[This post was written in the spring 2018 semester for Karrie Fuller's course on Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. It responds to the prompt posted here.]

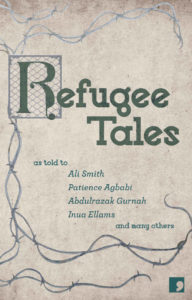

Open your morning newspaper or scroll through the news report that just popped into your inbox and there’s a good chance that one of today’s top stories surrounds the global refugee crisis. It’s today’s top story, it was yesterday’s, and it’s likely to be tomorrow’s too. With countless news stories dictating faceless facts and figures of the growing number of refugees, one UK organization – the Gatwick Detainees Welfare Group – decided to make things personal, drawing inspiration from an unlikely source: our good friend Geoffrey Chaucer and his work, The Canterbury Tales. Like The Canterbury Tales’cast of characters embarking on a religious pilgrimage and participating in a tale-telling contest along the way, a group of writers, poets, and journalists set out on their own pilgrimage across the UK, journeying in solidarity with refugees, asylum seekers, and immigration detainees. They stopped along the way to tell the stories of those who had walked that path before them; then those tales were compiled into the Refugee Tales. A look into the Canterbury Tales, specifically the “Man of Law’s Tale,” illustrates how the structure of storytelling is an effective mode for educating about the refugee crisis as well as how the issues of persecution and discrimination pervaded even Chaucer’s society hundreds of years ago.

Open your morning newspaper or scroll through the news report that just popped into your inbox and there’s a good chance that one of today’s top stories surrounds the global refugee crisis. It’s today’s top story, it was yesterday’s, and it’s likely to be tomorrow’s too. With countless news stories dictating faceless facts and figures of the growing number of refugees, one UK organization – the Gatwick Detainees Welfare Group – decided to make things personal, drawing inspiration from an unlikely source: our good friend Geoffrey Chaucer and his work, The Canterbury Tales. Like The Canterbury Tales’cast of characters embarking on a religious pilgrimage and participating in a tale-telling contest along the way, a group of writers, poets, and journalists set out on their own pilgrimage across the UK, journeying in solidarity with refugees, asylum seekers, and immigration detainees. They stopped along the way to tell the stories of those who had walked that path before them; then those tales were compiled into the Refugee Tales. A look into the Canterbury Tales, specifically the “Man of Law’s Tale,” illustrates how the structure of storytelling is an effective mode for educating about the refugee crisis as well as how the issues of persecution and discrimination pervaded even Chaucer’s society hundreds of years ago.

The Man of Law’s Tale follows Constance, a devout and pious Christian woman, on journeys across the seas and back; though she endures persecution, violence, and trial at each step, she remains steadfast in faith and eventually returns home. Two snapshots of Constance’s voyages speak directly to the experience of refugees and migrants throughout history. First, upon arriving in Syria, Constance is courted by the Sultan who is so taken by her and her faith that he converts to Christianity and urges his people to do the same. The Sultan’s mother, however, fears that Constance is trying to force her religion onto the Syrians, saying: “What sholde us tyden of this newe lawe / But thraldom to oure bodies and penance, And afterward in helle to be drawe” (Chaucer, 337-339). She fears that this new member of the community, who has brought in her own set of beliefs and practices different from their own, will overtake the native culture, ruin its integrity, and enslave the people in a life they do not want. In retaliation, the Sultan’s mother orders a merciless massacre of all who converted – including her own son – and Constance is forced to flee. This kind of violent religious persecution was not uncommon at the time and it endures today; there is a persistent danger in demonstrating foreign practices or customs for fear of persecution. It is rooted in a lack of understanding of other cultures as well as a desire to preserve one’s own culture, at any cost.

The second important episode of Constance’s story finds her as a refugee just landed in a pagan country. Knowing that she has arrived in an environment hostile to Christians (“In al that lond no Cristen dorste route; / Alle Cristen folk been fled fro that contree” (Chuacer 540-541), Constance is forced to hide her faith and lie about part of who she is in order to appear less different and threatening – to save herself from the kind of violence she faced in Syria. This is a common experience among refugees who feel the need to blend in to their new communities and avoid standing out for fear that they will be discovered and apprehended. The need for safety eclipses all other needs, and many refugees and immigrants are forced to hide or even give up integral pieces of themselves in order to avoid punishment, ridicule, or even removal.

[Disclaimer: Religious persecution ran rampant during the Middle Ages, so a story such as this is not uncommon; however, this tale is problematic in its telling. While the tale is certainly plausible, it is necessary to note that it is inherently malicious in its portrayal of other religions – i.e. the portrayals of the Sultan’s vicious mother and of the pagans are not flattering and are, in fact, exaggerated, rendering the tale itself spiteful and discriminatory against non-Christians and demonstrating the multi-faceted and widespread persecutions from all angles in Chaucer’s time. For more on the Man of Law’s tale, check out Meggie Kollitz’s piece on "Islamophobic Rhetoric in Chaucer: Not Just ‘A Thing of the Past.’”]

The Refugee Tales adopt the overall structure of the larger Canterbury Tales and delve deep into the specific issues of the persisting refugee crisis seen in the “Man of Law’s Tale.” Having met with and listened to a number of refugees, asylum seekers, and immigration detainees in the UK, the taletellers of the Refugee Tales set off across the country to tell the stories they had learned. One such story is “The Detainee’s Tale“ in which a writer, Ali Smith, discusses her encounter with a man who was indefinitely detained and her subsequent visit to a detention facility. She writes as if telling the story to the detained man himself, using “you” to refer to him and speaking of herself in the first person: “The first thing that happens, you tell me, is that school stops” (Smith). This point of view draws the reader in and puts us into the detainee’s shoes, as if Smith is telling us our own experience. The majority of the tales, in fact, are told in first person – a significant difference from the original Canterbury Tales, which does not use first person in any of the tales. This important change renders each tale much more personal and each subject more real. It gives a real voice to silenced refugees and migrants while protecting their anonymity. Additionally, the title of the tale (in this case, the “Detainee’s Tale”) names the subject of the story, rather than the teller, shifting the focus from teller to tale (in this case, the Detainee, rather than Smith). While borrowing the structure of the Canterbury Tales, the Refugee Tales tell much more personal and heart-wrenching stories that focus on giving a voice to these people (not stock characters) who otherwise would go unheard.

Among the greatest attributes of the Canterbury Tales is its insight into the vast array of characters living in the Middle Ages, as well as the different values and issues of the time. Similarly, the Refugee Tales spotlight a commonly undocumented section of today’s social spectrum and showcase important social problems and values. Looking back on the Canterbury Tales, it is easy to cringe at and criticize many of the implied social norms. We can look at the society painted by Chaucer and realize it wasn’t all that pretty. But that forces us to acknowledge the stains on the tapestry of human history. We should never sanitize the past and bleach out the bad parts; rather we must recognize them and learn from them. Similarly, there is a need to document all parts of our current history – even the parts that are not so pretty. The Refugee Tales does just that. These tales detail a trying time in our world and shed light on a crisis in human dignity. This particular portrayal of the issue, however, illuminates the presence of humanity, compassion, and hope amidst that crisis. We have seen that the social problems of persecution and discrimination have persisted since Chaucer’s time, and even before; the Refugee Tales show that, yes, those issues still exist, but how we view and approach them has evolved and we are finding new ways to solve them once and for all.

Claire Doyle

University of Notre Dame

Works Cited:

Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Man of Law’s Tale, from the Canterbury Tales. Edited by Robert Boenig and Andrew Taylor, 2ndEdition, Broadview Press, 2012.

Herd, David, and Anna Pincus, editors. Refugee Tales. Comma Press, 2016.

Smith, Ali. “The Detainee’s Tale by Ali Smith: ‘I Thought You Would Help Me’.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 28 June 2015, www.theguardian.com/books/2015/jun/27/ali-smith-so-far-the-detainees-tale-extract.

To Learn More:

“About Refugee Tales.” Refugee Tales, Gatwick Detainees Welfare Group, refugeetales.org/about-refugee-tales/.

Brockbank, Hannah. “Refugee Tales.” THRESHOLDS, University of Chicester, thresholds.chi.ac.uk/refugee-tales/.

Cleave, Chris. “World Refugee Day: The Lorry Driver’s Tale, as Told to Chris Cleave.”The Irish Times, The Irish Times, 20 June 2016, www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/world-refugee-day-the-lorry-driver-s-tale-as-told-to-chris-cleave-1.2691968.

Herd, David. “Modern Day Canterbury Tales Refreshes Chaucer to Tell the Lost Stories of Refugees.” The Conversation, The Conversation US, Inc, 16 June 2015, theconversation.com/modern-day-canterbury-tales-refreshes-chaucer-to-tell-the-lost-stories-of-refugees-42981.

The Refugee Tales Website: http://refugeetales.org