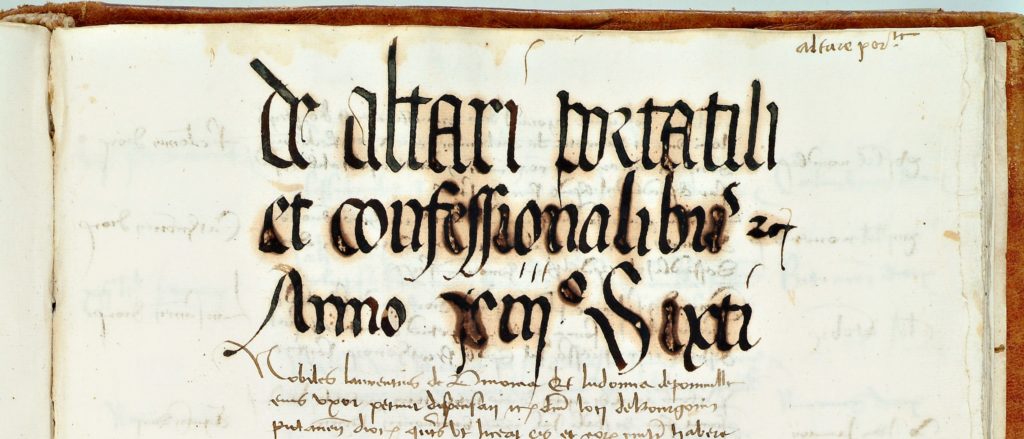

As the and papacy and its various offices grew in complexity throughout the Late Middle Ages, a plethora of new religious possibilities opened to non-elites across Western Europe. One such papal office, called the Apostolic Penitentiary, provided the opportunity for common parishioners to have the precious religious privileges that the medieval nobility had fought for two centuries to solidify and perpetuate. The Apostolic Penitentiary granted special dispensation for a variety of religious requests by parishioners across Western Europe, requests beyond the authority of their bishops to grant. Such requests could involve an approval of a marriage that was within four degrees of relationship through blood or marriage, approval for a portable altar so that the petitioner might be able to celebrate mass regardless of location, or an appeal by a supplicant for a new confessor outside of their parish priest. By the fifteenth century, a well-to-do townsperson in Ghent could enjoy many of the same personal religious privileges of the Duke of Burgundy in form, if not in grandeur.

Christians from every diocese in Western Europe could write to the Penitentiary via a special letter called a supplicatio, or a supplication. A supplication contained the name of the supplicant, perhaps some personal information about that person such as their profession or class, the diocese from which the request originated, and the date upon which the supplication was processed by the Penitentiary. Receipts of these supplications were collected by the Penitentiary and organized into yearly registers. One such example of a supplication for a new confessor can be seen below:

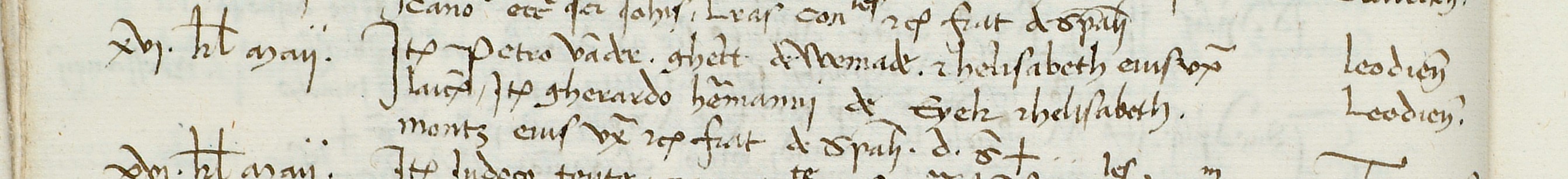

As with most supplications, the entry above is heavily abbreviated based on the sheer number of requests the Penitentiary received. It reads: Item Petro van der Ghert de Venrade et Helisabeth eius uxor laici et Gherardo Hermanni de Eyck et Helisabeth Montz eius uxor Leodiensis diocesis petunt litterae confessionalibus fiat de speciali. Datum 16 Maii 1456.

Translated: Peter van der Ghert of Venrade and his wife Elisabeth and Gerard Hermanni of Eyck and his wife Elisabeth Montz, laypeople of the diocese of Liege seek letters of confession (the right to choose a new confessor was called litterae confessionalibus). Granted under special papal mandate on the 16th of May 1456.

The most important part of this entry for our purposes here is the word laici, whereby the supplication indicates that the two couples from Venrade and Eyck were simple laypeople. They were not nobiles or clerici, nobles or clerics, two common appellations within the Penitentiary registers. All that was needed for a layperson to send a supplicatio from their diocese to the Apostolic Penitentiary was a fee. The exact cost of the fee varied, but it was certainly not prohibitively expensive, as many non-elites are represented in the records of the Penitentiary. Indeed, laici appear to have supplicated far more often to the Apostolic Penitentiary than to the similarly suited office, the Papal Chancery.

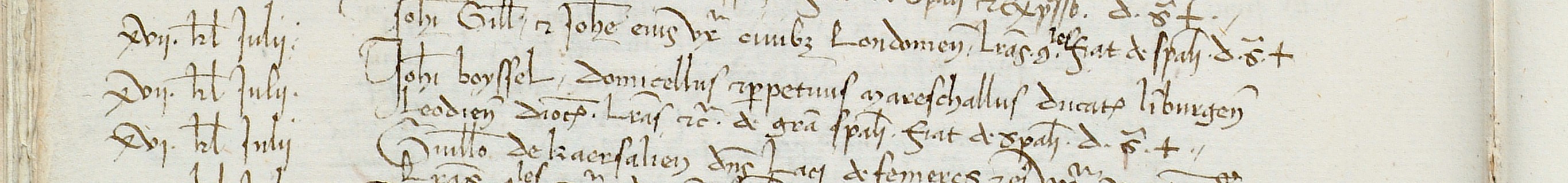

However, for many elites hoping to replicate their social superiors, they too had to go through the supplication process to the Penitentiary:

Transcription: Johannes Boyssel domicellus et perpetuus mareschallus ducatus Limburgen. Leodiensis diocesis.: petit litteras confessions de gratia speciali fiat de speciali D. s. t. 17 Julii 1456.

Translation: John Boyssel, young lord and ducal marshal in perpetuity of Limburg, in the diocese of Liege seeks a letter of confession…17th of July 1456.

Above we see John Boyssel, who is of a much higher social and political standing than the earlier entry in the supplications above. Boyssel is a perpetuus ducatus mareschallus, or a ducal marshal, and thus a lifetime appointee by either the Duke of Burgundy, or, more likely, the Duke of Limburg to this military position. Such a personage is a particularly striking inclusion in the registers of the Penitentiary. Boyssel’s appointment placed him among secular lords allowed to act in the stead of the dukes themselves. That Boyssel had to go through the same channels as commoners, possibly his own subjects, within the diocese of Liege, speaks to the social leveling effect of the Apostolic Penitentiary.

Sean Sapp, PhD Candidate

University of Notre Dame

Bibliography:

Archivio Segreto Vaticano, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registrum 6, f. 16v, 28v.

Clarke, Peter D. “New evidence of noble and gentry piety in fifteenth-century England and Wales,” Journal of Medieval History 34 (2008): 23-35.