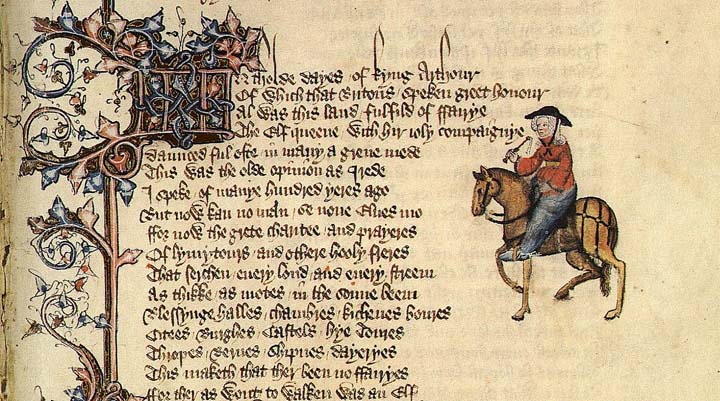

As a medievalist who is both interested and personally invested in the representation of women’s bodies, I am acutely aware of how our gendered ideology hearkens back to the Middle Ages. The ways in which the Canterbury Tales mirror contemporary discourse and practices around sexual violence are abundant, and though I know them well through my work with Chaucer, they remain alarming.

Needless to say, I was hardly surprised when, in October of 2016, Sonja Drimmer and Damian Fleming described in a blog post to In the Middle the remarkable relevance of the Miller’s Tale, in which Nicholas corners an unsuspecting Alisoun and grabs her by her genitals[i]:

“And prively he caughte hire by the queynte,

And syde, ‘Ywis, but if ich have my wille,

For deerne love of thee, lemman, I spille.’”[ii]

Used to describe Alisoun’s genitalia as “a clever or curious device or ornament,” the word “queynte” employs both of its Middle English definitions, as it is simultaneously a “punning” on a more modern derogatory term for the vaginal organs.[iii] That Alisoun “sproong as a colt dooth in the trave”[iv] to escape Nicholas’s hands on her vulva demonstrates that his fondling of her body is not only unexpected but also unwanted.[v] What Chaucer’s narrative describes is sexual assault.

Our own cultural conversation around sexual assault hasn’t ebbed since last fall. On the contrary, its media current seems to be only gaining momentum. On Tuesday, December 6, Time magazine revealed their 2017 Person of the Year: “The Silence Breakers,” the many women, as well as some men, who have recently been compelled to share their experiences as victims of sexual harassment and assault. Primarily composed of women’s voices, the massive movement demands that the men perpetuating this violence be held accountable for their actions. Meanwhile, Brock Turner, the former Stanford University student found guilty of three counts of felony sexual assault early last year, served only three months of a grossly lenient, six-month sentence in a county jail and began the process of appealing his conviction the same week as Time’s cover release.[viii] According to the New York Times, approximately 60 pages of the 172-page appeal document emphasize the intoxication of Turner’s victim on the night he raped her.[ix] As far as Turner is concerned, the violence he committed is still not his fault, suggesting that accountability can only take us so far, and, frankly, it’s not nearly far enough.

Current events have inspired me to return to the Canterbury Tales, this time to the Wife of Bath. In what is an often cited conundrum of the Wife’s tale, the knight who rapes the maiden at the story’s outset is rewarded at its end, while his female victim vanishes from the narrative entirely. While some critics see the maiden’s disappearance as a problematic act of erasure, I’d like to consider what can be achieved through the Wife’s attention to the rapist, rather than his victim.

In a tale that focuses more on remedy than reaction, the Wife conveys how the knight should not merely be punished but, rather, reformed. To weight the punishment Arthur initially proposes against the repercussions for contemporary sexual aggressors is a telling measure, as Arthur would have the knight executed for his actions. Guinevere, however, intervenes and – after her husband agrees that she should sentence the knight “at hir wille” – challenges him instead to discover what women desire most.[x] The quest upon which the knight embarks does not lead him to an explicit answer for her question, and his failure in this endeavor is, in my opinion, precisely the point: he must learn that women have wills of their own and understand that women’s wills should not be subsumed by men’s.

At the tale’s conclusion, it is only when the knight recognizes his wife’s will as equal to his own, a reflection of his reformed character, that he is rewarded. Admittedly, when the wife tells him he may choose to have her “foul and old” but “a trewe, humble wyf,” or “yong and fair” but unfaithful, neither option is ideal.[xi] But having just concluded her speech on “gentillesse,”[xii] through which she conveys how nobility originates in one’s character and is defined through one’s actions,[xiii] it would appear that the knight accepts the meaning of her words:

“My lady and my love, and wyf so deere,

I put me in youre wise governance;

Cheseth youreself which may be moost pleasance

And moost honour to yow and me also.”[xiv]

Not only does the knight address his wife with kindness and respect, but he also conveys that he has internalized the lesson she has taught him by deferring to her “wise governance” and imploring her to decide what kind of woman she wishes to be. Through his deliberate suspension of his own will to accommodate his wife’s, the knight demonstrates how his character has been reformed from the narrative’s beginning when he exerts his will over his female victim’s in his sexual assault on her body. In effect, the Wife of Bath’s Tale advocates for social reformation of masculinity as a proactive solution to sexual violence, situating punishment alone as a reactive and, thus, less productive response.

As a medieval scholar, I am dedicated to the idea that there is much we can learn from our past. As a literary scholar, I believe that studying literature can facilitate much of that learning. As a woman and a feminist, I wonder what can be gained by redirecting our collective gaze onto the perpetrators of sexual violence. Perhaps the Wife of Bath, a survivor of gendered violence herself, has a lesson she can teach us – and if there’s anything that can be learned, we must listen.

Emily McLemore

University of Notre Dame

[i] Drimmer, Sonja and Damian Fleming. “Not Subtle; Not Quaint.” In the Middle, 9 Oct. 2016.

[ii] Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Miller’s Tale. The Riverside Chaucer, edited by Larry D. Benson, Houghton, 1987, pp. 68-78, lines 3276-78.

[iii] Queynte] Middle English Dictionary, def. 1a, 2a.

[iv] Trave] an enclosure or a frame for restraining horses while they are being shod (Middle English Dictionary, def. b)

[v] Chaucer. The Miller’s Tale. The Riverside Chaucer, line 3282.

[vi] Chaucer. The Wife of Bath’s Tale. The Riverside Chaucer, pp. 116-22, lines 865-81.

[vii] Benson, Larry D. “The Canterbury Tales.” The Riverside Chaucer, pp. 8.

[viii] Stack, Liam. “Light Sentence for Brock Turner in Stanford Rape Case Draws Outrage.” New York Times, 6 Jun. 2016.

[ix] Salam, Maya. “Brock Turner is Appealing his Sexual Assault Conviction.” New York Times, 2 Dec. 2017.

[x] Chaucer. The Wife of Bath’s Tale. The Riverside Chaucer, lines 894-97.

[xi] Chaucer. The Wife of Bath’s Tale. The Riverside Chaucer, lines 1219-26.

[xii] Chaucer. The Wife of Bath’s Tale. The Riverside Chaucer, line 1211.

[xiii] Gentillesse] nobility of birth or rank, or nobility of character or manners (Middle English Dictionary, def. 1a, 2a)

[xiv] Chaucer. The Wife of Bath’s Tale. The Riverside Chaucer, lines 1230-33.