I had not read far into Adam Gidwitz’s 2016 novel The Inquisitor’s Tale before wondering, “How does this guy know so much about the Middle Ages?” Upon flipping to the back of the book, I learned that Adam Gidwitz is married to a medieval historian. As a result, he had access to quality resources on the period, in the form of experts in the field and source materials, that made all the difference.

Clearly, he’s read Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales as the chapter titles mimic those of the canonical text. For instance, Gidwitz presents readers with “The Nun’s Tale” and “The Librarian’s Tale,” echoing Chaucer’s “Nun’s Priest’s Tale,” or “Clerk’s Tale.” Identifying the storytellers in those titles by their occupation, rather than their given name, imbues the story with more than a hint of the personification-style caricatures Chaucer provides of the medieval estates, referring to society’s organization by profession according to a religious and secular ranking system.[1] However, Gidwitz’s narrators diverge from the model text by telling their tales in multiple parts, whereas Chaucer’s, despite the Prologue’s stated ambitions for multiple tales per speaker, take one turn each. Nevertheless, this book makes for a good comparison text that could work in a class on the Canterbury Tales, or on literature influenced by it.

Aside from chapter and character titles, the book’s structure resembles that of the Canterbury Tales in one other significant way: the frame narrative. Chaucer presents readers with a collection of tales united into a single text by a larger narrative in which a group of pilgrims agree to the terms of a storytelling contest. However, instead of a frame narrative that brings together a series of disparate, standalone stories, unified only by that framing, Gidwitz tells one story through the perspectives of many storytellers, each of whom witnesses a different “chapter” of the narrative.[2] Like Chaucer’s narrators, Gidwitz’s speak in a tone and vocabulary suitable to their professional identities. The lead voice of the frame narrative comes from a soon-to-be reformed Inquisitor instead of a fictionalized authorial voice like the one Chaucer creates for himself. According to this Inquisitor, the nun speaks in an accent “as proper as any I’ve ever heard” (11). The Joungler with the most pronounced verbal idiosyncrasies clearly identifies his status through his speech: “I’m a jongleur. I’ll set me up in a market on market day, sing songs, juggle a little, whatever it takes to make a penny or two for poor boy like meself” (104). The wide strata of medieval classes and occupations represented at Gidwitz’ gathering of tale tellers also imitate Chaucer’s use of fictional narrators representing many levels of the medieval estates hierarchy. But, while Chaucer’s text remains incomplete (he died before finishing what would have been a monstrously large masterpiece), Gidwitz’s characters take multiple turns at storytelling in a fully realized novel.[3]

It makes sense for anyone with a background in English to have encountered Chaucer because of his consistent presence in the average undergraduate curriculum. However, the loose structural influence of the CanterburyTales on The Inquisitor’s Tales does not account for the depth of knowledge the book contains about a wide, wide range of all the most popular genres circulating in the Middle Ages (despite Chaucer’s use of pretty much all of them), nor does it account for his understanding of France where the story takes place, rather than England, the site of the Canterbury pilgrimage. Indeed, Gidwitz draws upon vitae(saints’ lives), miracle stories, chronicles, theological treatises, sermons, and more. The story even becomes a kind of pilgrimage for the protagonists with a holy destination, Mont-Saint-Michel, albeit the journey looks rather unconventional in comparison with many original source texts on pilgrimage, especially considering their ages and mixed religious affiliations.[4] Gidwitz likewise inserts his characters into actual medieval events (i.e.–the burning of Jewish books, or the lost Holy Nail) in historically important places (i.e.–Saint-Denis) among real people, such as Louix IX and his mother, Blanche of Castile.[5] These historical influences, as much as is possible in a fictional text, make the text feel authentic. The palpable presence of the Middle Ages derives from the breadth of primary and secondary sources from which Gidwitz draws, and it leaves the reader (or at least this medievalist) with a sense of authenticity absent in much of the modern medievalism I’ve encountered of late.[6] (Dare I mention Game of Thrones here?)

And then, to delight and assault the reader’s senses, there’s the matter of stinky cheese and a flatulent dragon. Dragons, of course, feature regularly in medieval texts, and saints regularly find themselves in battles with them. Gidwitz drew inspiration here from Saint Martha’s story in a popular collection of saints’ lives called The Golden Legend (350). As a specialist in English literature, it was impossible not to discern other literary echoes, such as the epic poem Beowulf, especially with the Beowulfian meadhall feasts that occur before and after every victory over a monster, including after Beowulf’s much fiercer and deadlier dragon. Or, perhaps more immediately, the feast scenes in Arthurian romances resonate here. The feasting hall often serves as site of serious political negotiations, and Jeanne, William, and Jacob must navigate these tricky conversations even as they are confronted with Époisses cheese that “tastes like being punched in the face” (137). Given the saintliness of the novel’s three children, a hagiographical source for the episode makes better sense than Beowulf, but recognizing parallels, even unintentional ones, is one of the great joys of reading. Moreover, because this book targets a younger audience, the humor injected into the narrative by the glorious cheese and stinky dragon counterbalances the weightier issues, such as the likely death of Jacob’s parents.

As a book historian, the illustrations just might be my favorite part of the book. While the illustrator, Hatem Aly, chose a more modern drawing style, he took care to base this style on common features of medieval manuscript decoration. Historiated initials (large, decorative letters with drawings inside them), vegetal borders, authoritative figures with their right hand in the declamatio position (raised with index finger pointing upwards), and wacky creatures lurking in the margins all grace the pages as visualizations and interpretations of the story. The artist’s development of a text-image relationship with an interpretative angle amounts to a form of reader response in line with common medieval practice. Gidwitz supports the text-image relationship with a healthy respect for the bookmaking process in a novel that writes manuscripts into the story’s central conflict: the burning of Jewish books. William the oblate’s comments here are particularly striking, and a great way to introduce younger audiences to book history:

A scribe might copy out a single book for years. An illuminator would then take it and work on it for longer still. Not to mention the tanner who made the parchment, and the bookbinder who stitched the book together, and the librarian who worked to get the book for the library and keep it safe from mold and thieves and clumsy monks with ink pots and dirty hands. And some books have authors, too, like Saint Augustine or Rabbi Yehuda. When you think about it, each book is a lot of lives. Dozens and dozens of them (305).

Based on the story’s reliance on book history, I could easily envision a writing assignment that asks students to close read an image or two alongside its corresponding text. Because the book caters to younger audiences, such an assignment could work across many grade levels, or even at the undergraduate level when framed appropriately.

Most importantly, at the center of this narrative sits a friendship that stands as a corrective to the religious intolerances so familiar to medievalists accustomed to staring down at hate-filled pages on occasion (not that this experience represents all the period’s literature). Jeanne, the main protagonist and a Christian peasant, befriends two boys: Jacob, a Jew, and William, an oblate (monk-in-training) with a Saracen mother (the standard, but not the most tolerant medieval term for a Muslim). Although widespread, such intolerances were neither universal, nor evenly applied in medieval texts, but they appear even in our most canonical medieval texts, such as Chaucer’s “Prioress’s Tale” with its severe anti-Semitism.[7] However, Gidwitz counters these earlier medieval narratives with a transformative friendship:

Just a few days ago, William and Jeanne would have begged Jacob to follow Christ, and save his soul from damnation. Now the idea of it seemed ludicrous. If God would save their souls, surely, surely, He would save Jacob’s, too. What difference was there between them, except the language in which he prayed? (262).

Such a sentiment might send some medieval theologians into a rage. But, even the more tolerant thinkers of the age tend to turn to conversion as their rationale, rather than understanding and accepting the coexistence of multiple faiths into their worldview. For example, in The Book of John Mandeville, a wildly popular text throughout nearly all of Europe, the narrator draws several parallels between the Muslim and Christian faiths, seeing Islam as similar enough to prompt greater conversion efforts and, therefore, greater tolerance. However, he does not apply such “generous” (extra emphasis on the quotations here) perspectives to the Jews, who he villainizes as friends of the Antichrist.[8] Gidwitz, in his efforts towards tolerance and understanding, veers intentionally and rightly from his source materials even while acknowledging the harsh, often dangerous, climate in which medieval Jews in Europe lived.

So, with all these accurate historical re-creations, does Gidwitz’s novel give us an exact replica of the Middle Ages? Well, no. That would require non-fiction and a time machine, a real life one. Ultimately, it’s a fiction novel for younger audiences. It contains crucial life lessons about cheese. Oh, and friendship, tolerance, and love, but all of that can be pretty well be summed up with cheese.

And one final point, why is it that the frame narrative’s characters do not realize the main speaker’s occupation? That’s easy: Nobody expects the Inquisition, Spanish or otherwise.[9]

Karrie Fuller, PhD

University of Notre Dame

Notes:

[1]To learn about different occupations’ rank in the social hierarchy, see Jill Mann’s Chaucer and Medieval Estates Satire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1973).

[2]Some of Chaucer’s tales circulate independently in manuscripts, especially religious ones, such as the “Tale of Melibee.”

[3]The use of a frame narrative, it should be noted, was not unique to Chaucer among medieval authors. Boccaccio’s Decameron represents the form in Italy, a country Chaucer visited multiple times where he encountered the works of Boccaccio, Dante, and other major authors on the continent.

[4]For those new to pilgrimage texts, a good place to begin might be The Pilgrimage of Egeria for an early example and William Wey for a much later example. While pilgrimage was a spiritual journey and texts most often reflect the seriousness of the experience, it could also be a form of tourism, and fictionalized versions, such as Chaucer’s, reflect this side of the journey to a greater degree. Dragons, and legends more generally, can fit into a pilgrimage narrative as The Book of Sir John Mandeville attests.

[5]Read the “Author’s Note” at the back of the book for more details.

[6]Some of Gidwitz’s sources appear in the back of the book in the “Annotated Bibliography.” It’s a good place to start for background reading.

[7]In addition to the Canterbury Tales itself, there are several commentaries on this topic right here on the Medieval Studies Research Blog. For a modern take on Chaucer’s anti-Semitism see this post on “Teaching the Canterbury Talesin the Alt-Right Era” by Natalie Weber. Find other relevant posts under the “Undergrad Wednesdays” category as well.

[8]Access an online version of Mandeville as part of the TEAMS Middle English Texts Series.

[9]If you need to read this footnote to understand the cultural reference here, please immerse yourself in the world of Monty Python immediately. It’s for your own good, really.

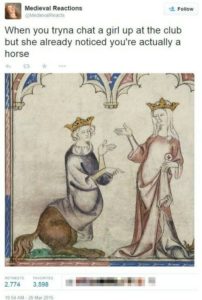

We’ve all seen the “I take 1000 selfies for every one I can post” Instagram admissions, and the smartphone videos where the gorgeous YouTube star turns this way and that to display how she can go from (ridiculously thin and good-looking) normal to supermodel quality with angles and makeup. These social media accounts have a rhetoric of their own. The “Feet in the foreground, beautiful scenery in the background” photo means ultimate relaxation. Twitter has its own grammar, often departing from “proper” English, that mashes up different vernaculars and changes from meme to meme.

We’ve all seen the “I take 1000 selfies for every one I can post” Instagram admissions, and the smartphone videos where the gorgeous YouTube star turns this way and that to display how she can go from (ridiculously thin and good-looking) normal to supermodel quality with angles and makeup. These social media accounts have a rhetoric of their own. The “Feet in the foreground, beautiful scenery in the background” photo means ultimate relaxation. Twitter has its own grammar, often departing from “proper” English, that mashes up different vernaculars and changes from meme to meme.