[This post, part of an effort to merge our undergraduate and graduate blogs, was written in response to an essay prompt for Kathryn Kerby-Fulton's undergraduate course on "Chaucer's Biggest Rivals: The Alliterative Poets." It comes from the former "Medieval Undergraduate Research" website.]

Original text of Fitt III, lines 1150-1177

At þe fyrst quethe of þe quest quaked þe wylde.

Der drof in þe dame doted for drede,

Hiȝed to þe hyȝe bot heterly þay were

Restayed with þe stablye, þat stoutly ascryed.

Þay let þe herttez haf þe gate, with þe hyȝe hedes,

Þe breme bucket also, with or brode paumez;

For þe free lorde hade defende in fermysoun tyme

Þat þer schulde no mon meue to þe male dere.

Þe hindez were halden in with ‘Hay!’ and ‘War!’

Þe does dryuen with gret dyn to þe depe sladez.

Þer myȝt mon se, as þay slypte, slentyng of arwes;

At vche wende vnder wande wapped a flone,

Þat bigly vote one þe broun with ful brode hedez.

What! þay brayen and bleden, bi bonkkez þay deȝen,

And ay rachches in a res radly hem folȝes,

Hunterez wyth hyȝe horne hasted hem folȝes,

Wyth such a crakkande kry as klyffes haden brusten.

What wylde so atwaped wyȝes þat schotten

Watz al toraced and rent at þe resayt,

Bi þay were tened at þe hyȝe and taysed to þe wattrez,

Þe ledez were so learned at þe loȝe trysters;

And þe grehoundez so grete þat geten hem bylyue

And hem tofylched as fast as frekez myȝt loke

Þer ryȝt.

Þe lorde, for blys abloy,

Ful oft con launce and lyȝt,

And drof þat day with joy

Thus to þe dark nyȝt.

Translation

At the first word of the quest quaked the wild animals.

Deer drove into the dale, demented by dread,

They hastened to the high ground, but cruelly they were

Turned back by the ring of beaters, that mightily cried out.

They let the harts pass, with their high heads,

And the fierce bucks also, with their broad flat antlers;

For the noble lord had forbidden in the time of the close-season

That any man should rouse the male deer.

The hinds were hailed in with “hey!” and “ware!”

They drive the does with great din to the deep valleys.

There one may see, as they were loosed, the slanting flight of arrows;

At each wind under the boughs swished an arrow,

That powerfully bit into the brown flesh with very broad heads.

What! They bray and bleed, by banks they die,

And all the while hounds in a rush promptly follow them,

Hunters with loud horns hastened after them

With such a cracking cry as if cliffs had burst.

Whatever wild creature eluded the men that shot

Was all pulled down and torn open at the receiving stations,

By the time they were harnessed at the high ground and driven to the waters,

The men were so skilled at the low hunting stations;

And the greyhounds so great that they seized them quickly

And pulled them down as fast as men could look

Right there.

The lord, transported by bliss,

Very often did shoot and dismount,

And passed that day with joy

In this way till the dark night.

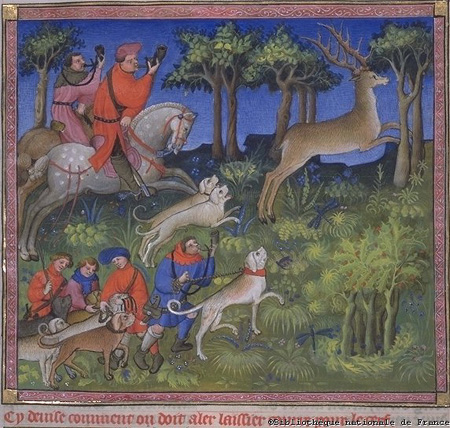

This passage from the beginning of the first hunt scene sets the stage for the following seduction attempt scenes in which the enthusiastic and energetic pursuit of the hunt is sublimated in the mirrored pursuit of the bedroom. Alliteration works to convey the urgency and vigor of the action, as in line 1151: “Der drof in þe dale, doted for drede,” where the repetition of the “d” sound mimics the thudding of hooves. The frequency of the alliteration in this line drives home the desperation of the animals’ flight. In another example, alliteration of the “s” sound in line 1160 aurally portrays the whistling of arrows as they “slypte” and go “slentyng” through the air. The scene is then fraught with imagery that is highly charged, masculine, and sensual. Vaguely erotic images describe the chaos and destructive action of the hunt, such as in lines 1161-62, where it is said that “a flone… bigly bote on þe broun” (“an arrow… powerfully pierced the brown flesh”). This is perhaps best exemplified in the bob and wheel, in which “þe lorde, for blys abloy, / ful oft con launce and lyȝt, / And drof þat day wyth joy / Thus to þe derk nyȝt.” The description of the lord’s pleasure in the hunt, apparently so great that he spends the entirety of the day from early morning until dark of night in the pursuit, is evocative of (repetitive) sexual climax.

While he pursues this pleasure outdoors with wild game as the prey, his wife pursues it indoors as she attempts to ensnare Gawain. In the hunt, the male hunters pursue female deer (hinds and does) exclusively as the male deer (harts and bucks) are illegal to shoot. In contrast, the seduction scene reverses the gendered roles of hunter and hunted as the woman pursues the man. The hunt scene is overwhelmingly masculine and virile as it describes men energetically making use of their weapons to lay low their conquests. It is an emphatically loud scene, filled with the clamor of the hunt, the dashing of hooves, braying of hounds, and the cracking cries of the hunters. This is all reversed in the following scene, where the lady makes use of her feminine weapons. In contrast to the hunt, the bedroom seems extraordinarily quiet, as Gawain’s silent room is quietly invaded by the lady, and they humorously exchange light flirtation. Yet the rushing of the hunt scene hangs over that of the bedroom, and tinges it all the more with a sense of restrained lust.

Marie Borroff’s translation is generally successful in the description of the scene, maintenance of the alliteration, and representation of the imagery. While at times it changes for the sake of maintaining meaning in recognizable words, the alliteration for the most part matches the original consonants, successfully maintaining the sonic qualities and their aural imagery. There are, however, some questionable moments, in which the translation fails to be effectively descriptive for modern English. At line 1158, for example, Borroff translates the line as “The hinds were headed up, with “Hey!” and “Ware!” The line is easily translated into modern English, as most of the words remain the same. However, Borroff chooses to translate “halden in” (the literal meaning of which is “hailed in”) as “headed up.” The reasoning for this is unclear – the modern English translation perfectly maintains the meaning and alliteration, and the phrase “hailed in” is easier to understand than “headed up.” While fortunately the import of the line is not altered, Borroff’s translation makes the text slightly less clear and accessible than it is even in its original form.

This same issue of archaic, difficult to access diction occurs just a line above in the case of Borroff’s use of the word “demesne” which Borroff defines in the margin as “kingdom.” Perhaps she deems this important for maintaining the alliteration of the line between words beginning with “d.” Even in this case, however, we might imagine other possible choices, for example, “district,” that might maintain the alliteration of the line and perhaps even better describe the geo-political reality. But the fact remains that in the original line, the “d” is not alliterated – “dere” is the lone “d” word, and the alliterated consonant is instead the “m” of “mon,” “meue,” and “male.” Borroff maintains this alliteration in her translation of these words as “man,” “molest,” and “male,” respectively (although two of these translations are obvious). Furthermore, the original line makes no mention of a kingdom at all. Borroff’s addition of this detail seems more intended for the sake of informing modern readers of the political or legal aspects of land ownership and hunting laws than for the sake of literally representing the lines.

For the most part, though, these changes are slight and the translations are still quite faithful. The largest difference, however, is in Borroff’s translation of the bob and wheel. The general meaning of the lines still comes across, but the powerfully suggestive imagery of the original bob and wheel is significantly diminished. Borroff does try to maintain this sense, with phrases like “sheer delight” and “pleasures rare,” yet unfortunately the originally striking imagery falls apart under the demands of making a translation in modern English that maintains equal syllabic length and comparable rhyme scheme. Overall, though, the translation is impressive, considering the demands on the translator to keep the modern version as close to the original meaning while at the same time replicating original poetic devices. The Middle English is clearly preferable in its ability to convey the ferocity, virility, and sensuality of the hunt all at once, but for readers of modern English, Borroff’s translation is impressive, all things considered.

Angela Bird

University of Notre Dame