyptian cultures, the hare, which later became interchangeable with the rabbit, has been recognized as a symbol of generative powers.

In the ancient Greco-Roman world, the hare symbolized fertility, as well as love and lust. The hare was the favored sacrifice to the gods of love, Aphrodite and Eros.[1] Consumption of the animal’s flesh was thought to enhance the beauty in the eater for several days. The animal’s body was also incorporated into medicines meant to cure conditions connected with sex.

Hares and rabbits were known as prolific breeders, but the classical world often exaggerated the creature’s capacity for reproduction. Aristotle, for example, believed the rabbit was capable of superfetation – that is, he thought a pregnant rabbit could become pregnant again, thereby gestating multiple litters at once. These ideas persisted into the Middle Ages, passed down by Aristotle and other philosophers such as Herodotus, as well as Pliny the Elder.

In his Naturalis historia, written during the first century, Pliny the Elder characterizes hares and rabbits as the only animals that superfetate, “rearing one leveret while at the same time carrying in the womb another clothed with hair and another bald and another still an embryo.” He also discusses how wild rabbits laid waste to Spain. Describing their fertility as “beyond counting,” he says that “they bring famine to the Balearic Islands by ravaging the crops.”[2]

England, however, did not share Spain’s poor experience with rabbits. Although hares are indigenous to the British Isles, rabbits are not. They were introduced to England by the Normans in the 13th century and were raised for their meat and fur.[3] They were also kept as pets and were a particular favorite of nuns.[4]

Rabbits did not initially thrive in the British climate, and they required careful tending by their owners, who constructed warrens for them. As Mark Bailey explains, “In modern usage the rabbit-warren refers to a piece of waste ground on which wild rabbits burrow, but in the Middle Ages it specifically meant an area of land preserved for the domestic or commercial rearing of game.”[5] These artificial burrows called “pillow-mounds” protected domestic rabbits from the elements and provided a dry, earthen enclosure that supported both survival and breeding.

Despite their modern reputation as pests, rabbit populations were primarily confined to privately owned warrens in medieval England. They were not considered vermin but, rather, valuable commodities, and they were protected by law. Poachers were a problem, as were the rabbit’s natural predators, which included the fox, stoat, weasel, polecat, and wildcat.

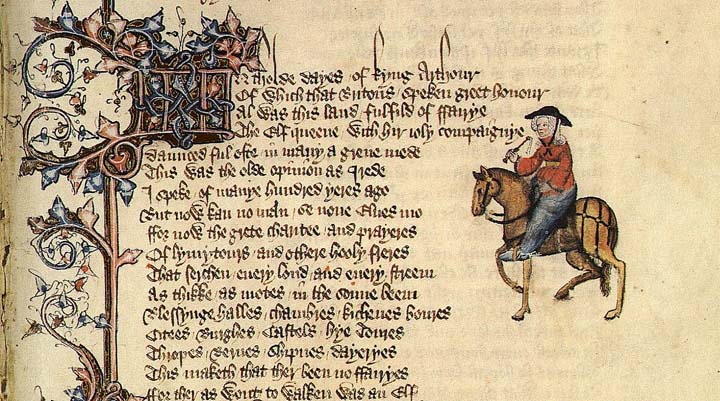

Yet in medieval English literature, rabbits retain their symbolic association with reproduction, as exemplified by Geoffrey Chaucer’s Parliament of Fowls, a Middle English poem dated to the mid-14th century. Set in a garden during springtime, the poem centers a congregation of birds that meets to select their mates and explores themes related to love and marriage, as well as breeding.

Rabbits, or “conyes,” are depicted at play amidst the gathering of birds:

On every bough the briddes herde I singe,

With voys of aungel in hir armonye,

Som besyed hem hir briddes forth to bringe;

The litel conyes to hir pley gonne hye. (Chaucer 190-93)[6]

I heard the birds on every branch singing

Like the voice of an angel in their harmony,

Some had their young beside them;

The little rabbits were busy at their play. (my translation)

Now virtually obsolete, the term coney was used in medieval England to differentiate an adult rabbit from a younger one. Deriving from the pun made possible by the Latin word for rabbit, cuniculus, and the Latin word for the female genitalia, cunnus, the term was also used as sexual slang in the medieval period and well beyond.[7] Essentially, coney, or cunny, was a crass term that referred to the vulva or vagina, to a woman or women, or to sexual intercourse.[8]

Despite its long-standing sexual symbolism, the rabbit was simultaneously imparted with sacred symbolism in the Middle Ages. In England, the rabbit became a symbol of purity when portrayed alongside the Virgin Mary. The animal also functioned as a symbol of salvation. As David Stocker and Margarita Stocker explain, “their sacred meaning is not as divorced from their profane meaning (libidinousness) as may at first appear. One the one hand, their symbolism of lust and fertility refers to the carnal body; on the other, their symbolism of salvation and resurrection refers to the ‘body of this death’ from which the soul is saved.”[9]

Indeed, the theologian and philosopher Saint Augustine, writing between 397 and 400 CE, connects the rabbit with Christianity, further attesting to how the animal’s sexual and spiritual symbolism culturally coexisted. Discussing the rabbit in relation to salvation, Saint Augustine renders the creature a symbol of cowardice. He describes the rabbit as “a small and weak animal” that is “cowardly” and then draws a parallel between the rabbit and the fearful man: “In that which he fears, man is a rabbit.”[10] Later in the Middle Ages, the rabbit “denoted a soldier who burrowed underground or someone who fled from his pursuers.”[11]

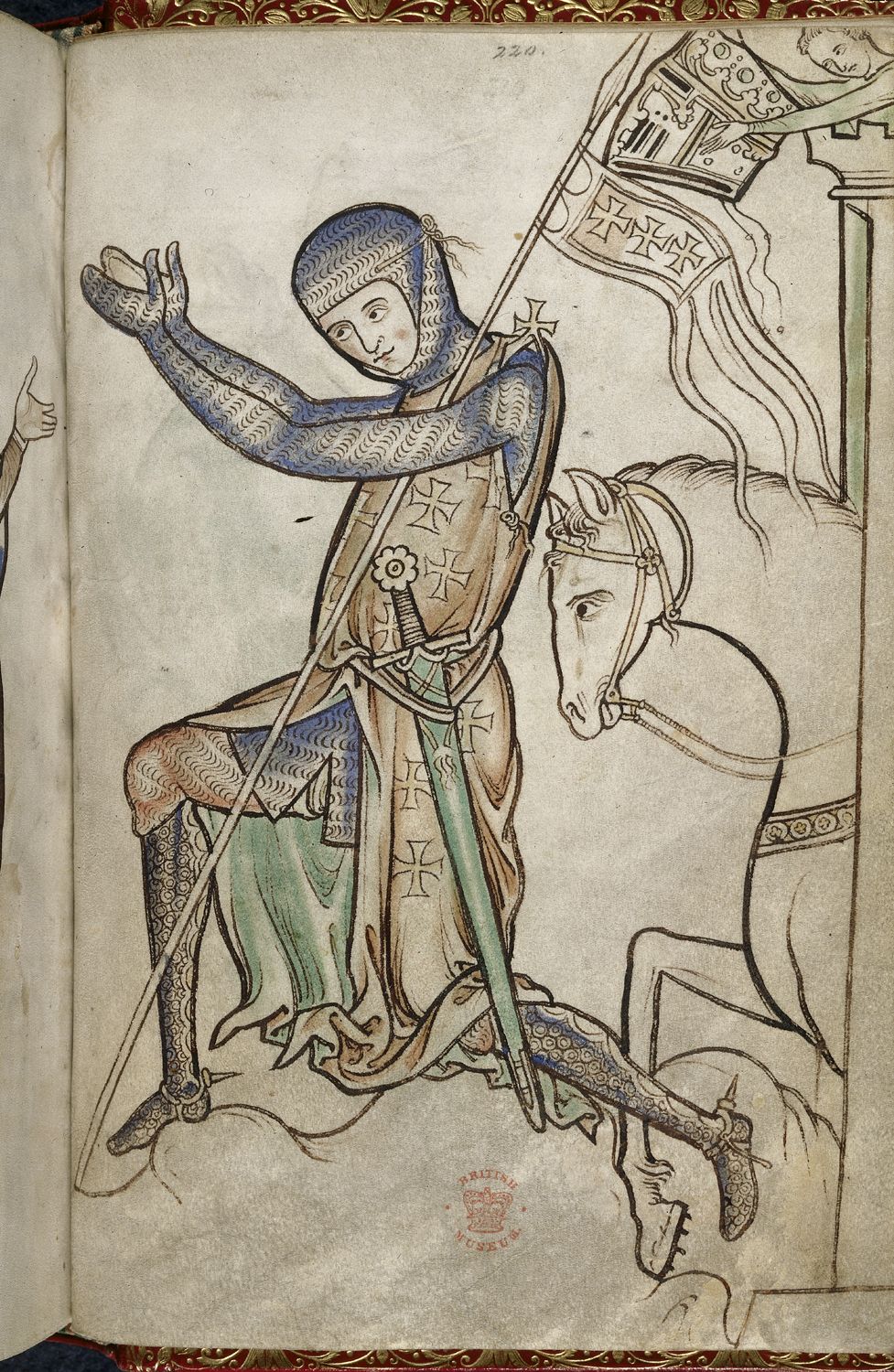

Perhaps the rabbit’s connection with cowardice, then, provides some insight into the images depicting bunnies as antagonistic and often murderous beasts in the margins of medieval manuscripts. Immortalized on screen by Monty Python’s Rabbit of Caerbannog and more recently popularized on social media, the rabbit adopts many forms and runs rampant across the pages of manuscripts from England and Europe.

Rabbits spar with knights, wield axes at kings, and lay siege to castles. They ride snails with human faces and carry hounds on their shoulders into battle. They beat, they behead, they hang, they flay. Ranging from delightfully strange to strangely sadistic, the images of rabbits enacting violence reveal a world turned topsy-turvy through their reversal of expectations.

But medieval bunnies are not all bad. In bestiaries, they pose timidly in their portraits or express fear as they flee from hunting dogs. They frequently adorn decorative borders sans weapons and sometimes appear surprisingly realistic, as in the stunning illumination from the Cocharelli Codex below.

Although the killer coney and the cowardly knight have become a familiar motif, it is not a reflection of the rabbit population ransacking the English countryside, as some might be inclined to suspect. After all, wild rabbits did not become abundant until centuries later. But whether turning the world upside down or nestled benignly within a manuscript border, rabbits in medieval marginalia showcase their multifacetednous as an enduring and aptly inexhaustible cultural symbol.

Emily McLemore, Ph.D.

Alumni Contributor, Department of English

[1] Claude K. Abraham, “Myth and Symbol: The Rabbit in Medieval France,” Studies in Philology, vol. 60, no. 4 (1963), pp. 589-597, at 589.

[2] Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Loeb Classical Library, at 153.

[3] Mark Bailey, “The Rabbit and the Medieval East Anglian Economy,” The Agricultural History Review, vol. 36, no. 1 (1988), pp. 1-20, at 1.

[4] Kathleen Walker-Meikle, Medieval Pets, Boydell Press (2012), pp. 14.

[5] Bailey, 2.

[6] Geoffrey Chaucer, Parliament of Fowls, http://www.librarius.com/parliamentfs.htm.

[7] Beryl Rowland, Animals with Human Faces: A Guide to Animal Symbolism, University of Tennessee Press (1973), pp. 135.

[8] cunny, n. Oxford English Dictionary.

[9] David Stocker and Margarita Stocker, “Sacred Profanity: The Theology of Rabbit Breeding and the Symbolic Landscape of the Warren,” World Archaeology, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 265-72, at 270.

[10] Stocker and Stocker, 271.

[11] Rowland, 135.