Prior to the twentieth century, Guy of Warwick ranked among the most popular heroes of the Anglophone world, even being placed at one point among the Nine Worthies. And it is not hard to imagine why, as there is something for everyone in his story, for he is shown to be a great warrior and a dragon-slayer who later becomes a pilgrim and, eventually, a hermit.

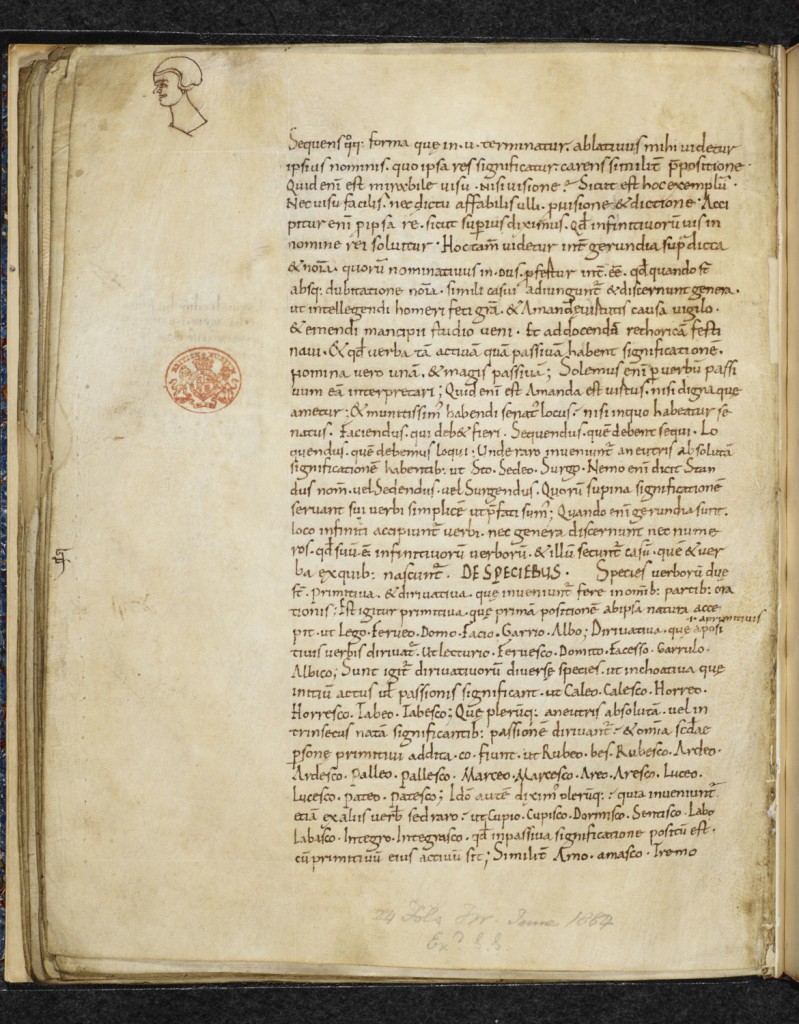

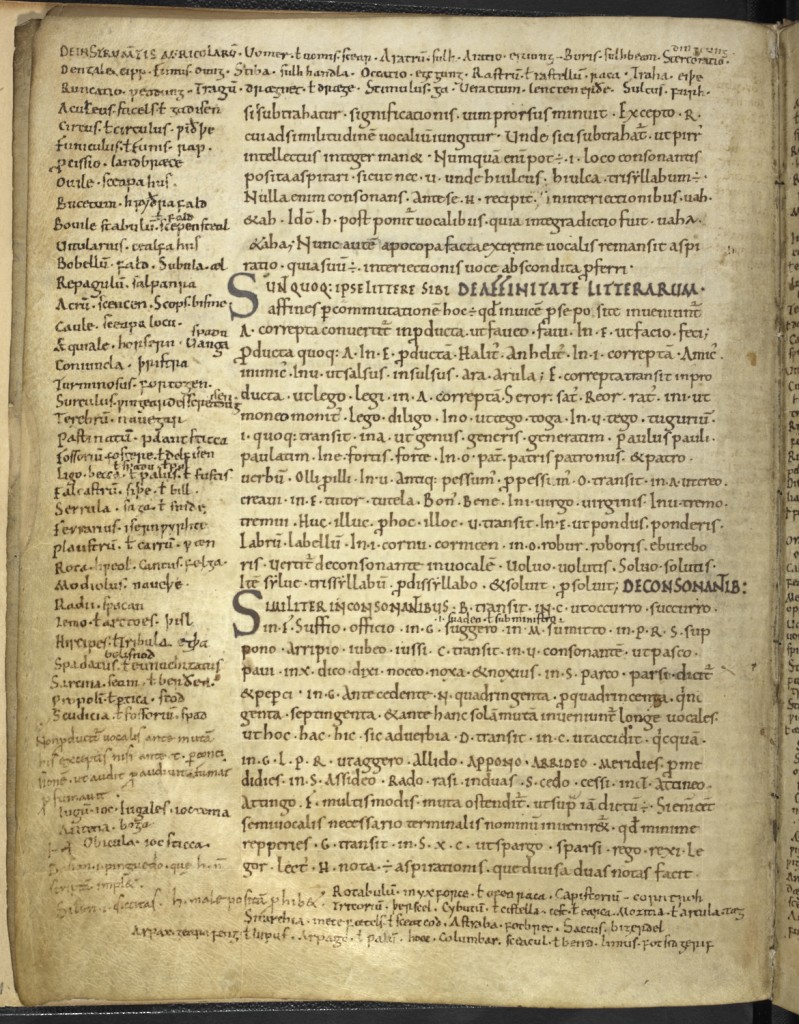

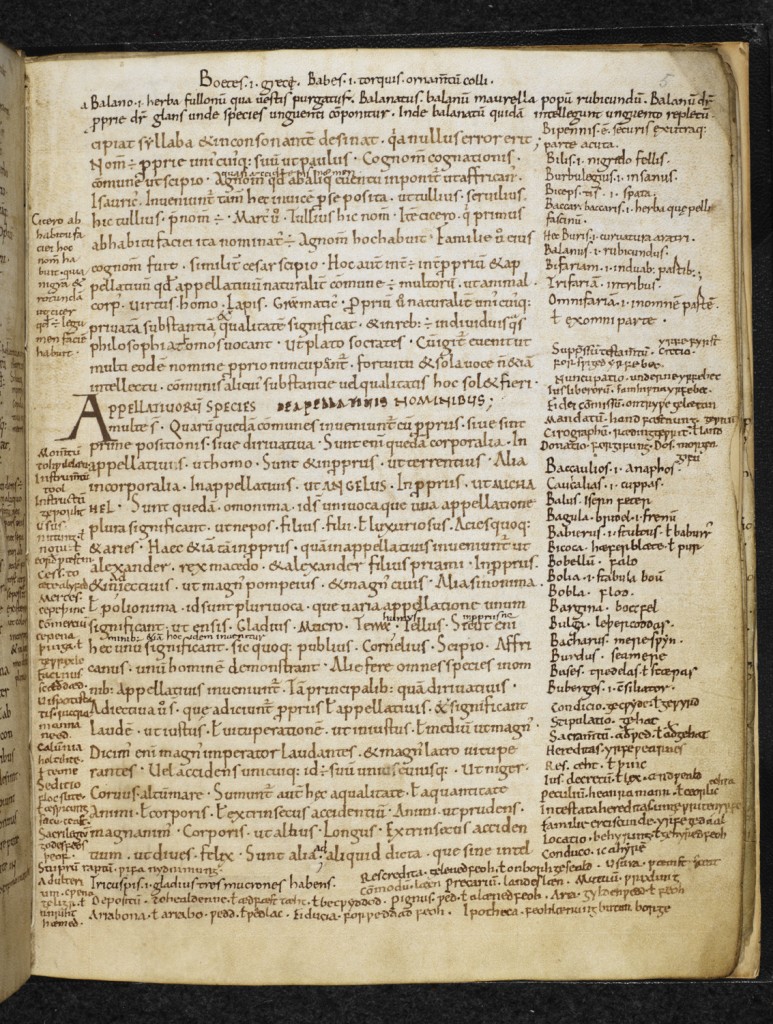

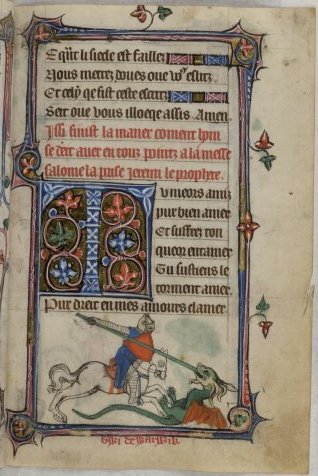

The narrative was first written in Anglo-Norman shortly before 1204 A.D. (Weiss, “Gui de Warewic” 7). Attesting to the lengthy story’s success, nine manuscripts and seven fragments survive in Anglo-Norman. The earliest complete copy that we have in Middle English can be found in the Auchinleck Manuscript, Edinburgh, National Library of Scotland, MS Advocates 19.2.1, dated to c. 1330-1340. Two other, much later versions exist in Cambridge, Gonville and Caius College, MS 107/176 (c. 1470s) and Cambridge, University Library, MS Ff.2.38 (c. 1479-1484) (Wiggins, “The Manuscripts and Texts” 64). And there are an additional two sets of fragments in Middle English. One thing interesting about the layout of the text in the Auchinleck Manuscript is that it is separated into a sort of trilogy, consisting of what is known as the couplet Guy of Warwick, covering Guy’s early exploits (ff. 108r-146v), the stanzaic Guy of Warwick, recounting his later life events (ff. 146v-167r), and Reinbroun, which deals with the feats of Guy’s son (ff. 167r-175v). The Auchinleck Manuscript also includes a text called the Speculum Gy de Warewyke, a homiletic treatise that uses Guy’s narrative as a frame to discuss the sins and the importance of contrition and penance.

The entire Auchinleck Manuscript, as well as a treasure trove of information, is available online here: https://auchinleck.nls.uk/.

Guy’s cultural importance extended beyond England and France and also into the early modern period. A now lost Middle English version likely served as the basis for the fifteenth-century Irish Beathadh Sir Gyi o Bharbhuic, copied in Dublin, Trinity College Library, MS 1298B, pp. 300-347. What is most remarkable about this version is that it incorporates material from the Speculum. It is furthermore no secret, for example, that Edmund Spenser’s Guyon from Book II of The Faerie Queene is modeled on Guy of Warwick, and we can also see reflections of Guy in the Redcrosse Knight of Book I (Cooper, “Romance after 1400” 718-719 and The English Romance in Time 92-99). In fact, as Helen Cooper demonstrates, the popularity of the Guy narrative continued unabated up through the Victorian era (“Romance after 1400” 704-706).

For more on the later life of the Guy of Warwick legend, see Dr. Siân Echard’s page: http://faculty.arts.ubc.ca/sechard/GUY.HTM.

So what, you might be asking, is this blockbuster story all about? Well, the narrative tells of Guy, a steward’s son, who falls in love with Felice, the Earl of Warwick’s daughter, and is compelled to climb the social ladder through heroic acts in order to prove himself. Guy has many battles and adventures on the Continent, winning fame and admiration abroad. While in Constantinople, he rescues a lion from a dragon. He also makes a bosom companion in the person of Terri of Worms. On his way back to England, Guy slays the villainous Otun, Duke of Pavia, but he also gets caught up in a confrontation in which he rashly kills the son of Count Florentine. Before returning home to Warwick, Guy helps King Athelstan by slaying a dragon that is ravaging Northumberland. He then marries Felice and fathers a child, Reinbroun. The trajectory is not unlike other romans d’aventure. But once he has fulfilled all of his desires, Guy is suddenly overcome by deep inner turmoil while gazing at the stars one evening, realizing that, as yet, God has had no place in his life. With this, he vows to dedicate himself to holy pursuits and become a pilgrim, expiating by means of his body, as he says, those sins committed by his body, namely the lives of others destroyed and lost through his reckless longing for glory. Upon departing, he gives Felice his sword, and Felice, in turn, gives him a ring to remember her by. (They halve the ring in later versions.) Their parting is a tearful one. In his subsequent travels, Guy, always incognito, makes his way to the Holy Land, aiding and rescuing others, Christian and “Saracen” alike, in many martial exploits. He assists the Saracen King Triamour by vanquishing the giant Amoraunt and, in the process, helps the Christian Earl Jonas and his sons. He also eventually saves his friend Terri by defeating Berard, the likewise treacherous nephew of Otun. Though comparatively little space is given to Felice, she devotes herself to serving her community in Warwickshire through charitable deeds. When Guy makes his final return to England, he aids King Athelstan again, this time preventing a Danish invasion by defeating the giant Colbrond and thus becoming the savior of England. However, he retreats unnoticed to the woods outside of his estate in Warwick. Guy’s desire is to receive religious instruction from another hermit and to live out the rest of his days in contemplation. Guy eventually learns from the Archangel Michael that he has a week left to live (he will die on the eighth day), and so he sends word to Felice as well as his ring (or half-ring) for identification purposes. She comes to him on the point of death, and his soul is soon borne to Heaven by angels. A sweet fragrance issues forth from his body, which (in all versions of the text) is said to be so heavy that it cannot be removed from his hermitage. Felice herself dies soon afterwards. The two are buried together in the hermitage (at least at first) and are said to be reunited in Heaven. The narrative thus shifts from being something like a chanson de geste to something much more hagiographical.

The two halves of Guy’s life are clearly displayed in the Rous Roll, which depicts and gives a brief history of each significant family member (historically real or otherwise) of the Beauchamp Earls of Warwick.

Guy’s later life is also the likely subject of two misericords in English cathedrals.

A number of literary antecedents to the figure of Guy have been posited. Many scholars, like Judith Weiss, point to the twelfth-century Le Moniage Guillaume (part of the William of Orange cycle) whose main character, Guillaume d’Orange (otherwise known as Guillaume au Court Nez), is a warrior who battles “Saracens” and later becomes a monk and then hermit, fearful for the state of his soul after having killed so many people (“The Exploitation” 44-46). As Angus Kennedy points out, it is also not uncommon in Arthurian romances, for example, for hermit-saints to have previously been members of the chivalric class (72). Both verse and prose French romances alike show a host of knights who choose to retreat from the world and end their days as hermits: the protagonist of Escanor; Perceval in Manessier’s Continuation and in the Queste del Saint Graal; at least thirteen knights in the Perlesvaus; Mordrain and Nascien, King Urien, Girflet, Bors and Hector, and even Lancelot in the Vulgate Cycle; Guiron and his ancestors in Palamède; and Pergamon in Perceforest (74-75). References to aristocratic hermits exist in many other texts, particularly Arthurian, but these hermits, as they are presented, are not entirely separated from the world. In fact, they very often still play a role in their societies (think of all of the other hermits in the Queste del Saint Graal) (77-78).

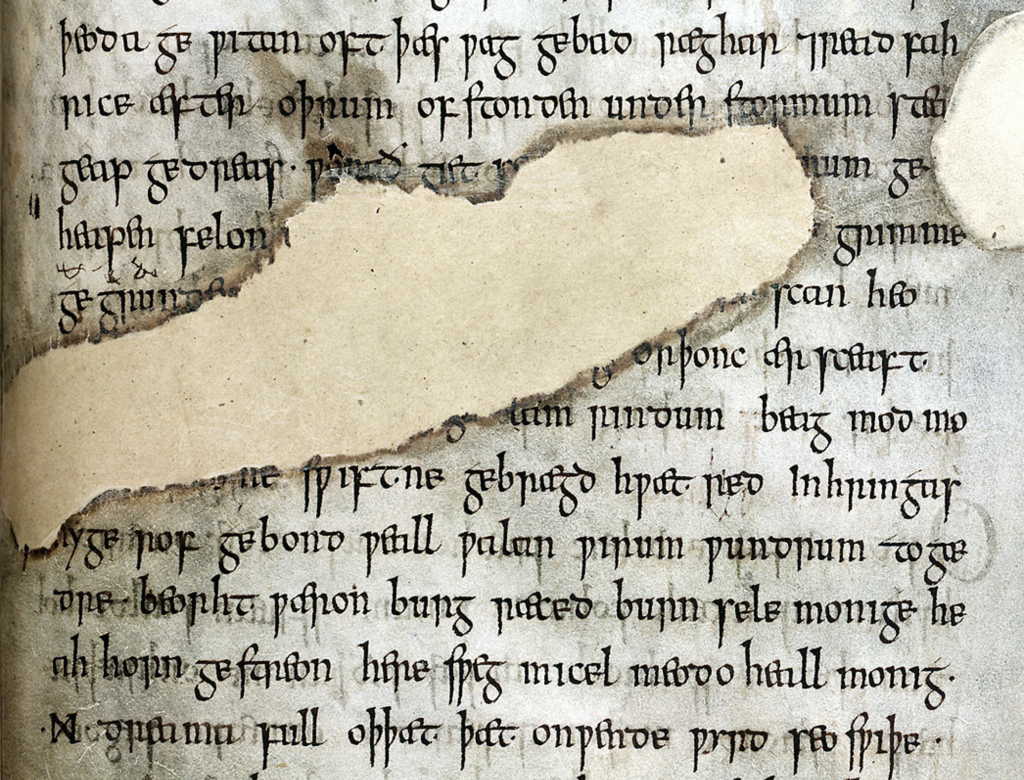

To my mind, however, there is an as yet unnoticed parallel with the late-eighth-century Old English lives of St. Guthlac in that invaluable repository of Anglo-Saxon poetry, the Exeter Book (Exeter, Cathedral Library, MS 3501). (For some images, go here. The lives are based, at least in part, on the Latin Vita sancti Guthlaci (between 730 and 749 A.D.) written by a man named Felix, likely a monk, about whom next to nothing is known. Guthlac, though, was born around 673 A.D. into a royal Mercian family and had a military career before becoming a monk at Repton Abbey and then two years later a hermit in the Lincolnshire fens at what is now Crowland (Croyland in the Middle Ages). He died there in 714, and a shrine was erected to commemorate him. Around this eventually grew Crowland Abbey and around this the town (Bradley 248-249).

In the Exeter Book’s Guthlac A (ff. 32v-44v), the saint is said to be attacked by demons who try to tempt him into abandoning his hermitage by making him feel guilty for leaving his family. They also seek to make him feel lonely, to crave human company. Guthlac ultimately resists, but we have here the same tensions that we see exhibited in later works like the legend of St. Alexis and Guy’s narrative. The events that are most reminiscent of Guy’s story, however, are those found in Guthlac B (ff. 44v-52v). Guthlac has a servant who attends to him, much as Guy the hermit does as well, and it is to this person that Guthlac makes a prediction, told to him by an angel, that he has eight days left to live (ll. 1034b-1038a). Shortly before his death, Guthlac has the servant boy prepare to seek out his most cherished virgin sister, “wuldres wynmaeg,” to tell her that he has kept apart from her for so long so that he could attain an eternal life, free from imperfections, with her in Heaven (l. 1345a; ll. 1175a-1196a). Guthlac dies before his sister, who is to bury him in his hermitage, comes; sweet odor issues forth (ll. 1271b-1273a); and his soul is borne to Heaven by angels (ll. 1305a-1306a). We see the same knowledge of impending death delivered by an angelic presence in Gui de Warewic and later versions, many of the very same details regarding Guy’s death, and the sister’s role is easily replaced by the wife’s—which also acts to make familial tensions that much greater. So then, is Guy meant to be a saint? That, dear reader, is a question for another post…or a book.

Hannah Zdansky, Ph.D.

University of Notre Dame

Bibliography (Cited and/or Suggested):

N.B. This list is not exhaustive.

Primary Sources (with introductions, notes, and commentary)

Boeve de Haumtone and Gui de Warewic: Two Anglo-Norman Romances. Trans. Judith Weiss. Tempe: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2008. 97-243.

Cambridge University Library MS Ff.2.38. Ed. Frances McSparran and P. R. Robinson. London: Scolar Press, 1979.

Felix’s Life of Saint Guthlac. Ed. and Trans. Bertram Colgrave. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1956.

Gui de Warewic: Roman du XIIIe Siècle. Ed. Alfred Ewert. 2 vols. Paris: Champion, 1932-1933.

“Guthlac A.” Anglo-Saxon Poetry. Trans. S. A. J. Bradley. London: Everyman, 1982. 248-268.

“Guthlac A.” The Exeter Book. Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records. vol 3. Ed. George Philip Krapp and Elliott van Kirk Dobbie. New York: Columbia University Press, 1936. 49-72.

“Guthlac B.” Anglo-Saxon Poetry. Trans. S. A. J. Bradley. London: Everyman, 1982. 269-283.

“Guthlac B.” The Exeter Book. Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records. vol 3. Ed. George Philip Krapp and Elliott van Kirk Dobbie. New York: Columbia University Press, 1936. 72-88.

Speculum Gy de Warewyke. Ed. Georgiana Lea Morrill. Early English Text Society. e.s. vol. 75. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., 1898.

Stanzaic Guy of Warwick. Ed. Alison Wiggins. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, 2004.

The Auchinleck Manuscript: National Library of Scotland Advocates’ MS. 19.2.1. Ed. Derek Pearsall and I. C. Cunningham. London: Scolar Press, 1977.

The Guthlac Poems of the Exeter Book. Ed. Jane Roberts. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979.

“The Irish Lives of Guy of Warwick and Bevis of Hampton.” Ed. and Trans. F. N. Robinson. Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie 6 (1908): 9-338.

The Romance of Guy of Warwick. Edited from the Auchinleck MS. in the Advocates’ Library, Edinburgh, and from MS. 107 in Caius College, Cambridge. Ed. Julius Zupitza. Early English Text Society. e.s. vols. 42, 49, 59. London: N. Trübner & Co., 1883, 1887, 1891.

The Romance of Guy of Warwick. The Second or 15th-Century Version. Edited from the Paper MS. Ff.2.38 in the University Library, Cambridge. Ed. Julius Zupitza. Early English Text Society. e.s. vols. 25-26. London: N. Trübner & Co., 1875-1876.

Secondary Sources

Ailes, Marianne. “Gui de Warewic in Its Manuscript Context.” Guy of Warwick: Icon and Ancestor. Ed. Alison Wiggins and Rosalind Field. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2007. 12-26.

Byrne, Aisling. “The Circulation of Romances from England in Late-Medieval Ireland.” Medieval Romance and Material Culture. Ed. Nicholas Perkins. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2015. 183-198.

Cannon, Christopher. “Chaucer and the Auchinleck Manuscript Revisited.” The Chaucer Review 46 (2011): 131-146.

Cooper, Helen. “Guy as Early Modern English Hero.” Guy of Warwick: Icon and Ancestor. Ed. Alison Wiggins and Rosalind Field. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2007. 185-200.

Cooper, Helen. “Romance after 1400.” The Cambridge History of Medieval English Literature. Ed. David Wallace. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. 690-719.

Cooper, Helen. The English Romance in Time: Transforming Motifs from Geoffrey of Monmouth to the Death of Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Crane, Ronald S. “The Vogue of Guy of Warwick from the Close of the Middle Ages to the Romantic Revival.” PMLA 30 (1915): 125-194.

Crane, Susan. “Anglo-Norman Romances of English Heroes: ‘Ancestral Romance’?” Romance Philology 35 (1981-1982): 601-608.

Crane, Susan. “Guy of Warwick and the Question of Exemplary Romance.” Genre 17 (1984): 351-374.

Crane, Susan. Insular Romance: Politics, Faith, and Culture in Anglo-Norman and Middle English Literature. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

Djordjević, Ivana. “Guy of Warwick as a Translation.” Guy of Warwick: Icon and Ancestor. Ed. Alison Wiggins and Rosalind Field. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2007. 27-43.

Djordjević, Ivana. “Nation and Translation: Guy of Warwick between Languages.” Nottingham Medieval Studies 57 (2013): 111-144.

Dyas, Dee. Pilgrimage in Medieval English Literature, 700-1500. Woodbridge: D. S. Brewer, 2001.

Echard, Siân. “Of Dragons and Saracens: Guy and Bevis in Early Print Illustration.” Guy of Warwick: Icon and Ancestor. Ed. Alison Wiggins and Rosalind Field. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2007. 154-168.

Edwards, A. S. G. “The Speculum Guy de Warwick and Lydgate’s Guy of Warwick: The Non-Romance Middle English Tradition.” Guy of Warwick: Icon and Ancestor. Ed. Alison Wiggins and Rosalind Field. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2007. 81-93.

Fellows, Jennifer. “Printed Romance in the Sixteenth Century.” A Companion to Medieval Popular Romance. Ed. Raluca L. Radulescu and Cory James Rushton. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2009. 67-78.

Field, Rosalind. “From Gui to Guy: The Fashioning of a Popular Romance.” Guy of Warwick: Icon and Ancestor. Ed. Alison Wiggins and Rosalind Field. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2007. 44-60.

Frankis, John. “Taste and Patronage in Late Medieval England as Reflected in Versions of Guy of Warwick.” Medium Aevum 66 (1997): 80-93.

Gordon, Sarah. “Translation and Cultural Transformation of a Hero: The Anglo-Norman and Middle English Romances of Guy of Warwick.” The Medieval Translator. Traduire au Moyen Âge. Ed. Jacqueline Jenkins and Olivier Bertrand. Turnhout: Brepols, 2007. 319-331.

Gos, Giselle. “New Perspectives on the Reception and Revision of Guy of Warwick in the Fifteenth Century.” Journal of English and Germanic Philology 113 (2014): 156-183.

Griffith, David. “The Visual History of Guy of Warwick.” Guy of Warwick: Icon and Ancestor. Ed. Alison Wiggins and Rosalind Field. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2007. 110-132.

Hanna, Ralph, III. “Reconsidering the Auchinleck Manuscript.” New Directions in Later Medieval Manuscript Studies: Essays from the 1998 Harvard Conference. Ed. Derek Pearsall. York: York Medieval Press, 2000. 91-102.

Hopkins, Andrea. The Sinful Knights: A Study of Middle English Penitential Romance. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990.

Kennedy, Angus J. “The Portrayal of the Hermit-Saint in French Arthurian Romance: The Remoulding of a Stock-Character.” An Arthurian Tapestry: Essays in Memory of Lewis Thorpe. Ed. Kenneth Varty. Glasgow: French Department of the University of Glasgow, 1981. 69-82.

King, Andrew. “Guy of Warwick and The Faerie Queene, Book II: Chivalry through the Ages.” Guy of Warwick: Icon and Ancestor. Ed. Alison Wiggins and Rosalind Field. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2007. 169-184.

Klausner, David N. “Didacticism and Drama in Guy of Warwick.” Medievalia et Humanistica 6 (1975): 103-119.

Legge, Mary Dominica. Anglo-Norman Literature and Its Background. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963.

Matthews, David. “Whatever Happened to Your Heroes? Guy and Bevis after the Middle Ages.” The Making of the Middle Ages. Ed. Marios Costambeys. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2007. 54-70.

Merisalo, Outi. “La fortune de Gui de Warewic à la fin du Moyen Âge (XVe siècle).” Le Moyen Âge par le Moyen Âge, même: réception, relectures et réécritures des textes médiévaux dans la littérature française des XIVe et XVe siècles. Ed. Laurent Brun and Silvère Menegaldo et al. Paris: Champion, 2012. 239-253.

Mills, Maldwyn. “Structure and Meaning in Guy of Warwick.” From Medieval to Medievalism. Ed. John Simons. London: Macmillan, 1992. 54-68.

Mills, Maldwyn. “Techniques of Translation in the Middle English Versions of Guy of Warwick.” The Medieval Translator II. Ed. Roger Ellis. London: Centre for Medieval Studies, University of London, 1991. 209-229.

Poppe, Erich. “Narrative Structure of Medieval Irish Adaptations: The Case of Guy and Beves.” Medieval Celtic Literature and Society. Ed. Helen Fulton. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2005. 205-229.

Price, Paul. “Confessions of a Godless Killer: Guy of Warwick and Comprehensive Entertainment.” Medieval Insular Romance: Translation and Innovation. Ed. Judith Weiss, Jennifer Fellows, and Morgan Dickson. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2000. 93-110.

Richmond, Velma Bourgeois. The Legend of Guy of Warwick. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1996.

Rouse, Robert Allen. “An Exemplary Life: Guy of Warwick as Medieval Culture-Hero.” Guy of Warwick: Icon and Ancestor. Ed. Alison Wiggins and Rosalind Field. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2007. 94-109.

Shonk, Timothy A. “A Study of the Auchinleck Manuscript: Bookmen and Bookmaking in the Early Fourteenth Century.” Speculum 60 (1985): 71-91.

Shonk, Timothy A. “The Scribe as Editor: The Primary Scribe of the Auchinleck Manuscript.” Manuscripta 27 (1983): 19-20.

Spahn, Renata. Narrative Strukturen im Guy of Warwick: Zur Frage der Überlieferung einer mittelenglischen Romanze. Tübingen: G. Narr, 1991.

Quin, Gordon. Introduction. Stair Ercuil ocus a Bás. The Life and Death of Hercules. Ed. and Trans. Gordon Quin. Dublin: Irish Texts Society, 1939. xiii-xl.

Weiss, Judith. “Gui de Warewic at Home and Abroad: A Hero for Europe.” Guy of Warwick: Icon and Ancestor. Ed. Alison Wiggins and Rosalind Field. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2007. 1-11.

Weiss, Judith. “The Exploitation of Ideas of Pilgrimage and Sainthood in Gui de Warewic.” The Exploitations of Medieval Romance. Ed. Laura Ashe, Ivana Djordjević, and Judith Weiss. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2010. 43-56.

Wiggins, Alison. “A Makeover Story: The Caius Manuscript Copy of Guy of Warwick.” Studies in Philology 104 (2007): 471-500.

Wiggins, Alison. “Are Auchinleck Manuscript Scribes 1 and 6 the Same Scribe? The Advantages of Whole-Data Analysis and Electronic Texts.” Medium Aevum 73 (2004): 10-26.

Wiggins, Alison. “Guy of Warwick in Warwick?: Reconsidering the Dialect Evidence.” English Studies 84 (2003): 219-230.

Wiggins, Alison. “Imagining the Compiler: Guy of Warwick and the Compilation of the Auchinleck Manuscript.” Imagining the Book. Ed. Stephen Kelly and John J. Thompson. Turnhout: Brepols, 2005.

Wiggins, Alison. “The Manuscripts and Texts of the Middle English Guy of Warwick.” Guy of Warwick: Icon and Ancestor. Ed. Alison Wiggins and Rosalind Field. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2007. 61-80.

Zupitza, Julius. “Zur Literaturgeschichte des Guy von Warwick.” Sitzungesberichte der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philosophisch-Historische Classe. vol. 74. no. 1. Vienna: Karl Gerold’s Sohn, 1873. 623-668.