Beowulf is historically known for its “digressions” into extratextual storytelling, and scholars have regarded these intrusions as everything from evidence of Beowulf’s oral origin to a demonstration of the problematic structure of the poem. My interpretation of this narrative interlace understands the various stories as directly engaged with the main subject of the plot by providing parallel circumstances that highlight important aspects of the main narrative centered on Beowulf and monster-slaying.

Much ink has been spilled on the Sigemund and Heremod episodes. Some read these stories as foils of each other with Sigemund representing a positive model for Beowulf to follow and Heremod representing a negative model that serves as a warning for the young hero. However, Mark Griffith has demonstrated how even the Sigemund episode is coded with misdeeds, and he has suggested that many of the details included in the story portray the hero rather pejoratively.

There are numerous other “digressions” within Beowulf, though these two have traditionally gained the lion’s share of attention in the scholarship. Today, I want to look closely at the form and possible narrative function of the Hildeburh episode (1076-1159), frequently called the Finn episode, which follows directly after the two previously referenced stories, and the three serve as entertainment during the celebration following Grendel’s defeat and Beowulf’s triumph.

While the first two “digressions” seem to parallel aspects of Beowulf’s own character, the episode centered on Hildeburh conveys a very different message, and I would argue, perhaps to a specific audience. While the first two stories focus on heroes who possess great strength, the third story centers on something only hinted at thus far in the poem: maternal loss.

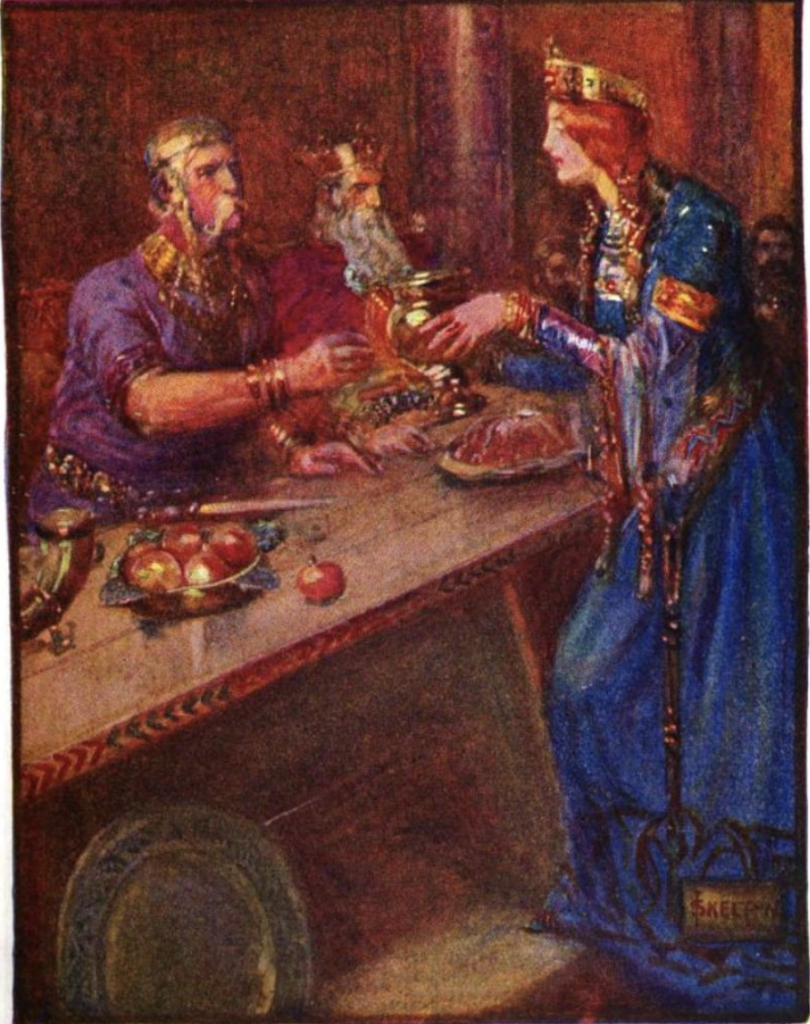

Just prior to the celebratory storytelling in Heorot, we learn that Wealhðeow, queen of the Danes, advises her husband, King Hroðgar, to place his trust in his nephew and kinsman Hroðulf rather than investing in a foreign hero, like Beowulf. Thomas Shippey has noted the irony in this as earlier in the poem there is reference to the burning of Heorot, which is perpetrated by Hroðulf and results in the murder of both of Hroðgar’s sons and Hroðulf’s usurpation. These enigmatic references to a future Danish power struggle might easily be missed, but they nevertheless frame Wealhðeow as a mother who will lose her sons to violence and kin-slaying, possibly within the broader context of a feud between rival brothers for the throne. After all, Hroðgar is not the first in line, and he even remarks of his late (and elder) brother Heorogar—deep in his cups—that se wæs betera ðonne ic “he was better than I” (469) presumably referring to his prior kingship.

Indeed, the need for Hroðgar to build Heorot at all suggests that the former Danish mead hall is no longer around, which invites further questions such as whether its destruction was a result of inter-family violence and Hroðgar’s overthrow of his older brother to claim the Danish crown. Alas, the poem does not tell.

Although the Hildeburh episode concludes the celebration of Beowulf’s victory over Grendel, its mood is far from jovial. The tale relates a feud between the Danes and the Frisians and Hildeburh is caught in the middle. Hildeburh’s song relates how her bearn ond broðor “sons and brothers” (1074) find themselves on opposite sides of a feud where everybody dies in the ensuing conflict—everyone loses—all of them die in the violence. Indeed, Hildeburh’s role as Danish princess made Frisian queen herself—a failed freoðuwebbe “peace-weaver” (1942) is highlighted by the mutual deaths of her family members. The feud takes both Finnes eaferan “the heirs of Finn” (1068) and hæleð Healfdena “heroes of the half-Danes”(1069) as the parallel descriptions of how wig ealle fornam (1080) “war took all” and lig ealle forswealg “fire swallowed all” (1122) connects warfare with their shared cremation next to one another on the funeral pyre.

Hildeburh metodsceaft bemearn “bemoaned her fate” (1077) because she has no way to avenge her kinsmen. She is on both sides and therefore on neither. No matter what happens in the ongoing feud between her peoples, Hildeburh will suffer loss. And again, a mother loses her sons. Moreover, her tale parallels the foreshadowed fate of Wealhðeow’s sons, who will be betrayed by her treacherous nephew Hroðulf (1180-7).

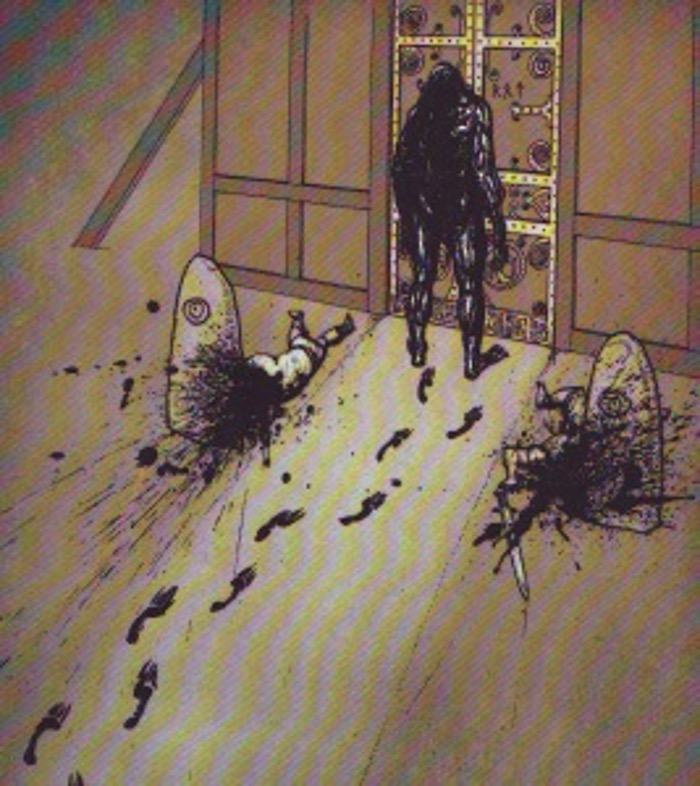

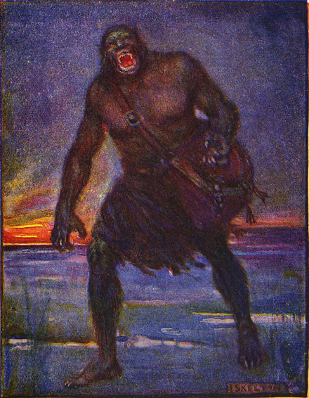

As I discuss in much greater depth in my dissertation subchapter “The Ethical Paradox of Grendel’s Mother’s Revenge” (358-370), it is this contextual framework within which Grendel’s mother appears in the narrative (out of nowhere) as a wrecend “avenger” to wreak vengeance upon those who murdered her son. In a sense, Grendel’s mother does—and is able to do—what Hildeburh cannot. And, as Leslie Lockett and others have observed, Grendel’s mother’s actions represent a legally and ethically “fair” exchange: a life for a life. This engenders further sympathy for her character’s suffering and retaliation, especially following directly after the context established by Hildeburh episode.

Even after Grendel’s mother is slain, the pattern repeats. Not long after we meet Queen Hygd in Geatland, her son is killed in a feud with the Swedish king Onela, leaving Beowulf to inherit the throne. Yet another mother loses her son to a feud, underscoring the narrator’s comments on the violence between the Danes and the Grendelkin: ne wæs þæt gewrixle til,/ þæt hie on ba healfa bicgan scoldon/ freonda feorum “that was not a good exchange, that they on both sides should pay with the lives of kinsmen” (1304-06).

We do not know who wrote Beowulf, and probably never will. Nevertheless, at this point in the poem, I am reminded of Virginia Woolf’s argument in A Room Of One’s Own: “I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman.” While I am not arguing for a female author of the poem (though why not), I would contend that there seem to be strong rhetorical appeals directed at women—especially mothers—within Beowulf, which suggest that they were likely part of the poem’s anticipated audience.

Richard Fahey

PhD in English

University of Notre Dame

Further Reading

Bonjour, Adrien. The Digressions in Beowulf. Basil Blackwell. 1950.

Fahey, Richard. “Enigmatic Design and Psychomachic Monstrosity in Beowulf.” University of Notre Dame: Dissertation, 2020.

—. “The Lay of Sigemund.” Medieval Studies Research Blog. Medieval Institute: University of Notre Dame (March 22, 2019).

Fell, Christine. Women in Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1984.

Franzen, Eleanor. “Peace, Politics, Gender and God: Beowulf and the Women Of Early Medieval Europe.” Bluestocking: Online Journal for Women’s History (October 6, 2011).

Gardner, Jennifer Michelle. “The Peace Weaver: Wealhtheow in Beowulf.” Western Carolina University: Master’s Thesis, 2006.

Griffith, Mark. “Some Difficulties in Beowulf, Lines 874-902: Sigemund Reconsidered.” Anglo-Saxon England 24 (1995): 11-41.

Kaske, Robert. “The Sigemund-Heremod and Hama-Hygelac Passages in Beowulf.” Publications of the Modern Language Association 74 (1959): 489-94.

Lockett, Leslie. “The Role of Grendel’s Arm in Feud, Law, and the Narrative Strategy of Beowulf.” In Latin Learning and English Lore: Studies in Anglo-Saxon Literature for Michael Lapidge (I), edited by Katherine O’Brien O’Keeffe and Andy Orchard, 368-88. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2005.

McLemore, Emily. “Grendel’s Mother Eats Man, Woman Inherits the Epic: Why Women Should Continue Teaching Beowulf.” Medieval Studies Research Blog. Medieval Institute: University of Notre Dame (April 28, 2021).

Overing, Gillian. Language, Sign and Gender in Beowulf. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1990.

Shippey, Thomas A. “The Ironic Background.” In Interpretations of Beowulf: A Critical Anthology, edited by Robert D. Fulk, 194-205. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1991.