Many readers may not be familiar with the figure of Asenath, though she made her debut for modern audiences in DreamWorks Animation’s film Joseph: King of Dreams (released in 2000 as the prequel to The Prince of Egypt (1998)).

She is mentioned just three times in the Book of Genesis as the “daughter of Potiphera, priest of On” whom Pharaoh gave to Joseph as a wife (41:45). Before the seven years of famine came to Egypt, as predicted by Joseph, she bore two sons (41:50) who are named Manasseh and Ephraim (46:20). Asenath is thus remembered as occupying an important place in the genealogy of Israel.

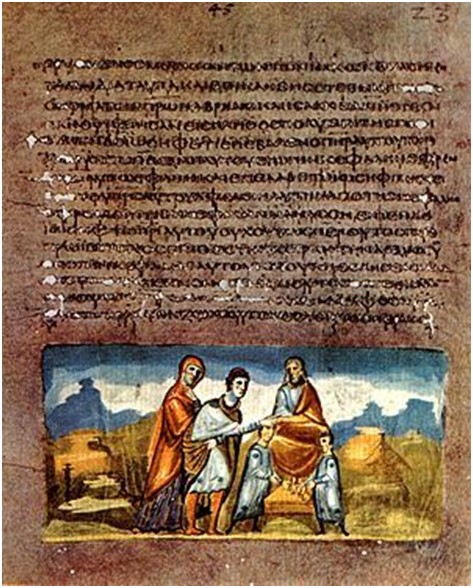

Despite scant mention of her in the biblical text, however, she had quite a life outside of it. Judaic commentators were driven to explain how Jacob’s lineage could rightfully be passed through a non-Hebrew woman, and the first attempt made was among the Jewish Diaspora in Egypt, probably in Alexandria, around the time of Trajan’s rule (98-117 A.D.) (Burchard 104). Written in Greek, some scholars have placed the text among the Pseudepigrapha (though the work does not purport to have been written by anyone in particular); while others view it as an example of Midrashic tradition (Dwyer 118); and still others consider it to be a Hellenistic romance (Pervo 175; Heiserman 184-186). From the multi-cultural hub of Alexandria, the text passed through Christian hands into a myriad of Near-Eastern and European languages (Peck 2). It was quickly subsumed into Byzantine hagiography (Dwyer 118). And in the twelfth century, it was translated twice into Latin, once possibly at Canterbury, and it was this version that became the basis of a Middle English translation (Reid, “Female Initiation” 138).

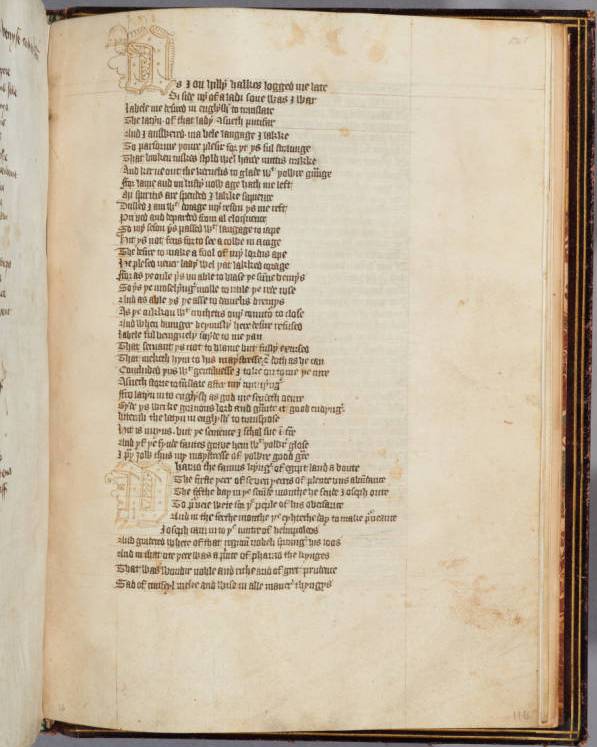

The Storie of Asneth was translated into Middle English sometime during the first half of the fifteenth century in a West Midlands dialect (Peck 3). The only surviving copy we have of the text, though, is preserved in Huntington Library, MS Ellesmere 26. A. 13., copied sometime around 1450 or 1460 (Peck 9). The text can be found on ff. 116r-127r.

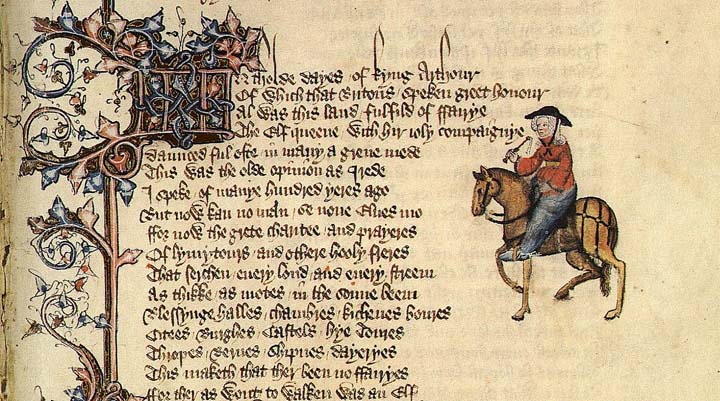

The manuscript can be divided into three parts. The first (ff. i r-v v) is in the hand of John Shirley (c. 1366-1456), book dealer and scribe famous for his copies of Chaucer, Lydgate, Hoccleve, and Trevisa. His section contains some devotional verse and poetry by Lydgate, a few lines of Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde with some additions from Petrarch, and some lines from John Walton’s translation of Boethius’s De consolatione Philosophiae. The second part (ff. 1r-115v) of the manuscript is in a different hand and includes a few more short poems by Lydgate but mainly consists of Hoccleve’s Regement of Princes. The third part is taken up by The Storie of Asneth, written in yet another hand (Hume 55). By all accounts, the manuscript appears to be a composite, but just when the three parts were bound together is difficult to ascertain.

The entire digitized manuscript may be viewed here.

For more information, see the Digital Scriptorium Catalog Entry.

What is most interesting is that on the verso side of f. v, Shirley fashioned a bookplate that displays the names of sisters Margaret and Beatrice Lynne as well as his own. Shirley married Margaret at some point between 1421 and 1441, so it has been posited that he gave the first section of the manuscript to the sisters as a gift (Peck 2-3). In the second part of the manuscript, there is also a reference (f. 115r) to “Aluredo Corneburgh de Camera Regis,” written, it would appear, in Shirley’s hand. Avery Cornburgh was a Yeoman of the Chamber to King Edward IV and was wed to Beatrice sometime between 1459 and 1467, likely bringing into this arrangement section two of the manuscript. Shirley and Cornburgh seem to have known one another and eventually joined themselves to the same family. It makes commensurate sense, then, that the first two parts were bound together, and it is quite possible that at this time, the third section was added, though this cannot be verified (Hume 55-56).

Huntington Library, MS Ellesmere 26. A. 13. has, then, a strong connection to two literate, book-owning women, and in fact, another name appears in the margins (f. iii v)—“Elizabeth Gaynesford,” a friend of Beatrice. Thus, the book may even have circulated among a close-knit group of female readers. The circumstances surrounding the production of the Middle English Storie of Asneth are no less interesting. In her article “Patroness of Orthodoxy: Elizabeth Berkeley, John Walton, and the Middle English Storie of Asneth, a West Midlands Devotional Text,” Heather Reid has mounted considerable evidence that points to Elizabeth Beauchamp (née Berkeley), Countess of Warwick (1386-1422) as patroness of the Middle English text, having engaged her cleric, John Walton, an Augustinian canon at Osney Abbey, as translator. We can observe a decidedly female interest in vernacular translation of this text on the other side of the Channel as well. Vincent of Beauvais included an abbreviated version of Asenath’s story in his Speculum historiale (1253), and in 1332, Jeanne de Bourgogne, wife of Philippe VI de Valois (r. 1328-1350), commissioned Jean de Vignay to translate this text into French, producing the Miroir historial (Lusignan 497-498). So what made the account of Asenath so attractive to female readers?

First of all, the narrative tells how Asenath comes to love Joseph. Born the beautiful daughter of the priest of Heliopolis, a powerful position, she is haughty and refuses all suitors. When asked by her parents if she would marry Joseph, Pharaoh’s right-hand man, who will just so happen to be paying them a visit, she balks at the idea. But when she watches him approach from her tower, she begins to feel the pangs of lovesickness. To add to the intrigue, though, Joseph spurns her, rejecting any woman who does not worship his God. Asenath is distraught and locks herself in her room, fasting and donning the sackcloth and ashes of repentance amidst her wails of lamentation. Eventually, she throws the household idols and all religious paraphernalia out the window. And after a significant period of such penance, she stands one night at her window and prays to the Hebrew God, converting, as it were, to Judaism. She is then graced with a mystical experience as a beautiful man appears to come down from Heaven, “a prince of Godis hous, and of Hys hevenly ost” (l. 420). He tells her to clean herself and change her clothes, for she will marry Joseph. Dressed afresh, Asenath demonstrates her hospitality by offering to get him some bread and wine from the cellar. He asks instead that she bring him a honeycomb, and she is upset because she knows there is none. He tells her to go check nonetheless, and lo, a honeycomb is present. Together, they share the honeycomb, about which she is told that

[…] blessed be thei that come to God in holy penance,

For thei schul ete of this comb, that bees made of Paradise,

Of the dew of rosis there, that are of gret plesance.

The angelis of God schul ete also this comb of prise,

And who that eteth of the same schal never dye in no wise. (ll. 545-549)

As soon as the “man com doun fro hevene” (l. 415) departs, Joseph returns to the house. He has received knowledge in a dream that Asenath is to be his wife, and the very next day Pharaoh marries them. We are then told: “And after Joseph knewe his wyf and sche conceived sone, / And bar Manasses and Effraim – this was here procreacion” (ll. 682-683). The remainder of the story deals with a threat upon Joseph’s life and a dramatic combat.

The full text is available here.

The text reads like a romance—ever a much-loved genre—but it is also biblically based and hagiographical in tenor. The Storie of Asneth shares similarities with accounts of heroic Old Testament women, like those found in the books of Ruth, Esther, Tobit, and Judith (West 76). And as Susan Bell notes, “Throughout the Middle Ages, following the teachings of the early Christian fathers, women were exhorted to model themselves on biblical heroines” (158). In one sense, the text could have been conceived of as an exemplum, demonstrating the “ethical virtues” of “self-discipline, penitence, humility” (Kee, “The Socio-Religious Setting” 185). Such a didactic yet romantically appealing narrative could have served well for instruction within a household (Peck 4-5). In the first section of her article “The Storie of Asneth: A Fifteenth-Century Commission and the Mystery of Its Epilogue,” Cathy Hume also demonstrates that the Middle English Storie of Asneth reflects fifteenth-century trends in hagiography and textual consumption, particularly by women, and she argues that what made the text so well received is that it presents an exemplary account of pious married life. The text shows that women can be religious and married, not forced to choose between the two, something that we know real women struggled with, like Margery Kempe. This makes figures like Asenath more imitable, a subject upon which Catherine Sanok has also had much to say. In an earlier article (“Female Initiation Rites and Women Visionaries: Mystical Marriage in the Middle English Translation of The Storie of Asneth”), Heather Reid discusses the text also in relation to accounts of women visionaries and writes a great deal about Asenath with respect to sacred marriage, chastity, and mysticism—all important topics also for this time period, as Dyan Elliott likewise attests. However, Asenath’s actual marriage to Joseph is also quite intriguing.

Asenath is an admirable young woman but so too is her relationship with Joseph, though little has been said about the spirituality of her human marriage. However, for the majority of the female lay readership of Asenath’s story, this would have been the subject of more immediacy. When Joseph comes to see Asenath after her conversion—both having received a vision from God—he “[…] streihte out his hand, and loveli gan her brace. / Thei kiste then bothe in same with cuntenance excellent” (ll. 621-622). Asenath welcomes him, as she did before, yet this time she moves to wash his feet, a gesture reminiscent of Christ towards his disciples. She tells Joseph, “I schal hem wasshe […] / Thi feet ar myn owne feet, thi handdis also with alle, / And thi soule ys my soule: thu are thn myn owen fere” (ll. 627, 630-631). While she exhibits humility towards Joseph by washing his feet, she also declares their relationship to be reciprocal: he is hers as much as she is now his. For all intents and purposes, she describes the two of them to be the biblical “duo in carne una” (Mark 10:8). This paints a rather encouraging picture of human love and marriage; indeed, it is the prelapsarian ideal in its parity. For a fifteenth-century female audience engaging with this text, this is not only enlightening and inspirational; it is also empowering. The union Asenath is establishing with Joseph is Edenic in quality, and this is something for which Joseph also seems to strive. Both are represented as exceptional human beings who achieve an extraordinary relationship, and their union is one in which God is the center. In fact, their marriage is brought about through God, once Asenath—who possesses a noteworthy degree of control over her own destiny—decides to dedicate herself to “the heyhe Lord God of Joseph, almyhti in His throne” (l. 349). And the bond produced from such a relationship is one of equal affection and regard, of selflessness and charity. The presentation of marriage in The Storie of Asneth is one in which both parties are able to honor God through their relationship with one another, a union not only approved of, but promoted by God—something that would have resonated well.

On so many counts, The Storie of Asneth would have been a captivating text for a fifteenth-century female readership. Women were in no way ignorant of the fact that they endured the insidious yoke of patriarchy in both temporal and spiritual spheres, even though Judeo-Christian theology is very clear that women’s souls are equal. It is no surprise, for instance, that Catherine of Alexandria was such a popular saint, as discussed in a blog post by Mary Helen Galluch. Asenath is less radical than Catherine, though, in her devotion. And she weds and continues the family line, marrying, as it were, piety and the lay life—much as many medieval women did.

But her example lends a dignity to the lay life, and there are a number of parallels between Asenath’s actions in the text and those of the righteous woman of Proverbs 31. While on the one hand, Asenath remains circumscribed by patriarchal society (as the woman of Proverbs 31 is also) and can be seen as something of a safe, contained model; on the other hand, her claim to be Joseph’s peer in marriage and her exemplary conduct as a human being (regardless of gendered expectations) bring her far above the level of vessel and drudge. She is not a beautiful but passive romance heroine, for she energetically shows physical charm to be of far less importance than virtuous actions and that “a woman who fears the Lord is to be praised” (Proverbs 31:30).

Hannah Zdansky, Ph.D.

University of Notre Dame

Bibliography (Cited and/or Suggested):

Primary Sources

“The Storie of Asneth.” Heroic Women from the Old Testament in Middle English Verse. Ed. Russell A. Peck. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, 1991. 1-23.

Secondary Sources

Bell, Susan Groag. “Medieval Women Book Owners: Arbiters of Lay Piety and Ambassadors of Culture.” Women and Power in the Middle Ages. Ed. Mary Erler and Maryanne Kowaleski. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1988. 149-187.

Burchard, Christoph. “The Importance of Joseph and Aseneth for the Study of the New Testament: A General Survey and a Fresh Look at the Lord’s Supper.” New Testament Studies 33 (1987): 102-134.

Douglas, Rees Conrad. “Liminality and Conversion in Joseph and Aseneth.” Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 3 (1988): 31-42.

Dwyer, R. A. “Asenath of Egypt in Middle English.” Medium Aevum 39 (1970): 118-122.

Elliott, Dyan. Spiritual Marriage: Sexual Abstinence in Medieval Wedlock. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

Hartman, Geoffrey. “Midrash as Law and Literature.” The Geoffrey Hartman Reader. New York: Fordham University Press, 2004. 205-222.

Heiserman, Arthur R. The Novel before the Novel: Essays and Discussions about the Beginnings of Prose Fiction in the West. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1977.

Hume, Cathy. “The Storie of Asneth: A Fifteenth-Century Commission and the Mystery of Its Epilogue.” Medium Aevum 82 (2013): 44-65.

Kee, Howard C. “The Socio-Cultural Setting of Joseph and Aseneth.” New Testament Studies 29 (1983): 394-413.

Kee, Howard C. “The Socio-Religious Setting and Aims of ‘Joseph and Asenath.’” Society of Biblical Literature 1976 Seminar Papers. Ed. George MacRae. Missoula: Scholars Press, 1976. 183-192.

Kraemer, Ross Shepard When Aseneth Met Joseph: A Late Antique Tale of the Biblical Patriarch and His Egyptian Wife, Reconsidered. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Lipsett, B. Diane. “Aseneth and the Sublime Turn.” Desiring Conversion: Hermas, Thecla, Aseneth. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011. 86-122.

Liptzin, Sol. “Lady Asenath.” Biblical Themes in World Literature. Hoboken: KTAV Publishing House, Inc., 1985. 62-73.

Lusignan, Serge. « Le temps de l’homme au temps de monseigneur saint Louis : le Speculum historiale et les Grandes Chroniques de France ». Vincent de Beauvais : Intentions et réceptions d’une œuvre encyclopédique au Moyen-Âge. Ville Saint-Laurent, Québec : Les Éditions Bellarmin, 1990. 495-505.

Nisse, Ruth. “‘Your Name Will No Longer Be Aseneth’: Apocrypha, Anti-Martyrdom, and Jewish Conversion in Thirteenth-Century England.” Speculum 81 (2006): 734-753.

Peck, Russell A. Introduction. “The Storie of Asneth.” Heroic Women from the Old Testament in Middle English Verse. Ed. Russell A. Peck. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, 1991. 1-15.

Pervo, Richard I. “Joseph and Asenath and the Greek Novel.” Society of Biblical Literature 1976 Seminar Papers. Ed. George MacRae. Missoula: Scholars Press, 1976. 171-181.

Reid, Heather A. “Female Initiation Rites and Women Visionaries: Mystical Marriage in the Middle English Translation of The Storie of Asneth.” Women and the Divine in Literature before 1700: Essays in Memory of Margot Louis. Ed. Kathryn Kerby-Fulton. Victoria, British Columbia: ELS Editions, 2009. 137-152.

Reid, Heather A. “Patroness of Orthodoxy: Elizabeth Berkeley, John Walton, and the Middle English Storie of Asneth, a West Midlands Devotional Text.” Devotional Culture in Late Medieval England and Europe: Diverse Imaginations of Christ’s Life. Ed. Stephen Kelly and Ryan Perry. Turnhout: Brepols, 2014. 405-441.

Sanok, Catherine. Her Life Historical: Exemplarity and Female Saints’ Lives in Late Medieval England. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007.

Vikan, Gary. “Illustrated Manuscripts of the Romance of Joseph and Aseneth.” Society of Biblical Literature 1976 Seminar Papers. Ed. George MacRae. Missoula: Scholars Press, 1976. 193-208.

West, S. “Joseph and Asenath: A Neglected Greek Romance.” The Classical Quarterly 24 (1974): 70-81.