Most of us are familiar with the idea of Jesus as the Good Shepherd, but what about Jesus as a knight in shining armor, ready to do battle with a Black Knight called Satan or a fire-breathing dragon called Hell? In the literature of the Middle Ages, Christ was represented as such a knight, ready to save the day. Evidence of this can be found in Latin and Middle English sermons, religious lyrics, dramas, and hymns from the 13th to the 15th centuries. In one hymn, Christ’s crown of thorns actually transforms into a battle helmet!

Though the idea of the Christ Knight may seem strange, there is a biblical precedent. Ephesians 6:13-16 describes the armor of God’s soldier:

Wherefore take unto you the whole armor of God, that ye may be able to withstand in the evil day, and having done all, to stand. Stand therefore, having your loins girt about with truth, and having on the breastplate of righteousness; and your feet shod with the preparation of the gospel of peace; Above all, taking the shield of faith, wherewith ye shall be able to quench all the fiery darts of the wicked. And take the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God…

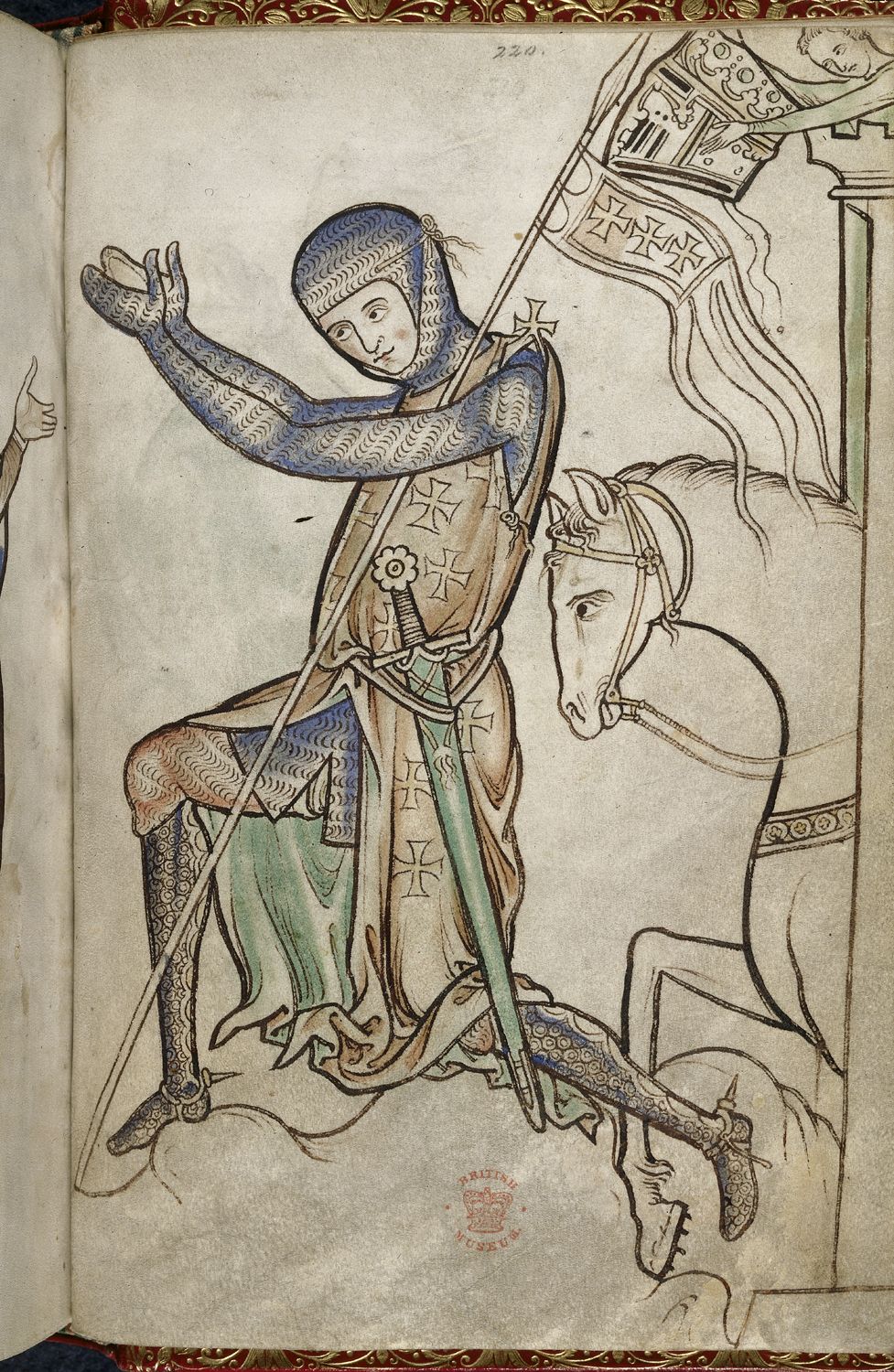

The Christ Knight could be represented in two different ways. He could be the courtly lover wooing his beloved lady and sacrificing his life for her in battle (a story about Christ’s love of the human soul), or he could be the fearless warrior who duels with the forces of evil, is crucified, and rises from the grave to free the souls imprisoned in Hell.

One of the earliest examples of the Christ Knight as courtly lover comes from an English manuscript of 1215. An anonymous author wrote the manuscript, Ancrene Riwle, whose purpose was to instruct three young ladies on religious and intellectual matters. In it, he tells a story about a lady in a castle of clay, surrounded by enemies. She is cold and unresponsive to the brave knight trying to woo her, yet he rides out to joust for her and dies on the battlefield, his body his shield, stretched out on the Cross.

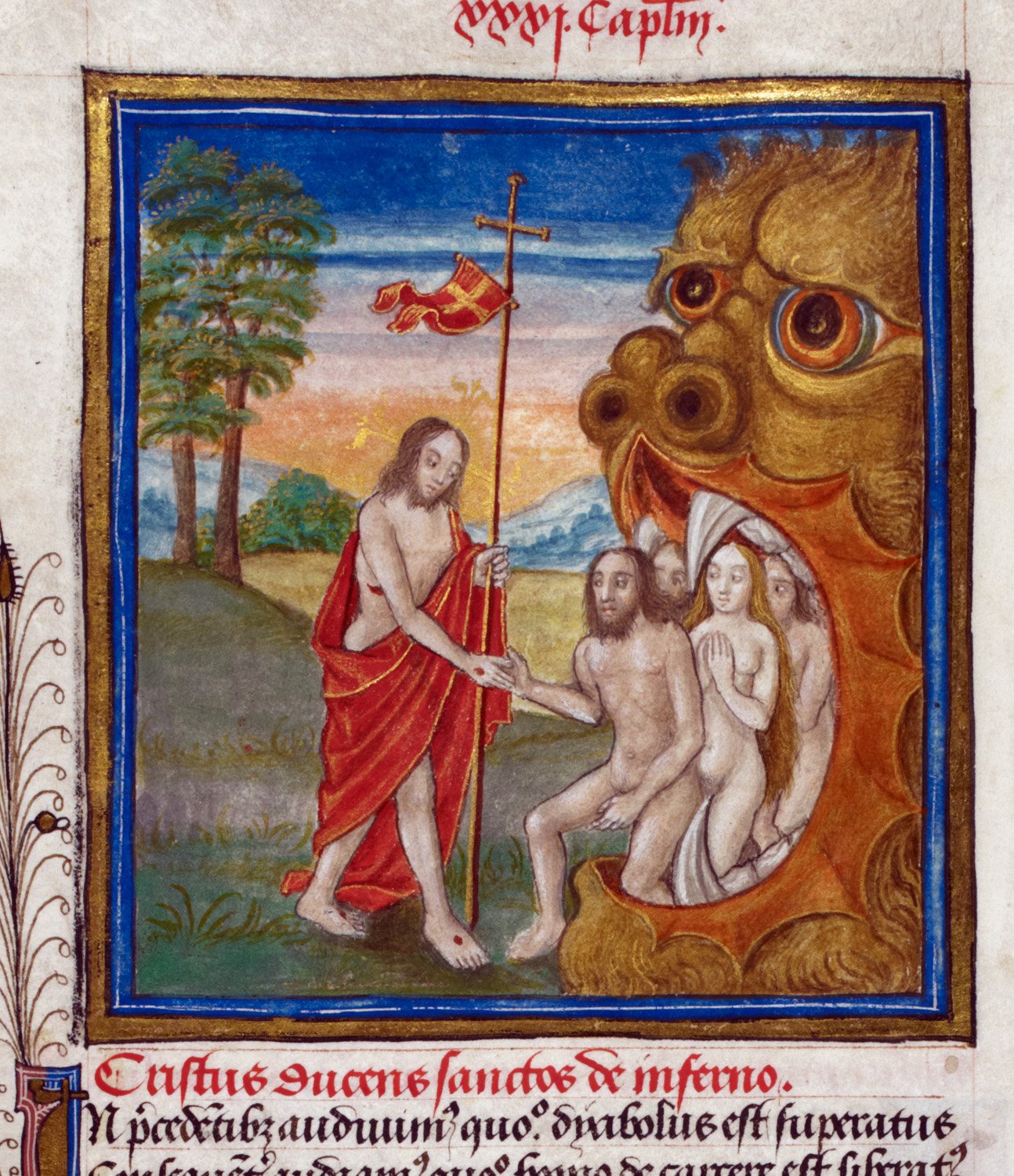

Christ as a warrior was also a popular motif. In a poem by William Herebert, written in 1333, Jesus is a young lord and valiant champion, not afraid of a good fight. In the Christian epic poem, Piers Plowman, Christ wears his “humana natura” as a helmet and armor to save all of mankind. Though he’s crucified on earth, he rises after death to storm the gates of Hell, described as a castle. The devils in Hell are unprepared for the attack, because Christ had come “disguised” as a simple human being rather than a great king. This disguise is payback to Satan for wearing the disguise of a snake to tempt Adam and Eve. “Jousting” with Satan in the “armor” of human flesh, Christ frees the souls of the good people (such as Moses and Adam) who lived on earth before his birth. Clearly, the Christ Knight was a powerful Medieval symbol.

James Cotton

PhD Candidate

Literature Program

University of Notre Dame