by Rachel Bohlmann, American History Librarian and Curator

In honor of Juneteenth, the annual celebration of emancipation by African Americans following the Civil War, RBSC offers this new acquisition, a pamphlet by an African American minister who argued fervently during the late 1940s against states that restricted African Americans’ access to the polls. His message resonates today, as currently bills are rolling through state legislatures across the nation to regulate voting and reshape the franchise.

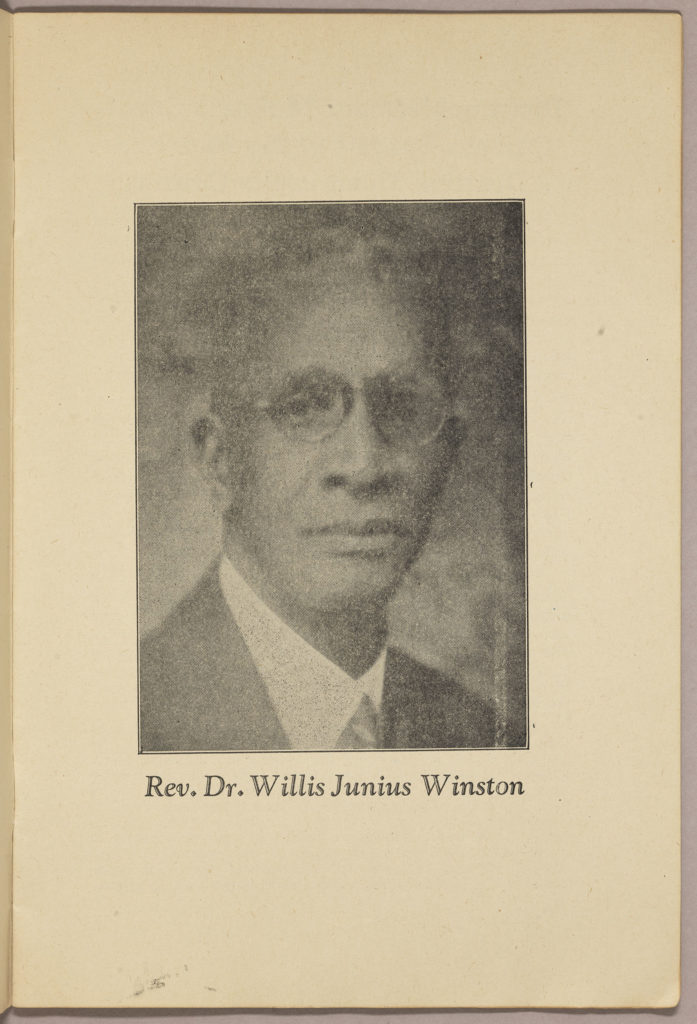

The Reverend Doctor Willis J. Winston (1877-1949) published this pamphlet, Disfranchisement Makes Subject Citizens Targets for the Mob and Disarms them in the Courts of Justice, sometime between 1947 and 1949. (The dates are inferred from references to aspects of the Truman Doctrine, introduced by the president in March 1947.) Winston was minister at the New Metropolitan Baptist Church in Baltimore, a position he had held since 1940 when the congregation formed. Before that he held a pulpit at the Wayland Baptist Church, also in Baltimore, from 1909. In the 1920s and 1930s Winston also served as president of two universities—Clayton-Williams University in Baltimore and Northern University in Long Branch, New Jersey.

Details earlier in his career as an outspoken leader for civil rights are scant but illuminating. In August 1932, a few months before the presidential election in which Franklin Delano Roosevelt defeated Herbert Hoover in the depths of the Great Depression, Winston gave the nominating speech for a fellow minister, Rev. Thomas S. Harten, at a mass meeting in Brooklyn sponsored by the Roosevelt for President Club. Harten ran as a Democrat for nomination as Congressman-at-Large for New York. (He did not gain the nomination.) By the time Winston denounced racial injustice in the late 1940s, however, he had become disillusioned with the Democratic party and urged his audience to remain within the “temple of Colored Republicanism” (p. 12) built by generations of African Americans.

By the late 1940s Winston’s disillusionment with FDR, Harry Truman, and the Democratic party was grounded in his experience with these administrations’ unfair racial policies. During the 1930s Roosevelt’s New Deal programs excluded most African Americans. After World War II, Truman was largely ineffectual in stemming a surge of violence targeted toward returning African American veterans, and he was indifferent to more general problems of segregation and disfranchisement. This pamphlet, which Winston probably developed out of a speech or sermon, was part of a rising tide of African American activism against racist attacks in the years immediately following the war that called on Truman to act.

Winston placed the responsibility to stop white violence against African Americans, specifically African American veterans, squarely on the federal government. “O, Federal Government, the Negro’s blood shall be required at your hand and shall be upon your head. This is the only country where men are tied to the stake and burned. . . . How long will this country’s flag fail to defend its defenders?” (p. 9)

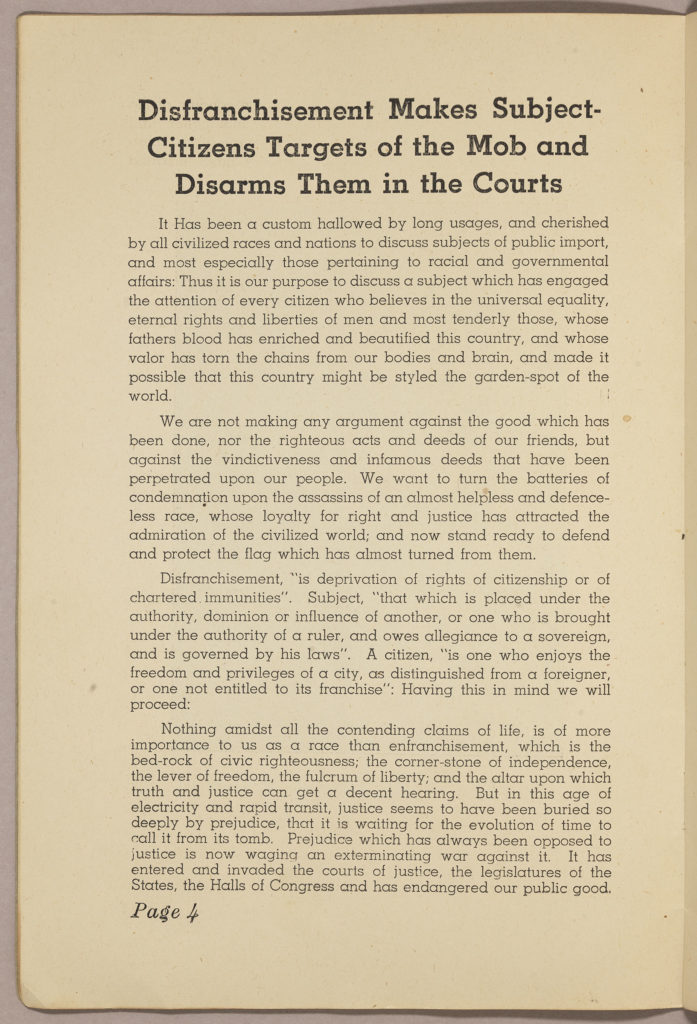

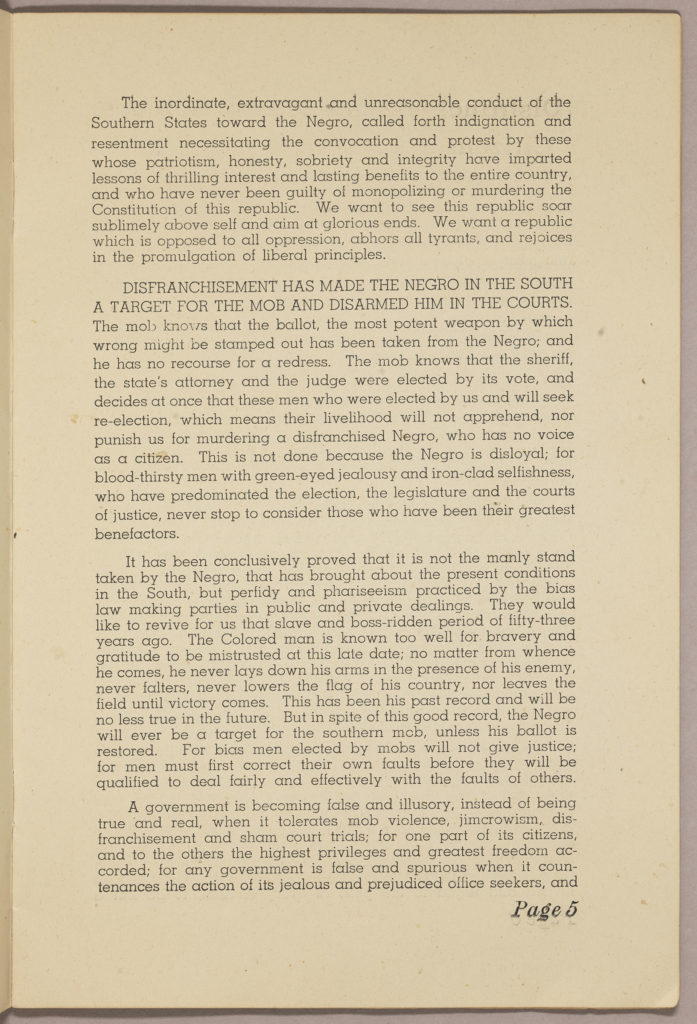

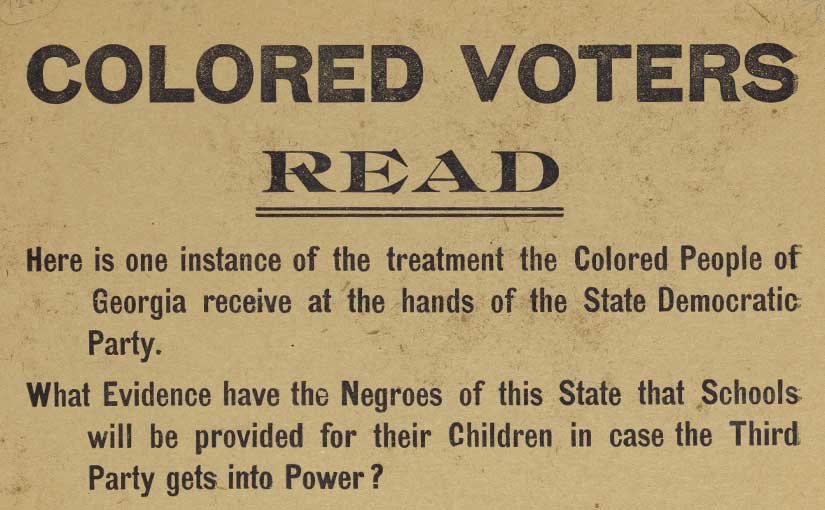

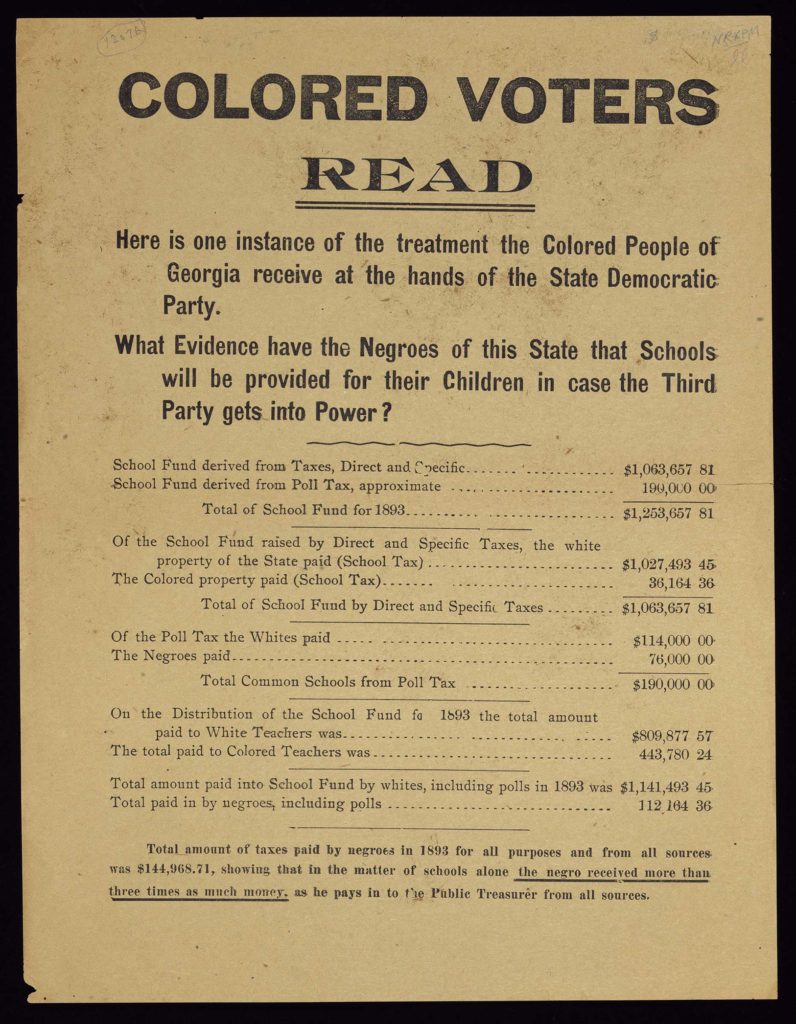

Winston focused on African Americans’ persistent lack of rights—their disfranchisement, exclusion from jury service, and prejudice from the bench—which he connected to economic and class prejudice, and to physical attacks against African Americans. “Disfranchisement,” Winston declared, “makes subject-citizens objects of scorn.” (p. 6) For example, “[w]e are denied the rights to sit as jury in the courts of nearly every State, enconsequence of which our person and property are subject, the former to every species of violence and insult, and the latter to fraud and spoilation without any redress.” (p. 8) The right to vote, he argued, must be restored to African Americans for their rights to be respected. “We are living in a country almost half slave and half free, and these barriers which have humiliated the race, and built walls of caste and class must be torn down, and the best way to tear them down, is with the ballot.” (p. 14)

By February 1948 Truman sent a list of civil rights recommendations to Congress— for strengthening the protection of civil rights, a congressional anti-lynching bill, an end to poll taxes, federal protection for voting in national elections, and an end to segregation—nearly all of the points Winston raised. Congress, however, took no action on these reforms. In response, Truman focused on a smaller, but significant goal to desegregate the military, which he successfully began later in 1948 by executive order. Winston dedicated his publication to his father, Philip Winston, a Virginian and a farm worker who probably never learned to read or write. The minister honored the sacrifices his father had made that allowed his son, as well as his other children, to become educated. Winston’s burial stone, raised by his congregation, students, and widow, likewise memorialized Winston for his character, kindness, and self-sacrifice.