The day has suddenly turned to night; King Arthur and his knights are all frightened; and Guinevere, who is accompanying the entourage, begins to cry when out of nowhere the woods ring with terrible sounds of howling and wailing and grievous lamentation. A female-seeming being approaches Sir Gawain, having risen from a lake, and

Bare was the body and blak to the bone,

Al biclagged [clotted] in clay uncomly cladde […].

On the chef [head] of the cholle [neck],

A pade [toad] pikes [bites] on the polle [skull],

With eighen [eyes] holked [sunken] ful holle [hollow]

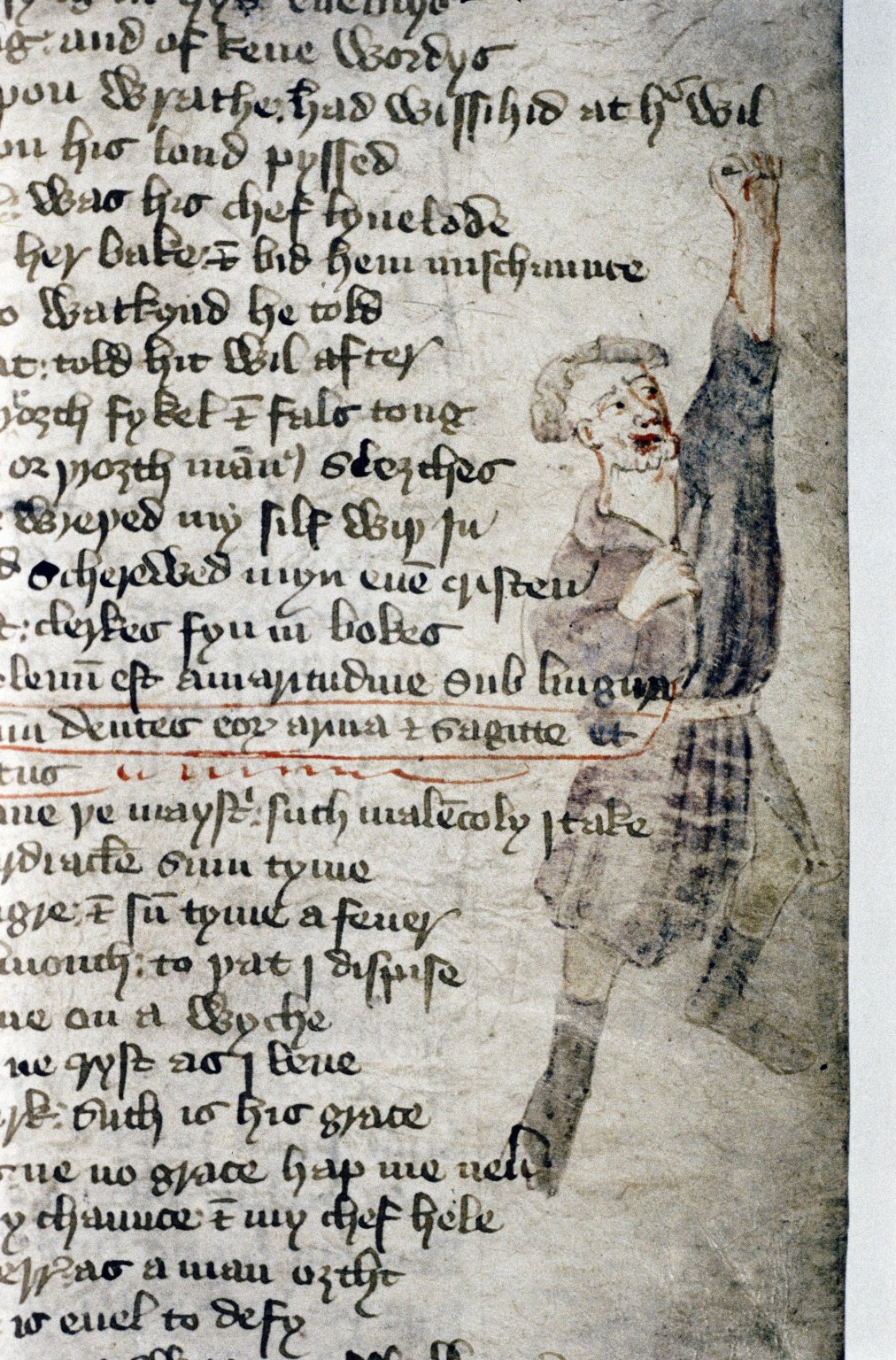

That gloed [glowed] as the gledes [coals]. (ll. 105-106, 114-117)[1]

The apparition continues to yell and murmur and groan as if it were mad and is shrouded in some sort of unfathomable clothing, covered by toads and circled on all sides by snakes.

Gawain finds his courage and, brandishing his sword, demands that the specter give an account of herself. She concedes, saying that she was once a queen—the fairest in the land—and was wealthy and privileged beyond compare, even more so than Guinevere. But now she is dead, having lost all—her body a filthy, rotting corpse—and, she says, “God has me geven of his grace / To dre [suffer through] my paynes in this place” (ll. 140-141).

The place that she is referring to is the Tarn Wadling, a lake in Cumbria, just south-east of Carlisle by about ten miles.[2] Tarn (< ME terne, tarne) is a word that originated as a local northern English term (< ON *tarnu, tjorn, tjörn) meaning ‘a lake, pond, or pool,’ but it has since come to be used to mean specifically ‘a small mountain lake, having no significant tributaries.’[3]

King Arthur and crew come upon the Tarn Wadling during a hunt in Inglewood Forest. The finery of the court—and especially of Guinevere—is described in several stanzas, much as the ghost describes the splendor she once enjoyed a number of stanzas later. After Gawain talks with her for a bit, she begs to see and speak to Guinevere. We quickly find out why, for she proclaims to Guinevere, “Lo, how delful [doleful] deth has thi dame dight [left]” (l. 160)! The spirit is her mother, and she urges Guinevere to “Muse on my mirrour” (l. 167). Death will leave her in such a fashion too if she does not give thought to her actions and the afterlife.

“[…] I, in danger and doel, in dongone I dwelle,

Naxte [nasty] and nedefull, naked on night.

Ther folo me a ferde [troop] of fendes of helle;

They hurle me unhendely; thei harme me in hight [violently];

In bras and in brymston I bren as a belle [bonfire].

Was never wrought in this world a wofuller wight. (ll. 184-189)

While Guinevere’s mother advocates for compassion and generosity, we discover, however, that it was lust and the breaking of her marriage vows that landed her in torment. These sins bear obvious relation to Guinevere’s own life, and the author doesn’t even feel the need to clarify. Her mother is a mirror.

Before Guinevere’s mother departs, Gawain pipes in, having clearly been listening. He asks about those nobles and knights who enter other’s lands in territorial expansion, crushing under their heels the people and seizing the glory and the riches without any right. Now, if anyone is familiar with Gawain, this is rather too self-aware for his character—clearly the author is speaking here. The royal wraith responds by denouncing Arthur as too covetous a king and saying that the court should be wary. The second half of the Awntyrs deals precisely with these problems of excess and conquest, and I leave this part of the plot for readers to explore on their own.

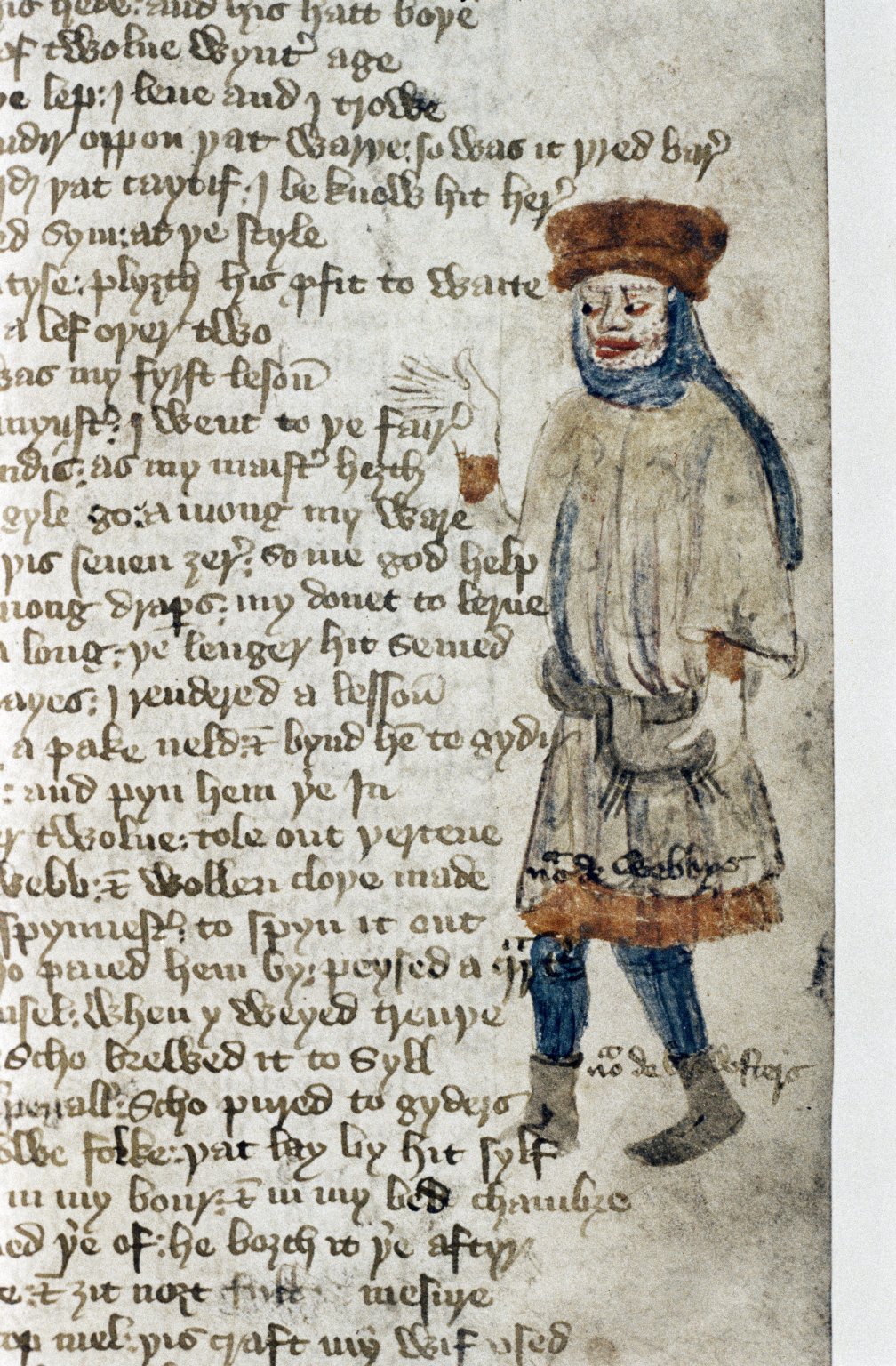

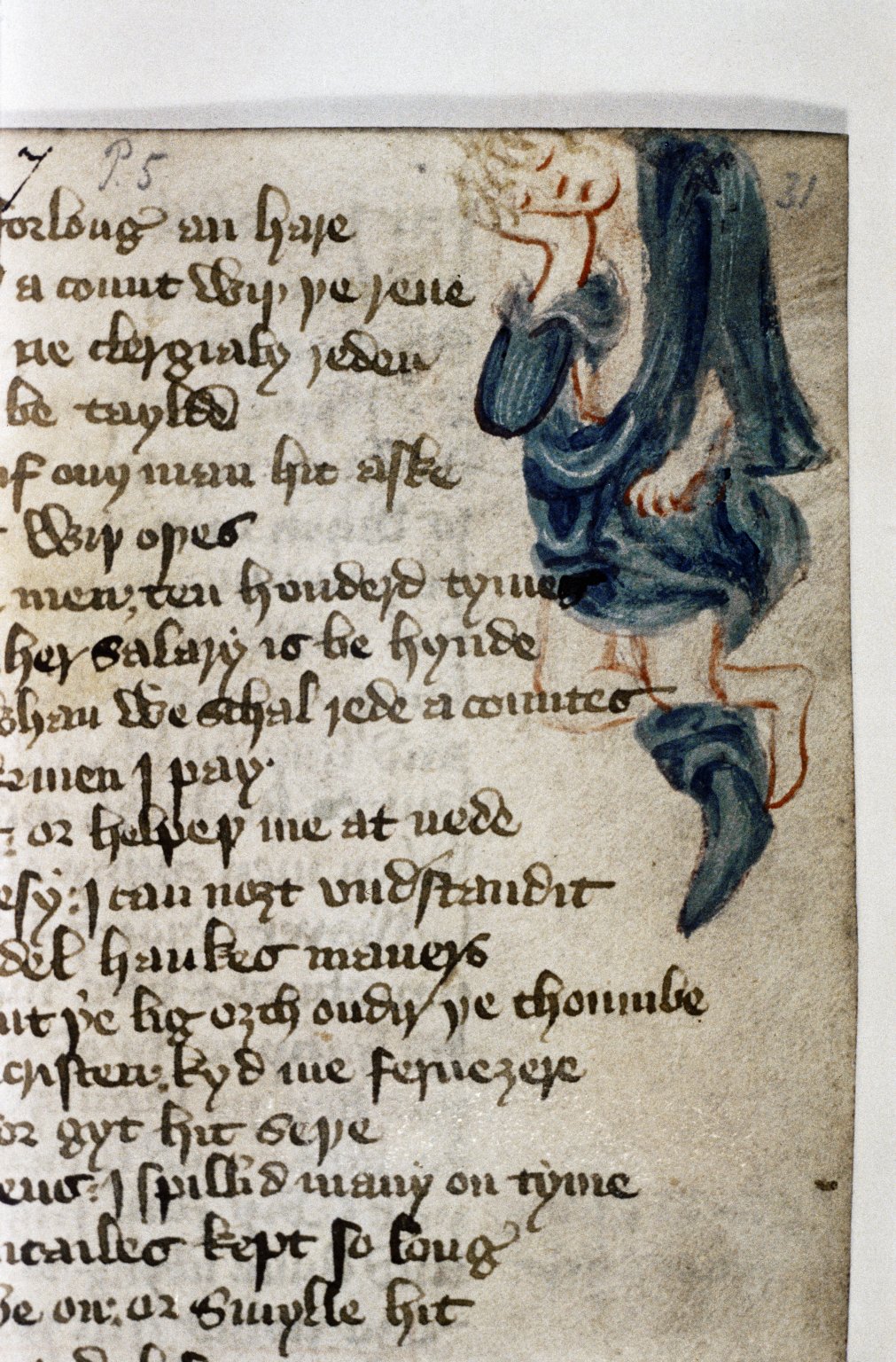

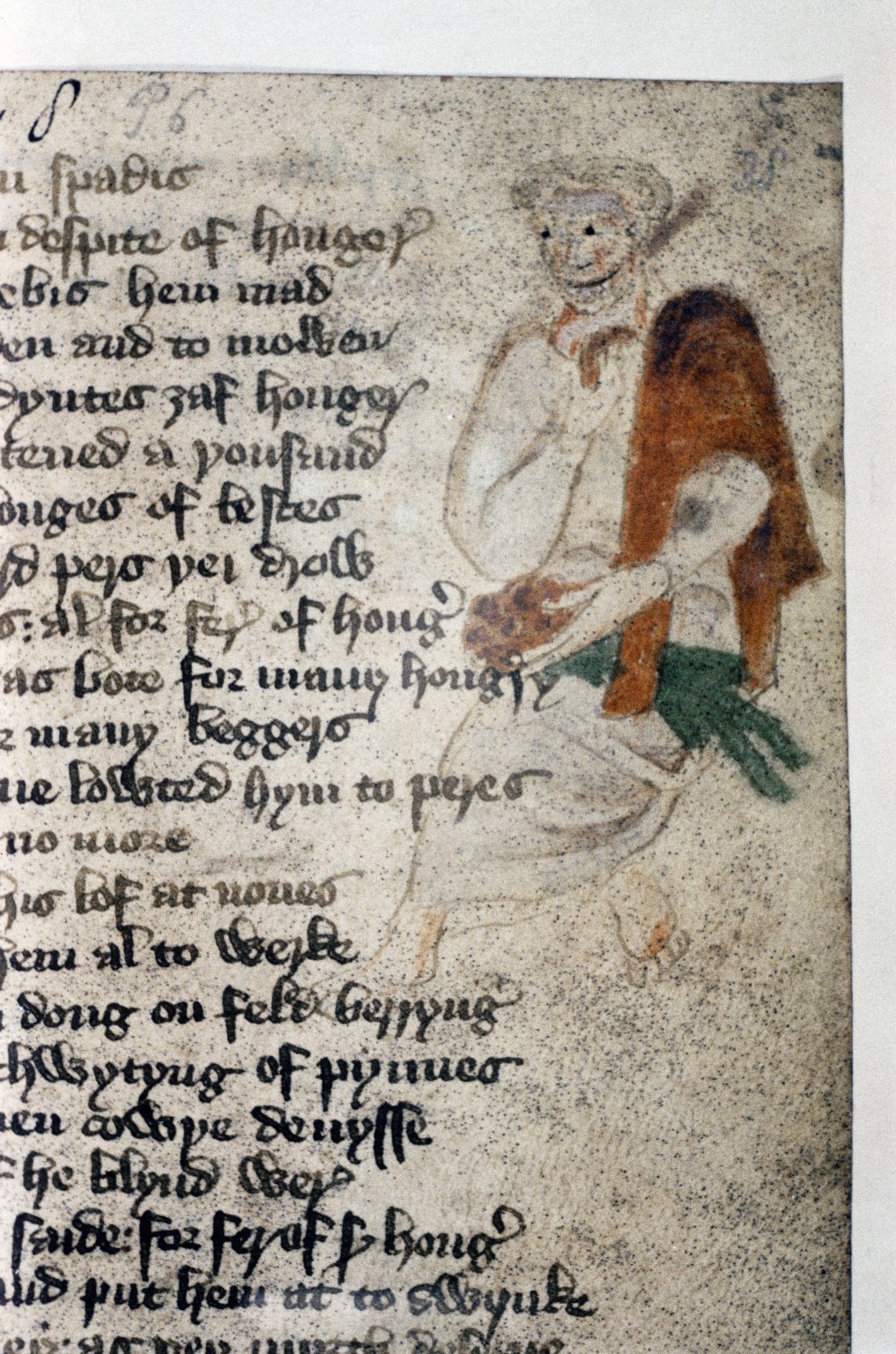

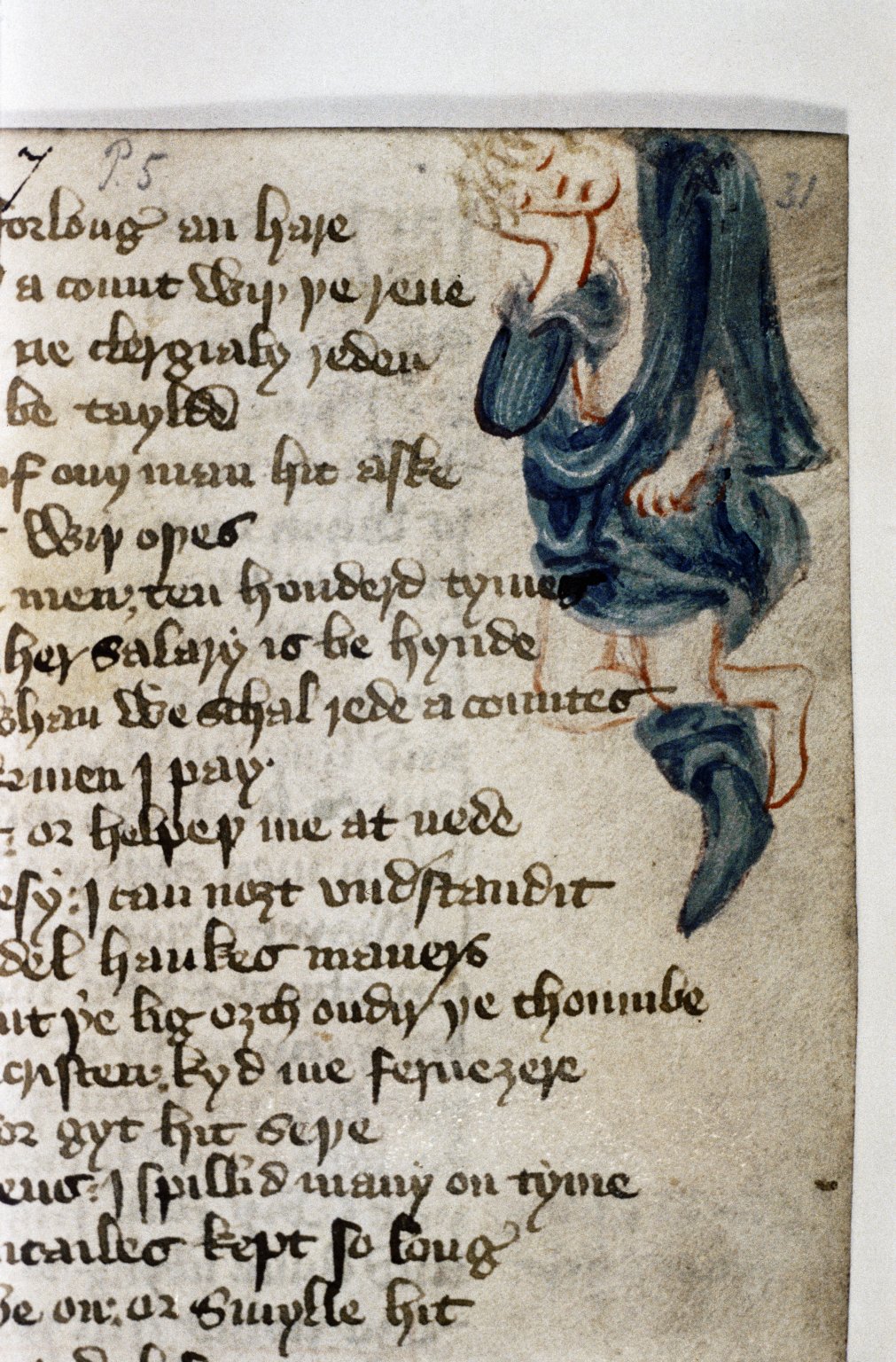

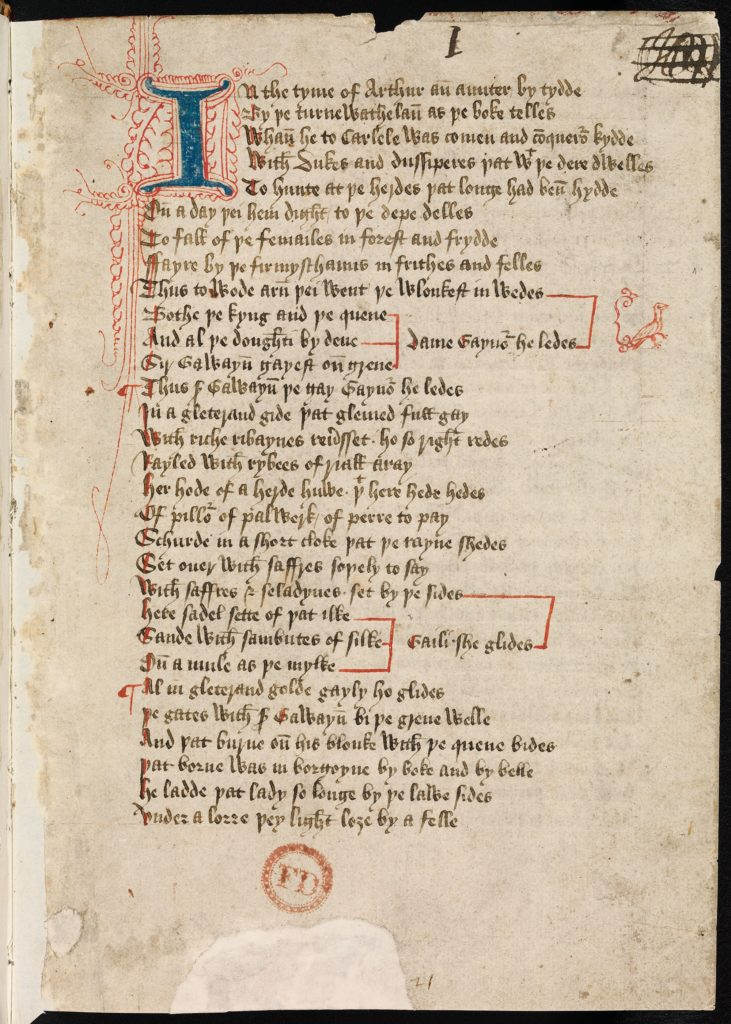

Concerning the fifteenth-century text that has reached us, it is preserved in four manuscripts: Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Douce 324; London, Lambeth Palace Library, MS 491.B; Lincoln, Lincoln Cathedral Library, MS 91 (Thornton Manuscript); and Princeton, Princeton University Library, MS Taylor 9 (Ireland Blackburn Manuscript).

Be this as it may, the Tarn Wadling has always been eerie, emitting strange sounds and even once having an island appear and then disappear. It is hard to say whether it was due to a desire to bring an end to the place and quash superstitions or increase his arable land and acreage that Lord Lonsdale ordered the lake to be drained and filled in sometime during the nineteenth century.[8] Sadly, the tarn itself is no more, but the stories persist—as perhaps do the spirits.

Hannah Zdansky, Ph.D.

University of Notre Dame

[1] The edition used is the following: “The Awntyrs off Arthur.” Sir Gawain: Eleven Romances and Tales. Ed. Thomas Hahn. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, 1995. This can be found online here: http://d.lib.rochester.edu/teams/text/hahn-sir-gawain-awntyrs-off-arthur. And here is an introduction: http://d.lib.rochester.edu/teams/text/hahn-sir-gawain-awyntyrs-off-arthur-introduction.

[2] You can find information about the location here: https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/visiting-woods/wood/4726/tarn-wadling/.

[3] See the entry “tarn” in the Oxford English Dictionary as well as “terne” in the Middle English Dictionary.

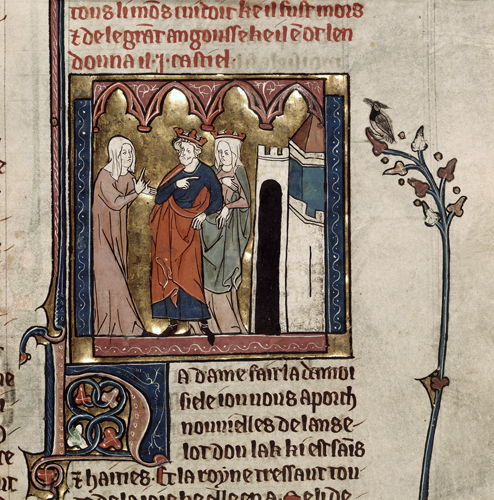

[4] The entire manuscript is digitized here: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Royal_MS_20_d_iv. Dated c. 1300-1380, it contains part of the Lancelot of the Vulgate Cycle. The image shows Arthur and Guinevere receiving news from a damsel.

[5] See the catalogue description with some images here: https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/record.asp?MSID=18463&CollID=27&NStart=10293. This manuscript contains another copy of the Lancelot, c. 1316.

[6] See images here: https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/inquire/Discover/Search/#/?p=c+0,t+,rsrs+0,rsps+10,fa+,so+ox%3Asort%5Easc,scids+,pid+f03eea52-0af3-4ff7-9069-c41a4b2f6c6b,vi+6e581efc-2391-4258-b621-0f85fe45f40f. You can find more information here: http://medievalromance.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/A_ghostly_encounter.

[7] On this, see especially David N. Klausner’s “Exempla and The Awntyrs of Arthure.” Medieval Studies 34 (1972): 307-25. Thomas Hahn provides further reading, editions with introductory material as well as scholarly articles, at the end of his introduction (see note 1).

[8] For more on the history of the Tarn Wadling, go here: https://www.cumbriacountyhistory.org.uk/tarn-wadling-background.