As a medievalist studying at the University of Notre Dame, I am afforded many luxuries. The university’s resources for research in my field are exceptional, and I can honestly say that from my personal experience both the Medieval Institute and my home English Department have proven to be places where intellectual curiosity flourishes and where the spirit of generosity pervades. It has been a wonderful place to pursue my graduate studies, and of course the campus is absolutely beautiful, as the university’s collection of scenic images affirms. But when I decided to move off campus my second year, out of the gilded bubble surrounding the university and into the rust belt of South Bend, I met with some starkly different and rather unsettling imagery.

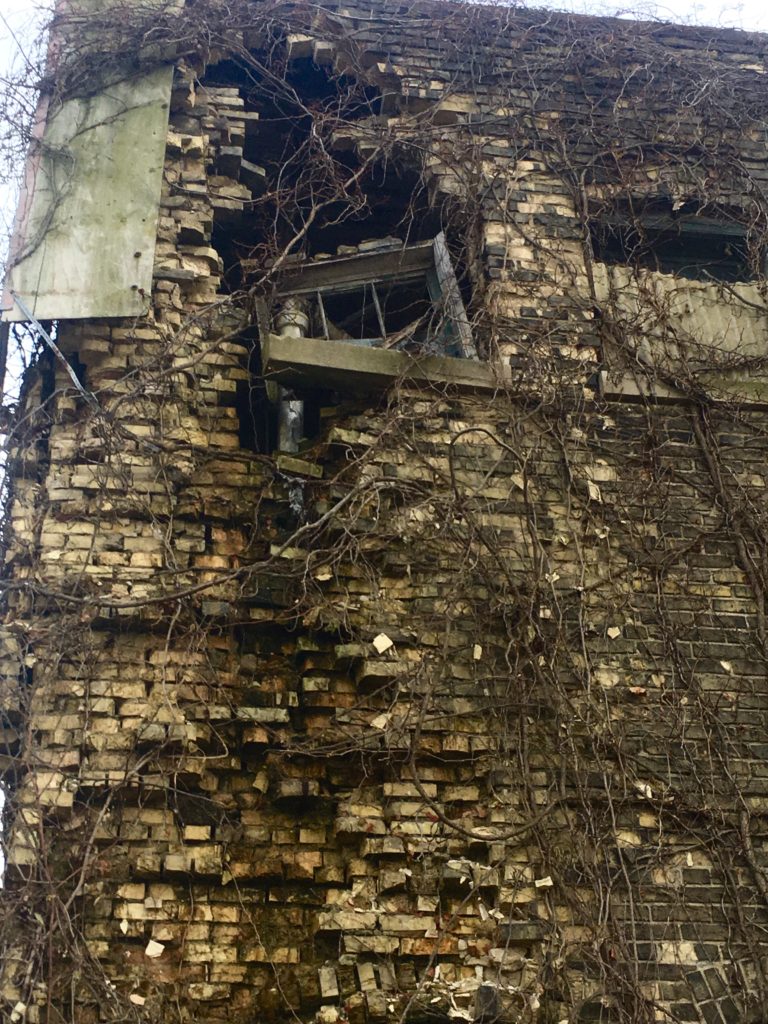

The juxtaposition between the two spheres which I came to inhabit—between the gorgeous Neo-Gothic architecture that adorns the picturesque campus and the industrial ruins scattered throughout the cityscape of South Bend—became repeatedly reinforced by my regular journey between these worlds on each morning commute and then again each night as I returned home. Every evening, I would leave the Golden Dome behind and drive by boarded up houses and businesses, like this one on Sample Street, which I routinely passed on my way home.

Below is a closer view from the front of the building. I pause on this particular structure, because it became engrained in my mind over time—the beautiful green decay and broken bricks—the state of disrepair. To me, this building came to represent the rust belt ruins of South Bend. My wife—artist and graduate of Massachusetts College of Art & Design, Rajuli (Khetarpal) Fahey—photographed the rotting building and describes experiencing an overwhelming stench of mildew and mold wafting from the broken windows upon approaching the structure.

In my opinion, there is a certain beauty in the haunting imagery of this broken down building, which recalls a time before the place fell into ruin while simultaneously emphasizing its current dilapidation. This theme is well known to Anglo-Saxonists, as the question of ubi sunt “where are (they now)?” pervades the so-called Old English elegies, which reflect on the transitory nature of human existence, noting the decay of great civilizations passed. As I read these medieval poems in the ivory tower of Hesburgh Library, I found myself thinking about South Bend and the many other rust belt cities across the country, weathered by similar economic decay. More than any other Old English elegy, the Exeter Book Ruin prompted me to meditate on the industrial remnants of a former time in South Bend.

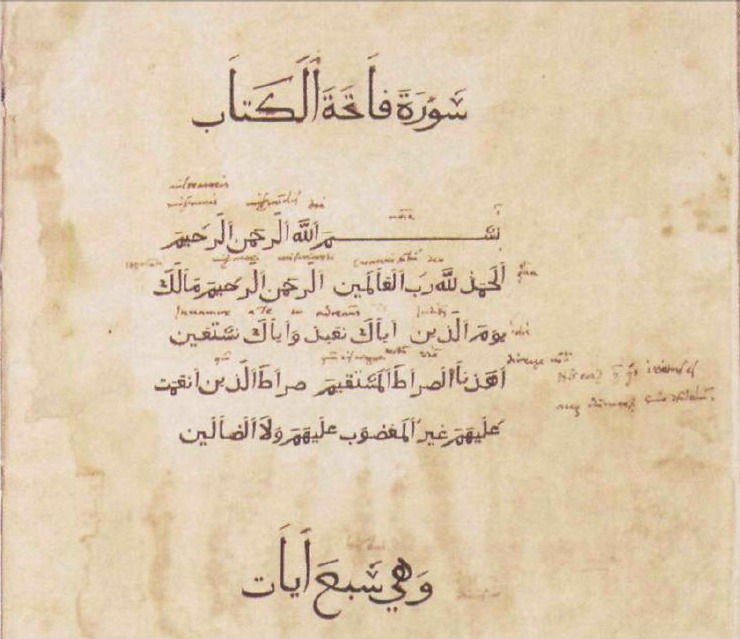

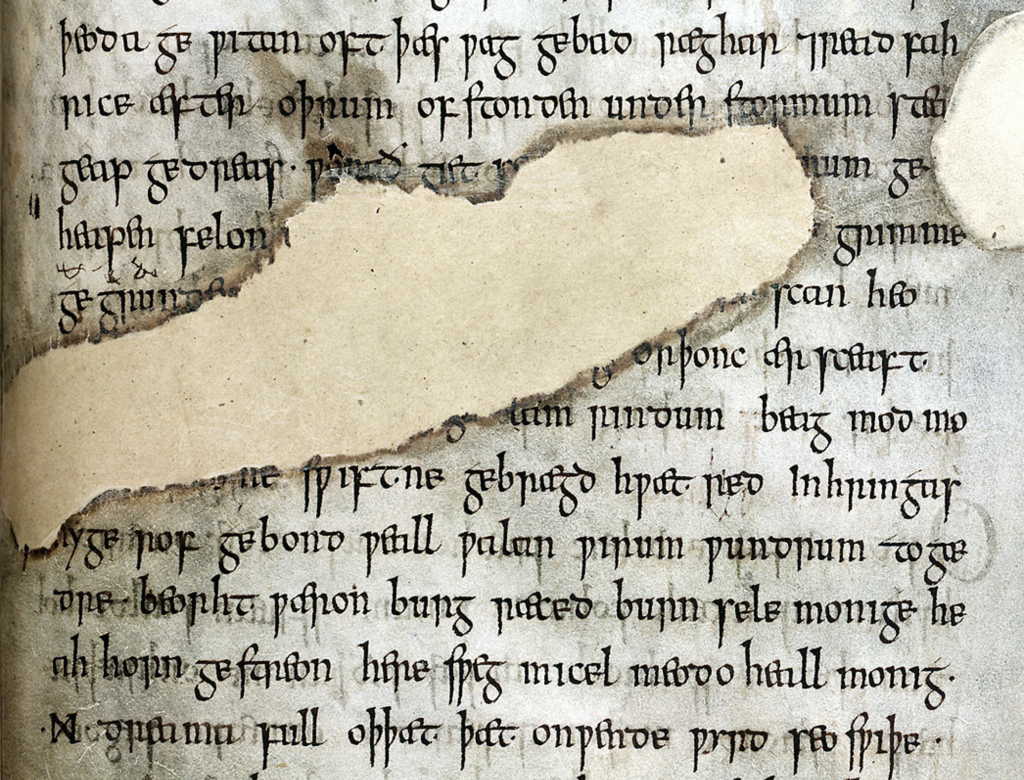

The Old English Ruin is itself a ruin—appearing on fire-damaged folia in the Exeter Book (Exeter Cathedral Library MS 3501). Fittingly, the poem bears its own marks from the wear of time and circumstance, and at first sounds almost like a riddle—beginning with one of the lexical markers scholars have used identify riddles (wrætlic meaning “wondrous” or “marvelous”). Moreover, in its manuscript context, the Old English Ruin is embedded within the two major collections of riddles found in the Exeter Book, amongst some stray riddles and the more enigmatic “elegies” in the codex, including The Wife’s Lament and The Husband’s Message. The Exeter Book Ruin demonstrates an interest in contemplating the destructive and the inevitable—crushing—passage of time, particularly on monumental manmade structures.

As Rajuli and I were discussing the poem and pockets of dilapidation throughout the city, she suggested that we drive around the city and take a family tour to document some of the ruins of South Bend, which I use here to complement sections of my translation of the Old English Ruin.

Wrætlic is þes wealstan wyrde gebræcon;

burgstede burston brosnað enta geweorc

Hrofas sind gehrorene hreorge torras,

hrungeat berofen (1-4).

“Wondrous are these wall-stones,

broken by fortune, the citadels crumbled,

the work of giants ruined.

The roofs are collapsed,

the towers tumbled, the pillars bereft.”

wurdon hyra wigsteal westen staþolas,

brosnade burgsteall (27-28).

“their fortification became deserted places,

their strongholds crumbled.”

Forþon þas hofu dreorgiað,

ond þæs teaforgeapa tigelum sceadeð

hrostbeages hrof (29-31).

“Therefore these houses have decayed,

and this gabbled structure sheds its tiles,

the roof of ringed-wood.”

Sadly, the descriptions of desolation and structural decay in the poem reflects a bit too closely the current state of disrepair which still plagues certain parts of South Bend. This deserted business located on Indiana Avenue, once both Red’s Appliance Repair Center and Southside Electric, still bears obsolete information etched on the brick wall, whispering to us from the past. Reminding us that things were not always as they are today, and begging for renewal. Nevertheless, the enduring dilapidation that decorates the city stands as a reminder of how South Bend, and places like it, became collateral damage—destroyed by the tides of economic fluctuation.

As the sign suggests, South Bend is a city on the rise, racing to catch up to 21st century, and doing quite well in this effort. During my tenure at the University of Notre Dame, I have seen the city of South Bend improve tenfold—drawing new and thriving businesses, expanding campus infrastructure, renovating depressed neighborhoods, and even beginning to cultivate and encourage artistic movements within the city. Many rust belt cities do not have the advantage of housing such a vibrant university community which generates innovation and economic growth, and those cities have far greater challenges to overcome. Both the campus and the city at large often seem as if they are one enormous construction site: demolishing, repairing and rebuilding. Still, amidst citywide growth and revitalization lies the skeletal ruins of the rust belt economy.

Richard Fahey

PhD Candidate

Department of English

University of Notre Dame

Text and translation of the Old English Ruin

Collection of images “Rust Belt Ruins of South Bend”