As a child of the 1990s, I remember well when US currency turned into a magic trick to show your other classmates in school: hold a bill up to the light and a president’s face would stare back at you. This “trick” was simply a watermark. In the late 1990s, American bills began to be printed with watermarks, those presidents’ faces, to deter counterfeiters. The watermark is not a modern innovation, nor was it created to prevent counterfeiting. It was a medieval creation, one used primarily to show the maker of the paper, but also the place in which the paper was made, and (less often) when the paper was made.

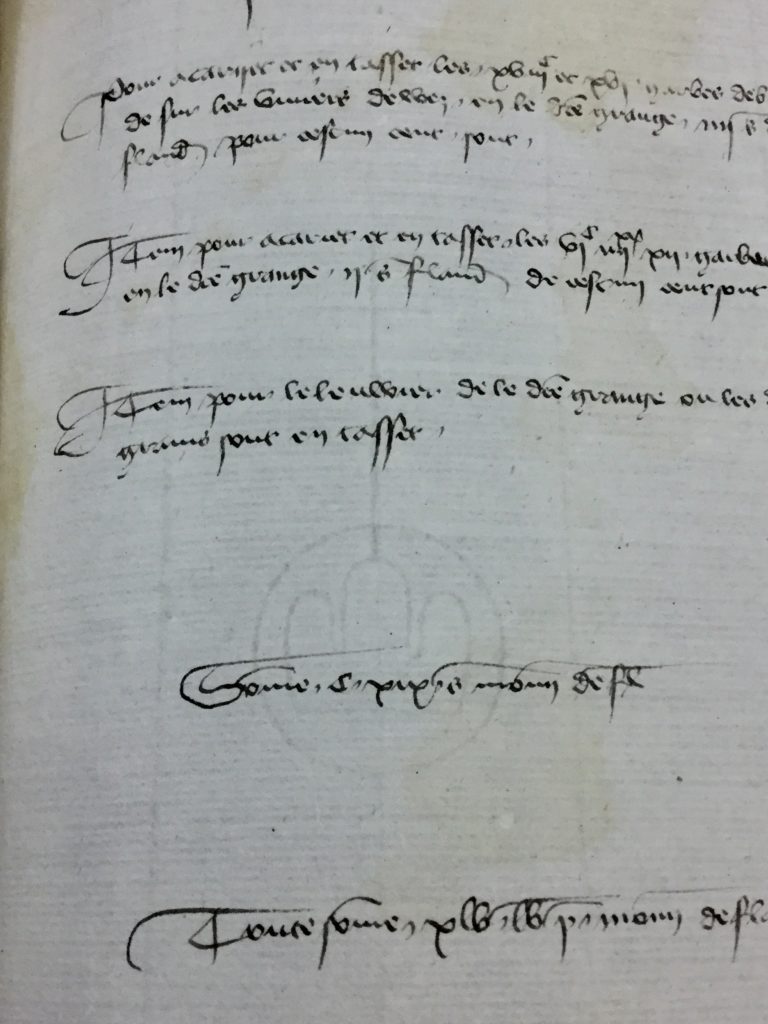

For this blog, I would like to discuss the risks of this third purpose of medieval watermarking- using watermarking as a means to date paper. I will rely upon two manuscript collections of the Rijksarchief te Gent, numbers K91 and K98, to demonstrate the uncertainty of watermark dating. Holding K98 is a “verzameling watermerken”- a collection of medieval watermarks beginning in 1386 and ending around 1500. The watermarks come from the Abbey of Saint Bavo’s in Gent, a prominent and powerful abbey within the medieval city.

The watermark collection is indeed just that- a bundle of loose leaves of paper, that for the most part, are not medieval at all. In examining the bundle of paper, one sees watermarks with an assigned date of the mark in the top left corner of the page, ranging from the late fourteenth to the late fifteenth century. However, most of the paper upon which these watermarks are imprinted or drawn are from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, with some drawings added later on carbon paper in the twentieth century.

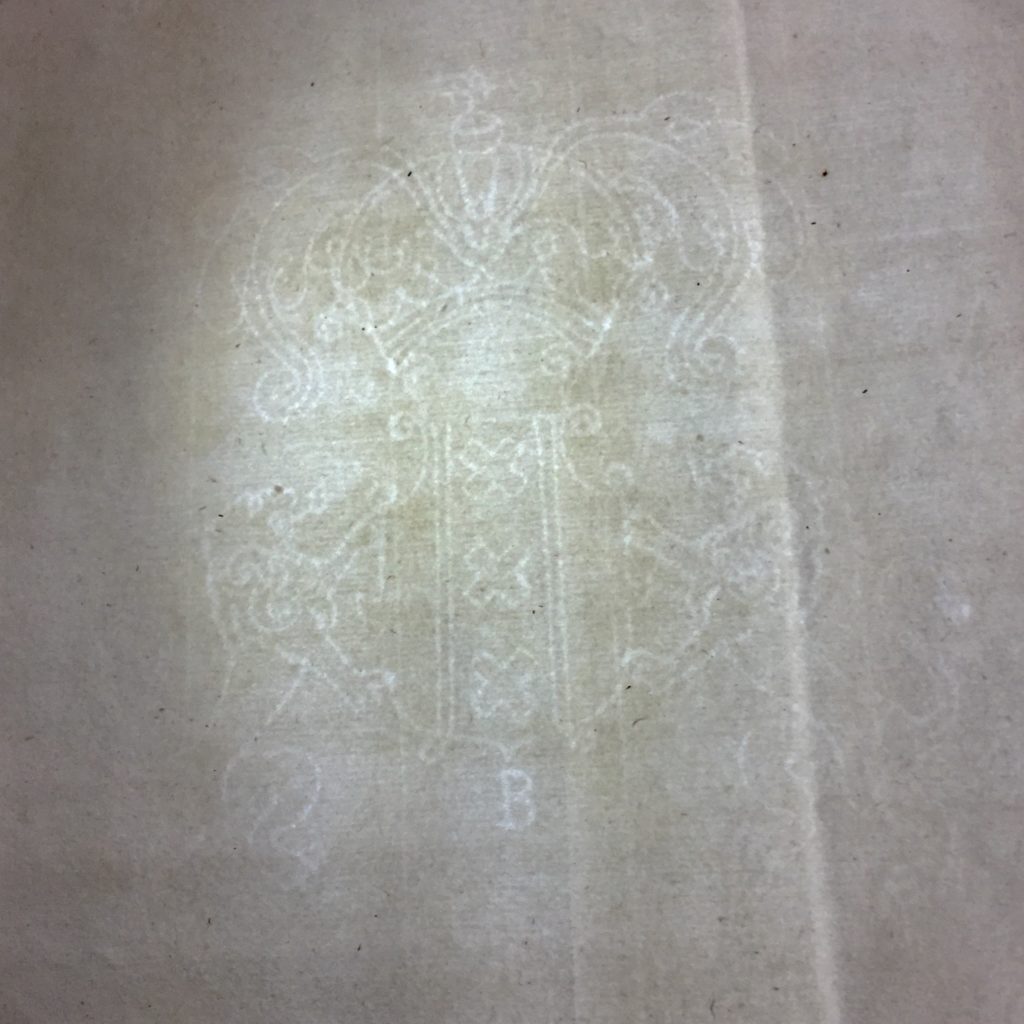

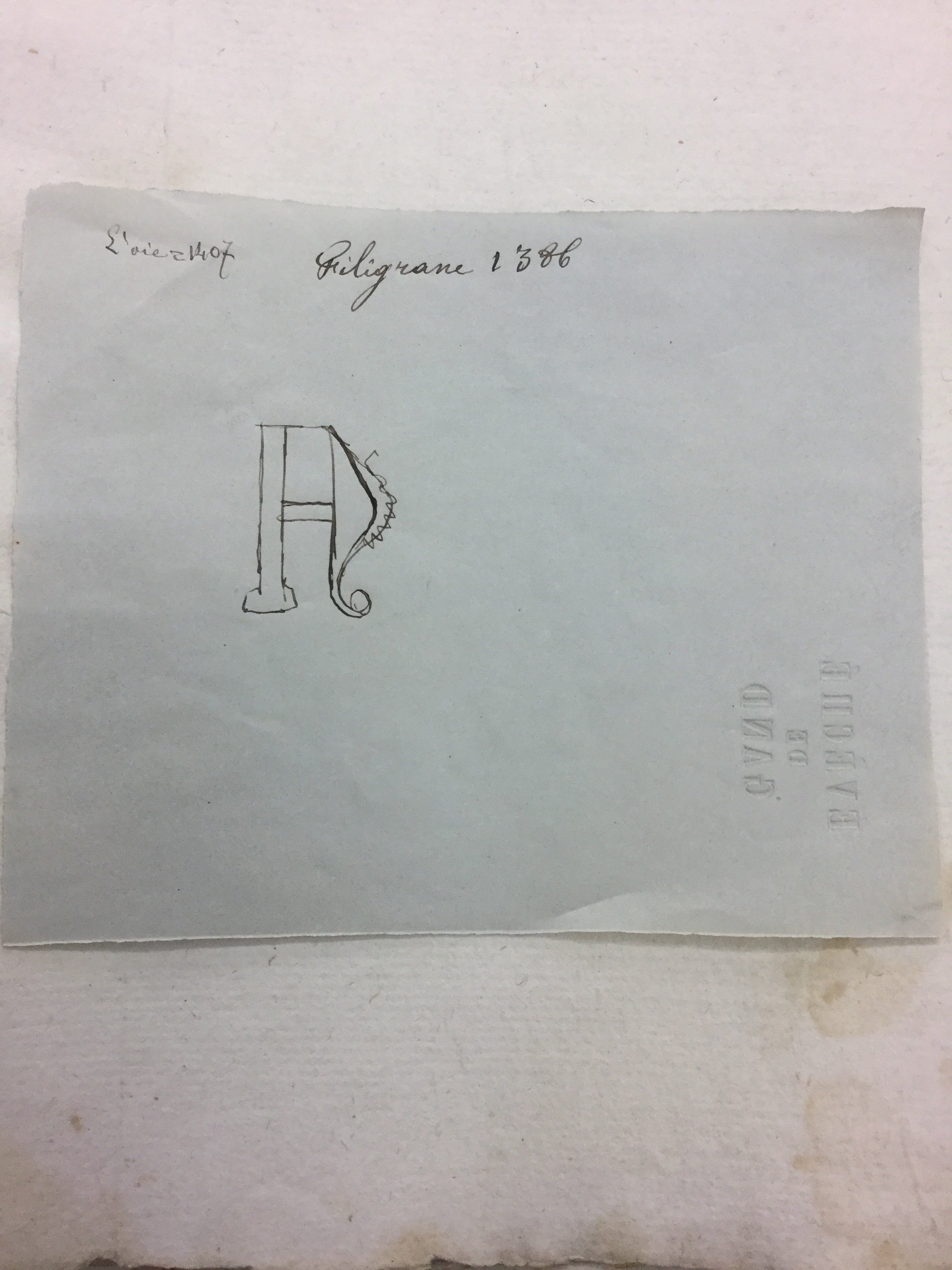

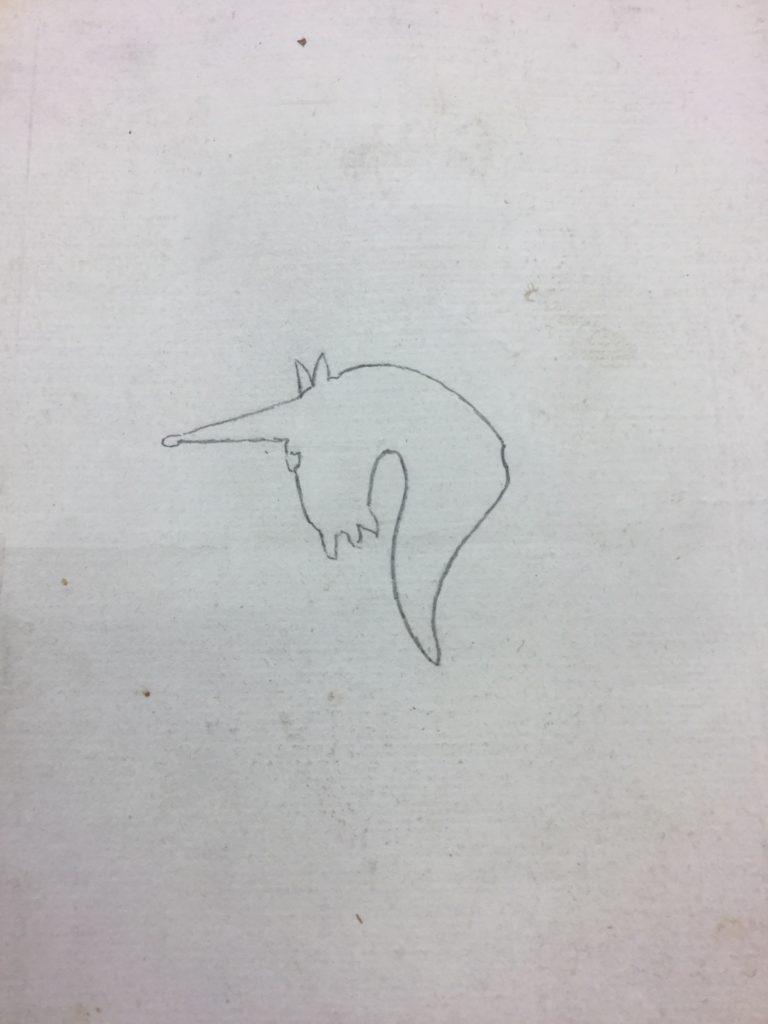

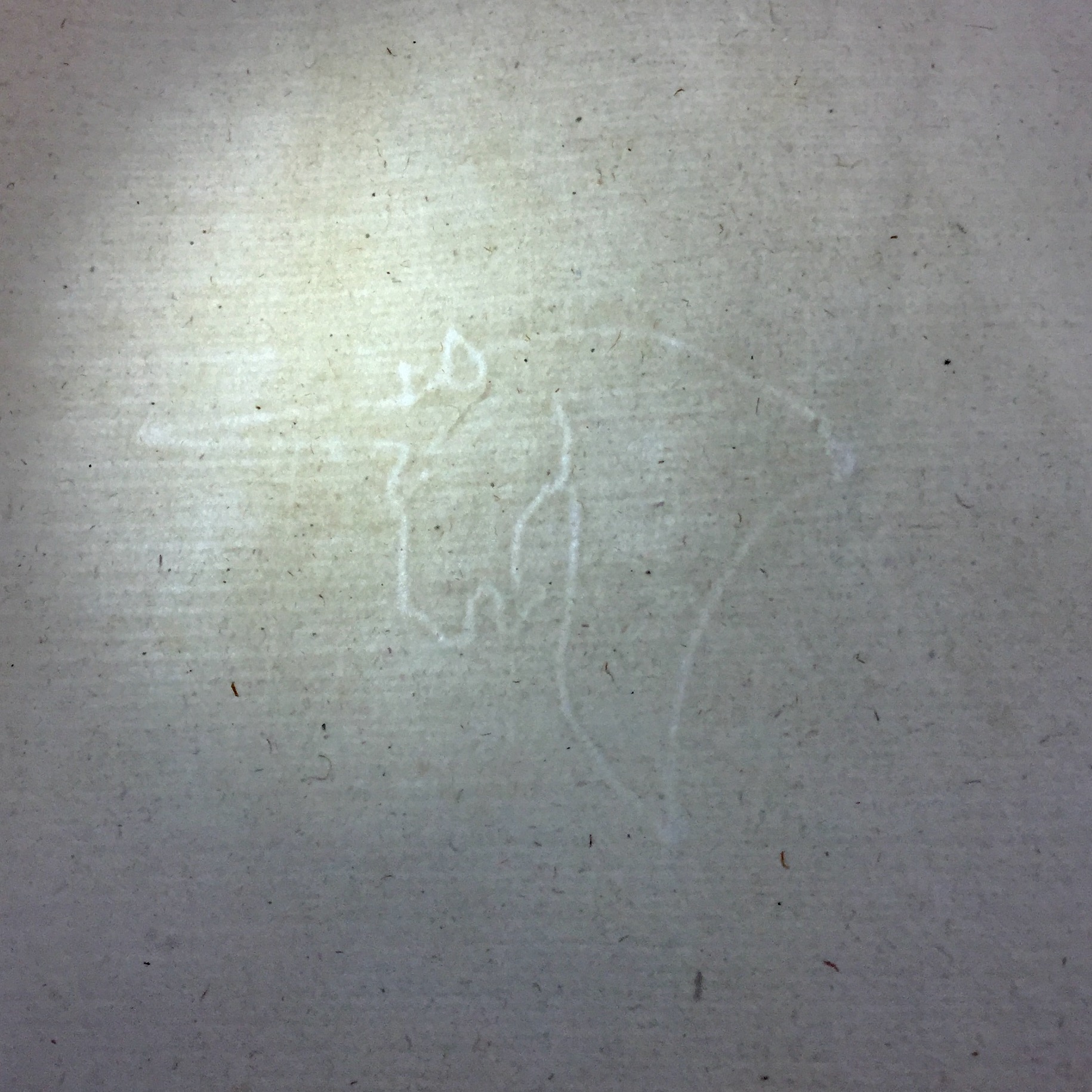

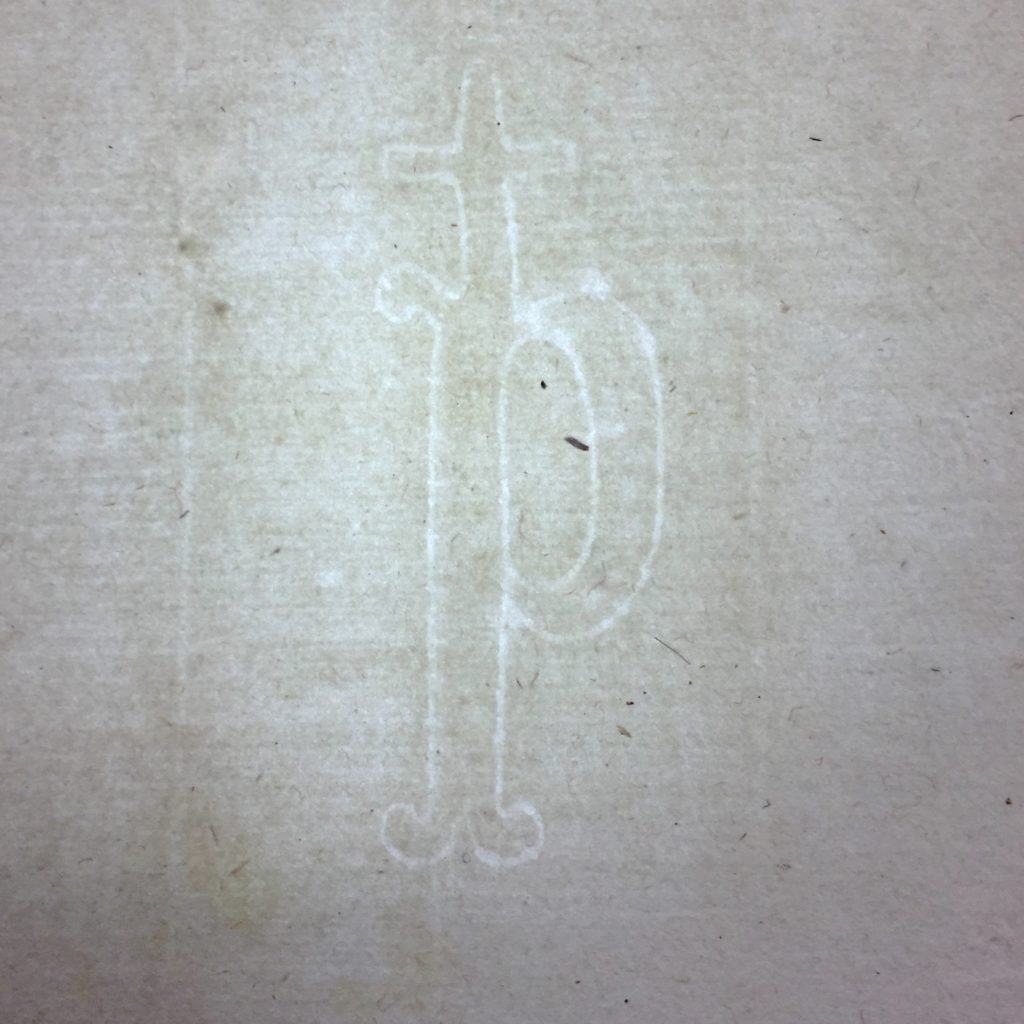

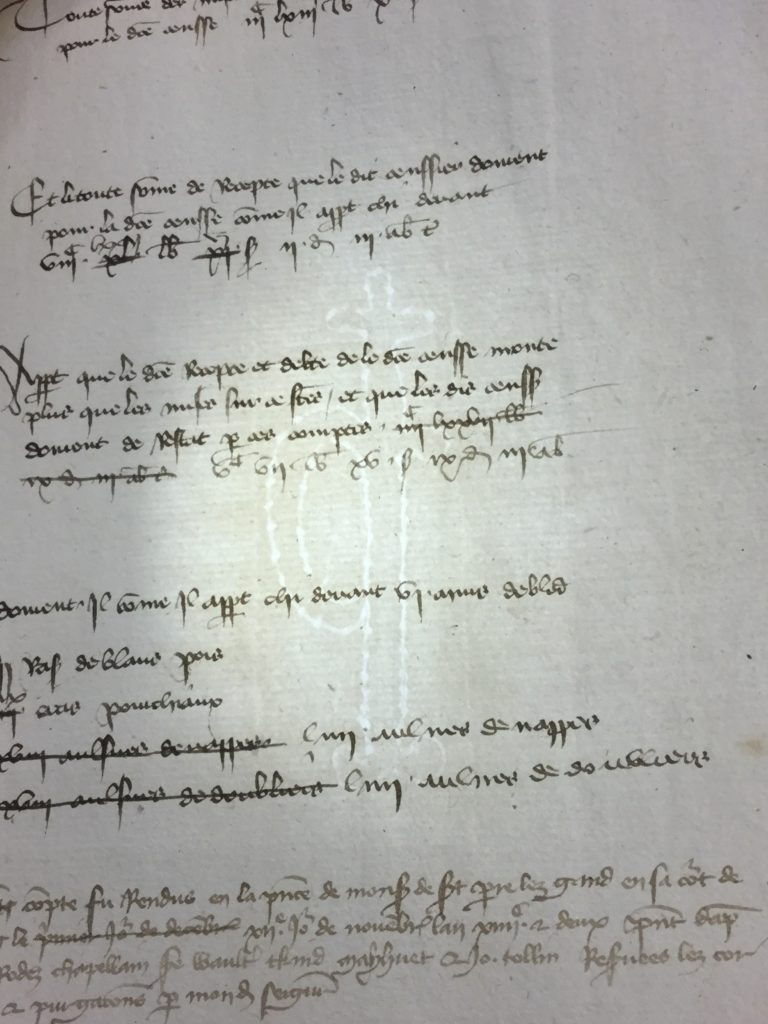

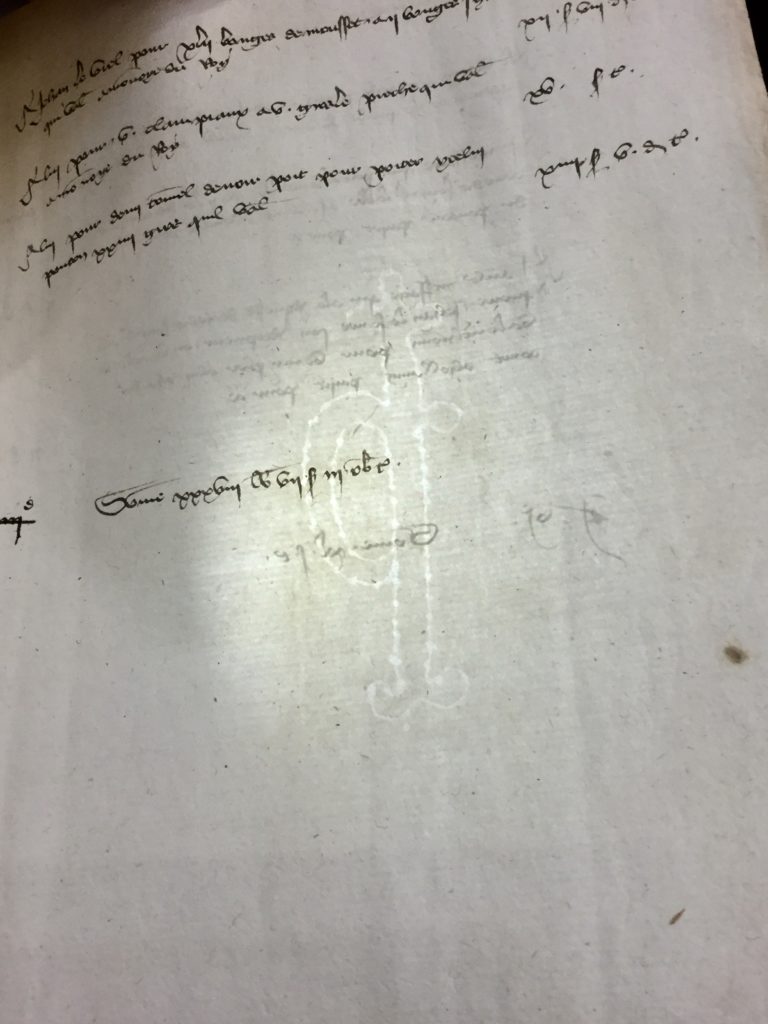

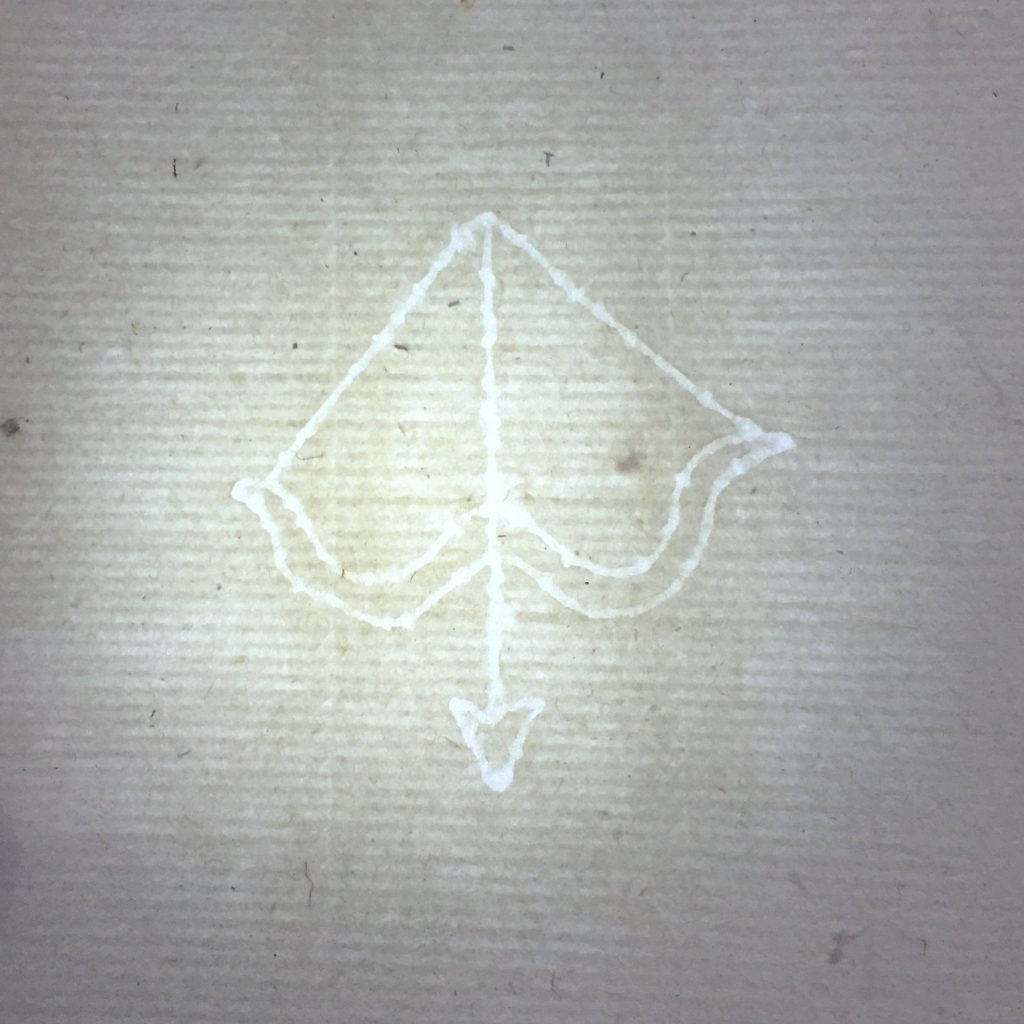

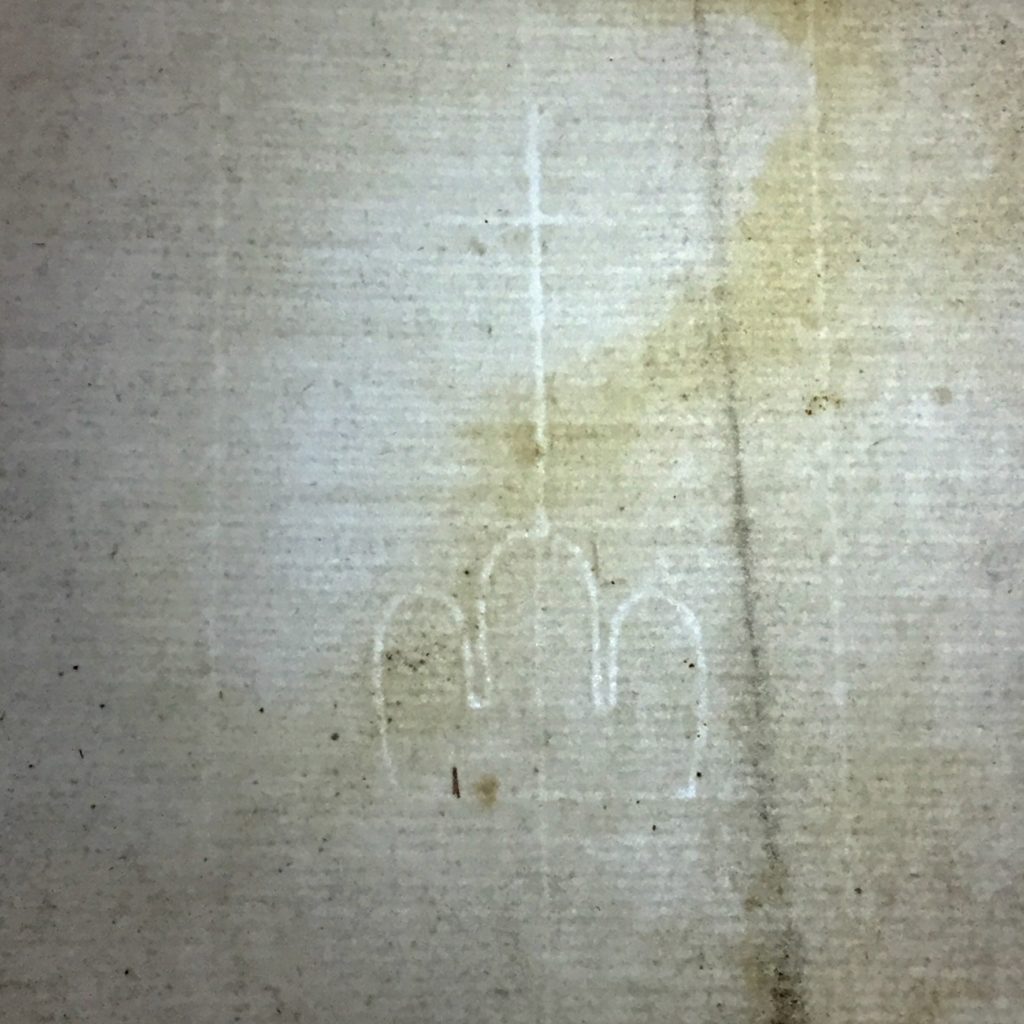

As one can see below, the watermarks have been impressed on the paper, with the top sheet having an outline of the watermark done in pencil, and later sheets having only the watermark itself.

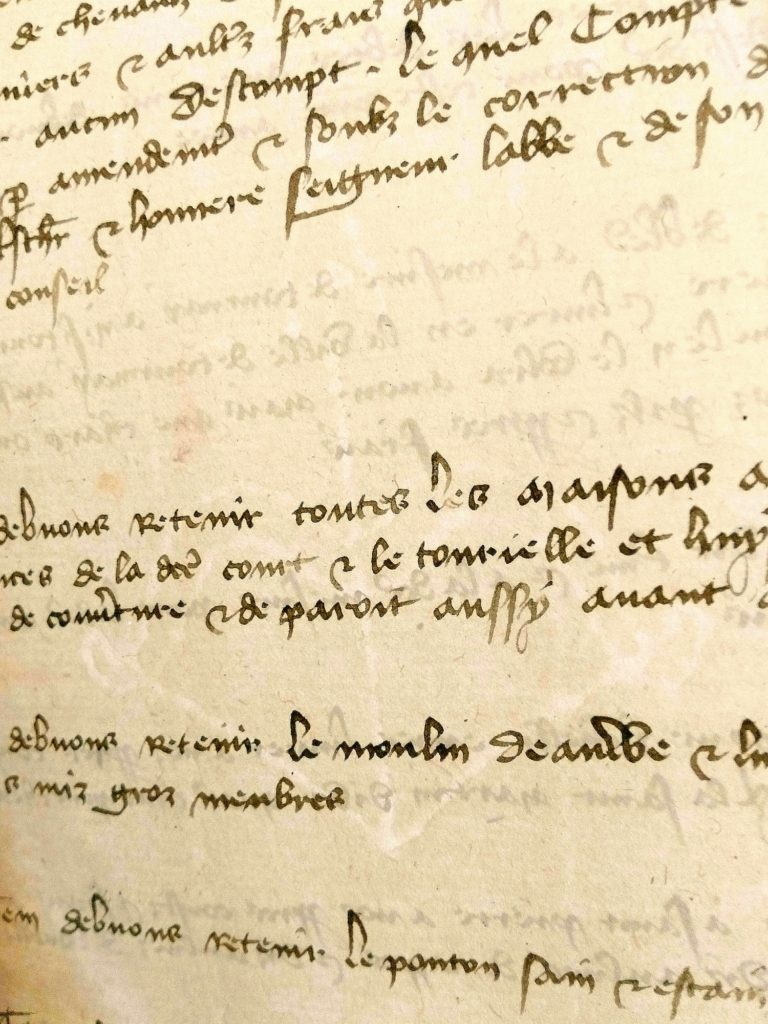

The archival inventory reads as if this collection of watermarks has been consistently compiled from the late fourteenth century by St. Bavo’s monks as a means to keep up with the numerous watermarks employed by the abbey. Instead, the collection is a later, early modern creation used a means of dating the watermarks used in earlier centuries. But how effective and accurate are these watermark dates? Thankfully for our purpose here, the manuscript K91 helps to answer this issue. K91 contains the yearly accounts of St. Bavo’s from the late 1300s to the late 1400s, allowing us to see how well these watermarks, dated by year, correspond to yearly entries in other documents from St. Bavo’s in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

Above, I have included the watermark for the year from 1480. It is the letter “P,” with a cross attached to the top of the letter and a bifurcated descender. According to the watermarking dating system of St. Bavo’s, this letter should only appear after 1480. However, in consulting the K91 account book (1384-1417), I found something quite different. The “P” first arises in the year 1402 of the accounts, a whole 78 years before it appears in the watermark compilation.

The clearest example is the “P” on the opening page of the account for the year 1403, the image K91 35r. just above. Perhaps this “P” is an exception? A dating oversight by the monks? In fact, it is the rule. Throughout the years for which account books survive, (1384-1417 & 1461-1498), very rarely do the accounts line up with the prescribed watermarks for that year. One watermark nearly hits the collection date, the watermark of 1395, the bow. The bow does not occur in 1395, but it does show up three years later in 1398, a much more reasonable margin of error.

The explanation for the inconsistency of the bow watermark is quite simple and known to many medievalists already. The monks of St. Bavo’s bought paper from a particular paper maker and they used that paper for many years. This is evident in the appearance of multiple watermarks in the same year of accounts (see the year 1403 in K91). The problematic example of the letter “P” presents a larger issue because the watermark appears far earlier than it should. It is not the only example of this phenomenon either- the watermark of 1410, a crown with a cross, first appears in the account books in 1407.

Based on the examples above, the efforts of the monks of St. Bavo’s were misguided in their attempt to coherently construct a means of dating their earlier documents. We know the monks were not papermakers themselves, so they did not have access to the wire frames with watermark outlines. These monks used their own watermarked documents to create their dating system, but they certainly did not rely upon the account books. If they had done so, they could not have drawn the conclusions they did. Perhaps they used a no-longer extant corpus of charters, but even in that case, the medieval monks of St. Bavo’s did not use watermarked paper in such a systematic and chronologically coherent way. They used the paper when they needed it- sometimes this was paper from decades earlier, sometimes this was new paper.

Further Reading-

Brown, Michelle P. Understanding Illuminated Manuscripts: A Guide to Technical Terms. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 1994.

Briquest Online- http://www.ksbm.oeaw.ac.at/_scripts/php/BR.php