For this school year’s exciting inaugural post, Maidie Hilmo shares her request for a scientific analysis of the Pearl-Gawain manuscript (British Library, MS Cotton Nero A.x), containing the unique copy of the Middle English poems: Pearl, Cleanness, Patience, and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. It shows the kind of questions that help gain access to the viewing of original manuscripts and can result in a technological investigation of specific details. Bringing together science and art history, Hilmo has uncovered evidence that “the scribe was also the draftsperson of the underdrawings. It appears that the painted layers of the miniatures were added by one or more colorists, while the large flourished initials beginning the text of the poems were executed by someone with a different pigment not used in the miniatures.” The results of this request to the British Library—comprising the detailed report on the pigments by Dr. Paul Garside and a set of enhanced images by Dr. Christina Duffy, the Imaging Scientist — will become available on the Cotton Nero A.x Project website and, selectively, in publications by Hilmo, including: “Did the Scribe Draw the Miniatures in British Library, MS Cotton Nero A.x (The Pearl-Gawain Manuscript)?,” forthcoming in the Journal of the Early Book Society; and “Re-conceptualizing the Poems of the Pearl-Gawain Manuscript,” forthcoming in Manuscript Studies. To learn more, check out her special project here on our site.

The Pearl in the Dragon’s Belly

Hagiography, or the biographies of saints, was one of the most popular genres in the Middle Ages. This was because saints could be valuable moral exemplars: models of virtuous behavior that ordinary people were called on to admire and emulate. But they were also popular because exciting stories of the struggle between good and evil – and the miracles that saints performed – made for rollicking good tales, and vivid illustrations to go along with them. Some of the colorful tales of saints, like Patrick, Christopher, and Catherine, have already found their way into this blog. Today, I’d like to put the spotlight on Margaret of Antioch, one of my personal favorites, both for the dramatic story of her martyrdom, and especially for the beautiful iconography that makes her one of the easiest saints to recognize and identify in medieval art.

Margaret, or Marguerite, is, as all Francophiles will know, the French word for “daisy.” In Old French, it could also mean “pearl,” making the name a popular spur to etymological and allegorical puns. The most famous of these in English literature may be the poem Pearl (by the same author as Sir Gawain and the Green Knight), whose elegiac dream-vision about a dropped pearl is often read as a lament for the death of a young daughter probably named Margaret. And it is with this etymology – Margaret for pearl – that Jacob de Voraigne, the author of the Legenda Aurea (Golden Legend), one of the most widely read medieval collections of saints’ lives, began his life of St. Margaret. Margaret is a “pearl” for her humility, recalling the diminutive size of the jewel, and even more for the whiteness of her virgin purity. She was one of the many virgin martyrs of early Christianity, and her story resembles many others in its general outline.

She was raised by her nurse as a Christian, and grew into a remarkably beautiful young woman. But her beauty would be her downfall, as she caught the eye of the pagan prefect Olybrius. The lustful Roman wanted her for a wife or concubine, and ordered her brought to him. When he found she was a Christian, he demanded she convert, but she – refusing to betray her faith and wishing to maintain her virginity as part of her commitment to Christ – stood her ground. Olybrius ordered her tortured and thrown into prison to induce her to relent.

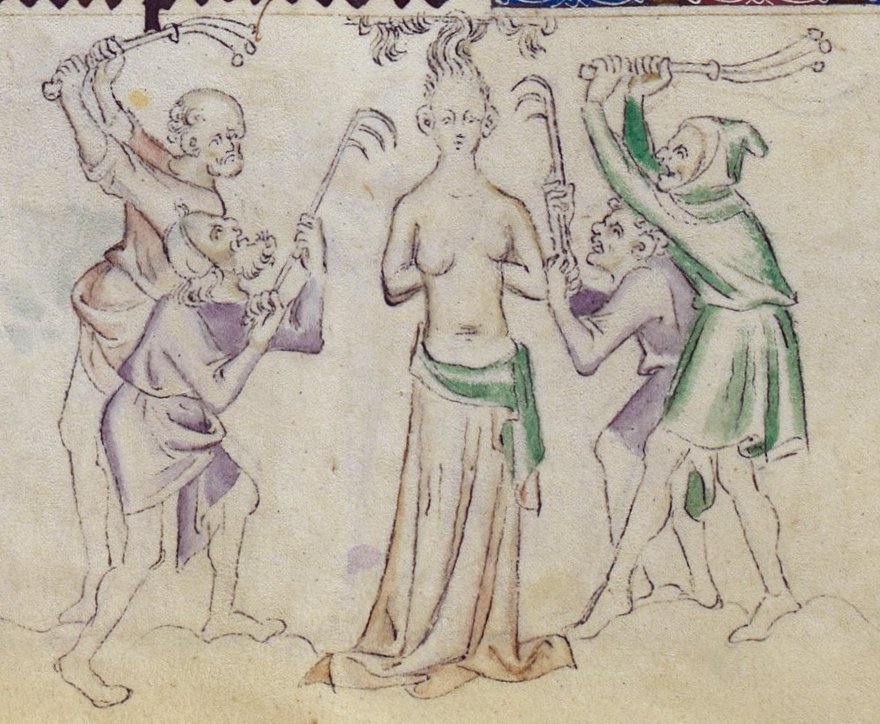

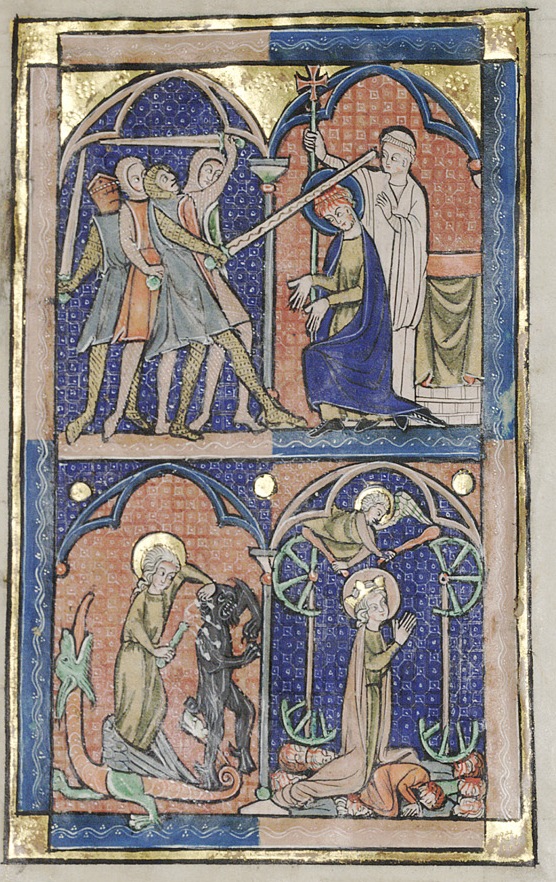

It is while Margaret was in prison that the narrative takes a distinctive turn. The sort of psychological warfare waged by Olybrius is distressing to Margaret, and so she prays to God for a more tangible opponent in her struggles. He obliges, and a dragon appears in her cell, which devours her whole. Margaret, however, is not so easily defeated – either by lusty pagans or by dragons – and makes the sign of the cross. On this action, the dragon bursts open, and Margaret emerges from his belly, whole and unharmed. It is this violent victory over fanged and fearsome evil that gives rise to the most popular way of depicting Margaret, sometimes in the act of emerging from a dragon’s belly and sometimes more sedately trampling it under her feet or holding it, subdued, by a leash or chain. Interestingly, while the story was the aspect of her tale that most caught artists’ imaginations, it was one that met with skepticism in the Latin hagiographic tradition, and which Jacob de Voraigne himself dismisses as apocryphal. This did not, however, dent its popularity in the vernacular tradition (see Cazelles, 216-217).

Once Margaret emerges from the dragon, her ordeal is not over. A second demon appears, this one in the shape of a man, described in some versions as hideous and black. He introduces himself as Beelzebub, and asserts that he has come to avenge his brother, the dragon, whom she has just killed (see Cazelles, e.g. 224). But this new foe is no more successful than the last: Margaret seizes him by the hair, and tramples him underfoot, beating him and interrogating him, before banishing him back to hell. Margaret’s physical victory over these demonic foes renders tangible her spiritual victory over her pagan captors – but from these she does not physically escape. After a further round of torture – during which her fortitude and miraculous invulnerability earn thousands of additional converts to Christianity – she is finally beheaded by the frustrated Olybrius.

While Margaret is a virgin saint, and indeed died to remain so, she is, somewhat incongruously, also the patron saint of pregnant women and women in childbirth. In her vita, this is presented as due to her dying prayer that those who invoke her aid might be healed and, specifically, that women who employ a copy of the book as a protective amulet during childbirth will be delivered of a healthy child. The explanation may also perhaps circle back to her association with the pearl, a gem Jacob de Voraigne asserts had medical use in staunching hemorrhaging blood, which could be a principal hazard during labor. Whatever the explanation for this connection, such powerful patronage no doubt contributed to her wide popularity.

Nicole Eddy

Postdoctoral Research Associate

Medieval Institute

University of Notre Dame

Works Cited

Brigitte Cazelles, The Lady As Saint : A Collection of French Hagiographic Romances of the Thirteenth Century (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1991).