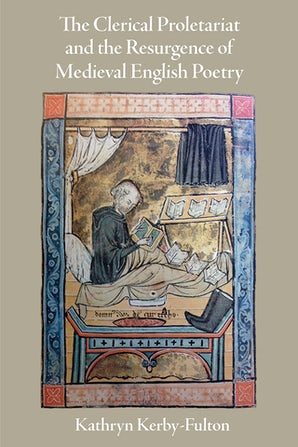

Educational training was the cornerstone of ecclesiastical and monastic life in the early medieval period, with the aim of producing knowledgeable clergy, who might then serve as spiritual and intellectual shepherds for their population. However, as Kathryn Kerby-Fulton explains in her recent monograph, The Clerical Proletariat and the Resurgence of Medieval English Poetry, because universities in the late Middle Ages were turning out more clergy than the church could hire in beneficed positions, many found themselves experiencing a crisis of vocation. Kerby-Fulton argues that this crisis produces a “clerical proletariat” many of whom ultimately become civil servants, secretaries in great households, writing office clerks, or casual liturgical laborers, especially in London. She shows how this crisis of mass underemployment is further exacerbated by pluralism (the unethical practice of hogging multiple benefices).

Beneficed priests were in a privileged position: they received both income from parish holdings and wealth from the church. Although medieval universities were producing highly educated clergy, there were more qualified candidates than ever before, while at the same time, beneficed priests were sometimes acquiring multiple benefices and then outsourcing the work of delivering the mass and managing the church operations to poorer paid vicars, chaplains and lesser church officials, while pocketing most of the money themselves.

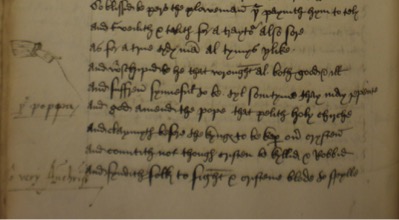

Kerby-Fulton argues that this sharp increase in qualified clergy and decrease in beneficed positions, resulted not only in a vocational crisis and the creations of a clerical proletariat, but ultimately in a resurgence in Middle English poetry, as this class of clerks saw more opportunities for writing English because they were working for the laity, though many still worked with Latin (or French) documents all day long. Figures like Thomas Hoccleve, a late medieval poet-clerk, comment regularly on the financial struggles and tenuous existences of the unbeneficed clerical proletariat, observable in his poem “The Complaint” which states:

I oones fro Westminstir cam,

Vexid ful grevously with thoughtful hete,

Thus thoughte I: ‘A greet fool I am

This pavyment a-daies thus to bete

And in and oute laboure faste and swete,

Wondringe and hevinesse to purchace,

Sithen I stonde out of al favour and grace.

“When once I came from Westminster, very bitterly troubled with burning anxiety, I thought like this: ‘I am a great fool to beat these streets like this every day and to work doggedly and sweat indoors and outdoors, in order to earn nothing but restlessness and misery, since I am fallen out of all good fortune and grace.’” (Jenni Nuttall, 183-189).

In this passage, we learn how Hoccleve is very upset with his vocational prospects (184), and he deems himself a greet fool “great fool” (185) for working endless and performing in and oute laboure faste and swete “firm and sweaty labor, indoors and outdoors” (187) with nothing to show for it but wondringe and hevinesse “wandering and hardship” (188).

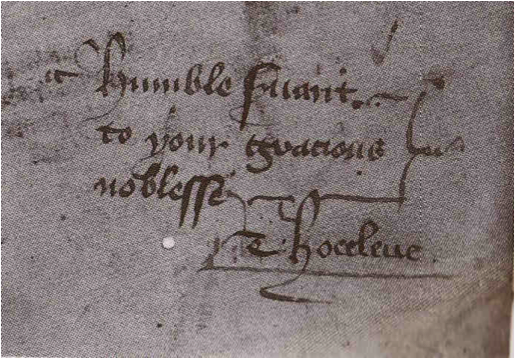

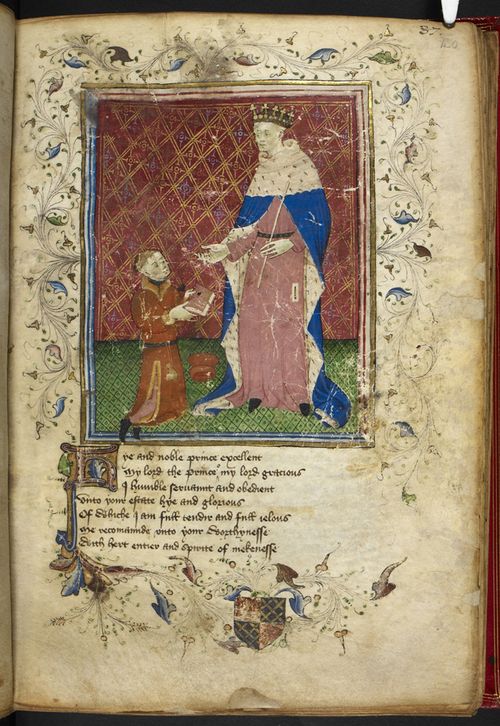

Similarly, in his poem, The Regiment of Princes, Hoccleve laments how he initially pursued the priesthood but ultimately forgoes these dreams and instead marries. Hoccleve describes his vocational rollercoaster, emphasizing that at first he sought Aftir sum benefice “after some benefice” but states that whan noon cam, / By procees I me weddid atte laste, “when none came, in time, I did wed at last” (1452-53). Moreover, Hoccleve stresses that his initial reluctance to marry is specifically because he long held hopes of a career as a beneficed priest, explaining that I whilom thoghte / Han been a preest “for a while I thought I would have been a priest” (1447-48). In both poems, Hoccleve expresses his frustration with the vocational crisis of underemployment which produces the clerical proletariat that Kerby-Fulton examines in her book.

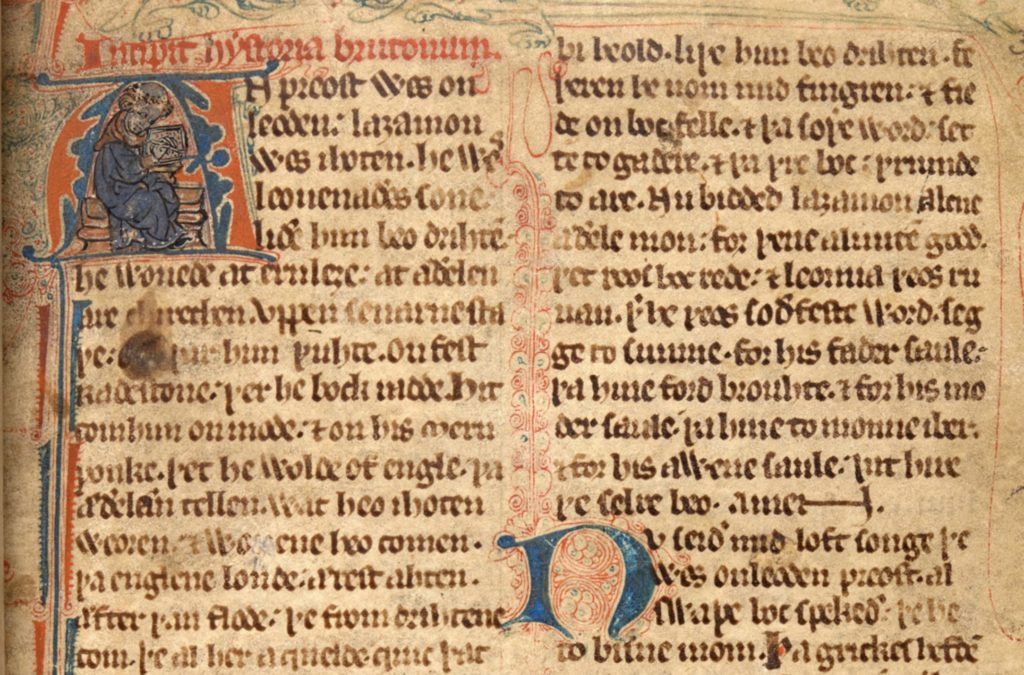

Members of the clerical proletariat loom large in Middle English literary culture, and various characters in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, including the Clerk of Oxenford, the hapless lover and parish clerk, Absolon (in the “Miller’s Tale“), and the noble Parson, who is perhaps the most virtuous figure on the pilgrimage. Similarly, William Langland (the author of Piers Plowman) was such a clerk, and likely so were the authors of the Owl and Nightingale and Laȝamon’s Brut. The University of Pennsylvania Press notes that “Taking in proletarian themes, including class, meritocracy, the abuse of children (“Choristers’ Lament”), the gig economy, precarity, and the breaking of intellectual elites (Book of Margery Kempe), The Clerical Proletariat and the Resurgence of Medieval English Poetry speaks to both past and present employment urgencies.”

Indeed, many modern untenured scholars (including myself), who work three or more academic jobs to pay the bills, will surely identify with the position Hoccleve voices in his complaint. As Kerby-Fulton insightfully observes in her book, the circumstances outlined in this late Middle English poem closely resemble the current crisis of vocation within modern academia, where well-paying tenured faculty positions are disappearing as the universities seek to outsource more and more of the work of education to adjunct professors, the modern equivalent of the late medieval clerical proletariat. Meanwhile, universities continue to produce an endless stream of highly skilled and qualified professionals, many of whom will sadly face chronic underemployment and even possible unemployment as a result of over-qualification and unethical practices now embedded in our private university system that is seemingly more concerned with profits than with the future of the academy.

Richard Fahey

PhD in English

University of Notre Dame

Further Reading & Selected Bibliography

Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Canterbury Tales. Harvard University: The President and Fellows of Harvard College, 2021.

Hoccleve, Thomas. The Regiment of Princes, ed. Charles R. Blyth. University of Rochester: TEAMS Middle English Text Series, 1999.

Kerby-Fulton, Kathryn. The Clerical Proletariat and the Resurgence of Medieval English Poetry. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021.

Laȝamon. Laȝamon’s Brut. Western Michigan University: Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse, 2019.

Langland, William. Piers Plowman, ed. Robert Adams, Patricia R. Bart, et. al. Piers Plowman Electronic Archive, 1994.

Nuttall, Jenni, trans. “Hoccleve’s ‘Complaint’: An Open-Access Prose Translation.” International Hoccleve Society, 2015.

Varnam, Laura, trans. “The Complaint Paramount [The Superlative Complaint] by Thomas Hoccleve.” Dr Laura Varnam, 2019.