This year marks the 10th anniversary of the University of Notre Dame‘s Medieval Institute‘s Medieval Studies Research Blog—a benchmark and milestone—which warrants both celebration and reflection on the evolution of the project, especially certain important actors and pivotal moments that have shaped the academic blog into an accessible resource for so many scholars and medievalist as well as general and public audiences.

The project was conceived by Dr. Kathryn Kerby-Fulton, now an Professor Emerita of English and Medieval Studies at the University of Notre Dame, specializing in the study of Middle English manuscript studies. Kerby-Fulton intuited that an academic blog could become an asset to the medieval institute, and so she brought together a team of graduate students to whom she pitched her academic blog project. Kerby-Fulton, in her wisdom and generosity, leaned on the next generation of scholars to get her project off the ground. Although she was the founder, the project, then called the Chequered Board, has always endeavored to support and lift up students and junior scholars. She envisioned the academic blog as both a forum for public medievalism, a space for academics engaging directly with general readers and a public audience, but also as a serious online, open-access resource for specialists in the field.

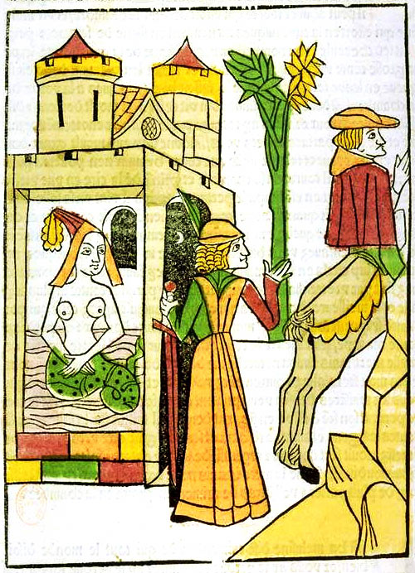

Many of the earliest blogs in fact, came from assignments in her graduate classes, asking students to reflect and analyze aspects of Middle English manuscripts and their intricacies and peculiarities. Dr. Kerby-Fulton had long recognized certain parallels between modern websites and medieval manuscripts, characteristics that print culture often passed by, including marginalia and visual formatting, as well as their respective function as multimedia objects, especially the interplay between aesthetic (whether illustrations or illuminations) and textual elements in both websites and manuscripts. Just as websites frequently feature a combination of texts, images and paratexts, so too do medieval manuscripts, and this affinity is at the heart of Kerby-Fulton’s vision for the project.

Indeed, my first-ever blog “Bobbing for Answer” discusses the Bob and Wheel in the manuscript containing Gawain and the Green Knight, and builds on Kerby-Fulton’s own work in her foundational text, Opening Up Medieval Manuscripts. My blog explores possible ways in which this poetic feature could offer semantic options and performative opportunities for readers of the poem in its manuscript context. These graduate student blogs, however, were just the beginning of the project.

Dr. Kerby-Fulton then organized a team of medievalist graduate students to conceive of possible directions and special series, as well as to help her run the blog project (then known as the Chequered Board). From project’s inception, she encouraged students take the reins and shape what would become the University of Notre Dame’s Medieval Institute’s Medieval Studies Research Blog into the active resource that it is today, open to academics of all levels from graduate students to senior scholars.

In order for the project to run efficiently, a blog manager was selected from the team, Dr. Nicole Eddy, who had previously worked for the British Library and had headed up their medieval manuscript blog, so she was familiar with the online genre and brought a wealth of knowledge and experience to the project. After her foundational role in establishing the blog and getting the project off the ground, blog management passed to Dr. Andrew Klein who continued the work. Once Dr. Klein left for his current position, the role of blog manager was handed off to Dr. Karrie Fuller. It was around this time that the project shifted from Dr. Kerby-Fulton’s personal research initiative to a project funded and overseen by the University of Notre Dame’s Medieval Institute, which came with rebranding and the new name for the project, the Medieval Studies Research Blog, which remains its title today.

All projects need funding and institutional support to survive, and without the steadfast championing of the Medieval Studies Research Blog by Dr. Kerby-Fulton and both the Medieval Institute Director, Dr. Thomas Burman, and the Associate Director of the Medieval Institute (and fellow contributor), Dr. Megan Hall, our beloved Medieval Studies Research Blog may not have endured. Instead, it thrived and continued evolving into the valuable open access online academic resource it is today.

After a few years of managing the blog, Dr. Fuller passed the role to me, and it was at long last my turn to take the helm of the project Although I had been a contributor and partner throughout the entirety of the project, I have served as blog manager has for the past five years, in which we’ve seen the project continue to expand and transform to meet the diverse and ever-changing needs of the field.

At the Medieval Studies Research Blog, we are blessed to have our regular contributors (currently including Dr. Linnet Heald, Dr. Nick Kamas, and Dr. Charles Yost, all graduates of the Medieval Institute) in addition to guest and alumni contributors. The work of many junior scholars affiliated with the Medieval Institute at the University of Notre Dame has fostered the growth of our project, which has since received attention from departments of education, scholars, enthusiasts, fellow bloggers and even the occasional author of fiction.

I would like also to cast a spotlight on some of the projects and special series, which in addition to the many excellent blog posts featured on the Medieval Studies Research Blog, have helped shape the project. Some of these projects include: The Medieval Poetry Project and A Scientific Analysis of the Pearl-Gawain Manuscript. New projects are rolling out in force this year, such as the Medieval Homily Project and Medieval Fable Project, while older special series, such as Working in the Archives, continue to prove a resource for young scholars in the field. And now, the MSRB now also features transcripts and reflections on its sister-project, the Meeting in the Middle Ages podcast spearheaded by William Beattie and Ben Pykare. Having a somewhat unique perspective—a kind of bird’s eye view—serving in various roles at the Medieval Studies Research Blog, I’ve had the privilege of advancing the project and watching as it has continued to gain traction and momentum in the field, and I am so excited to see where the next ten years take us, and what is in store for the MSRB.

Most of all, on this 10th anniversary of the Medieval Studies Research Blog, we at Notre Dame’s Medieval Institute want to thank you—our readers—for being so interested and invested in this public medievalism project, and for helping us sustain our viewership. Here’s to another successful year and continued growth and expansion of the Medieval Studies Research Blog.

Stay tuned for a forthcoming Meeting in the Middle Ages podcast interviewing the four blog managers of the Medieval Studies Research Blog, coming this spring!

Richard Fahey, Ph.D.

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame