The advent of e-books has prompted discussion about the experience of reading and its relationship to a material text. Opponents of digital books speak fondly of holding a book in hand, the ability to feel the weight of the object and physically see yourself progress through the text. There is a sense of something lost when this object changes form, when paper becomes plastic, when clicking replaces page-turning, when your sense of place in the text is measured by percentage rather than pages.

Of course, changes in the way in which we materially experience reading have been going on far longer than the recent shift to digital media. The book versions of older texts are in many ways even more distant from their original form than digital books are to their print ancestors.

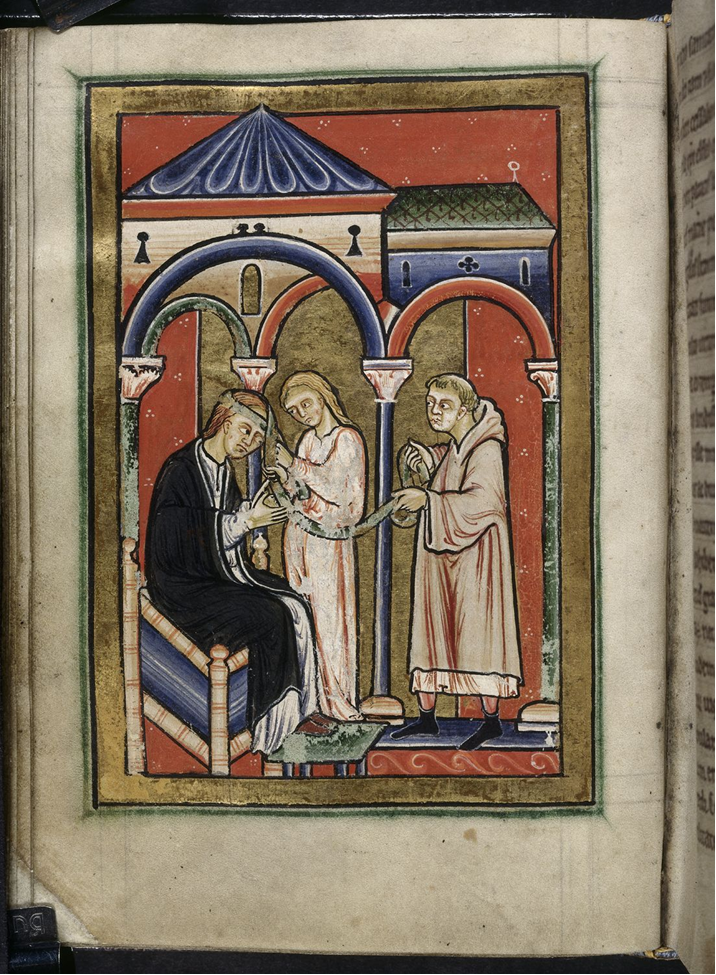

While some these changes are obvious to the readers—the illuminations, the particular handwriting, the spacing of the text on the page—editors of print editions also make choices that are less apparent. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight provides an interesting example of how much print can transform a medieval manuscript, as seen in the editors alterations of the bob and wheel form. In this form, the stanza ends with two short lines (the bob) followed by four rhyming lines (the wheel):

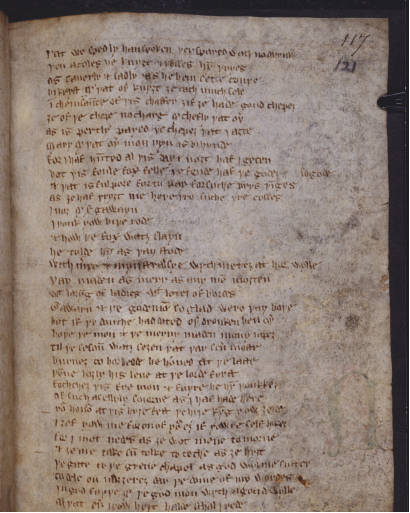

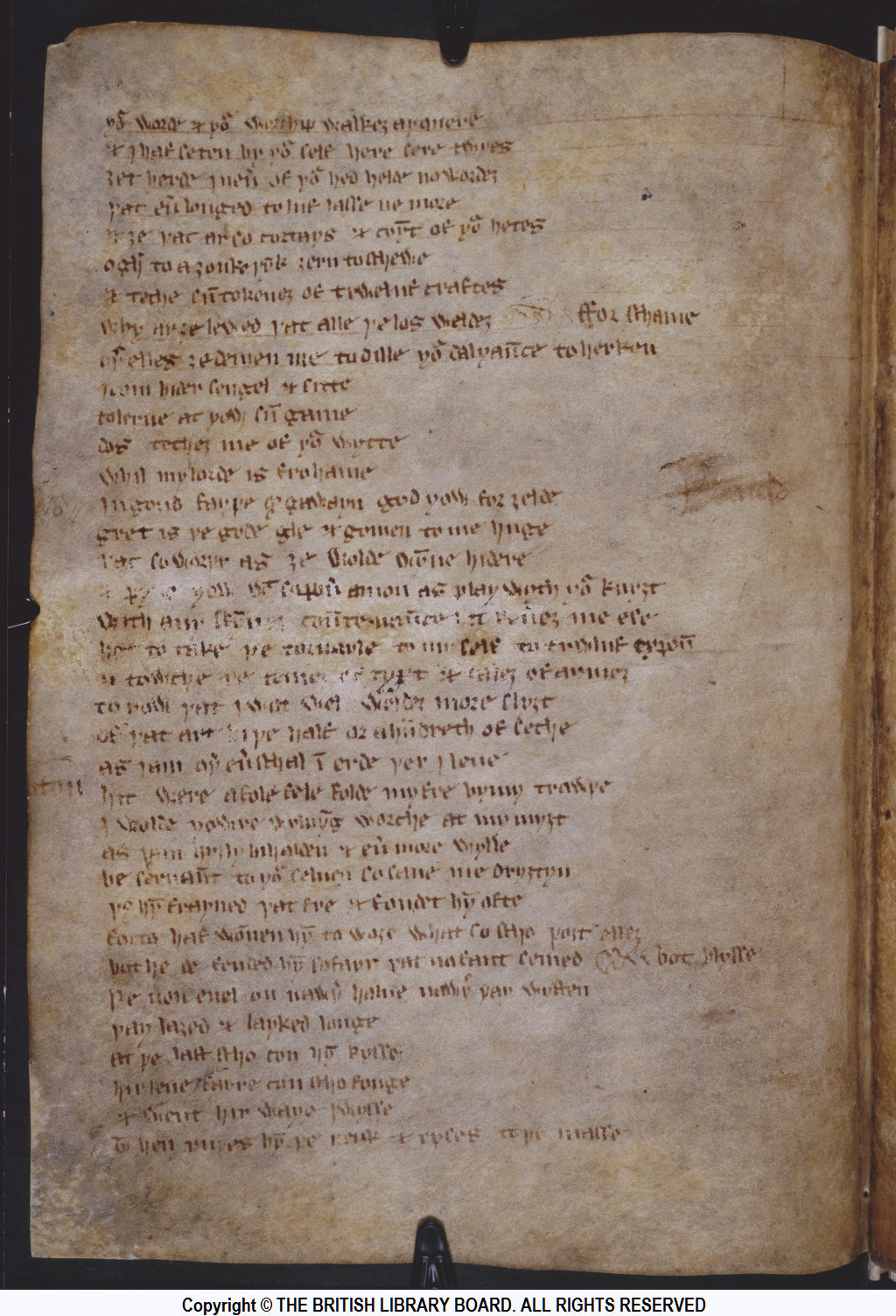

The editors follow this form exactly, but as Kathryn Kerby-Fulton notes in Opening Up Middle English Manuscripts, the placement of the bob is not as regular in Gawain as modern editions would lead us to believe. Instead, the bob is written in the margin, often not directly before the wheel. Compare the following:

Modern Edition (eds. Andrew and Waldron)

Bot he defended hym so fayr þat no faut semed,

Ne non euel on nawþer þay wysten

Bot blysse.

Þay laʒed and layked longe;

At þe last scho con hym kysse,

Hir leue fayre con scho fonge,

And went hir waye, iwysse. (1551-1557)

Manuscript

As Kerby-Fulton argues, this fluid placement of the bob changes our understanding of certain passages, since it can often be attached to several lines and still be grammatically correct. Andrew and Waldron translate the modern version of lines 1552-3 as “nor were they aware of anything but pleasure.” In the original text, however, the placement of the bob would render the line “But he defended him so fair that no fault seemed but pleasure.”

The placement of the bob obviously has some impact upon our understanding of the poem. But what about that illusive “reading experience”? The modern editions fundamentally change this as well. Imagine, for a minute, that you are a medieval reader. When you read the bob, do you hear it exactly where it is placed? Do you hear it where the modern editor would move it to? Or do you hear it after multiple lines? Perhaps your eye floats out to it on several occasions, placing it in multiple positions and playing with its flexible meanings. Gawain, after all, is a poem of playful language and deceit, and the poet is noted for his use of puns in Pearl.

No modern edition has been printed that maintains the manuscript’s irregular placement of the bob. The solution, then, is to turn back to the manuscript: to printed facsimiles, but also, perhaps counterintuitively, to digital scans of the original pages.

Jane Wageman

MA Candidate

Department of English

University of Notre Dame

Works Cited

Andrew, Malcolm, and Ronald Waldron. The Poems of the Pearl Manuscript: Pearl, Cleanness, Patience, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. University of California Press, 1982.

Kerby-Fulton, Kathryn, Maidie Hilmo, and Linda Olson. Opening Up Middle English Manuscripts: Literary and Visual Approaches. Cornell University Press, 2007.