The tradition of dressing in costumes for Halloween is relatively recent, and regionally limited as well. Such costumes are not intended to convince anyone that they are genuine—no one is supposed to think the person dressing up is really a witch, a superhero, etc.—nor are they meant to be worn for more than an evening. No doubt much of the appeal of Halloween costumes is in how they allow us to playfully assume and express a new, temporary identity. In honor of Halloween, I’d like to consider medieval fables about animals who assume a new identity by “dressing up” as another species. These fables all attempt to promulgate the message that one’s identity cannot be changed, and that trying only leads to disaster. Read against the grain, however, such stories in fact reveal that human identity is unlike species difference—that our identities are mutable and contextual, and that this is a source of anxiety for those invested in social hierarchies.

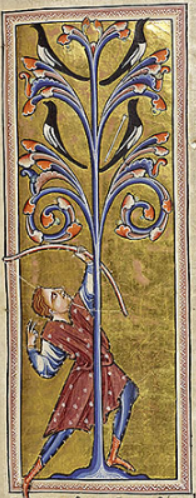

I can think of at least four fables where an animal uses another animal’s skin (or feathers) to represent themselves as a different species. These fables include The Ass and the Lion’s Skin (Perry Index 188/358); The Dog, the Wolf and the Ram (Perry Index 705); The Rook among the Peacocks (Perry Index 472); and The Wolf that Dressed in a Sheepskin (Perry Index 451). The animals’ motivations differ, but in attempting to take up their new role, they start to behave differently than before as well. In the first three fables mentioned, the disguised animal aims to represent themselves as “better” than they really are—stronger, more intimidating, more beautiful—and begins to not only look but act the part. By “dressing up” they are trying to move up as well, in a sense.

The donkey in The Ass and the Lion Skin runs around frightening other livestock in his lion pelt; the sheep in The Dog, the Wolf and the Ram dons the skin of his master’s deceased sheepdog and aggressively pursues the wolf who would harm his flockmates; and the rook adorns himself with peacock feathers and joins the peacocks, strutting around proudly. In The Wolf that Dressed in a Sheepskin (known in proverb form as the “wolf in sheep’s clothing”), the wolf’s intentions are more sinister, as he feigns harmlessness in order to insinuate himself amongst his would-be victims, before he is slaughtered for dinner by the unwitting shepherd. The other three fables conclude with the animals being recognized for what they “really” are, and then hurt or killed as a consequence.

The morals of these medieval fables often draw comparisons between species and social position, particularly class—you shouldn’t aim at too much upward mobility, or wish for what others have, lest it backfire, with you ending up in a worse position than before. For example, the moral to late medieval Scottish poet Robert Henryson’s version of The Dog, the Wolf and the Ram (The Wolf and the Wether) asserts:

Heir may thow se that riches of array

Will cause pure men presumpteous for to be;

Thay think thay hald of nane, be thay als gay,

Bot counterfute ane lord in all degre.

Out of thair cais in pryde thay clym sa hie

That thay forbeir thair better in na steid

Quhill sum man tit thair heillis ouer thair heid… (lines 2595–2601)

Thairfoir I counsell men of everilk stait

To knaw thame self and quhome thay suld forbeir,

And fall not with thair better in debait,

Suppois thay be als galland in thair geir:

It settis na seruand for to vphald weir,

Nor clym sa hie quhill he fall off the ledder:

Bot think vpon the wolf and on the wedder. (lines 2609–2616)1

Here you can see that rich attire will cause poor men to be arrogant; they think they have no superior, if they are dressed as fine, but they imitate a lord in every way. Out of their condition, in pride, they climb so high that they don’t refrain anywhere from injuring their superiors, until someone tips their heels over their heads…

Therefore, I advise men of every rank to know themselves and whom they should refrain from injuring, and fall not into contention with their superior, even if they are as stylish in their dress: it suits no servant to keep up strife, nor to climb so high that he falls off the ladder: just think of the wolf and of the wether.

The narrator’s “counsell” did not just reflect a private opinion. From 1429/30, James I had imposed sumptuary legislation in Scotland, which limited expensive textiles such as silks and some kinds of furs to upper social strata.2 Such legislation was not exclusive to late medieval Scotland, but could be found in many regions across the world, through the eighteenth century.3 “In the case of medieval and early modern Europe,” says historian Lorraine Daston, “over a period of five hundred years (c. 1200–1800), these regulations not only failed to stamp out excess (or what might now be called conspicuous consumption), they arguably exacerbated the very ills they were meant to remedy.” In other words, not only did people not abide by these regulations, the regulations themselves could spur a sort of sartorial “arms race,” inspiring clothesmakers to come up with novel extravagances that were not yet forbidden,4 and consumers to keep up with the newest fashions.

Clothing can visually signify so many aspects of identity (such as class, gender, occupation, religion, and political affiliations), yet the details are inconstant over time and from one place to the next, and clothing can easily be taken on and off. The abovementioned fables, admonitory as they are, express unease with the instability of human social categories as expressed through clothing. Fables often map social hierarchy onto species, and in doing so, they suggest that there is something “natural,” something immutable, about these hierarchies—that a poor man and a lord are as distinct from one another as a sheep and a dog, or a rook and a peacock. But if these hierarchies were really so natural and immutable, the fables wouldn’t have cautionary morals that tell people not to “forget their place.” There would be no need for the admonition, just as there would be no impetus to create (and update) sumptuary regulations, were it not for people constantly breaking boundaries in their fashion choices.

Linnet Heald

PhD in Medieval Studies

University of Notre Dame

- Denton Fox, ed., The Poems of Robert Henryson (Clarendon Press, 1981), pp. 96–7. Modern English translations are my own. ↩︎

- Maria Hayward, “‘Outlandish Superfluities’: Luxury and Clothing in Scottish and English Sumptuary Law from the Fourteenth through the Seventeenth Century,” in The Right to Dress: Sumptuary Laws in a Global Perspective, c. 1200–1800, ed. Giorgio Riello and Ulinka Rublack (Cambridge University Press, 2019), p. 97. ↩︎

- For a global history of sumptuary legislation, see The Right to Dress: Sumptuary Laws in a Global Perspective, c. 1200–1800, ed. Giorgio Riello and Ulinka Rublack. ↩︎

- Lorraine Daston, Rules: A Short History of What We Live By (Princeton University Press, 2022), p. 156. ↩︎