King Richard II would not be considered a widely popular king. Coming to power in 1377 when he was ten years old, advised by councils though influenced most notably by his uncle John of Gaunt with whom he later had a falling out, the king’s power and ability to rule remained suspect throughout his reign. What power he did wield was often put to the test by such events as the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, the threat of plague, and political upheaval, all of which led to frequent characterizations as a boy hampered by his youth and unfit to rule effectively.[1] Medieval depictions and illustrations of the king demonstrate how many people after his reign may have seen him: young, naïve, unmanly, and stupid. And after Richard II was eventually deposed in 1399 when he was 32 years old, a certain amount of relish and schadenfreude seeped into illustrated post facto portrayals of the king.

A quick survey of these depictions reflects the king’s public image as it was held after his deposition. Images of a young Richard II characterized him in keeping with the knowledge of the coming debacles that England was to experience during his reign.

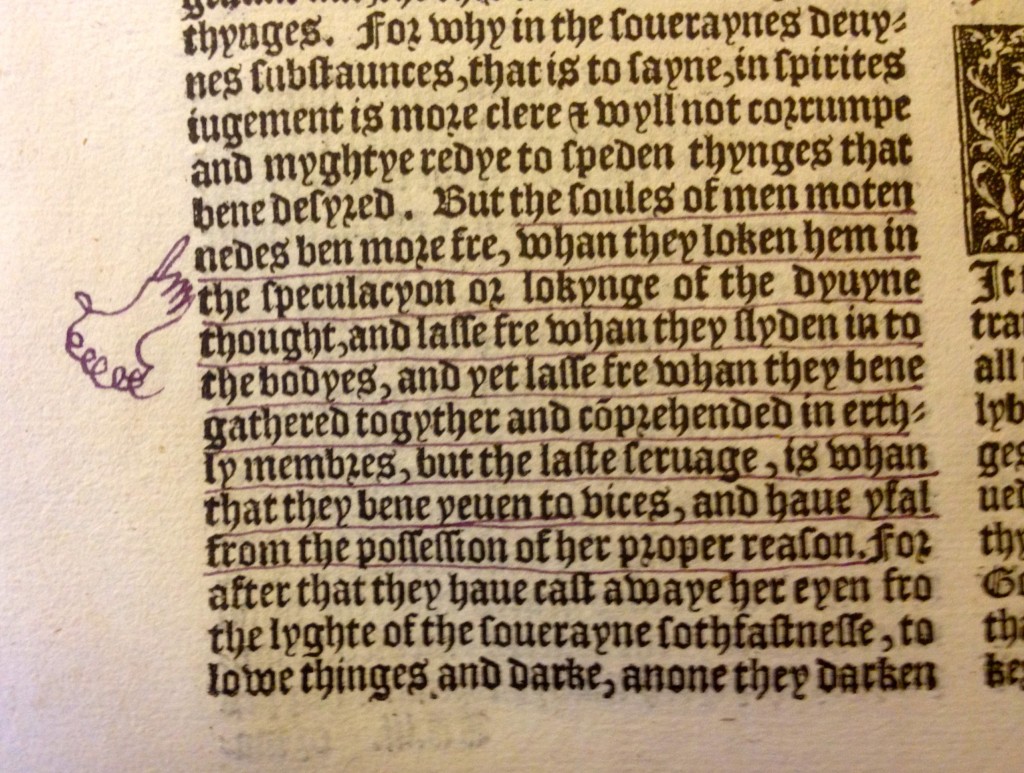

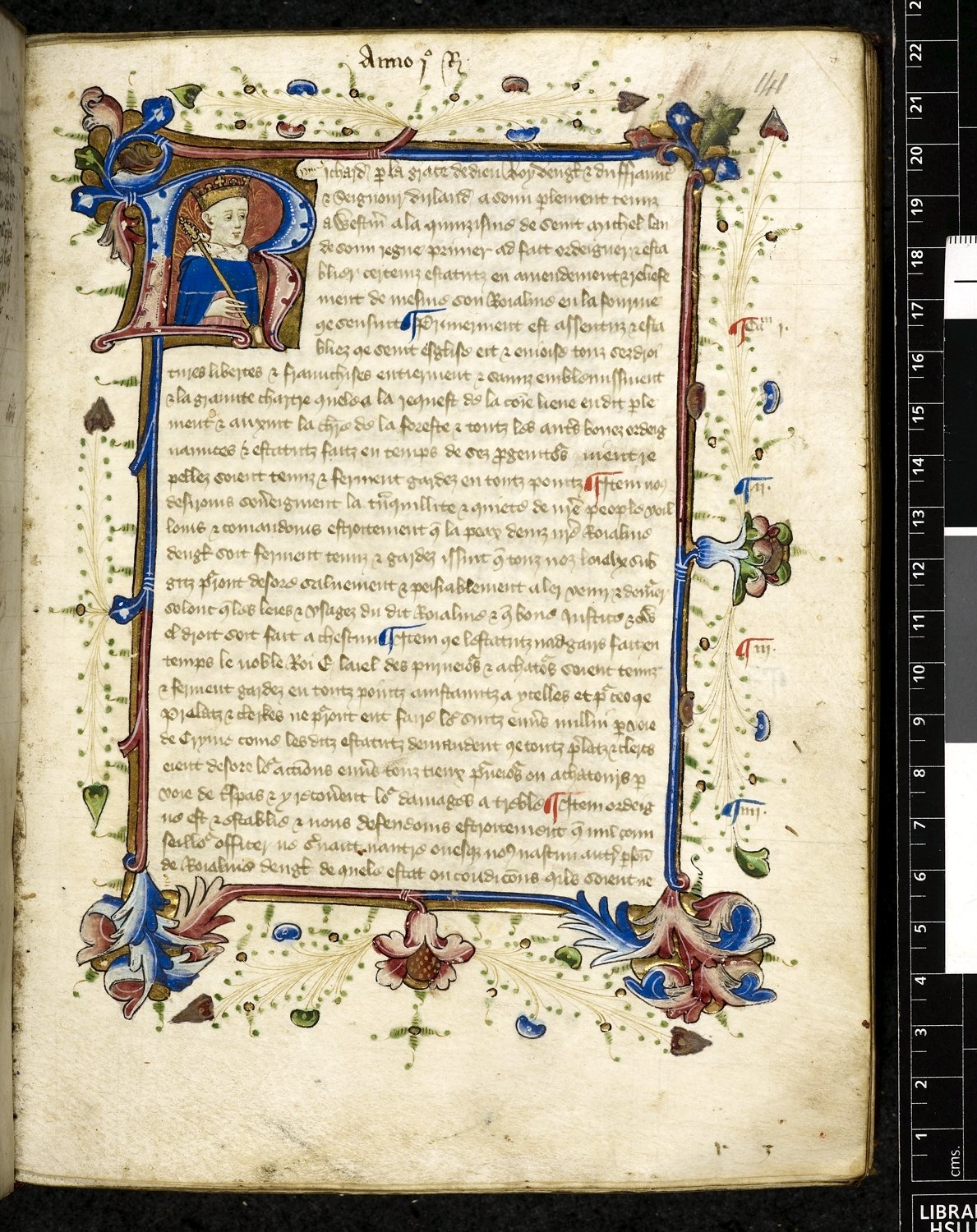

Seen here, the king peers over his own statutes with droopy, disinterested eyes, perhaps with a hint of uncertainty. A large forehead, exaggerated ears, a sallow face, and a weak chin each underlines the not-so-subtle caveat to these statutes: take them with a grain of salt, and proceed with caution.

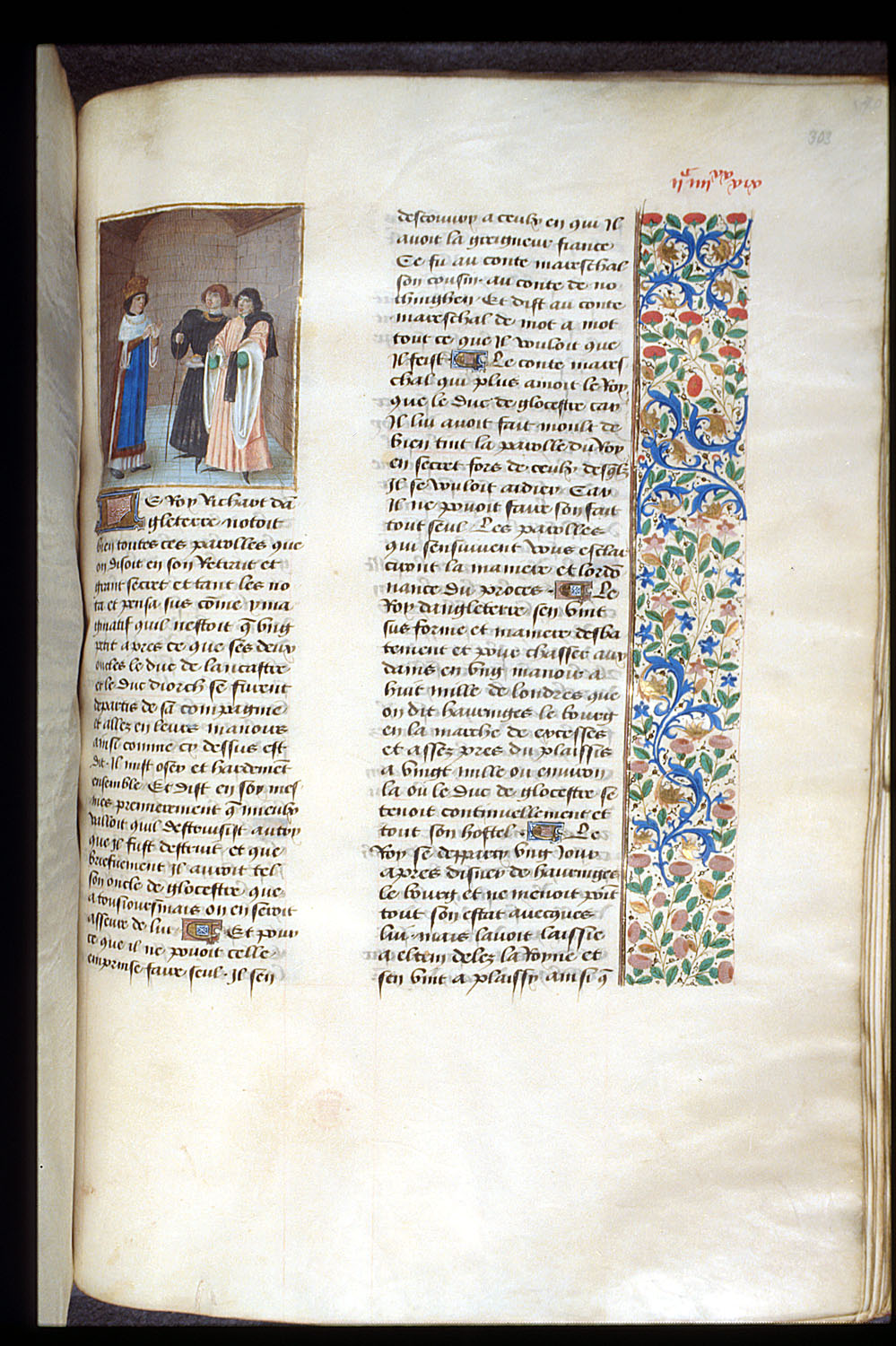

The second image portrays the young king banishing two earls, and we observe his features – a round face, slight frame, dull eyes – set against the prominent features of the earls, seen here to have more pronounced jawlines and chins. Though the eyes of the court are fixed on the king, the faces register blank expressions; the scribes, on the other hand, look dreadfully miserable.

Such characterizations carry over to scenes of the king in action as well.

As Richard knights Henry of Monmouth of Ireland, the king’s regal attire and armor dwarf his frame, his protruding lips frown, and though the new knight leans respectfully over his horse, the horse itself glares obstinately at Richard’s horse, who has adopted a pose of weakness or subservience with eyes closed and knee bowed.

We see the king’s slight frame again when he instructs an earl and another man, two figures who side with one another, one firmly clutching a staff between them and the king, and the other with hands raised in a possible protest or confrontation.

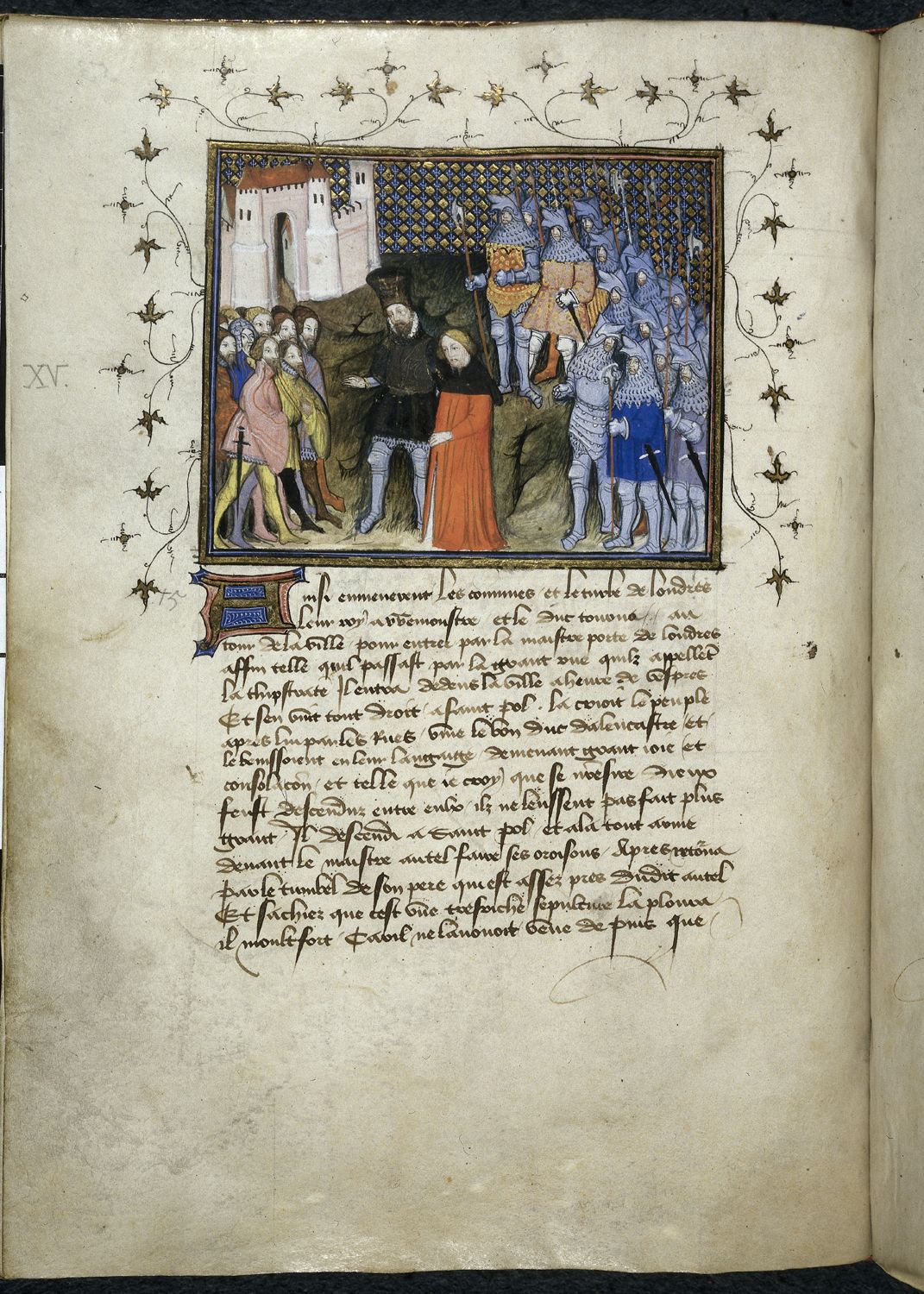

The next three images depict Richard II in disguise and captivity, his power wrenched away from him.

In each scene here, the king’s head is hanging low, bowed down and resigned to the fate that had befallen him. Though every illustration in this post date after Richard II’s deposition, these last three portrayals of the king carry a hint of gravitas to color these images. Although the king’s poor reputation held a long legacy, the images of his fall from the throne perhaps indicate that, regardless of his disastrous reign, public opinion of what befell him took into account his misfortune with at least a small amount of empathy–not as a king but as another mere mortal, subject to the same bad strokes of chance or fate as those he ruled, incompetence and all.

[1] Christopher Fletcher. Richard II: Manhood, Youth, and Politics 1377-99. (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2008), 2.

Jacob Schepers

PhD Candidate

Department of English

University of Notre Dame