Please join us for the following events being hosted in Rare Books and Special Collections:

Tuesday, September 5 at 4:00pm | Opening reception for the fall exhibit, Elements of Humanity: Primo Levi and the Evolution of Italian Postwar Culture. This exhibit is curated by Tracy Bergstrom (Curator, Italian Imprints and Dante Collection) and opens on August 21.

Friday, September 15 at 4:00pm | Dedication program for Emily Young’s sculpture Lethos, to be followed by a reception in the Carey Courtyard View Area (Second Floor – Hesburgh Library). Sponsored by the Hesburgh Libraries and the Alumni Committee for Poetry and Sculpture.

Thursday, September 21 at 5:00pm | The Italian Research Seminar: “Titian’s Icons” by Christopher J. Nygren (Pittsburgh). Sponsored by Italian Studies at Notre Dame.

The monthly spotlight exhibit for September is The Art of Botanical Illustration: Philip Miller’s Gardeners Dictionary.

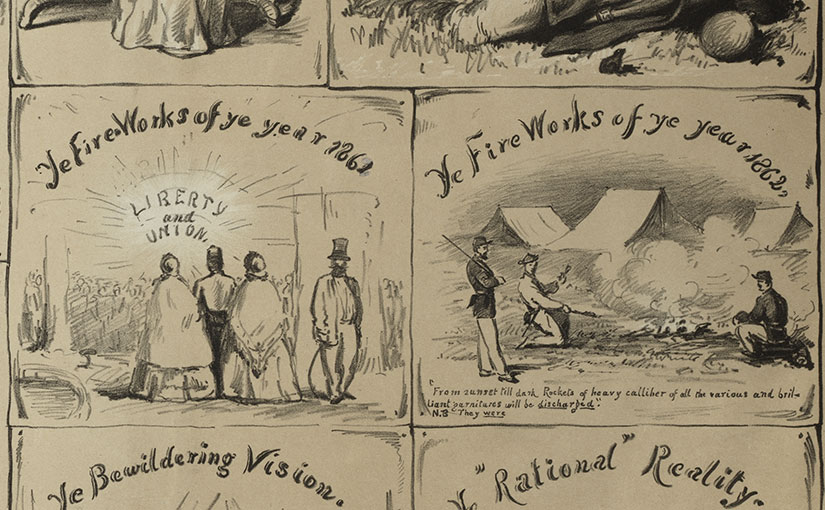

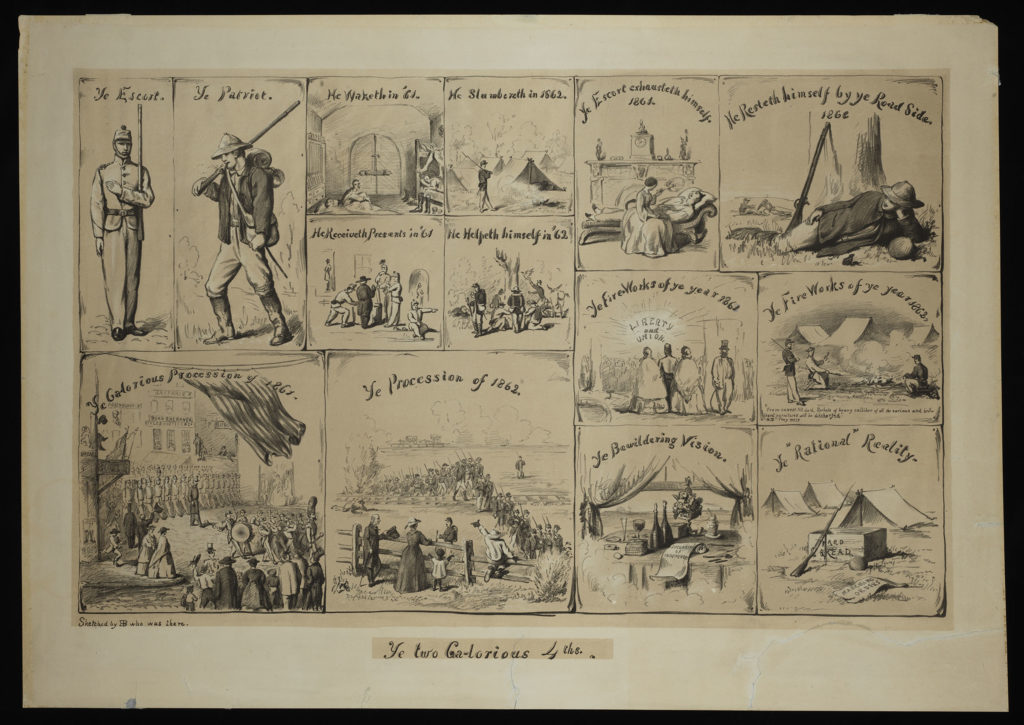

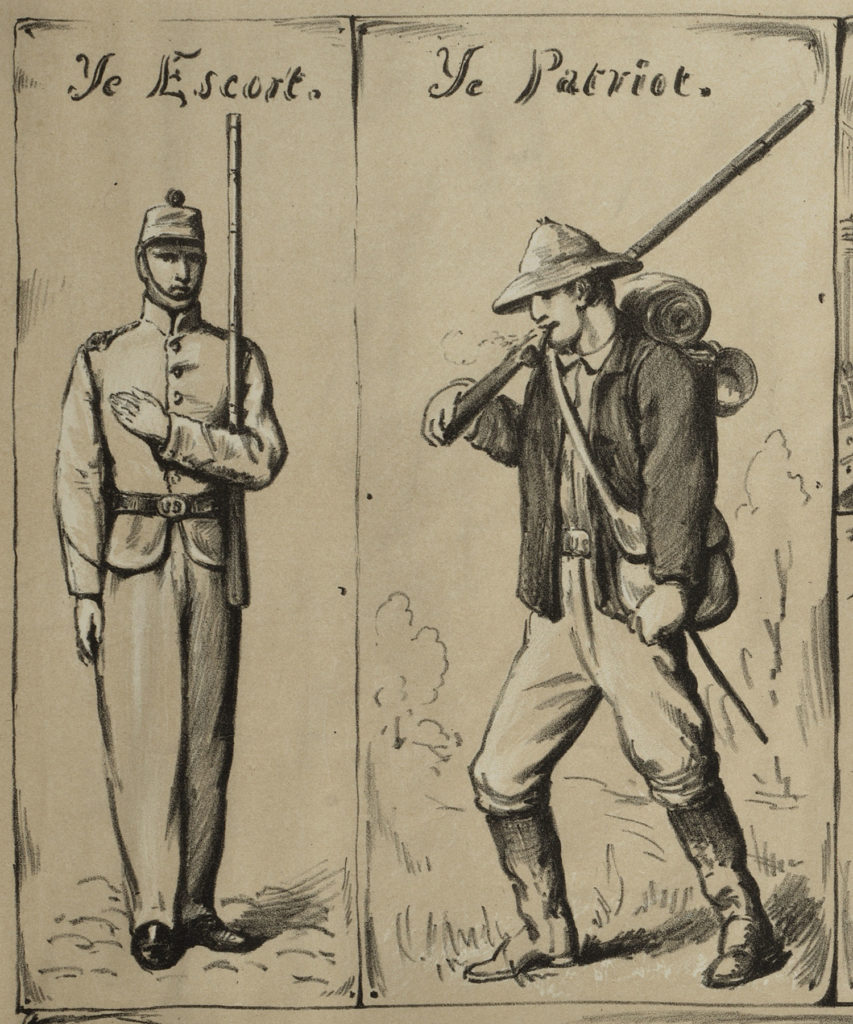

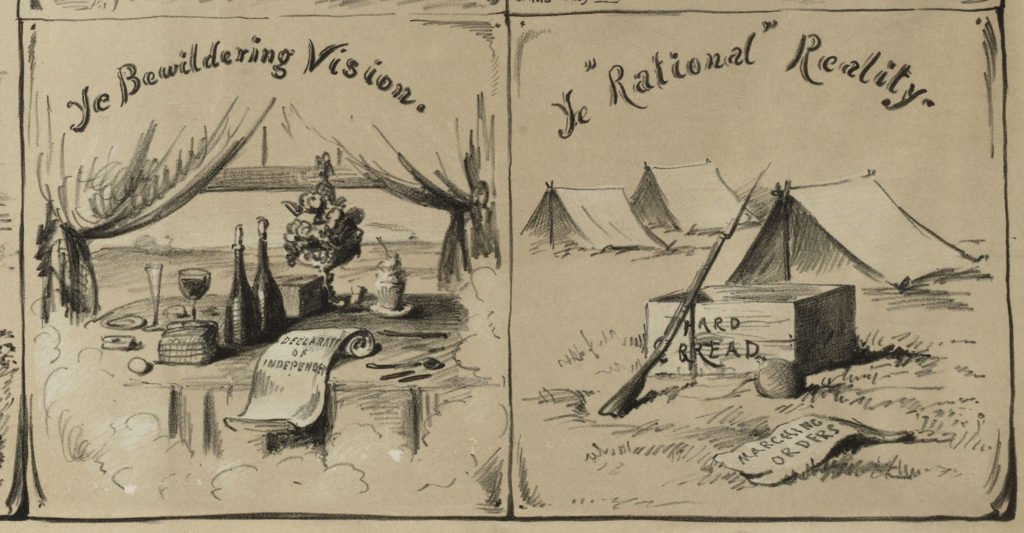

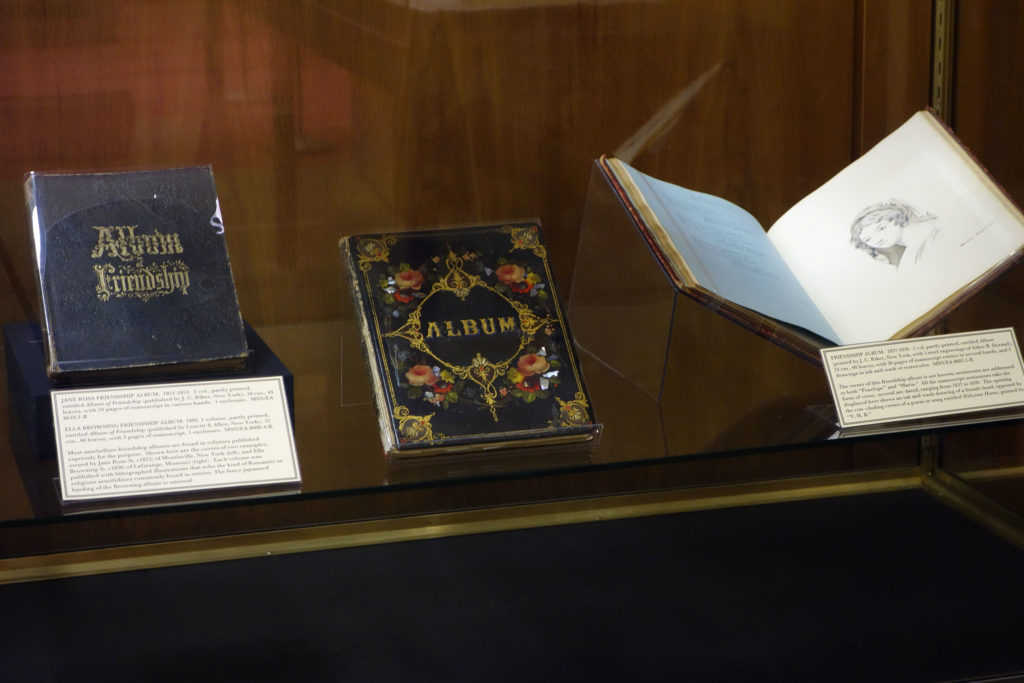

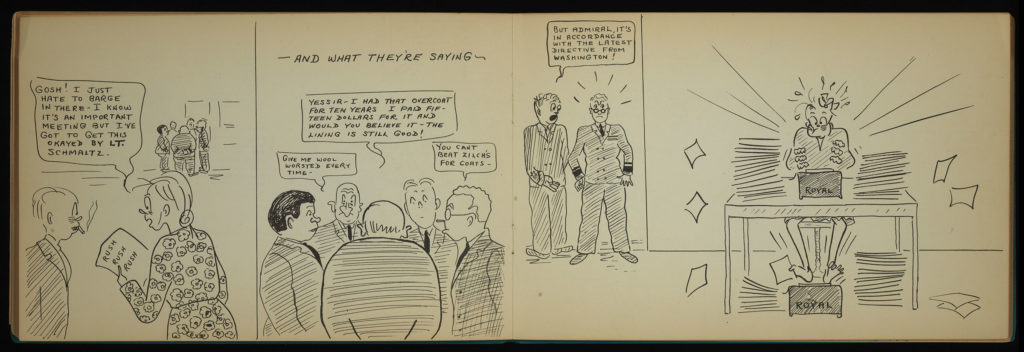

The summer spotlight exhibit, “Which in future time shall stir the waves of memory” — Friendship Albums of Antebellum America, continues to be on display through September and features seven volumes from Special Collections’ manuscripts of North America holdings.