This piece accompanies CJ Jones‘ sung recitations and translation of Ave virginalis forma. Jones‘ contribution to our Medieval Poetry Project marks another exciting expansion as she bring a number of firsts to the project: the first Latin poem, the first Middle-High German poem, and the first song. She does not disappoint. Jones not only translates the song into modern English, she sings Ave virginalis forma in all three languages (Latin, Middle High German and modern English).

Translator’s preface:

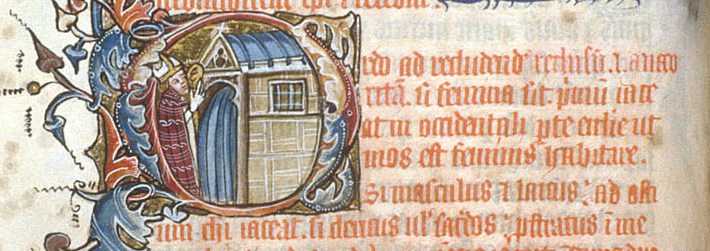

“Ave virginalis forma” (Analecta Hymnica, vol. 54, p. 379ff.) was composed in the first half of the fourteenth century and is attributed to an otherwise unattested Jacob, priest of Mühldorf. It was a highly complex and difficult poetic endeavor, both with regard to its poetic form and its classicizing and Greek vocabulary. Nevertheless, in the latter half of the fourteenth century the prolific songster known as “Der Mönch von Salzburg” (the monk from Salzburg) undertook to translate it into a German verse that maintained the poetic structure of the original Latin and could be sung more or less to the same melody. In attempting the same with modern English, I discovered just how difficult that is.

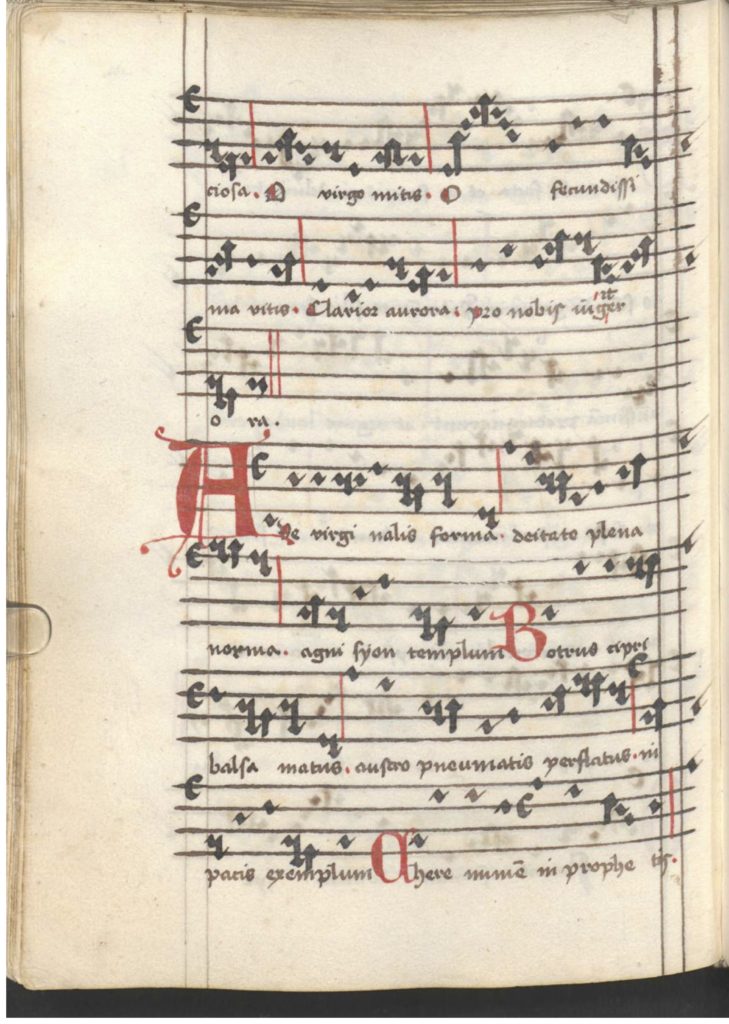

The chant is a sequence, a liturgical genre that was sung before the Gospel reading at Mass. (As far as I know, there is no evidence that “Ave virginalis forma” was actually sung liturgically, but formally it belongs to this genre.) Early sequences have very loose or no poetic form, but as the genre evolved, composers began to prefer texts with strict metrical forms and rhyme schemes. The first few verses of “Ave virginalis forma” fit the most popular poetic structure of the “new sequence” that was popular by the thirteenth century. The most significant characteristic that differentiates the sequence from the hymn is that sequence verses are paired, but the melody is through-composed. This means that verses 1 and 2 are sung to the same melody, but 3 has a new melody, repeated in verse 4, before yet a new melody is heard in verses 5 and 6, and so on. Within this overarching rule, there is some flexibility to repeat smaller melodic units and phrases. Jacob was sensitive to the relationship between the melody and the poetic form: for example, the closing line of the R and S verses is repeated for the following T and V pair and, accordingly, Jacob used the same end rhyme for all four verses. (Der Mönch von Salzburg did not notice the recycled melodic material and used different end rhymes for the two pairs; I tried my hardest to maintain the same rhyme for all four).

Jacob imposed an extra poetic constraint on himself: Ave virginalis forma is an abecedarium. Each verse begins with a letter of the alphabet (Ave, Botrus, Chere, Dei…). Der Mönch von Salzburg did follow this poetic constraint but for difficult letters simply took over the first word of the Latin verse and then set in with the German translation (Karissima / liebst aller lieb; Quis / wer). I permitted myself the same liberty. I should also note that both Jacob and der Mönch von Salzburg used the chi rho spelling of “Christ” for verse X, and I followed suit. Jacob also accomplished some real feats of poetic structure, which I was not able to imitate. The first and third lines of verses J and K rhyme both the first and second word, which neither the German nor the English manage (see also P and Q). Lines 2 and 4 of the L and K verses all end with internal double rhyme; der Mönch von Salzburg did a better job rendering this than I did. I settled on using rhyming syllables at the beginning and end of those lines. Finally, the paired N and O verses each incorporate an extraordinary sequence of internal rhyme, which neither der Mönch von Salzburg nor I were able to reproduce in German or English, although each of us gave it the old college try.

For the melody, I used two manuscripts of related provenance, Munich, Bavarian State Library, cgm 715 and cgm 716. Both manuscripts were produced in Bavaria toward the end of the fifteenth century and both were owned by the monastery of Tegernsee, although it is unlikely that either was produced there. I had to supplement and extrapolate from another manuscript for the German version because, due to an extraordinary eye-skip (from “vrowe” to “vrowe”), the scribe of cgm 715 left out the entirety of verse Q. The melody of the German differs slightly from the Latin – as do the melodies in other manuscripts containing the Latin sequence. If I were being true to medieval practice, I would have been looser with the melody for my English translation, as well.

I do not think that I have done justice to the beauty and complexity of the Latin sequence, neither in my sung recording nor in my translation. Still, in the process, I learned an enormous amount about stress and melodic shape, poetic flexibility, and Old Testament allegories for Mary. I owe thanks to Richard Fahey for encouraging me to take on this project, to Sean Martin for helping me record it, and to Christopher Miller for helping me edit the audio files.

Claire Taylor Jones

Assistant Professor of German

University of Notre Dame