by Sara Weber, Special Collections Digital Project Specialist, and Aedín Ní Bhróithe Clements, Irish Studies Librarian

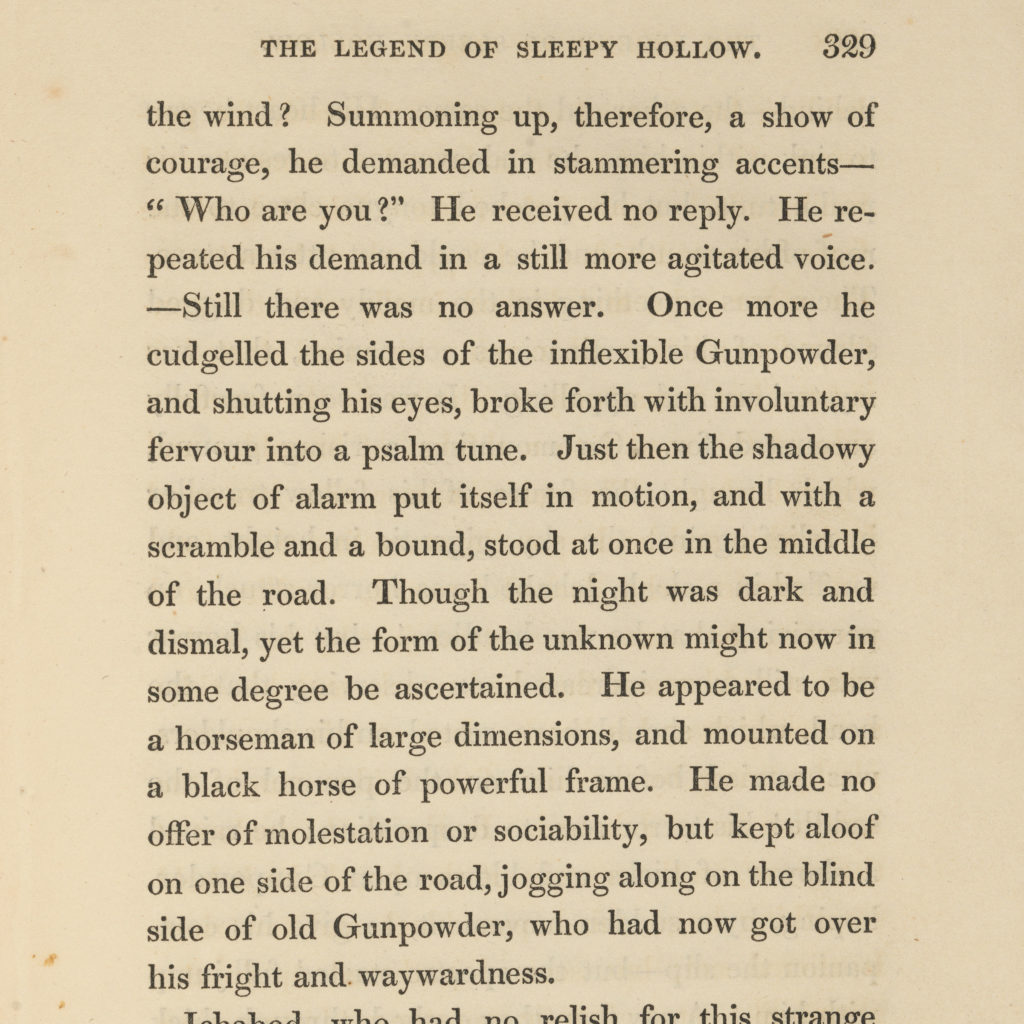

2019-2020 marks the two hundred years anniversary of Washington Irving’s first publication of The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent., which includes the perennial Halloween favorite “The Legend Of Sleepy Hollow”. In the time since its publication, the story has found its way into films, TV shows, other books, and various other popular culture references. In honor of the anniversary, we’ve selected it for our 2020 Halloween tale.

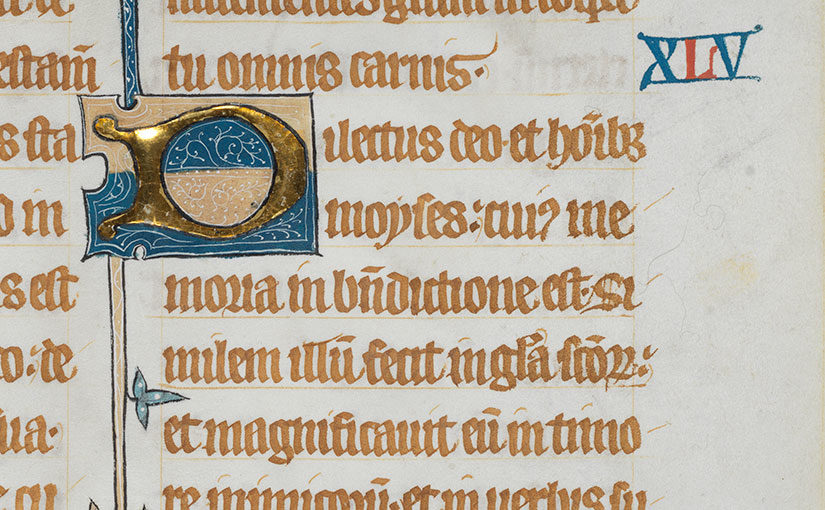

The particular volume shown in this post came to us across the ocean from Ireland. It was part of the library of Walter Sweetman, a nineteenth-century Catholic landowner in County Wexford. When the Sweetman family of South Dakota inherited the Irish property, all the books from the library were included with furniture, but many perished from exposure to the salt water. It’s a pity our conservators were not involved in organizing that shipment. We like to imagine a reader in a large Irish country house reading of Sleepy Hollow with the backdrop of an Irish stormy evening.

The Sweetman Collection, given to us in 1997, is a large collection of over 470 volumes.

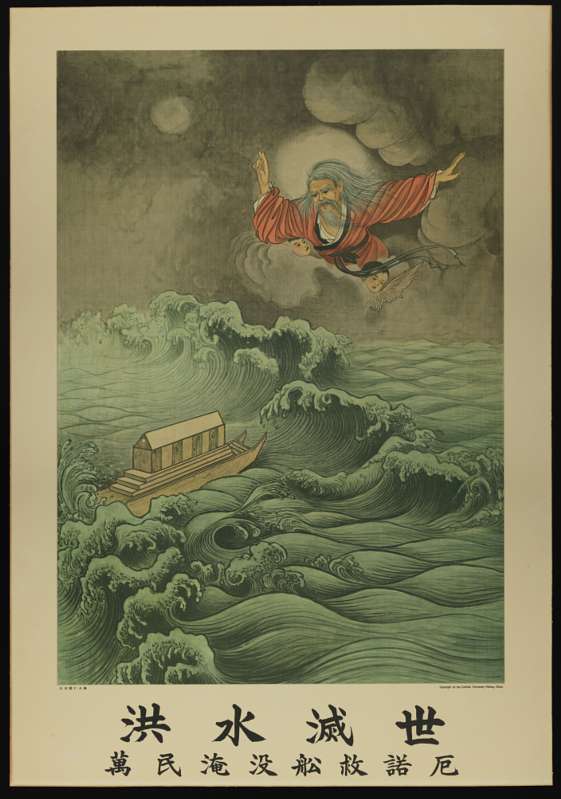

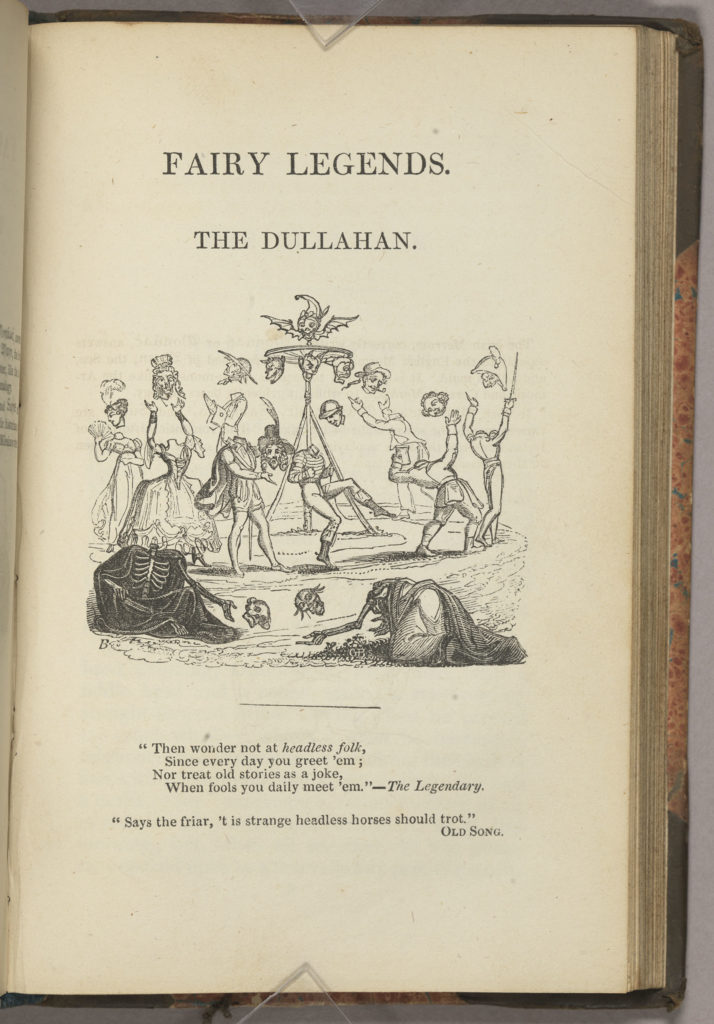

Irving’s headless horseman was not the first of his kind, however. Riders who have lost or carry their head appeared in various stories and folklore before featuring as Ichabod Crane’s nemesis, beginning as early as the 14th century poem Gawain and the Green Knight. In Irish legend, the Dullahan or dúlachán is a Grim Reaper-like rider who carries his head under his arm (sometimes also known as the Gan Ceann, meaning literally “without a head” in Irish). (See Jessica Traynor’s ‘How tales of the headless horseman came from Celtic mythology’ in the Irish Times, October 23, 2019.)

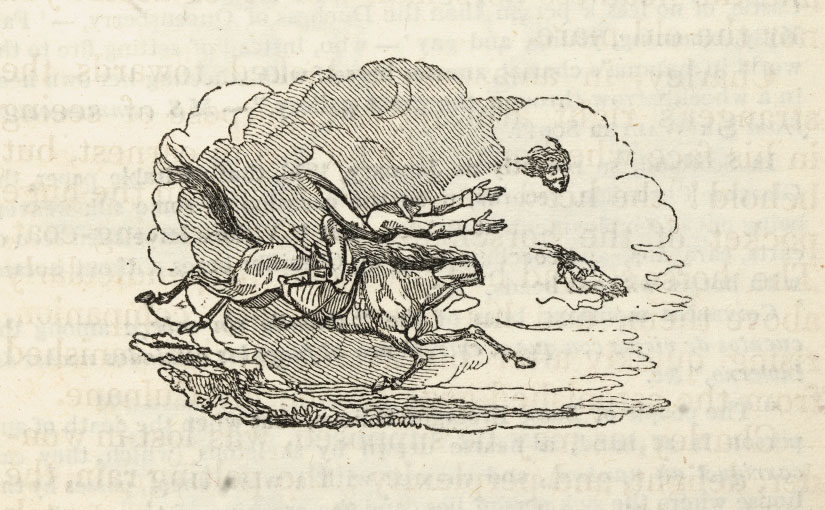

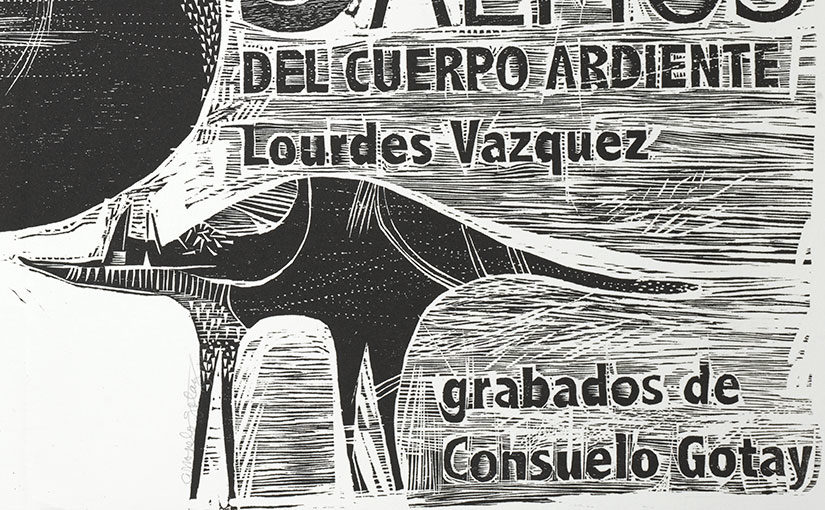

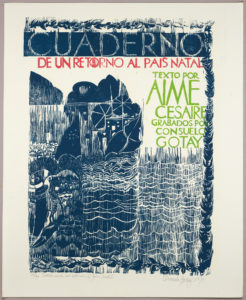

In Thomas Crofton Croker’s Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland (1834), we find several stories grouped together under the heading of “The Dullahan”, including one titled simply “The Headless Horseman”. Croker was one of the earliest writers to compile collections of Irish folklore. Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland was first published in 1825. Having received much attention, including translation by the Grimm brothers, Croker went on to produce two more volumes. This edition, published in 1834, is a one-volume selection that he edited. A summary of the controversy surrounding the various friends who contributed stories may be found in the biography by Maureen Murphy in the Dictionary of Irish Biography.

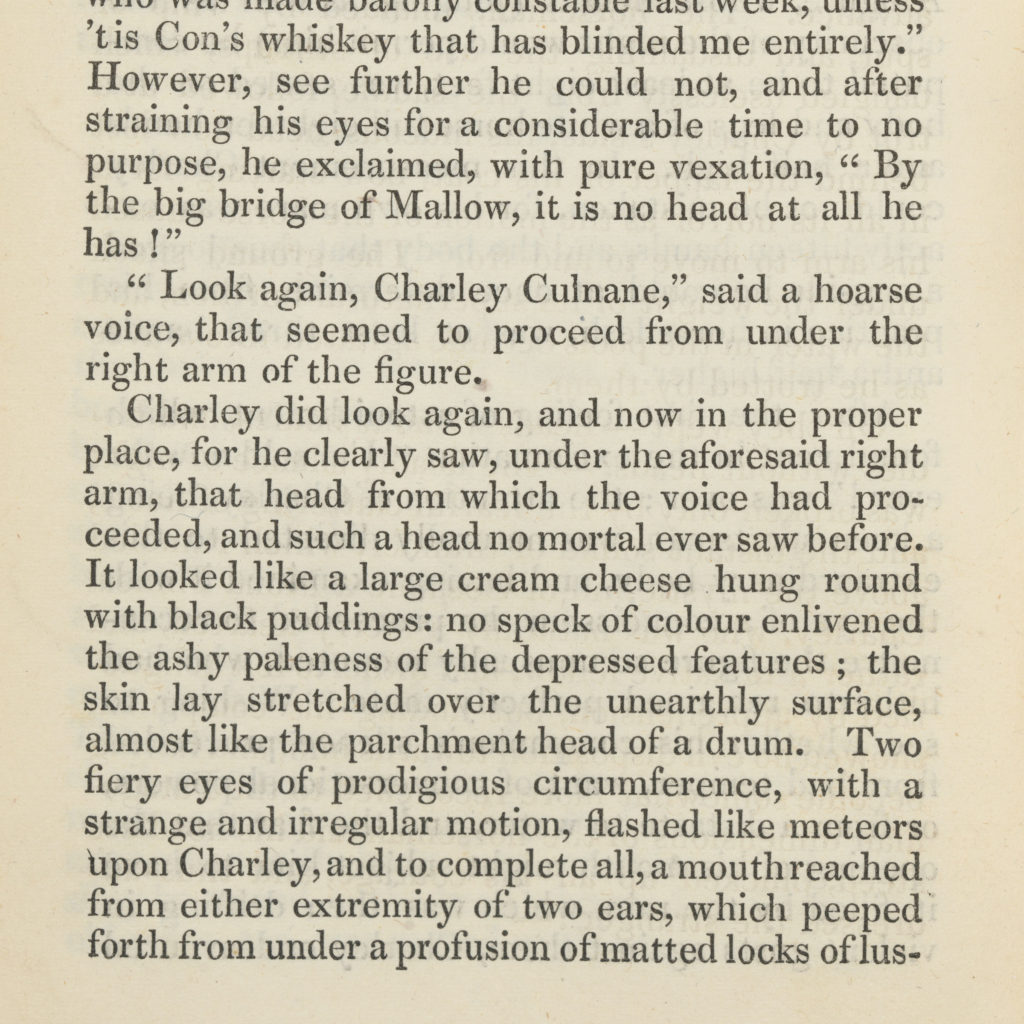

The humorous story that we have selected begins in a sheebeen in Ballyhooley, West Cork, and follows the incredible encounter of Charley Culnane with a headless man on a headless horse.

Happy Halloween to you and yours

from all of us in Notre Dame’s Special Collections!

Halloween 2016 RBSC post: Ghosts in the Stacks

Halloween 2017 RBSC post: A spooky story for Halloween: The Goblin Spider

Halloween 2018 RBSC post: A story for Halloween: “Johnson and Emily; or, The Faithful Ghost”

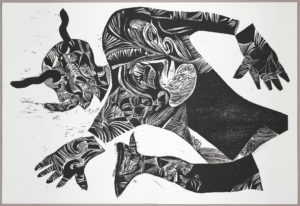

Halloween 2019 RBSC post: A Halloween trip to Mexico