Reviewer #1: This is an important article. Although the topic is quite specialized, the application of a methodology normally applied to the Middle Ages to a neglected early modern topic is a useful tool for further investigation of less documented subjects.

Reviewer #2: The author’s argument is unoriginal and uninteresting. There is room for a retelling of the story, but this piece of writing is not it.

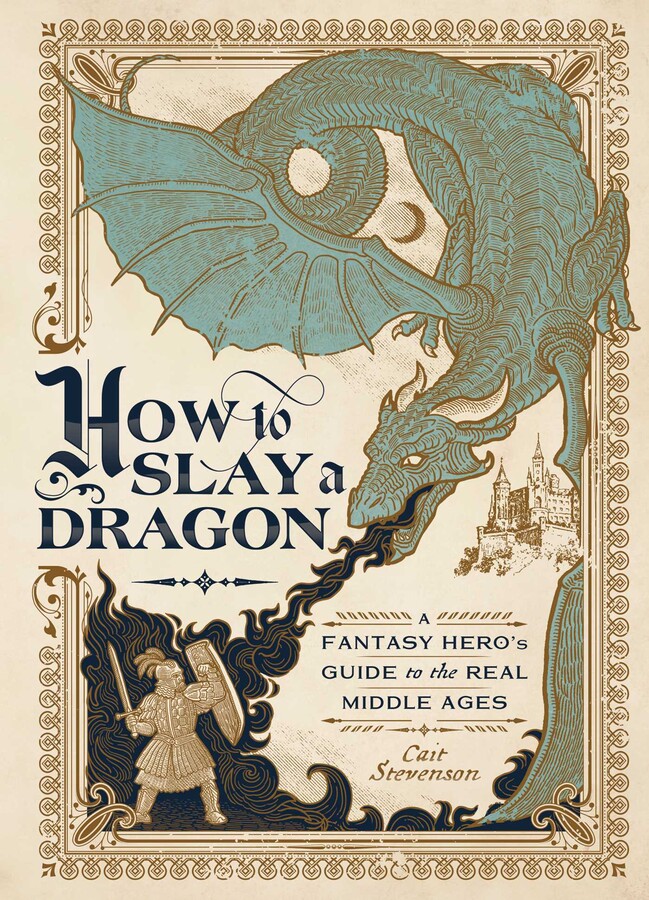

As medievalists, our scholarship and self-esteem are to a large extent governed by Reviewer #2. Or rather, they are shaped by an entrenched system of abstracts, standardized book proposals, peer review, impostor syndrome, and desperate self-scrutiny in hopes of avoiding that Reviewer #2. In the course of writing a medieval history book aimed at a popular market, however, I (and my self-esteem) fell headlong into a rather different process. After my earlier post concerning my book, How to Slay a Dragon: A Fantasy Hero’s Guide to the Real Middle Ages (Tiller Press, 2021), some readers expressed interest in hearing more about the process of producing a pop history book.

A small disclaimer: I cannot adequately compare the scholarly and popular processes, unfortunately, because I am currently working on my first academic book proposal, also unfortunately. Nevertheless, I hope that my experience can prove helpful and even hopeful—if I can make it through this process, so can you.

The Ambush(es)

Relieved that academic conferences might be dwindling in the Zoom era? I was actually approached by a representative from Tiller Press (a Simon & Schuster imprint) after an in-person conference panel on Internet public history. It was not an open-ended conversation, however: she had a specific book for me to write, a coffee-table volume on people of color in medieval Europe. Since everyone wants to write that book right now, I was eager to set up a later meeting to discuss the possibility.

I decided in the meantime that such a book really needed to be written by a junior scholar of color, and I am white, so I thought the meeting was going to be short. Instead, now was the time the editors on the other end of the call asked me what I would like to write. Sure, I have plenty of ideas—but I did not have a practiced elevator pitch for any of them. I stammered out several, and miraculously, they jumped on A Fantasy Hero’s Guide to the Real Middle Ages.

Well, “jumped on” meaning I would have to prove the viability with a book proposal.

The Book Proposal

Fortunately for us, this bears some similarity to the academic version, except with a far stronger focus on potential sales. The publisher wanted:

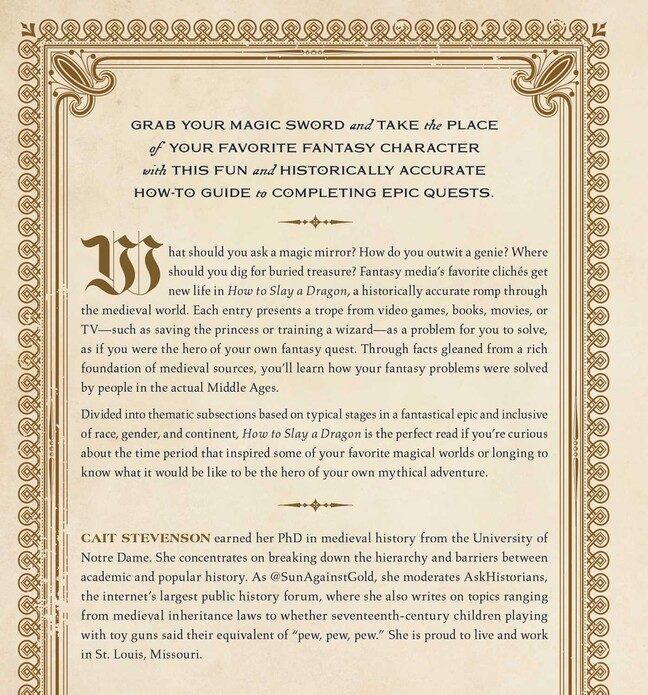

1. A short abstract: a 1-2 sentence publicity blurb to entice readers quickly.

2. A long abstract: 250ish words in which to:

(a) describe the premise in more depth

(b) explain that the book would be based on proper primary and secondary sources

(c) present the desirable “P crossed with Q crossed with R” description of the contents (in my case, “Rejected Princesses meets Lords of the Rings meets TV Tropes”)

(d) set out the probable audience

(e) justify its current relevance (its gender- and race-inclusiveness, in light of Internet discussions)

(f) finish with an “awesomeness” factor (“How to Slay a Dragon reveals a Middle Ages far more outrageous than any fantasy fiction could hope to be.”)

3. An author profile

4. A projected outline

5. Multiple sample chapters

Fun fact: only one of my three sample chapters made it into the book.

Don’t Panic

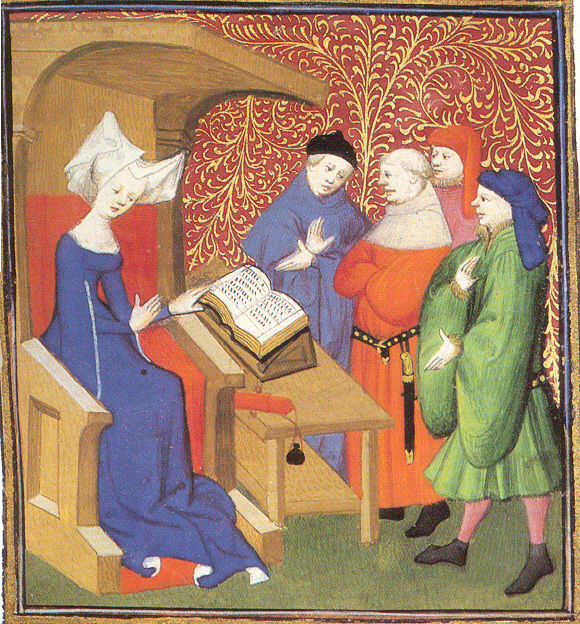

This was—and remains—the hardest part for me. If you think you struggle with impostor syndrome when submitting an article, imagine how it feels when your contract mentions royalty shares from the potential sale of audiobook rights and other people being hired to write a sequel. I know to say that may sound like I’m bragging, but trust me, all I feel inside are knots around my heart and maybe a little nausea. So please be aware before you start the process of writing and publishing a pop history book: it’s not a matter of “pick a manuscript illumination to plop on the cover, contact the archive, and get the rights.” Your editor is going to mention “cover art” and “hiring an illustrator,” and your job is to not panic.

I was not good at this.

Writing and Editing

Rather than deliver a full book and then revise it wholesale, my editor (the wonderful Ronnie Alvaredo) required me to work in pieces. The nature of my premise means my book has around forty short chapters, and she set up a schedule for me to submit three new ones or three revised ones at a time. She also asked me to start with a few chapters that I thought might make good advance chapters to show the sales team and potential corporate buyers. No pressure! So I was always revising other chapters as I was writing new ones.

Another important factor for medievalists to keep in mind is that we are the experts, not the editorial team—not just in terms of information, but in terms of how medieval as a field works. I lost count of how many times I had to explain, “We simply don’t know exact dates or a location and also the author’s name is probably a pseudonym.”

The Best Part

There is no Reviewer #2.

The Worst Part

That means you have to be your own.

Cait Stevenson

PhD in Medieval Studies

University of Notre Dame