by Jean McManus, Catholic Studies Librarian

We recently acquired a manuscript German Catholic prayer book, made in Pennsylvania in 1799. Following is a short description of what we know about this particular manuscript book, and a comparison with a printed German Catholic prayer book that was published in Baltimore around the same time (1795).

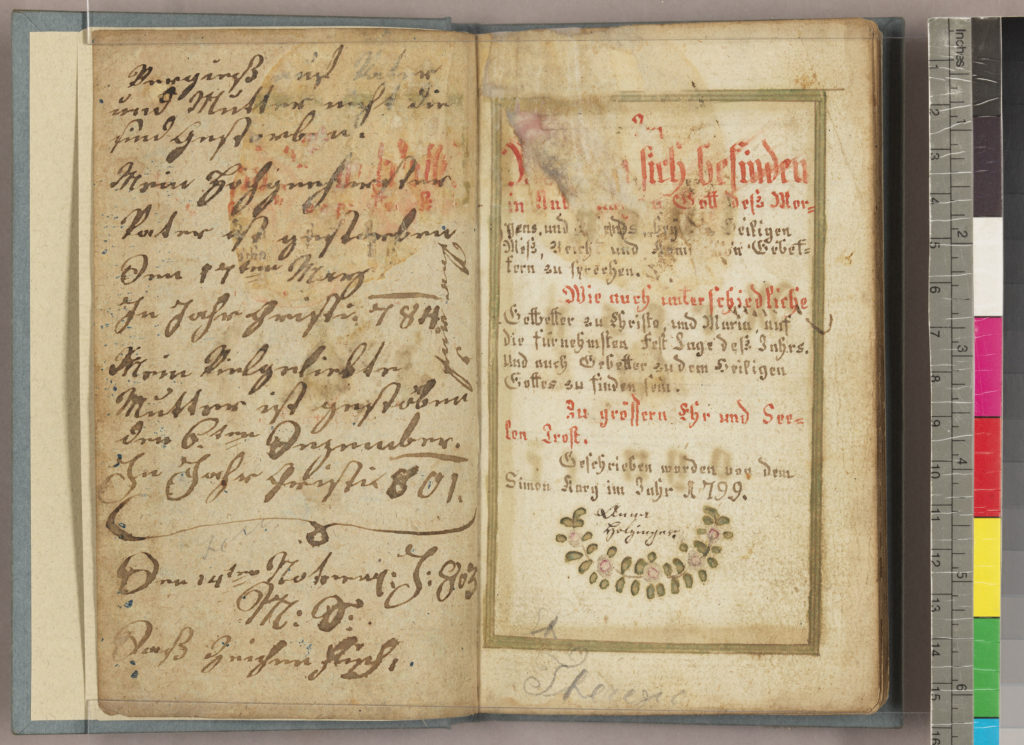

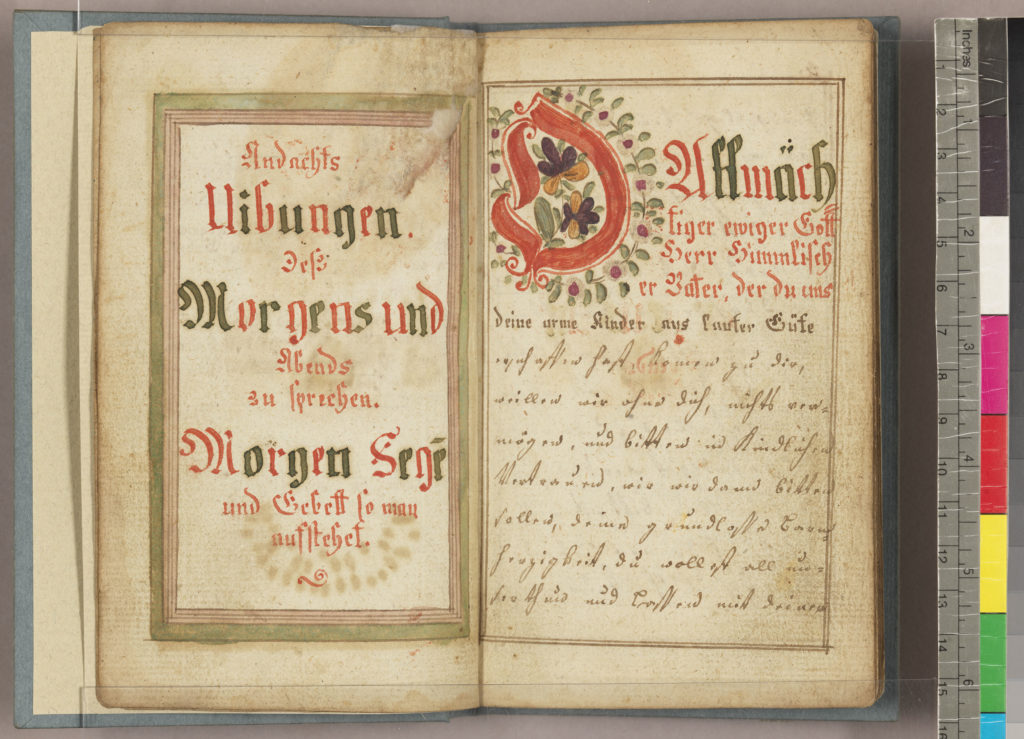

This beautiful manuscript’s opening page describes its contents:

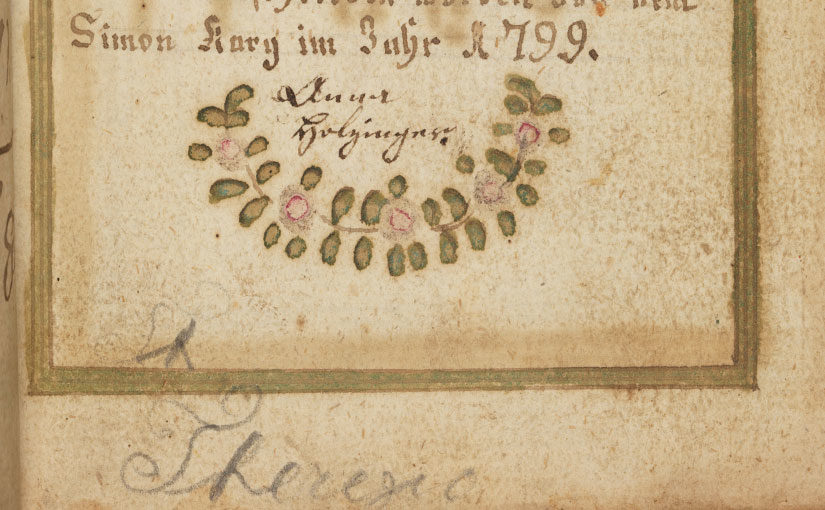

…sich befinden in Andachtübung Gott deß Morgens, und Abends, bey den Heiligen Meß, Beicht und Kommunion Gebettern zu sprechen. Wie auch unterschiedliche Getbetter zu Christo, und Maria, auf die fürnehmsten FestTage deß Jahrs. Und auch Gebetter zu dem Heiligen Gottes zu finden sein. Zu grössern Ehr und Seelen Trost. Geschrieben worden von dem Simon Kary im Jahr 1799.

..they are [for] devotional practice to pray to God in the morning and in the evening, at the Holy Mass, confession and communion prayers. As well as different prayers for Christ and Mary on the most noble feast days of the year. And prayers to the Holy of God can also be found. To greater honor and consolation to souls. Written by Simon Kary in 1799

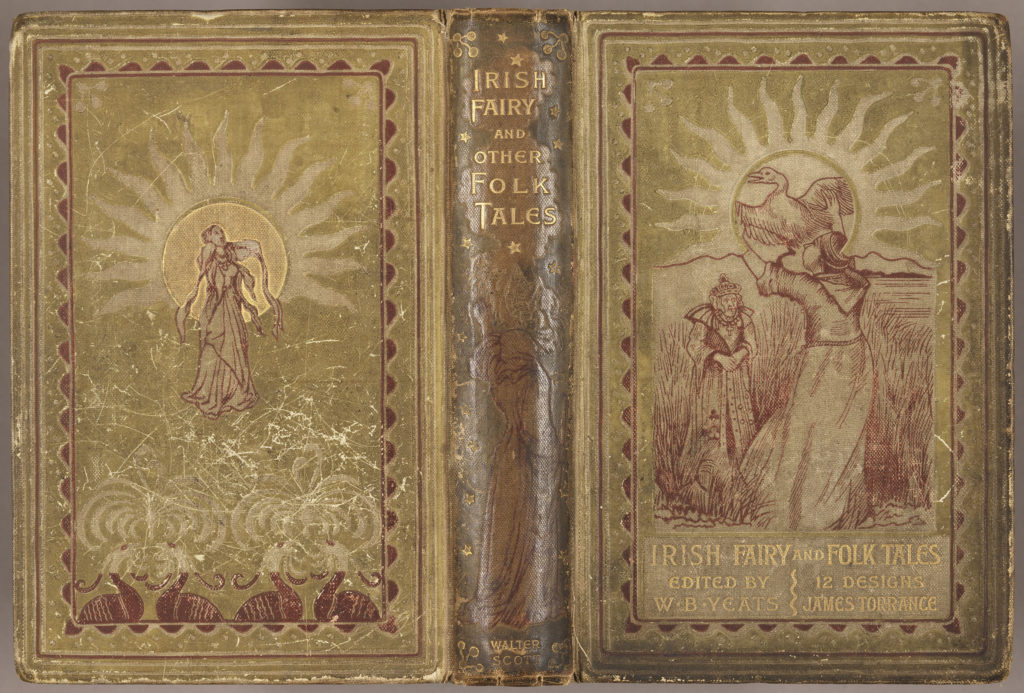

Simon Kary wrote his prayer book in the style that was current in the “Pennsylvania Dutch” region, a typical German-American fraktur style, including beautiful floral decorations and lettering. The 136-page manuscript even has its original block-printed paper wrappers, which shows that people took some care of it for over 220 years. The small book certainly had use, as smudges, dirt, oil, and handwritten additions attest. Perhaps most poignant is the inscription from a 19th c. owner opposite the manuscript title page, which reads in translation: “Forget not your father and your mother, for they have died. My most honored father died on 17th March in the year of the Lord [1]784. My beloved mother died on 6th December in the year of the Lord [1]801. The 14th November in the year of the Lord [1]803. M.S. in the sign of the fish.”

Who owned this unique prayer book? First, Simon Kary in 1799; then “M.S.,” who added the note about parents inside the front wrapper by 1803; later there is an early-19th-century ownership signature of “Anna Holzinger” on the title-page, and a pencil signature of “Theresa” in the lower margin of the title page. It would be hard to tell the particular story of this manuscript prayer book with only these clues, but it is an exemplar of a tradition of writing.

Our bookseller notes that German-American Catholic fraktur prayer books are rare but not unknown; there is a nearly contemporary example in the renowned collection of fraktur at the Free Library of Philadelphia, which contains a “Himmlischer Palm Zweig Worinen die Auserlesene Morgen Abend Auch Beicht und Kommunion Wie auch zum H. Sakrament In Christo und seinen Leiden, wie auch zur der H. Mutter Gottes, 1787” (item no: frkm064000).

In 1799 the German population in the U.S. is estimated to have been between 85,000 and 100,000 individuals, the vast majority being Protestants of one stripe or another. German Catholics were a very small minority, and concentrated in Pennsylvania. A 1757 count of Catholics in Pennsylvania, both Irish and Germans, compiled from several sources, totalled only 1365 people. Pennsylvania German Catholics were served first by Jesuits sent from Maryland, where half the population was Catholic. German Jesuit missionaries established the mission of The Sacred Heart at Conewago (circa 1720) and Father Schneider’s mission church in Goshenhoppen (circa 1740). There was also a tradition of fraktur birth and baptismal certificates among Protestants and Catholics in this era. Nevertheless, the Kary prayer book now in the Hesburgh Library is exceptionally rare.

Our bookseller, Philadelphia Rare Books & Manuscripts Company, stated that “There were no German-language Catholic prayer books published in the U.S. until the 19th century, so those wishing to have one before then had to have a bookstore import it or engender one in manuscript.”

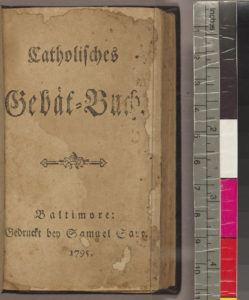

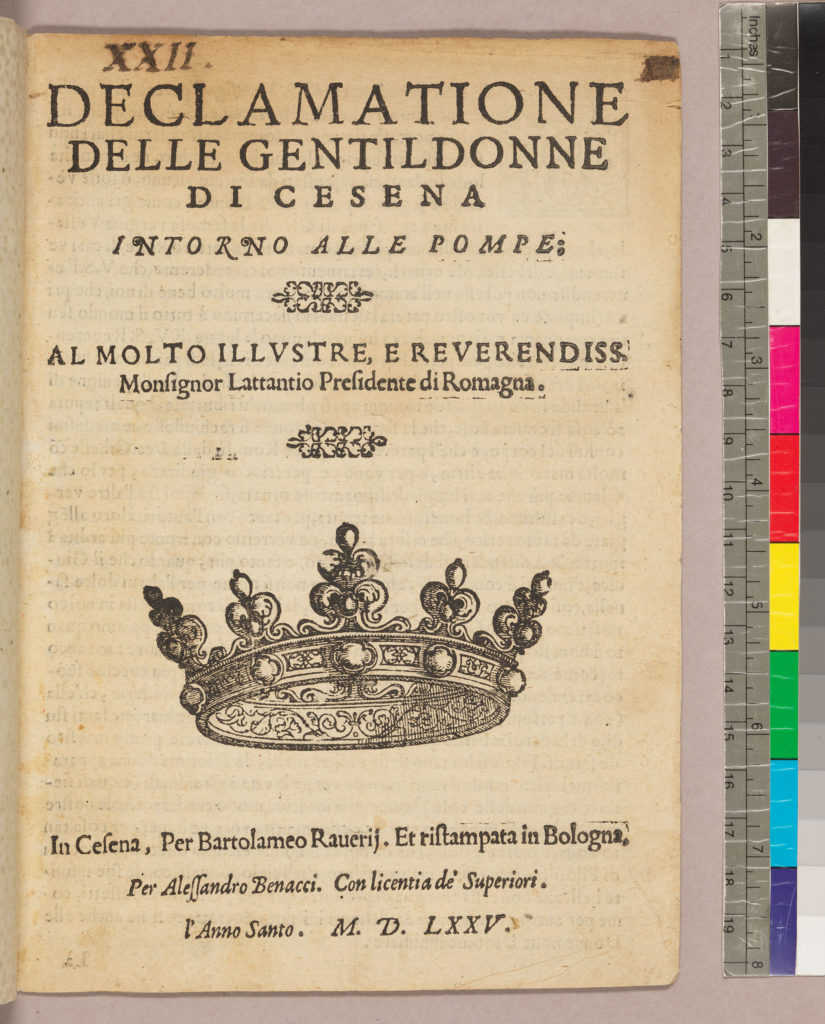

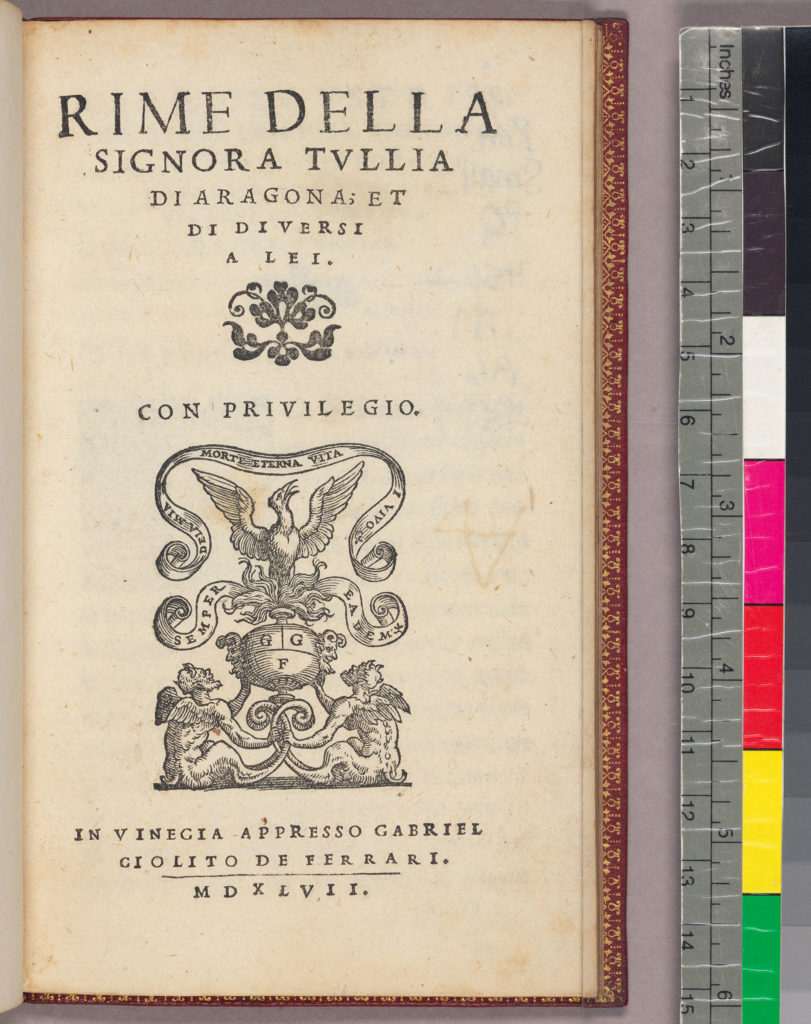

However, we have a fine example of a German Catholic prayer book, printed in Baltimore in 1795 by Samuel Saur (1767-1820). Saur was a grandson of the Philadelphia (Germantown) printer Christopher Sauer (also Sower), famous for printing the whole bible in German in 1743. That 1743 bible was the translation of Martin Luther, and the Sauers were not Catholics. Printers such as the Irish immigrant Mathew Carey (arriving in Philadelphia in the 1780s) and later generations of Sauers, printed all manner of Catholic, Protestant, and secular materials, in a number of languages.

Samuel Sauer began his working life in Germantown, but eventually moved to Baltimore, where he advertised his unique-to-the-city skills of printing in English and German. One of his early Baltimore imprints was the Catholisches Gebät-Buch, published the year he set up shop in the city. Over the course of his 25 years in Baltimore, Saur printed a number of Catholic titles in German, as well as many Pietist works, almanacs, and newspapers. Certainly his location in Catholic Baltimore gave him the commissions for things Catholic, and the relative proximity of Baltimore to Pennsylvania gave him access to most of the German readers in the U.S.

The Simon Kary German prayer book of 1799 likely represents the middle to end of the era of the self-made manuscript for Catholic devotional purposes, while the Catholisches Gebät-Buch of Samuel Saur shows the arc of the German language printers accommodating the differing religious affiliations of the German immigrants, in order to make a living. There remain many questions to ask about the particular prayers contained in these two works, and questions about their Catholic readers.

Thanks to the Philadelphia Rare Books & Manuscripts proprietors for sharing their research with us.

For further information, see the articles below:

The Catholic Church in Colonial Pennsylvania, by Sister Blanche Marie

(Convent of St. Elizabeth, Convent, NJ). Pennsylvania History, vol. 3, no. 4, October 1936, pp. 240-258.

Durnbaugh, Donald F. “Samuel Saur (1767-1820): German-American printer and typefounder.” Society for the History of the Germans in Maryland, vol. 42nd Report, 1993, pp. 64-80.