In continuing our previous conversation surrounding the semantics of trǫll in Old Norse-Icelandic literature, and the evolution of the term in modern English, we turn our attention to contemporary applications of the term, particularly in the context of internet trolls and trolling. The concept of internet trolls builds on the image of a goblin or a giant stalking and skulking about in the dark and the implication that these people are perhaps ugly. This produces a harmful stereotype of “somebody sitting on their bed that weighs 400 pounds,” as Donald Trump remarked in a 2016 debate, in a diversionary (and rather ironic) attempt to draw attention away from evidence of Russian meddling in his favor during the most recent U.S. presidential election.

However, the reality is that the online shield of anonymity operates as a cloak of invisibility, not unlike the invisibility cloak worn by Harry Potter as he explores Hogwarts castle at night or the tarnkappe “cloak of concealment” that Sîfrit [Siegfried] receives from a dwarf named Alberich in the Middle High German Nibelungenlied. Online anonymity often renders one’s physical fitness either irrelevant or artificial anyway, while at the same time it protects the identities of nefarious actors, thereby allowing them to troll the internet unseen or in disguise. Indeed, the ugliness of internet trolls has everything to do with their emotionally pathetic behavior characterized by cowardly hatred and blind rage.

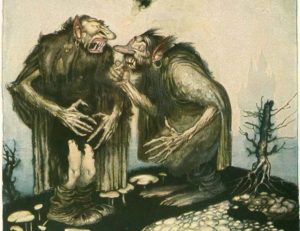

Considering this semantic range, a trǫll is not much more specific than the general concept of a “monster” that encompasses everything from sorcerers to goblins and giants to dragons. As we have seen, the medieval tradition bears out the vagueness of this term as a category of being. While the giant-trǫll may be one of the most common applications of the term in saga literature, modern representations of trolls suggest far more uniformity than evidence from medieval literature demonstrates.

However, even the modern sense of troll retains some flexibility, for in addition to the giant-trǫll, much smaller goblin-like representations of trolls (manifesting in the modern troll doll phenomenon) also features prominently in modern medievalism from early modern fairy tales, like those in the Grimm brothers‘ and Hans Christian Andersen‘s collections, to contemporary fantasy literature and film.

If a troll is principally a monster lurking in the shadows, then the contemporary use of the term to describe a form of cyber-bullying is especially apt. Not everyone agrees on the precise definition of a modern internet troll, and it seems that—in this sense—the semantic ambiguity of the word endures. For some a troll is specifically someone interested in online agitation for the purposes of entertainment, for others a troll is essentially comparable to a cyber-bully and internet stalker. As with some of their medieval counterparts, internet trolls may hunt in packs or prowl alone, though they no longer hide under bridges and caves but instead lurk in the recesses of the world wide web.

The monstrous vitriol, stalking and harassment in which internet trolls engage is notorious, especially on social media platforms such as Twitter, and has furthered cultural trends in discourse toward antagonism rather than cooperation, leading Melania Trump to launch a campaign as first lady against cyber-bullying and online harassment, in other words against the internet trolls.

Internet trolls have developed a terrible reputation as being a cowardly group of angry individuals. Bernie Sanders, despite unequivocally disavowing any internet trolls among the ranks of his supporters and calling for a government of compassion and justice, suffered from a lasting stereotype of the “Bernie-bro” during both his presidential campaigns, which characterized his grassroots movement as an army of internet trolls, primarily comprised of angry white men terrorizing Twitter. Although a recent Harvard study revealed that the “Bernie-bro” narrative was a myth and suggested that political trolling occurred by supporters of every Democratic candidate at similar rates, this caricature proved impossible for Sanders to shake as a result of the public disdain for internet trolls.

This Harvard study, however, highlighted a different but related issue—namely how ubiquitous trolling has become and the damage it has wrought upon ethical discussion and political conversations in this country regardless of which candidate one supports or with which party one affiliates.

Although Joe Biden does not have the same online presence as Sanders, and has promised to restore decency, he nevertheless embodied the trollish spirit of combativeness, which permeates social media discourse, in his everyday interactions with voters on the campaign trail. Biden repeatedly told those who disagree with him that they should vote for someone else, and at times getting into near physical altercations with Americans who challenged him on his record and policies. Despite both Democratic candidates’ feisty reputations (or in Sanders’ case the reputation of his supporters), both Bernie and Biden were notably amicable and referred to each other frequently and intentionally as friends during the primary. Sanders‘ recent endorsement of Joe Biden for president as the Democratic nominee then comes as no surprise and underscores a shared sense of party unity with the goal of winning back the White House.

When responding to charges of a “Bernie-bro” culture among his supporters, Sanders has wondered if again, as in 2016, Russian media (especially bots and trolls) might be targeting his campaign, though this claim has been contested. Sanders also noted that in fact some of the most vicious trolling has been aimed at his surrogates and supporters of his campaign and progressive agenda, especially women of color, including his campaign co-chair Nina Turner, and the freshmen congresswomen known as “the squad” three of whom have endorsed Sanders, namely Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, and Rashida Tlaib. In making this point, Sanders shifted the spotlight onto some of the most marginalized voices in our government who face some of the most vile and threatening trolls haunting the internet.

In our own field of medieval studies, we have observed a similar phenomenon. Medievalists of color, including junior scholars such as Dorothy Kim, Mary Rambaran-Olm, Adam Miyashiro, Sierra Lomuto, Seeta Chaganti and others, have become the target of alt-right trolls as a result of their speaking up against white nationalist appropriations of medieval history, literature and culture and raising the issue of racism within the field itself (and not without resistance). Professional internet trolls, like Milo Yiannopoulos, have pursued ad hominem attacks on some of these scholars in the guise of pseudo-academic arguments, and the internet troll forces involved with the alt-right movement have taken up his call to arms against our colleagues of color in the name of white supremacy, masquerading as nationalism (but centered on issues of ethnocentrism and notions of cultural homogeneity). The threat from modern trolls is indeed as serious as encountering a monstrous trǫll in an Old Norse-Icelandic saga.

Many have argued that Donald Trump is a cyber-bullying wizard, and his supporters notoriously seem to follow his lead. This characterization marks the president as essentially the mesta trǫll “greatest troll” capable of dragon-scale destruction via the internet, which renders his wife’s campaign against online harassment profoundly paradoxical. Moreover, whether it’s demonizing undocumented immigrants, insulting the squad, or attempting to rebrand covid-19 as the “Chinese virus” rather than simply calling it the novel coronavirus, the president is infamous for his straightforwardly offensive, racially loaded and politically incorrect tweets, which inflame racial tensions and partisanship. Trump’s relentless trolling of Climate Change activist Greta Thunberg is perhaps his most opprobrious internet feud, surpassing even his decade-long spat with Rosie O’Donnell.

While it only takes one brief glance at Trump’s Twitter account to recognize his ferocity, dedication and skill in trolling his political opponents, it is important to recognize that he also receives his fair share of troll-attacks. Perhaps as a result of observing Trump’s effective trolling, Democrats and those criticizing the president have resorted to similar tactics, and have been praised for it, especially when Trump’s statements are trafficking in bigotry or misinformation. Indeed, if the Democratic nominee means to best Trump in the general election, and thereby defeat the greatest troll, as it were, it will certainly require strength of character and no small amount of courage.

Perhaps the most infamous subcategory of internet troll, which has come under intense scrutiny as a result of their involvement in the 2016 presidential election in the United States, is the Russian troll. The involvement of Russian trolls (and bots) has received a share of credit for Donald Trump’s surprising victory over Hilary Clinton, and the president’s critics have alleged collusion between the Trump campaign and the Russian government, which resulted in a special investigation by Robert Mueller centered on whether there was a conspiracy (with Russia) or obstruction of justice on the part of the administration. This produced the famous Mueller Report that indicted 13 Russian nationals linked to tampering with the U.S. election. This Russian strategic operation was organized by the Internet Research Agency, which CNN describes as “a Kremlin-linked Russian troll group, [which] set up a vast network of fake American activist groups and used the stolen identities of real Americans in an attempt to wreak havoc on the U.S. political system.”

Now in 2020, the U.S. again finds itself in yet another battle against Russian trolls and the spread of misinformation and disinformation. Russian trolls seem to be focused on antagonizing and disaffecting groups and individuals thereby turning Americans on Americans, as the Mueller Report outlines a “strategic goal to sow discord in the US political system.” Although Russian virtual propaganda and social media trolling certainly may have fanned the flames, the sad truth is the the fire was already burning. What’s worse, anyone and everyone arguing online becomes a potential Russian troll, providing scapegoats and discrediting of the hard work and dedication of many Americans calling for social, racial, environmental and economic justice, and necessary reform to meet these needs.

As the loudest and most provocative views often receive the most traction and attention, especially on social media, internet trolls—whether an operative from the Internet Research Agency or simply troubled person lashing out online—cast long shadows, effectively silencing all those softer voices and further destabilizing civil discourse.

In both medieval literature and modern times, we must fight the trolls and the horrors they bestow upon human society. While I am suggesting a sort of call to action against internet trolls and trolling, it is expressly not a call for tone-policing. Critique, even the sharpest criticism—especially of public officials and elected representatives—must be uncensored so the people may speak freely and in whatever (and whichever) language they choose, whether vulgar or polite in tone. However, I am suggesting that we consider changing our rhetorical strategy as a nation and a world.

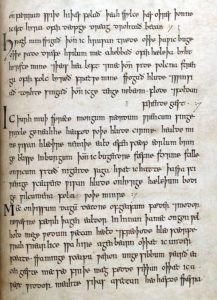

Legendary heroes often fight trolls by matching their strength and ferocity, by fighting fire with fire, but I believe a different path might be more efficient. Perhaps it is cliché for a medievalist to suggest a hagiographical approach, but I would contend that we could learn a lesson from St. Juliana’s contest with a demon (267-558) in the Old English Juliana by Cynewulf recorded in the Exeter Book (Exeter Cathedral Library MS3051). As a medieval saint might when facing a devil, I believe that it is often best (and more rhetorically effective) to match vice with virtue, anger with empathy, belligerence with amicability and hate with love in order to transform political conversations in America toward more ethical practices.

This rhetorical strategy, meeting vice with virtue, is the centerpiece of the late classical Christian epic, Prudentius’s Psychomachia, often regarded as the first medieval allegory which establishes the robust tradition which follows. In the Psychomachia, demonic vices fight against saintly virtues in what amounts to a battle for the soul of humanity, a phrase which is repeatedly invoked regarding our current political moment. Although the Psychomachia frames its narrative in reductive notions of good and evil, it nevertheless argues that the strongest way to combat monstrous vices ira “wrath,” superbia “pride,” luxuria “luxury” and avaritia “greed” is with inverse behavior, in other words, the heroic virtues of patientia “patience,” humilitas “humility,” sobrietas “sobriety,” and operatio “service.”

Of course, we must continue the constant battle against what can seem like an endless horde of internet trolls, and it is all too tempting, and necessary at times, to get into the proverbial mud and valiantly take the fight to them in their digital lairs (usually located somewhere in the comment section) as heroes often do in saga literature and fantasy novels.

We might also note that in the Hobbit, the grey wizard Gandalf initiates and perpetuates an argument between three stone-trolls in an effort to stall and prevent the monsters from devouring Thorin’s company (ch 2: “Roast Mutton“). Gandalf’s ventriloquism mirrors the trolls‘ level of discourse, and eventually not only does their bickering delay their eating the dwarves, it causes the trolls to forget about the approaching dawn, which turns them to stone. Perhaps there is something of a serendipitous metaphor in the argument between the wizard and the trolls in the Hobbit, which suggests that in order to overcome trolls, one must beat them at their own game and hope they self-destruct.

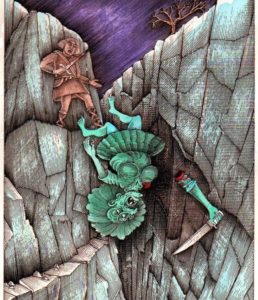

Indeed, like Grettir wreaking vengeance upon the trǫllkona mikil “great troll-woman” in Grettis saga (ch. 65), it may be that sometimes the only way to respond to a troll is to retaliate in some form. But there is also another kind of strength, kinder but no less powerful. While it is often impossible to starve trolls by ignoring them, and acknowledging that no single strategy will always prove effective, it may nevertheless be that the most productive way to defeat internet trolls is through sustained civil discourse in the spirit of generosity. In other words, kill them with kindness.

Richard Fahey

PhD in English (2020)

University of Notre Dame

Texts and Translations

Andersen, Hans Christian. Fairy Tales and Stories, translation by H. P. Paull (1872).

Byock, Jesse. Grettir’s Saga. Oxford University Press (2009).

Grimm, Jakob, and Wilhelm Grimm. Grimm’s Household Tales, translation by Margaret Hunt (1884).

Cynewulf. Juliana. In Anglo-Saxon Narrative Poetry Project, translation by Aaron K. Hostetter. Rutgers University (2007).

Margaret Armour. The Nibelungenlied. In Parentheses Publications (1999).

Mueller, Robert. Report On The Investigation Into Russian Interference In The 2016 Presidential Election. Special Counsel Office (2019).

Prudentius. Psychomachia. In Prudentius, with an English translation by H.J. Thomson (1949).

Rowling, J. K. Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. Bloomsbury (1997).

Tolkien, J. R. R. The Hobbit, or There and Back Again. Allen & Unwin (1937).

Further Reading

Ashkenas, Jeremy. “Was It a 400-Pound, 14-Year-Old Hacker, or Russia? Here’s Some of the Evidence.” The New York Times (2017).

Chaganti, Seeta. “Statement Regarding ICMS Kalamazoo.” Medievalists of Color (2018).

Fahey, Richard. “Medieval Trolls: Monsters from Scandinavian Myth and Legend.” Medieval Studies Research Blog. University of Notre Dame (2020).

Grendell, Alexis. “Should We Have a Right to Troll Politicians on Twitter?” The Nation (2019).

Hanson, James. “Trolls and Their Impact on Social Media.” University of Nebraska-Lincoln (2018).

Jones, Brandon G. “Harvard Scientist Analyzes 6.8 Million Tweets, Finds Bernie Sanders Supporters Are NOT More Abusive.” ABC 14 News (2020).

Kim, Dorothy. “White Supremacists Have Weaponized an Imaginary Viking Past. It’s Time to Reclaim the Real History.” Time (2019).

—. “Teaching Medieval Studies in a Time of White Supremacy.” In the Middle (2017).

Klempka, Allison and Arielle Stimson. Anonymous Communication on the Internet and Trolling. Concordia University (2017).

Kosoff, Maya. “Why the Right’s Dark-Web Trolls Are Taking Over Youtube.” Vanity Fair (2018).

Lahut, Jake. “Joe Biden Gets Away with Yelling at Voters, and May Even Benefit from It.” Business Insider (2020).

Leigh, Kira. “Fantastic Internet Trolls and How to Fight Them.” Medium (2017).

Lewis, Simon. “Bernie Sanders to Online Trolls: Stop ‘Ugly Personal Attacks.” Reuters (2020).

Lindgren, Émelie Vangen. “Trolls in Your Comment Section and How to Fight Them.” Medium (2017).

Lomuto, Sierra. “White Nationalism and the Ethics of Medieval Studies.” In the Middle (2016).

Martin, Tess. “Racism 101: Tone Policing.” Medium (2018).

McQuade, Barbara and Joyce White Vance. “These 11 Mueller Report Myth Just Won’t Die. Here’s Why They’re Wrong.” Time (2019).

Miyashiro, Adam. “Decolonizing Anglo-Saxon Studies: A Response to ISAS in Honolulu.” In the Middle (2017).

Noor, Poopy. “Trump’s Troll-in-Chief? Once Again, Nancy Pelosi Bites Back.” The Guardian (2019).

Perry, David. “How to Fight 8Chan Medievalism—and Why We Must.” Pacific Standard (2019).

Mary. “Misnaming the Medieval: Rejecting ‘Anglo-Saxon’ Studies.” History Workshop (2019).

Ray, Alison. “The Psychomachia: An Early Medieval Comic Book.” British Library (2015).

Read, Bridget. “I’m Sorry, What Did Biden Say to This Voter?” The Cut (2019).

Roll, Nick, “A Schism in Medieval Studies, for All to See.” Inside Higher Ed (2017).

Sarsour, Linda. “Yes, Women of Color Support Bernie Sanders. It’s Time to Stop Erasing Our Voices.” Teen Vogue (2019).

Silver, Nate. “Donald Trump is the World’s Greatest Troll.” FiveThirtyEight (2015).

Spencer, Kieth A. “There Is Hard Data That Shows ‘Bernie Bros’ Are a Myth.” Salon (2020).

Sax, David. “‘If You Fight Fire with Fire, Everyone Burns’: How to Catch a Troll Like Trump.” The Guardian (2016).

Sebenius, Alyza. “Russian Trolls Shift Strategy to Disrupt U. S. Election in 2020.” Bloomberg (2020).

Stratton, Erica. “6 Ways to Fight Trolls Instead of Starving Them.” The Airship (2014).

Vinsonhaler, Christine. “The HearmscaÞa and the Handshake: Desire and Disruption in the Grendel Episode.” Comitatus 47 (2016): 1-36.

Waters, Lowenna. “AOC Destroys ‘Misogynist’ Twitter Troll with One Simple Comment: ‘I Don’t Give a Damn.” Indy100 & Independent (2019).