In what follows, I would like to offer a little medley of anecdotes, originating from Ireland, Wales, or Anglo-Saxon England which I have either come across during my time as an undergraduate student, and remember very fondly, or have learned about more recently, and which have struck me as particularly fascinating. While my own background is in Celtic Studies, where I work especially on editing Old and Middle Irish texts (yes, from the original manuscripts), I’ve always had a fondness for the relationships that existed between various medieval civilisations and especially for contact between languages. During the year I spent as a Murphy Irish Exchange Fellow at Notre Dame, I also had the opportunity to study Greek and Latin with Profs. Mazurek and Mazurek, topping up on my knowledge of both of these languages pursued while studying in Ireland. Below are four tales of linguistic contact, demonstrating scribal cleverness and competition, some riddles, the danger of studying in Ireland, and also information about reindeer. I hope you’ll enjoy!

Nolite te grammatica carborundorum (or some actual Latin)

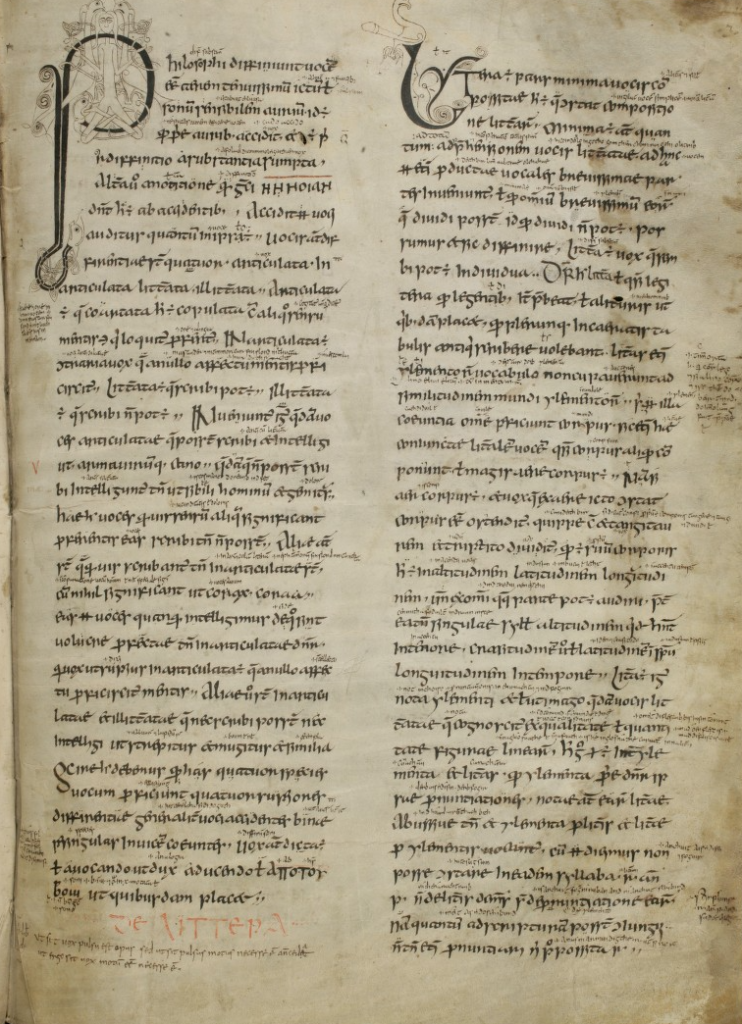

Every student of Old Irish, myself included, will at one stage have come across the Old Irish Glosses, and most of the time they will form the foundation of any beginner’s level Old Irish course. As a novice to this fascinating language, I naturally wondered what exactly glosses were and why they were so important. In John Strachan’s Old Irish Paradigms and Glosses, one of the standard teaching works, we find the complicated tables which ought to be learned off by heart by anyone wishing to have even the smallest sense of how the Old Irish verbal system works. But the bulk of the book is filled with practice sentences drawn from actual unadapted material (in contrast to the grammatical ‘safe-space’ that is E. G. Quin’s Old-Irish Workbook), and thus the adventurous student is plunged into the world of orthographical variation and grammatical uncertainty, the world of the Glosses. The primary sources for the student of Old Irish, which also provide the majority of the source material to Rudolf Thurneysen’s seminal Grammar of Old Irish, are interlinear and marginal notes written in Old Irish as commentary on Latin texts, found in manuscripts which are now, for the most part, kept in libraries in Continental Europe. One such source is a mid-ninth-century manuscript in the Stiftsbibliothek of St. Gallen in Switzerland, known as Codex Sangallensis904.[1] It contains a copy of Priscian’s Institutiones Grammaticae (6th century), one of the most important sources for the instruction of Latin in the Middle Ages.

To the student of Old Irish, this work is simply known as ‘the St. Gall Glosses’. As can be seen in the image below, the main text is written in large script, but in-between the lines and in the margins, we find much smaller annotations, explanations, and comments in Latin and in Old Irish. These are to a large extent explanatory teaching notes, as a knowledge of Latin was indispensable for understanding, studying, and also copying biblical texts, hagiography, or even computus.[2]

When studying a foreign language, be it ancient, medieval, or modern, it is only natural to ponder the ways in which that language is both alike and different from one’s own. And building a bridge between the familiar and the foreign is the mark of a good teacher as well as a good student. Among the glosses found in the Codex Sangallensis are numerous gems of language contact, which provide insight into the mind of the medieval Irish Latin teacher and of his students. An example familiar to many students of Old Irish will no doubt be the little nature poem written in the margin on ff. 203-4, here given from Gerard Murphy’s edition[3] together with Seamus Heaney’s and Timothy O’Neill’s translation:[4]

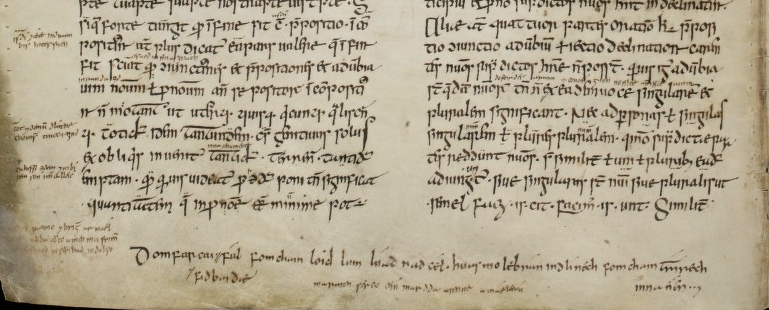

Dom-ḟarcai fidbaide fál

fom-chain loíd luin, lúad nād cél;

hūas mo lebrán, ind línech,

fom-chain trírech inna n-én.

Fomm-chain coí men, medair mass,

hi mbrot glass de dingnaib doss.

Debrath! nom-Choimmdiu-coíma:

caín-scríbaimm fo roída ross.

Pent under high tree canopy,

A blackbird, listen, sings for me,

Above my little book’s ruled quires

I hear the wild birds jubilant.

From a shrub covert, shadow-mantled

A cuckoo’s clear sing-song delights me.

O at the last, the Lord protect me!

How well I write beneath the wood.

This little poem is one of the highlights of medieval Irish nature poetry and was long held to be a reflection of the hermitic lifestyle of the medieval Irish monk until that assumption was challenged by Donnchadh Ó Corráin.[5] In what might feel more recent, but was still twenty years ago this year, Patrick Ford made a fascinating contribution to the subject in challenging ‘the conventional scholarship that ignores the physical setting in which we find it [the poem]’.[6] Ford was interested in the question, which had not before been asked, as to why this little poem had survived in this particular manuscript and on this particular page of Priscian’s Grammar, and confronted the practice of reading texts outside their manuscript contexts lest ‘the genre determines the meaning of the work’. But what exactly is the poem’s manuscript context?

On f. 203 in the St. Gall copy of Priscian’s Grammar, the reader is treated to a description of the Latin pronominal system (this is part of Book 12 of De Figuris), specifically the distinctions between simple and compound pronouns, e.g. huiusmodi, mecum, etc. With this manuscript context in mind, Ford has made the ingenious argument that the scribe, far from musing about blackbirds and cuckoos, very much had pronouns on his mind.[7] One of the most distinctive features of Old Irish (and, to a certain extent, also Welsh) are infixed pronouns. In the Old Irish verbal system, both the subject and the object of an action were expressed within the verbal complex, the former through the ending of a synthetic verb form, e.g. finnamar ‘Let us find out’, and the latter through a pronoun that was either suffixed to the verbal ending or inserted before the main verb with the help of a preverb or other particle. Thus, ‘He kills his enemy’ (as you do) is marbaid a námait, but ‘He kills him’ is either marbthai with a suffixed pronoun or na marba with an infixed pronoun (and the conjunct particle no as well as the dependent form of the verb). There is nothing equivalent to the infixed pronoun in Latin, however. Given that our little nature poem contains six pronouns in the space of eight lines, five of which are infixed pronouns and one possessive, Ford concluded that the scribe was engaging both critically and creatively with Priscian’s text: he responded to the idiosyncrasies of Latin pronominal compounding in the most Old Irish way possible—with a poem filled with infixed pronouns.

While the poem of the scribe in the woods may be the most famous example of the creative interplay between Latin and Old Irish, it is far from the only one. The differences between Latin and Old Irish are most certainly not confined to the way both languages employ pronouns. One of the most striking differences between the two is the modal category of the infinitive. While most European languages have an infinitive (étudier, studieren, etc.), Irish does not. But that does not mean that Latin infinitives are not glossed in Priscian and other Latin texts containing Old Irish glossing. See, for instance, the following examples occurring in the Old Irish glosses to the commentary on the Psalms contained in the Codex Ambrosianus C 301 inf, another ninth-century Irish manuscript now held at the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan.[8] On f. 15a 10, the word inficere is glossed fris-n-orr, literally ‘that he may injure’; on f. 78b 24, the deponent infinitive opinari is glossed with an Old Irish deponent form du-menammar ‘that we may opine’; and on f. 39b 3, supplicare is glossed with ṅges ‘that he may pray’. The Old Irish solution for the lack of an infinitive was to put the verb into the present subjunctive and employ a sub-clause construction known as a nasalising relative clause (this nasalisation is indicated by the ninnges and before the verbal stem in fris-n-orr).

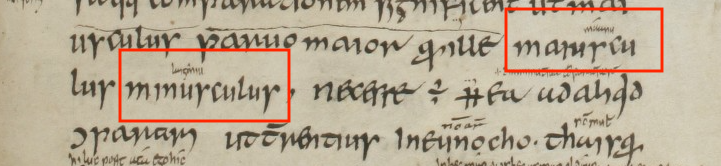

Dwelling for another moment on Priscian and the teaching of Latin in Irish monasteries, Irish scribes did not only ponder the differences between Latin and their own language, but also commented on the similarities or sought equivalent Irish solutions for a particular Latin phenomenon. A curious case of morphological creativity in the glosses on Priscian is the occurrence of what seem to be special comparative forms of certain adjectives. See for instance the two forms on f. 45, where the forms maánu ‘a little greater’ and laigéniu ‘a little smaller’ occur. These are to be understood as comparative forms of mór ‘great’ and becc ‘small’ (with adjectival suppletion) respectively, though their regular comparative forms are móo or máo and lagiu. The words glossed by máanu and laigéniu, respectively, are maiusculus and minusculus, again ‘a little greater’ and ‘a little smaller’.

It appears then that the Latin teacher wanted to make his students understand that –cul is a Latin diminutive suffix which can express variation in the degree of comparison, specifically to what extent something is lesser or smaller than something else. And the Irish equivalent of such a diminutive suffix is én or án. Thus, laigiu becomes laigéniu and móo becomes maánu, creating nonce words for the sake of teaching. The Old Irish Glosses are a veritable treasure trove, and any student or scholar versed in the reading of insular minuscule should set the Thesaurus Paleohibernicus, the standard edition of the Old Irish Glosses,[9] aside and look at the manuscripts directly. Fortunately, the St. Gall manuscript has been fully digitized and can be consulted free of charge.

Greek Substitution Cyphers, or ‘Are you smarter than an Irishman?’

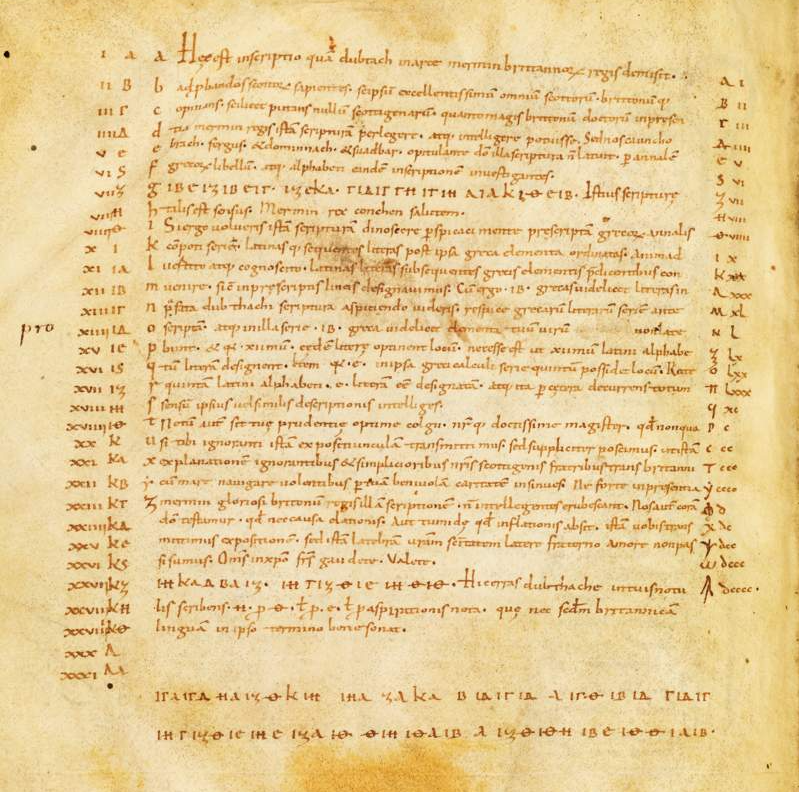

Our next stop on the journey of language contact is Wales, although we are taking a few Irish people along with us. One of the most intriguing riddles of medieval Western Christendom (in my not entirely unbiased opinion) is the cypher known as the ‘Bamberg Cryptogram’. So called after one of its manuscript sources, a late-tenth-century codex held at the Staatsbibliothek Bamberg in Bavaria, the context of the cryptogram goes back to an Irish scholar named Dubthach mac Máel Tuile whose obit is recorded in 869. Dubthach was a most learned man, versed not only in Latin and, to a certain extent, Greek, but also in computus, cryptography, and cryptanalysis.[10] The ‘Rosetta Stone’ to Dubthach’s cypher is provided by a letter written in Latin verse which gives the answer to the riddle (provided one is fluent in Latin, of course). This letter was sent by another Hiberno-Latin author named Suadbar, better known under the name Sedulius Scottus, another of the great ninth-century Irish scholars, to his master Colgu in Ireland. The context of the letter is Suadbar’s journey to the court of Merfyn Frych (d. 844), king of Gwynedd in North Wales, together with three companions. He tells us that scholars, such as himself and his fellow students, arriving from Ireland at the court of Merfyn are tested and given Dubthach’s cypher to decode.

ΙΒΕ ΙΖ ΙΒ Ε ΙΓ. ΙΖ Ε ΚΑ. Γ ΙΔ ΙΓ Γ Η ΙΓ. ΙΗ Α ΙΑ Κ ΙΘ Ε ΙΒ

If you have ever had any dealings with codes and cyphers (if not, I highly recommend Simon Singh’s The Code Book), it will be obvious to you that we are dealing with a simple substitution cypher using the Greek alphabet as the basis. In order to understand the message, Suadbar and his companions had to substitute Roman letters for the Greek ones by assigning a Greek letter to each letter in their own alphabet and proceeding alphabetically. The key for the cypher, as given on f. 109r of the Bamberg manuscript, is as follows:

| Α | Β | Γ | Δ | Ε | S | Ζ | Η | Θ | Ι | ΙΑ | ΙΒ | ΙΓ | ΙΔ | ΙΕ | ΙS | ΙΗ | ΙΖ | ΙΘ | Κ | ΚΑ | ΚΒ | ΚΓ |

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | t | u | x | y | z |

Equipped with this cryptanalytic tool, we can now read the above line as

MERMEN. REX. CONCHN. SALUTEM

As David Howlett explains in the commentary to his edition of the cryptogram,[13] the phrase is from the salutation of a letter from King Merfyn to Cyngen (Irish Conchen), king of Powys and brother to Merfyn’s wife Nest. The name of the king, Merfyn, in Welsh is here spelled in Irish orthography, where medial m would have the same phonetic value as f in Welsh, hence Mermen. Translated, the line means ‘Merfyn the king salutes Conchenn’. Let us hope that Suadbar’s fellow students back in Ireland were worthy of the answer!

Continue on to part 2.

Marie-Luise Theuerkauf, Ph.D.

University of Cambridge

[1]The complete manuscript is available here: https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/list/one/csg/0904.

[2]Ó Néill, Timothy, The Irish Hand. Scribes and Their Manuscripts from the Earliest Times. Cork, 2014: 30.

[3]Murphy, Gerard, Early Irish Lyrics. Dublin, 1956 (repr. 2007): 4.

[4]Ó Néill 2014: 30.

[5]Ó Corráin, Donnchadh, ‘Early Irish hermit poetry?’, in D. Ó Corráin, L. Breatnach, and K. McCone (eds.), Sages, Saints and Storytellers. Celtic Studies in Honour of Professor James Carney. Maynooth, 1989: 251-67.

[6]Ford, Patrick K., ‘Blackbirds, Cuckoos, and Infixed Pronouns. Another Context of Early Irish Nature Poetry’, in R. Black, W. Gillies, and R. Ó Maolalaigh (eds.).Celtic Connections. Proceedings of the 10thInternational Congress of Celtic Studies, 1999: 162-170; 162-3.

[7]Ford 1999: 168.

[8]For more information about this manuscript, go here: https://www.vanhamel.nl/codecs/Milan,_Biblioteca_Ambrosiana,_MS_C_301_inf.See a newly developed project on these glosses here: https://www.univie.ac.at/indogermanistik/milan_glosses/.

[9]Stokes, Whitley and John Strachan (eds.), Thesaurus Palaeohibernicus, 3 vols. Cambridge, 1903 (repr. 1987).

[10]Dubthach mac Máel Tuine, doctissimus Latinorum totius Europae, in Christo dormiuit‘Dubthach mac Máel Tuile, most learned of all the Latinists of Europe, died in Christ’ (Dáibhí Ó Cróinín, Early Medieval Ireland, 400-1200. London and New York, 1995: 236).

[11]The entire manuscript is digitized here: https://zendsbb.digitale-sammlungen.de/db/0000/sbb00000081/images/index.html?id=00000081&fip=216.183.48.102&no=1&seite=1&signatur=Msc.Class.6.

[12]Chadwick, Nora K., ‘Early culture and learning in North Wales,’ in N. Chadwick, K. Hughes, C. Brooke, and K. Jackson, Studies in the Early British Church. Cambridge, 1958: 29-120; 96.

[13]Howlett, David, ‘Two Irish Jokes’, in Pádraic Moran and Immo Warntjes (eds.), Early Medieval Ireland and Europe: Chronology, Contacts, Scholarship.A Festschrift for Dáibhí Ó Cróinín. Turnhout, 2015: 225-264; 243.