By Joyce Rivera González, Ph.D. Candidate, Department of Anthropology

Although Puerto Rico’s current two-party system might seem familiar to those interested in the American political landscape, Puerto Rican political parties are not necessarily defined by fiscal and/or social liberalism or conservatism, but instead by their views on the future political status of the archipelago. The two main political parties are the New Progressive Party (PNP), which seeks Puerto Rico’s full annexation into the Union as its 51st state, and the Popular Democratic Party (PPD), a party which designed and implemented the current political system of the Estado Libre Asociado (loosely translated as “Commonwealth,” but literally translated as “Free Associated State”).

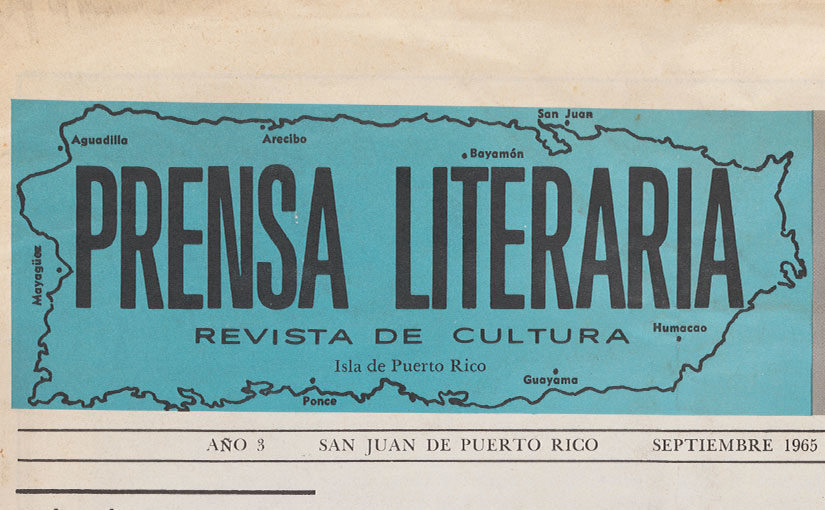

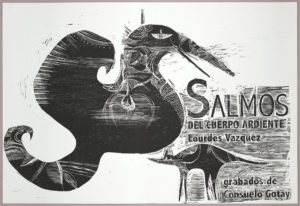

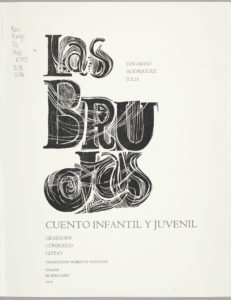

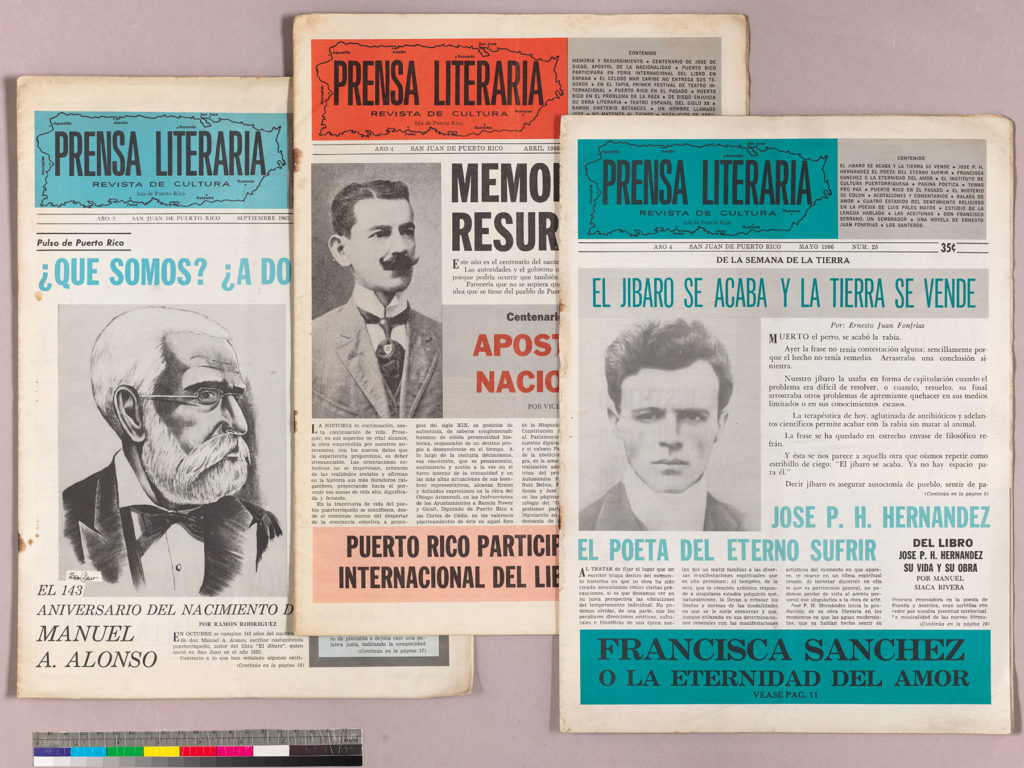

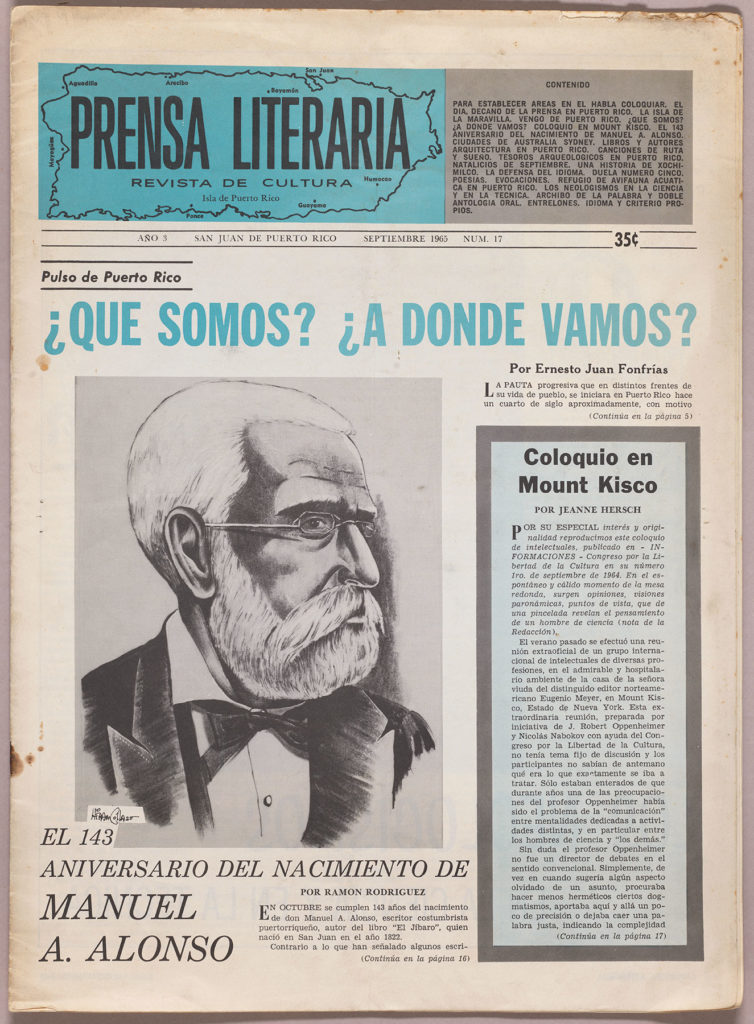

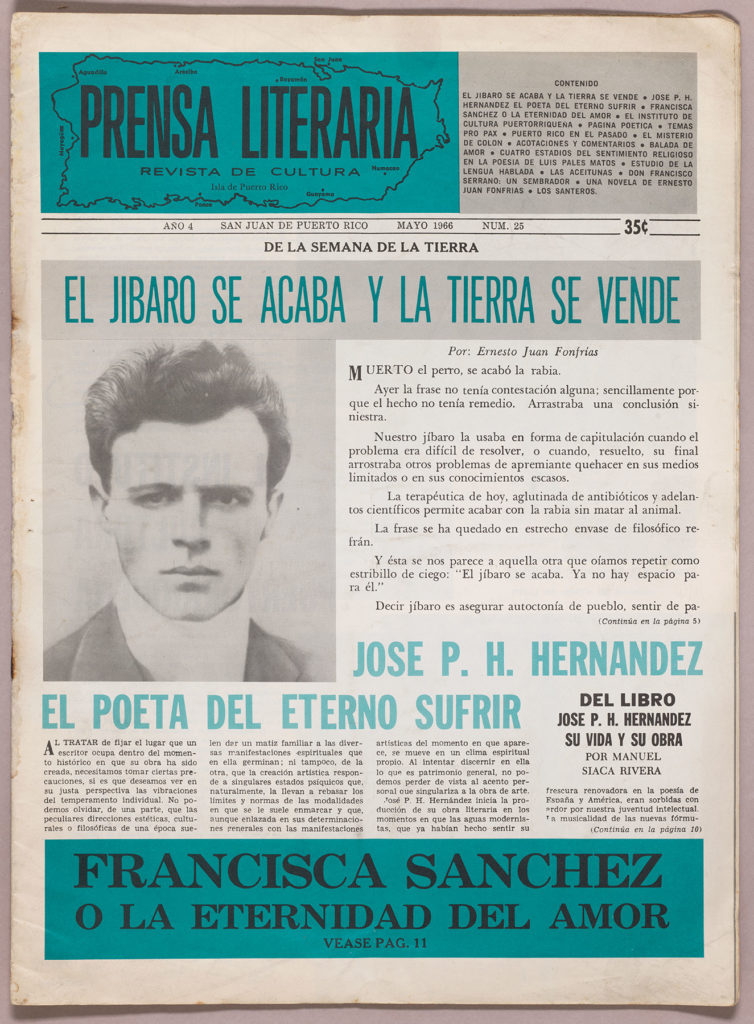

Rare Books and Special Collections’ Puerto Rican holdings include 27 issues of the periodical Prensa Literaria: Revista de Cultura. Dating from 1963 to 1966, this magazine highlights key debates and tensions in the development of Puerto Rican politics and identity following the new Constitución del Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, ratified in 1952.

WHO ARE WE? WHERE ARE WE GOING?

Prensa Literaria was edited by major literary and political figures in Puerto Rico, many of whom were affiliated with the PPD.

The PPD was a pivotal player in the postwar transformation of Puerto Rico. The party’s leader, Luis Muñoz Marín, was dubbed the architect of a new Puerto Rico and became the first democratically-elected governor of the archipelago in 1948, a role he held for 16 years. His political magnum opus was Operación Manos a la Obra (Operation Bootstrap), a massive industrialization political programme that began in 1947 and would transform the Puerto Rican economy, society, and political landscape in the years to come. For the average working-class poor, weekly wages more than doubled, life expectancy rose from 46 to 69 years, and basic living standards and infrastructure would vastly improve for all Puerto Ricans between 1953 and 1963 (see Ayala & Bernabe, 2007). Yet many of the PPD’s projects also depended on manufacturing incentives for US-based corporations, which dramatically reshaped the economy of the territory and broader Caribbean, detrimentally limiting economic and political self-sufficiency to the region.

The whirlwind of change and industrialization that characterized the 1950s on the archipelago created what many scholars have identified as a collective existential crisis of sorts. This is reflected in an editorial by Ernesto Juan Fonfrías that appears in the September 1965 issue of Prensa Literaria, entitled, Who/what are we? Where are we headed? Fonfrías, a scholar, writer, and one of the founding members of the PPD, muses,

Many aspects of Puerto Rican life have not yet acclimated to the momentum of progress that has come to provide its benefits, almost all of a sudden but in times of crisis, because it met an unprepared average citizen, orphaned from moral, educational, and religious values, which are necessary to any civilized man’s wellbeing […] The result of economic progress has impaired the individual’s moral capacity to be and feel.

Muchos renglones de la vida puertorriqueña no se han atemperado al impulso de progreso que vino a regar sus parabienes, casi súbitamente pero en momentos de apuros, porque encontró al ciudadano promedio impreparado [sic], huérfano de muchos de los valores morales, educativos, y religiosos que son necesarios en el haber de todo hombre civilizado […] El producto del progreso económico ha dañado la capacidad moral del individuo para ese alto estar y sentir.

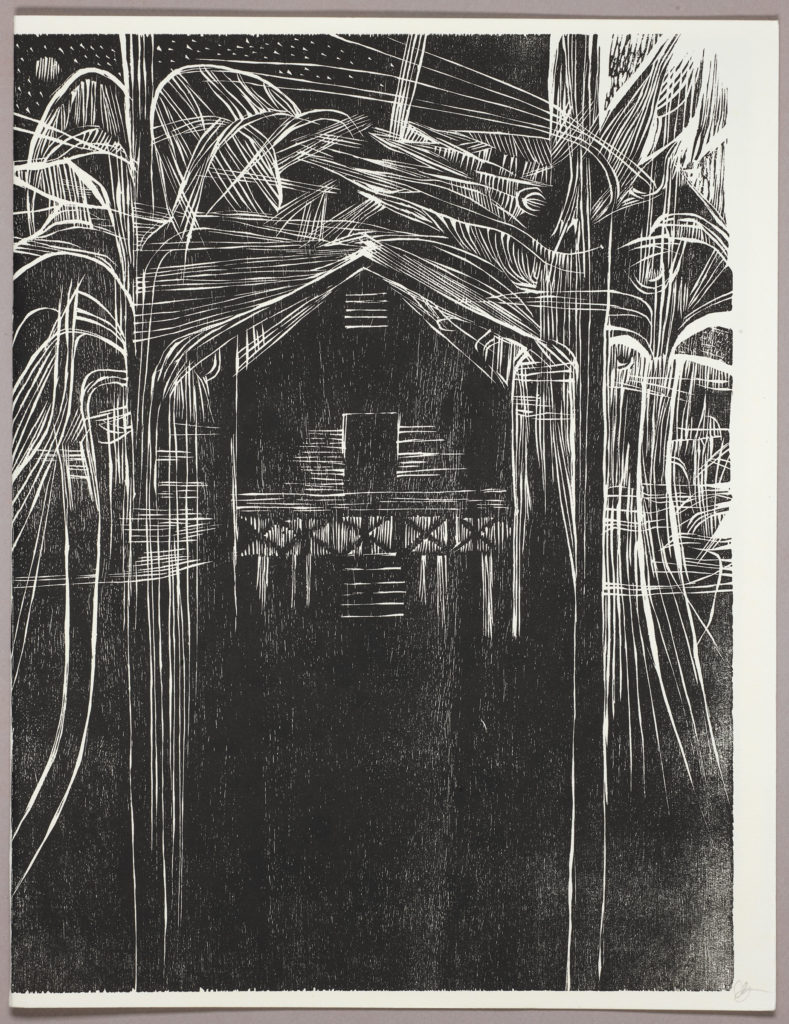

THE JÍBARO IS GONE, AND THE LAND IS UP FOR SALE

In his front-page editorial “El jíbaro se acaba y la tierra se vende” (“The jíbaro [rural peasant] is gone and the land is up for sale”) in the May 1966 issue of Prensa Literaria, Fonfrías further examines Puerto Rican identity during an era of change.

Perhaps the jíbaro is disappearing from the countryside, but his mark on history will remain, his criollo lifestyle, his cultural heritage and his milestone in civilization, which shall never be forgotten […] Who knows? Maybe the more civilized we become, the more jíbaro we become in our love for the land! […] Progress is good and so is the jíbaro.

Tal vez el jíbaro desaparezca de la ruralía, pero quedará su quehacer histórico, su criollo vivir, su acervo de cultura y su hito de civilización que no se olvidarán […] Quién sabe si mientras más civilizados, seguimos siendo más jībaros en el amor a la tierra! […] El progreso es bueno y el jíbaro lo es también.

Fonfrías takes on the very ideal of cultural nationalism—the jíbaro—in this passage. Through his seemingly benign, yet arguably patronizing discussion, he approaches the quandary (paradox, for some) that stood at the very core of the PPD ideology: ¿y no podrá haber progreso y jíbaro también? (“could there not be both progress and jíbaros, as well?”)

As in the previous issue, we see Fonfrías struggling to reconcile economic changes (“progress”) and industrialization with social and cultural realities and ideals. These debates intersected with conversations regarding the archipelago’s political status. In its early days, even under Muñoz Marín, the PPD supported independence, but this stance slowly and quietly eroded. Prensa Literaria best captures the centrist positioning of the political status quo that emerged as a result of the PPD’s political evolution, still in effect to this day.

REFERENCIAS

Agrait Betancourt, Luis. “La idea independentista de Luis Muñoz Marín (1913-1931).” In Luis Muñoz Marín: ensayos del centenario. Edited by Fernando Picó, 1-15. San Juan: Fundación Luis Muñoz Marín, 1999.

Ayala, Cesar y Rafael Bernabe. Puerto Rico in the American Century: A History since 1898. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Cortés Zavala, María Teresa y María Magdalena Flores Padilla. “La Revista Puertorriqueña: el periodismo cultural y sus redes hispanoamericanas.” Revista de Indias 75, no. 263 (2015): 149-76.

Díaz Quiñones, Arcadio. El arte de bregar: ensayos. San Juan: Ediciones Callejón, 2000.

Duprey Salgado, Néstor R. Independentista popular: las causas de Vicente Géigel Polanco. San Juan: Crónicas Publicaciones, 2005.

Grosfoguel, Ramón, Frances Negrón-Muntaner, and Chloé S. Georas. “Beyond Nationalist and Colonialist Discourses: The Jaiba Politics of the Puerto Rican Ethno-Nation.” In Puerto Rican Jam: Rethinking Colonialism and Nationalism, pp. 1-38. Edited by Frances Negrón-Muntaner & Ramón Grosfoguel. Minneapolis & London: University of Minnesota Press, 1997.

Pantojas-García, Emilio. “Puerto Rican Populism Revisited: the PPD during the 1940s.” Journal of Latin American Studies 21, no. 3 (1989): 521-557.

Serra Collazo, Soraya. “Explorando la Operación Serenidad.” In Explorando la Operación Serenidad, pp. 7-10. Edited by Soraya Serra Collazo. San Juan: Fundación Luis Muñoz Marín, 2011.