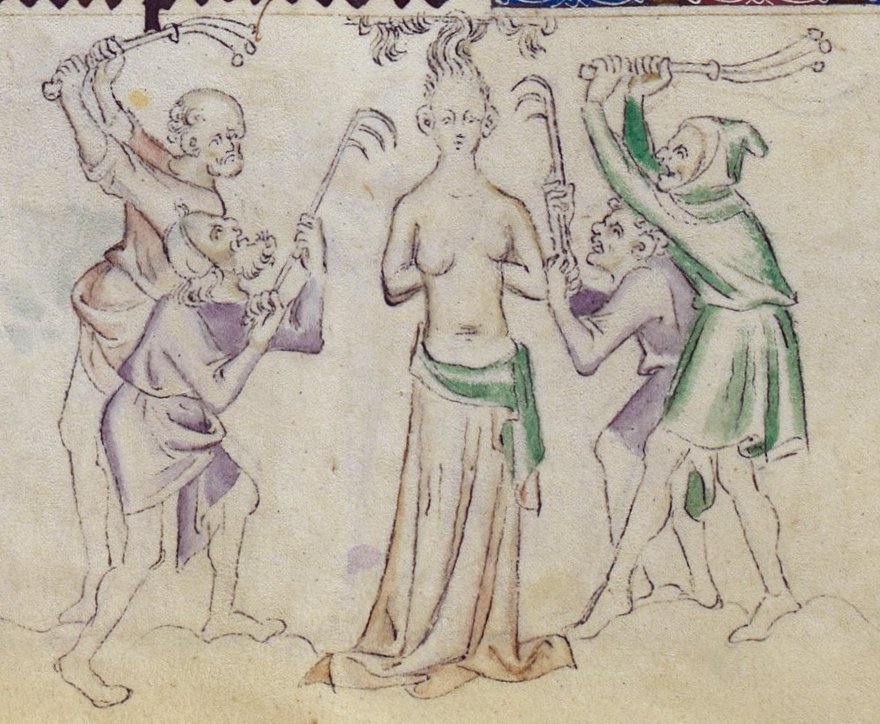

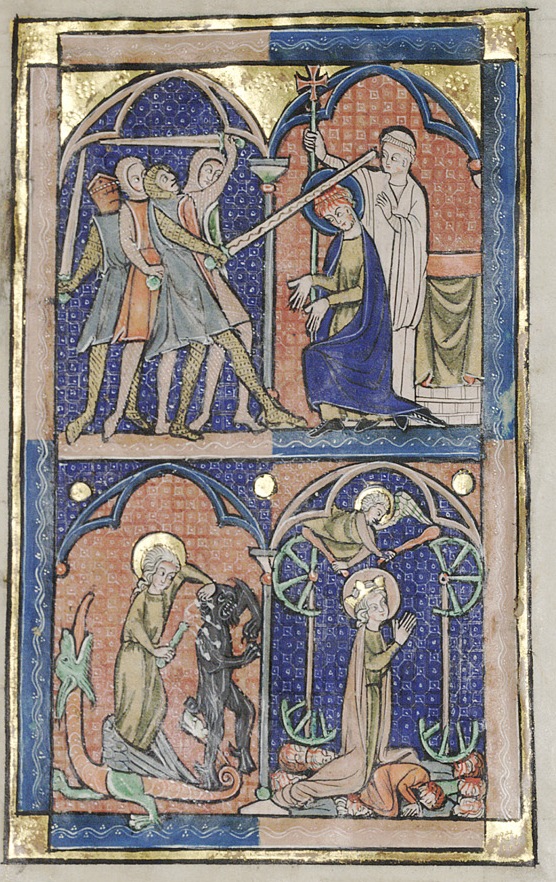

There is something curious and charming about an Old Testament classic receiving a courtly treatment (and not just in poetry, as any medieval tapestry admirer can attest. For a medieval tapestry rendering of Susannah and the Elders, see below).

This semester I was very enchanted by my encounter with The Pistil of Swete Susan. In this fourteenth-century retelling of Susannah and the Elders from the thirteenth chapter of Daniel, a narrative of resolute tenacity emerges, almost startlingly, from beneath a veil of lush alliterative verse. Contributing most notably to an initial and misleading association of Susannah and Joachim with an overindulged and naive version of noblesse and splendor is the speaker’s five-stanza elaboration upon that iconic emblem of courtly wealth and leisure, the garden. This elaboration marks a very substantial and deliberate departure from the one line that communicates the garden in the likely source texts, and it cannot be ignored. Though the significance of this disproportionately elaborate moment in the medieval adaptation has been the source of debate, it is likely that centuries of readers have been captivated with the Edenic association that the garden’s verdant portrait ushers into the Susannah story, and of course, in a narrative that also centrally features the theme of temptation, readers would have recalled the Genesis story. Though scholarship has cast Susannah as the Eve figure in the Genesis story, my research questions whether this might be an unfair association, and explores the idea that medieval audiences may have actually viewed the elders as the Eve figures—and might even have viewed Susannah as a Christological figure—gestures, informed by the garden elaboration, which would radically and fascinatingly contradict rigid gender stereotypes of the time period.

Under the umbrella of this primary topic, I also explore some subtopics. For example, I look at this poem’s version of an ideal medieval woman—for though Susannah is “wlonkest in weede”—or in other words, fashionable—the poem emphasizes her education and intellect more than it emphasizes her stylishness. I also look at The Pistil of Swete Susan’s place in an emerging medieval theme of ageism towards the elderly. For, in fourteenth century medieval literature, no longer is the elderly figure associated with sagacity, but he or she is now deemed deceitful and corrupt. I further discuss how the garden elaboration explicates these subtopics.

For me, though, the centerpiece of the poem is not the lush and flowing treatment of the tangled garden, but a moment of profound and moving straightforwardness that the juxtaposition with the garden serves only to emphasize. It is the moment of exchange between Susannah and Joachim after Susannah has been condemned. This moment is characterized not by a reaction of anger or fear that one would expect from pampered and entitled noblesse, but simply by the humble, and indeed Christological, imagery of hands and feet. As Susannah kisses Joachim’s hand and Joachim gently removes the fetters from Susannah’s feet, husband and wife become Christ for one another, and, in a gesture deeply countercultural to medieval beliefs, marriage becomes a stunningly sanctifying vocation.

Thei toke the feteres of hire feete,

And evere he cussed that swete.

“In other world schul we mete.”

Seide he no mare.

“The Pistel of Swete Susan”: 257-260

from Heroic Women from the Old Testament in Middle English Verse, edited by Russell A. Peck.

Honora Kenney

MA Candidate

Department of English

University of Notre Dame