Rare Books and Special Collections welcomes students, faculty, staff, researchers, and visitors back to campus for Fall ’24! We want to let you know about a variety of things to watch for in the coming semester.

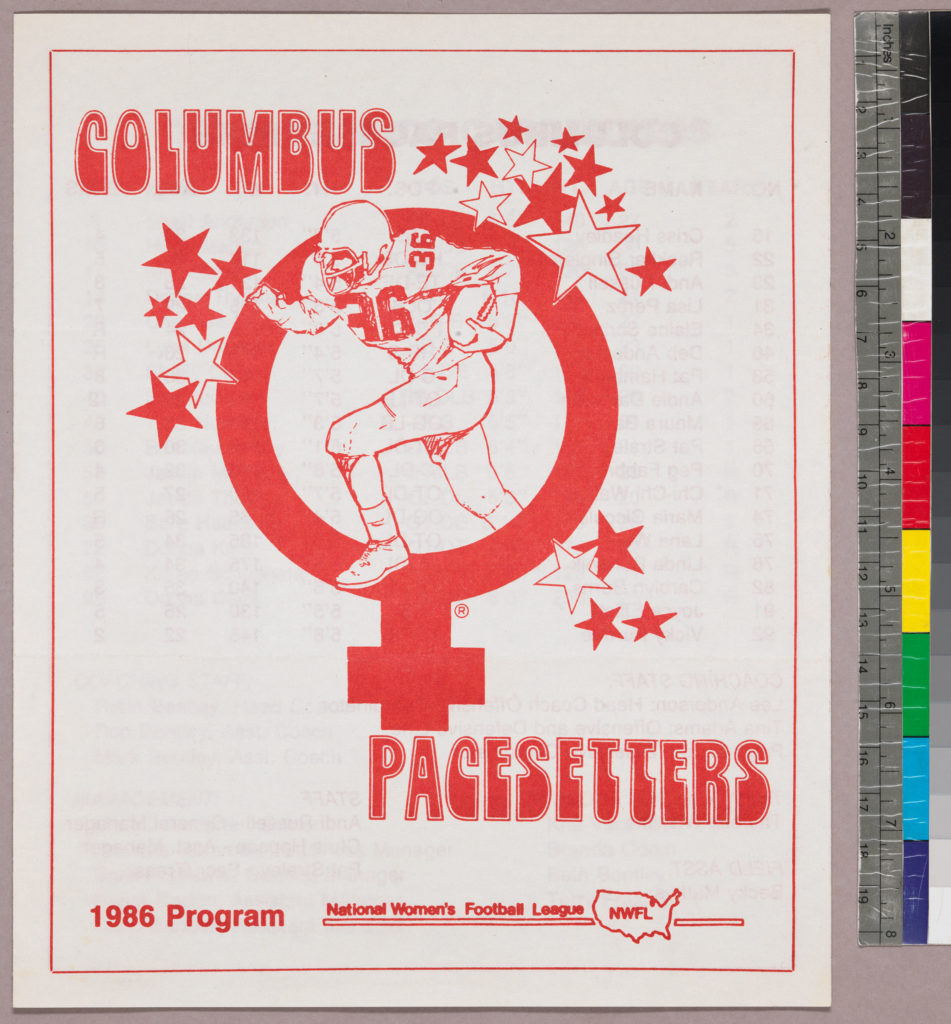

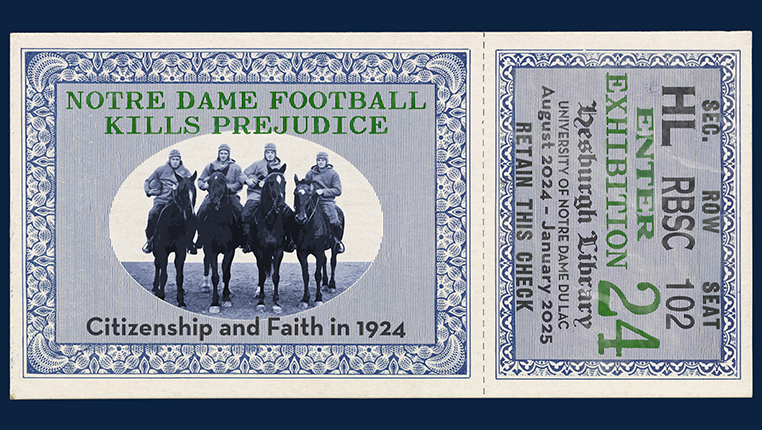

Fall 2024 Exhibition: Notre Dame Football Kills Prejudice: Citizenship and Faith in 1924

“Notre Dame football is a new crusade:

it kills prejudice and stimulates faith.”

— Rev. John F. O’Hara, C.S.C., Prefect of Religion,

Religious Bulletin, November 17, 1924

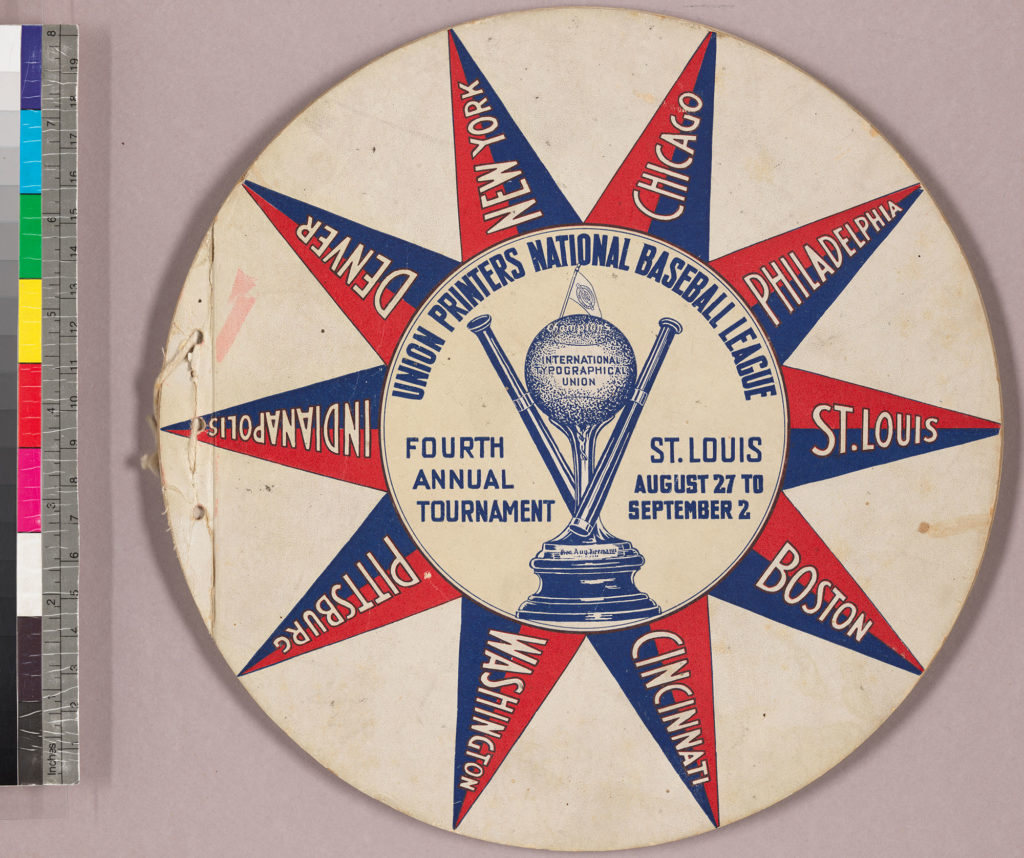

In the fall of 1924, the University of Notre Dame found great success on the football field and confronted a dangerous and divisive political moment. The undefeated Fighting Irish football team, cemented forever in national memory by Grantland Rice’s legendary “Four Horsemen” column, beat the best opponents from all regions of the country and won the Rose Bowl to claim a consensus national championship. Off the field, Notre Dame battled a reactionary nativist political environment that, in its most extreme manifestation, birthed the second version of the Ku Klux Klan. Sympathizers of this “100% Americanism” movement celebrated white, male, Protestant citizenship and attacked other groups—including Catholics and immigrants—who challenged this restrictive understanding of American identity.

In the national spotlight, Notre Dame leaders unabashedly embraced their Catholic identity. They consciously leveraged the unprecedented visibility and acclaim of the football team to promote—within the very real political constraints of the era—a more inclusive and welcoming standard of citizenship. Attracting a broad and diverse fan base, the 1924 national champion Fighting Irish discredited nativist politics and helped stake the claim of Notre Dame—and Catholics and immigrants—to full citizenship and undisputed Americanness.

Curators will host exhibit open houses on select Friday afternoons before Notre Dame home football games, including on September 6, September 27, and October 11. The drop-in open houses will run from 3:00–4:30 and will feature brief remarks by the curators at 3:30.

Other curator-led tours open to the public will be announced soon. Tours of the exhibit may be arranged for classes and other groups by contacting Greg Bond at gbond2@nd.edu.

This exhibition is curated by Gregory Bond (Curator of the Joyce Sports Research Collection, Rare Books and Special Collections) and Elizabeth Hogan (Senior Archivist for Photographs and Graphic Materials, University Archives).

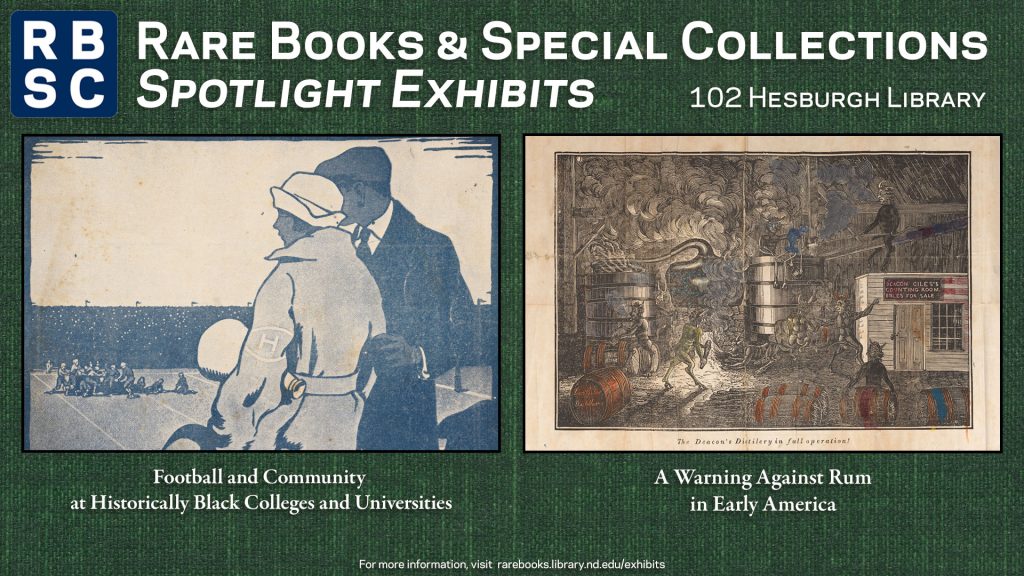

Stop in regularly to see our Collections Spotlights

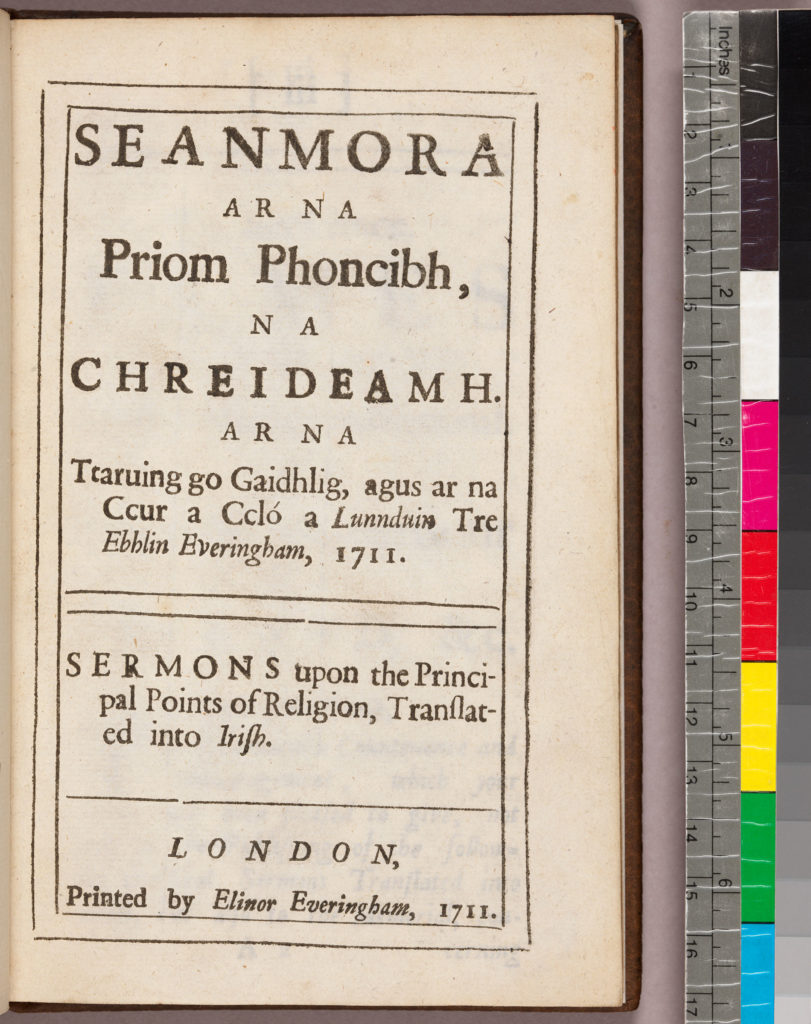

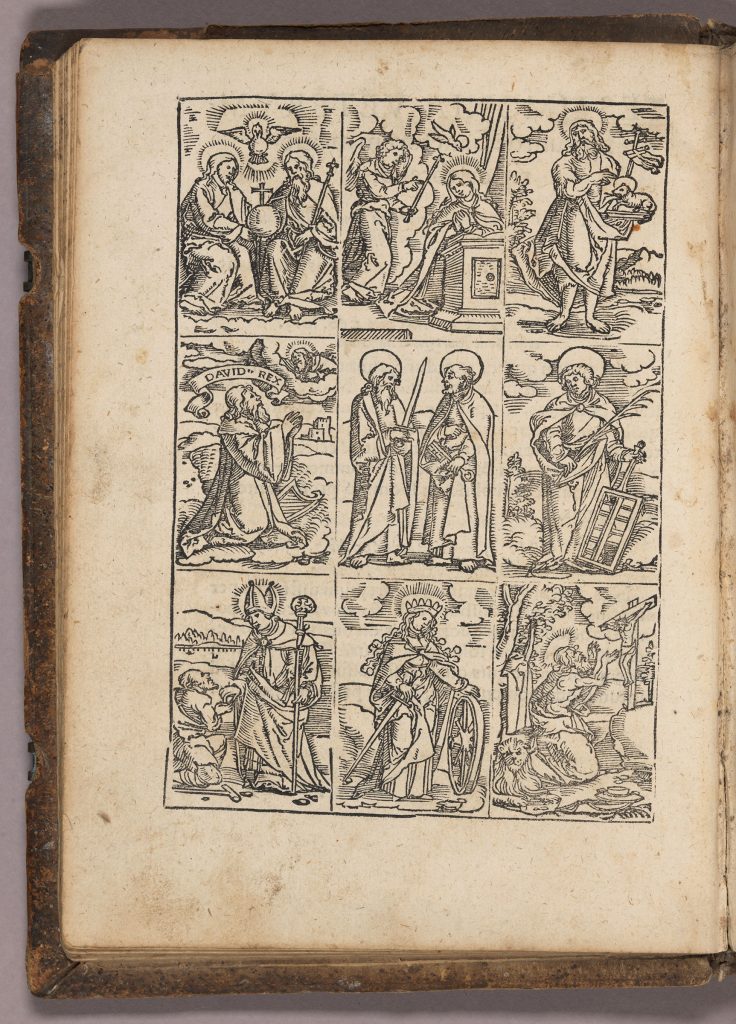

Currently on Display: Making Books Count: Early Modern Books in the History of Mathematics

Discover how books shaped science and our understanding of nature. The history of mathematics guides our understanding of astronomy, as revealed in works by Galileo, Copernicus, and others. Through ancient texts tracing the evolution of mathematical thought, visitors can explore the dialogue between mathematics and nature.

The last public spotlight tour is scheduled for August 28 at 1:30 pm.

This dual case spotlight is curated by Caterina Agostini (Indiana University Bloomington, Department of History and Philosophy of Science and Medicine). She previously served as a Postdoctoral Research Associate with the Reilly Center for Science, Technology, and Values and the Navari Family Center for Digital Scholarship. She is Co-PI in the Harriot Papers project.

Opening Soon: September Spotlights

RBSC spotlight exhibits will switch over for the fall during September. Two new exhibits will feature recently acquired editions of books by Mary Wollstonecraft and two manuscript fragments of French poetry. Stay tuned for more information!

These and other exhibits within the Hesburgh Libraries are generously supported by the McBrien Special Collections Endowment.

All exhibits are free and open to the public during business hours.

Special Collections’ Classes & Workshops

Throughout the semester, curators will lead instructional sessions related to our holdings to undergraduate and graduate students from Notre Dame, Saint Mary’s College, and Holy Cross College. Curators may also be available to show special collections materials to visiting classes, from preschool through adults. If you would like to arrange a group visit and class with a curator, please contact Special Collections.

Events

These programs are free and open to the public.

Thursday, October 3 at 5:00pm | The Fall 2024 Italian Research Seminar and Lectures will begin with a lecture by Giovanna Corazza (Università Ca’ Foscari), “Dante’s Chorographies: From the Territory to the Comedy.”

Learn more about Special Collections and other Hesburgh Library events, as well as other events in Italian Studies.

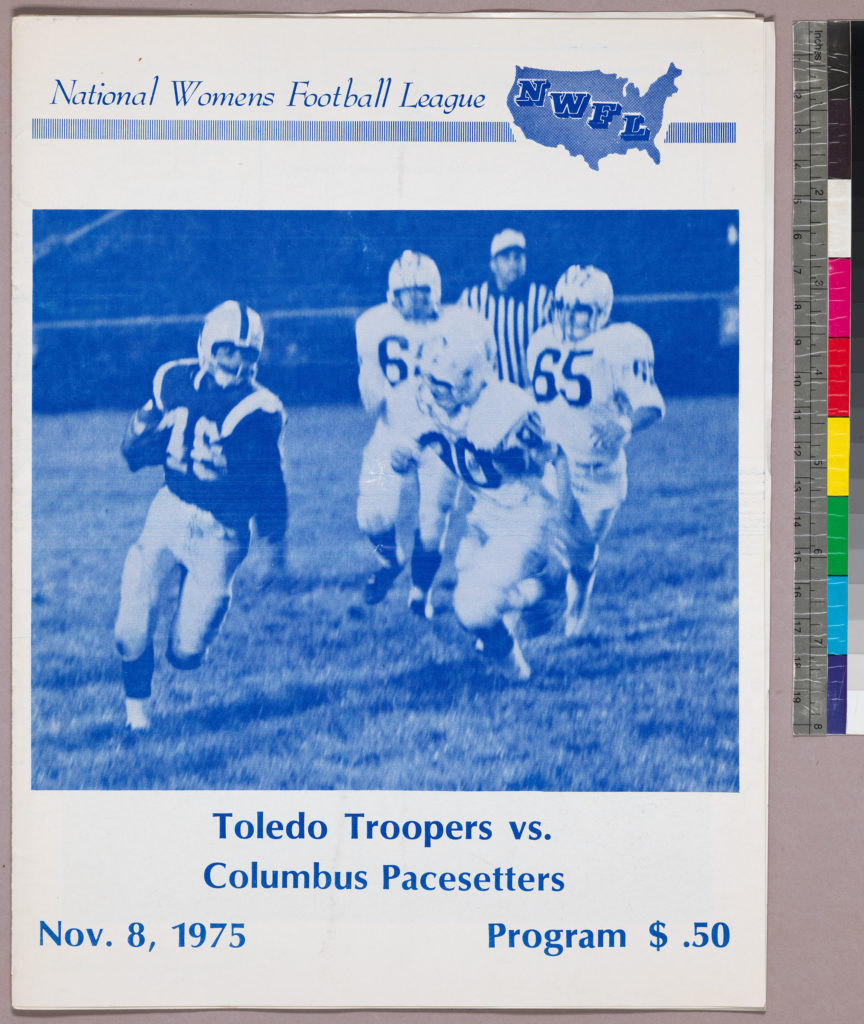

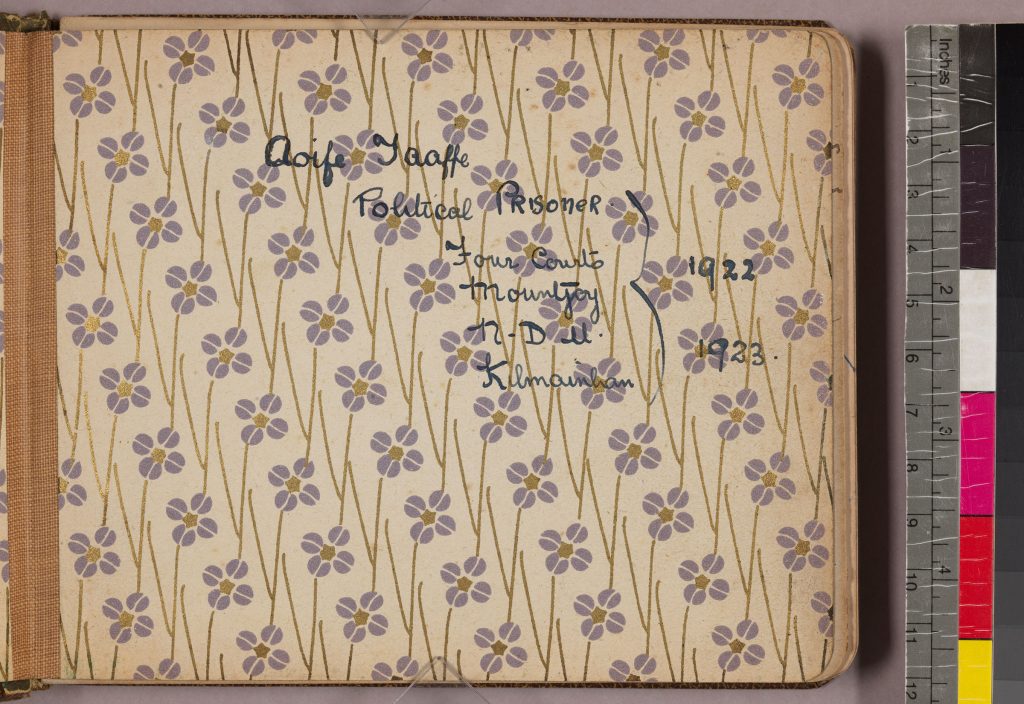

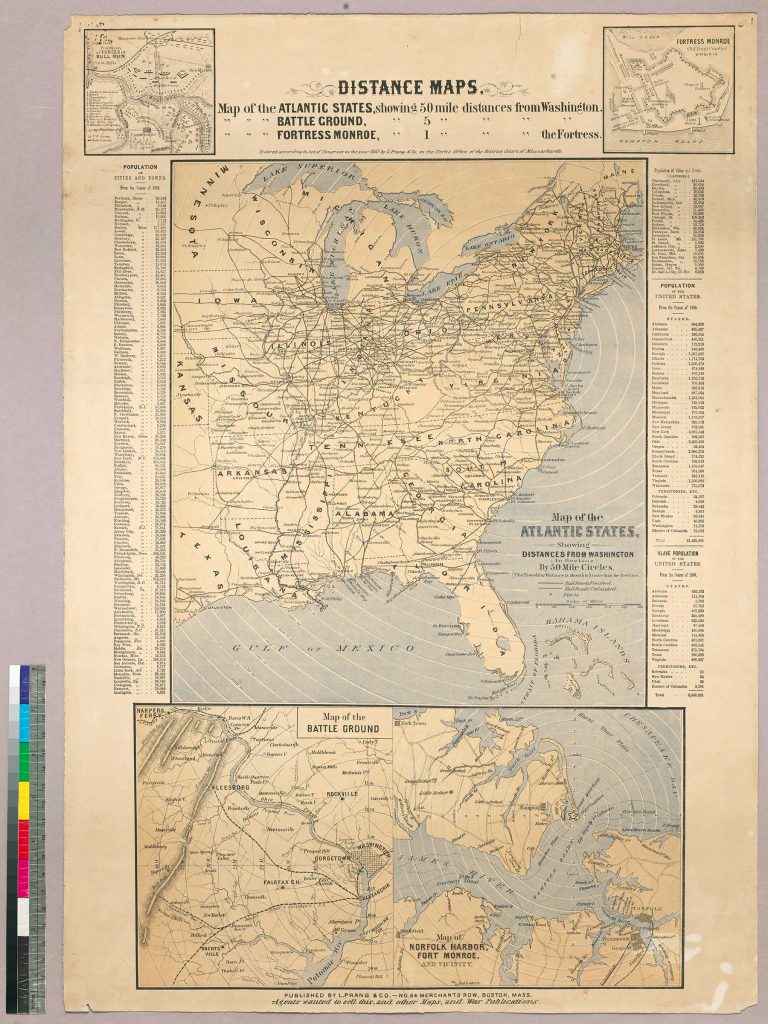

Recent Acquisitions

Special Collections acquires new material throughout the year. Watch this blog for information about recent acquisitions.

Anticipated Closures

Rare Books and Special Collections is regularly open 9:30am to 4:30pm, Monday through Friday. The department will be closed for the following holidays and events:

September 2, for Labor Day (Monday)

September 13, for Rev. Robert A. Dowd, C.S.C., Presidential Inauguration Events (Friday, afternoon only)

November 28-29, for Thanksgiving (Thursday and Friday)

Our last day open before the campus closure for Christmas Celebration will be December 20 (the Friday of final exams week).

Hours and other information for all Hesburgh Library locations can be found on the Library Website.