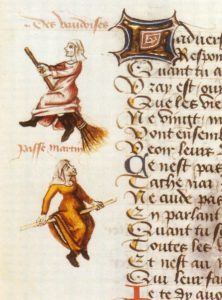

With Witch ranked the most popular costume nationwide, Frightgeist reports, “There’s a frighteningly high chance you will see a Witch costume on Halloween this year” – and these costumes will likely share some similarities. Asked to describe the physical features of a witch, we tend to list tropic characteristics like those returned through a Google search: she is old and ugly with a hooked nose and green or otherwise sallow skin. First and foremost, however, the witch is a woman.

The last known execution for witchcraft was recorded in 1782, at which time some 110,000 people had been tried and up to 60,000 had been executed – most of them women.[1] Not quite as well-known as the witch trials themselves, the Malleus maleficarum, or the Hammer of Witches, served not only as an extensive manual for the identification of witches but also advocated for their extermination.

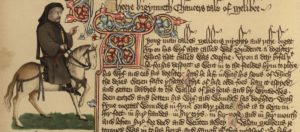

But even before the publication of the Malleus in 1487, there was De secretis mulierum, or On the Secrets of Women, an immensely popular treatise composed in the late-thirteenth or early-fourteenth century that still survives in more than 80 manuscripts. Drawing from medieval medical philosophy, the Secrets branded women as evil based on their biological composition and helped lay the foundation for the figure of the witch, which resulted in the deaths of so many women.

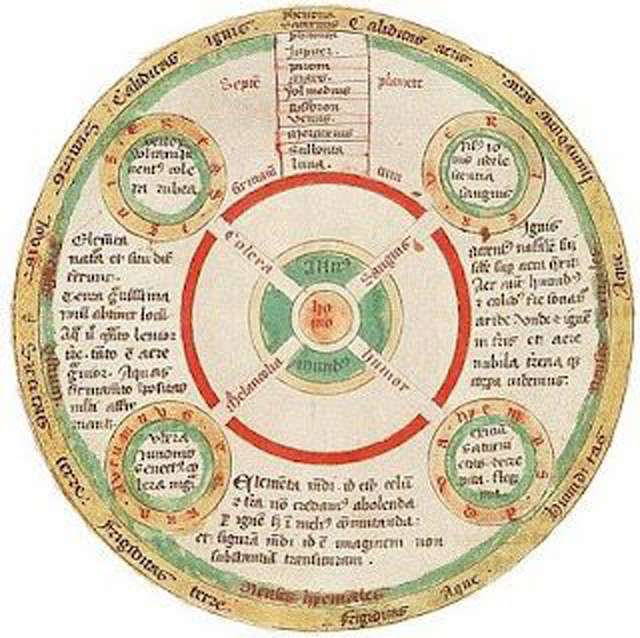

Specifically, the ideas about sexuality solidified through the intersections of medicine and religion situated women not merely as inferior to men but as polluted both physiologically and psychologically, via which they were eventually posited as predisposed to evil. The anatomical traits that distinguished women and men situated the sexes as binary opposites: they were a heterogenous, hierarchical pair. In conjunction with humoral theory, female softness and weakness were attributed to the body’s cool composition, while male strength and hardness were generated by their hot and dry climates.

Menstrual blood and semen, according to medieval physicians, were the defining essences of woman and man and were starkly contrasted in terms of their character. Menstrual blood was seen as an excess and, therefore, as physical evidence of the defectiveness of the female body because “it marked the inability of the body to become warm enough to refine blood.”[2] The blood itself was considered toxic because it was comprised of “unrefined impurities.”[3]

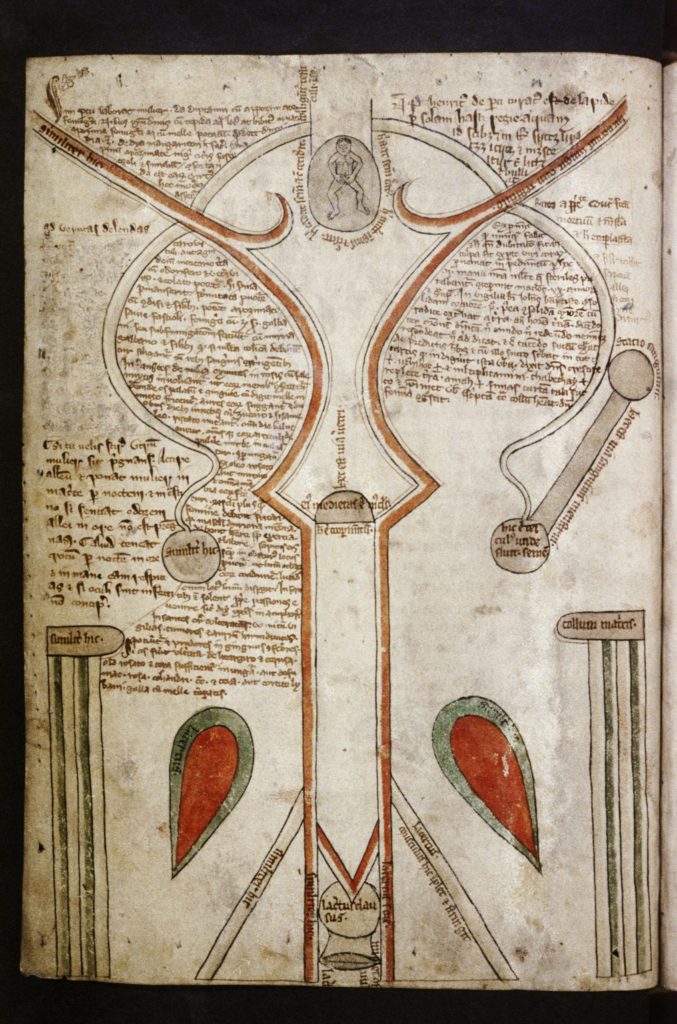

Although semen was thought to be a form of blood, it was blood that had been transformed into a precious substance within the testicles after traveling down the spinal cord from the brain.[4] Through its direct connection with the brain, male sexuality was associated with cognitive activity and rational, measured behavior. Women’s sexuality was posited as opposite: their bodies were considered passive, but women themselves were considered “profoundly sexual.”[5] The womb was central to the understanding of female anatomy and determined women’s passivity in contrast to men’s activity, as well as her association with the physical body. Moreover, women were characterized as open in relation to their genitalia, which subsequently indicated their openness to sexual activity and informed the idea that women were inherently lustful.[6]

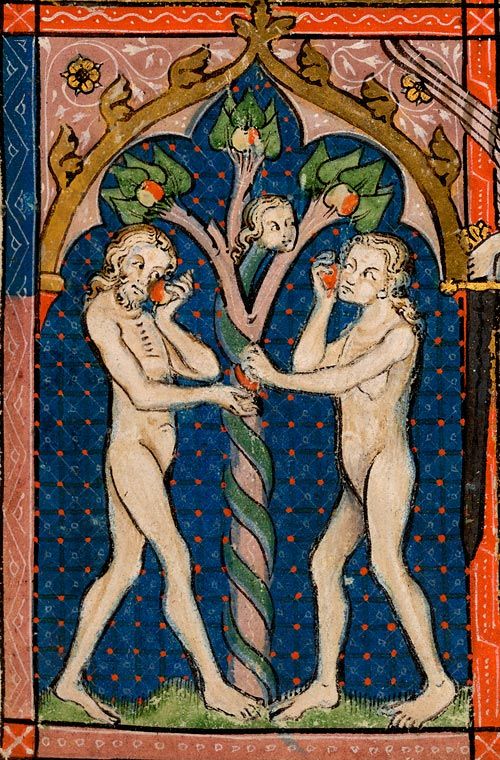

Attitudes toward women’s sexuality were also influenced by Christian beliefs, which associated sex with original sin. As the descendants of Eve, women were deeply connected with desire and consistently constructed as temptresses. In effect, they disproportionately bore responsibility where temptations of the flesh were concerned. Church fathers considered men “strong, rational, and spiritual by nature,” while women were “not only soft, but carnal,” in short, they “embodied sexuality” and continuously reproduced Eve’s initial temptation of Adam.[7]

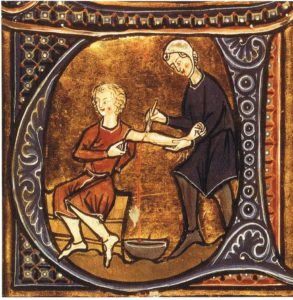

Drawing upon both biology and theology, medieval medicine synthesized the phallocentric understandings of women’s bodies and their perceived proclivity for sex and sin. While intercourse was believed to negatively alter men’s bodily composition, it was considered necessary for women, who were more likely to suffer from a lack of sexual activity. Menstrual blood was considered superfluous and conflated with pollution: its retention harmed the woman whose body failed to purge its humoral excess, and its expulsion threatened to poison others, causing illness and even death. Because their bodies were viewed as toxic, women were considered largely responsible for the transmission of diseases, especially those associated with sexual activity.

The Secrets then transmuted medical philosophy into overt misogyny and deemed women dangerous explicitly in relation to their sexuality. A particularly poignant passage describes the process by which women, essentially, drained and absorbed men’s life force through sex:

“The more women have sexual intercourse, the stronger they become, because they are made hot from the motion that the man makes during coitus. Further, male sperm is hot because it is of the same nature as air and when it is received by the woman it warms her entire body, so women are strengthened by this heat.”[8]

Describing menstruation as a time during which “many evils” arise, the Secrets cautions against intercourse, warning men that women are prone and prepared to deliberately cause them harm: “For when men have intercourse with these women it sometimes happens that they suffer a large wound and a serious infection of the penis because of iron that has been placed in the vagina.”[9] According to a commentary that often circulated with the manuscript, the man may not even notice that he has been wounded by the iron vindictively concealed within the vagina “because of the exceeding pleasure and sweetness of the vulva,”[10] an ominous addendum that vividly draws together desire, danger, and disease at the site of the female body.

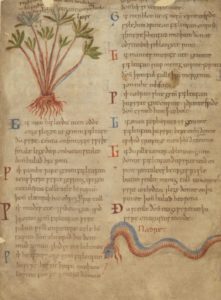

Even body parts not in direct contact with menstrual blood could become infected during menstruation. The Secrets describes the process by which a serpent is generated following the planting of hairs from a menstruating woman,[11] a proposition that viscerally evokes women’s connection with Eve and, more pointedly, with the devil.

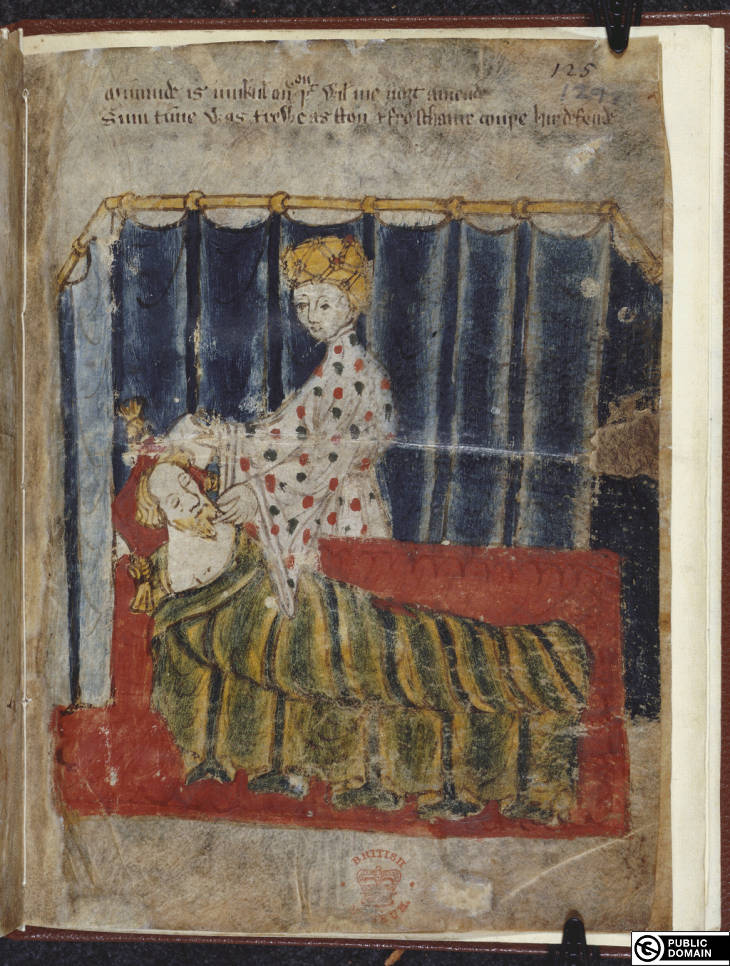

Older women were considered especially dangerous when their periods became intermittent, even more so following menopause when they failed to discharge superfluous fluid from their bodies and became increasingly noxious as a result. A passage from the Secrets explains as follows:

“If old women who still have their periods, and certain others who do not have them regularly, look at children lying in the cradle, they transmit to them venom through their glance … One may wonder why old women, who no longer have periods, infect children in this way. It is because the retention of the menses engenders many evil humours, and these women, being old, have almost no natural heat left to consume and control this matter, especially poor women, who live off nothing but coarse meat, which greatly contributes to this phenomenon. These women are more venomous than the others.”[12]

As the passage indicates, women who ceased to menstruate and subsisted on meager means were additionally threatening, a claim that further ostracized those already existing at outer margins of class society.

The innate malice of women’s bodies, illustrated so poignantly in the Secrets, was a disparaging ideological assemblage disseminated throughout the late Middle Ages, which became ingrained and interpreted in a way that unequivocally connected women’s sexuality with evil. The treatise emphasizes the wickedness of women’s physiological composition and psychological character and elevates their social stigma to its medieval pinnacle, perfectly epitomized in the text’s avowal that “woman has a greater desire for coitus than a man, for something foul is drawn to the good.”[13] And of course, men were not the only ones at risk; the innocent victims often included children.

It is these misogynistic ideas about women’s sexuality that seeded their demonization in the years that followed, as the Secrets served as a direct source for the Malleus maleficarum. Indeed, the most famous statement from the Malleus explicitly connects witchery with ideas about women’s sexuality rooted in the medieval period: “All witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which is in women insatiable.”[14]

Emily McLemore

Ph.D. Candidate, Department of English

University of Notre Dame

[1] Britannica.com, “Salem witch trials,” 25 Oct. 2020.

[2] Joyce Salisbury, “Gendered Sexuality,” Handbook of Medieval Sexuality, edited by Vern L. Bullough and James A. Brundage, New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc. (1996): 81-102, at 89.

[3] Salisbury, “Gendered Sexuality,” at 89.

[4] Danielle Jacquart and Claude Thomasset, Sexuality and Medicine in the Middle Ages, translated by Matthew Adamson, Cambridge: Polity Press (1988), at 13.

[5] Salisbury, “Gendered Sexuality,” at 84.

[6] Salisbury, “Gendered Sexuality,” at 87.

[7] Salisbury, “Gendered Sexuality,” at 86.

[8] Helen Rodnite Lemay, Women’s Secrets: A Translation of Pseudo-Albertus Magnus’ De Secretis Mulierum with Commentaries, Albany: State University of New York Press (1992), at 127.

[9] Lemay, Women’s Secrets, at 88.

[10] Lemay, Women’s Secrets, at 88.

[11] Lemay, Women’s Secrets, at 96.

[12] Les Admirables secrets de magie du Grand Albert et du petit Albert, MS Paris, Bibliothéque nationale, Latin 7148, fol. 2 r. 9 v., translated by Jacquart and Thomasset, Sexuality and Medicine in the Middle Ages, at 75.

[13] Lemay, Women’s Secrets, at 51.

[14] Heinrich Kramer and James Sprenger, Malleus maleficarum, translated by Montague Summers, New York: Dover (1971), at 47.