by Anne Elise Crafton, PhD, RBSC Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Hesburgh Libraries

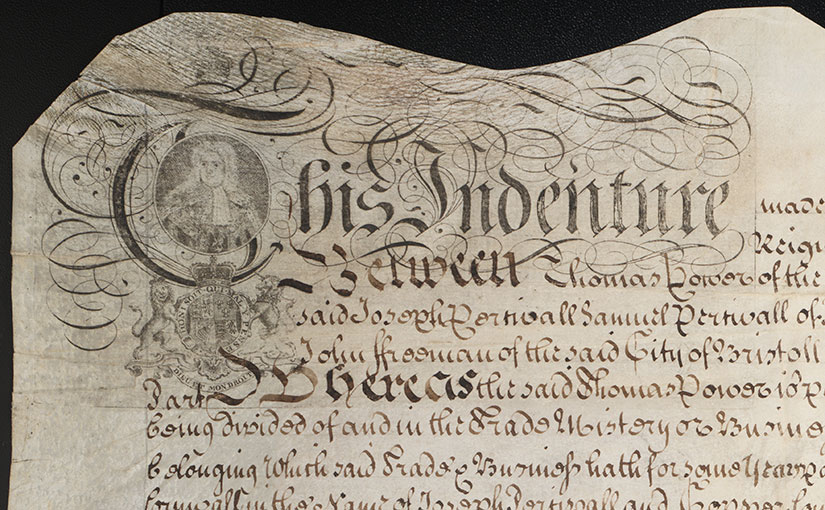

Although I am trained primarily as a scholar of the medieval world, much of my time as the 2024-2025 Rare Books and Special Collections Postdoctoral Research Fellow has been preoccupied by the early modern documents within the Hesburgh Library’s collection. Among this material is the White Rock Copper Works Shares Collection, which consists of several “assignments of shares”—documents which recorded the transfer of shares or capital—for an eighteenth-century copper cooperative in Bristol and Swansea, UK. Under various names—including the Thomas Coster and Co. (1736/7-1739), the Joseph Percivall and Copper Co. (1739-1764), and the John Freeman and Copper Co. (1764-)—the merchant cooperative operated the White Rock Copper Works, a copper smelting firm in Pentrechwyth (near Swansea). On the surface, the items in this collection simply record the finances of a copper collective during the first 45 years of its existence. When appropriately contextualized, however, this collection testifies to the ubiquity of the Transatlantic Slave Trade in contemporary British markets.

The nineteen items in this collection document the notable growth of the copper cooperative from its creation under Thomas Coster in 1737 until 1781, at which point the controlling interest was held by John Freeman Sr. The financial success of the copper cooperative cannot be understated. In its first year of operation a single share in the cooperative was worth £297 (£56,563 today), but by 1781 a single share was worth £2000 (£266,208, or $345,055 today)!

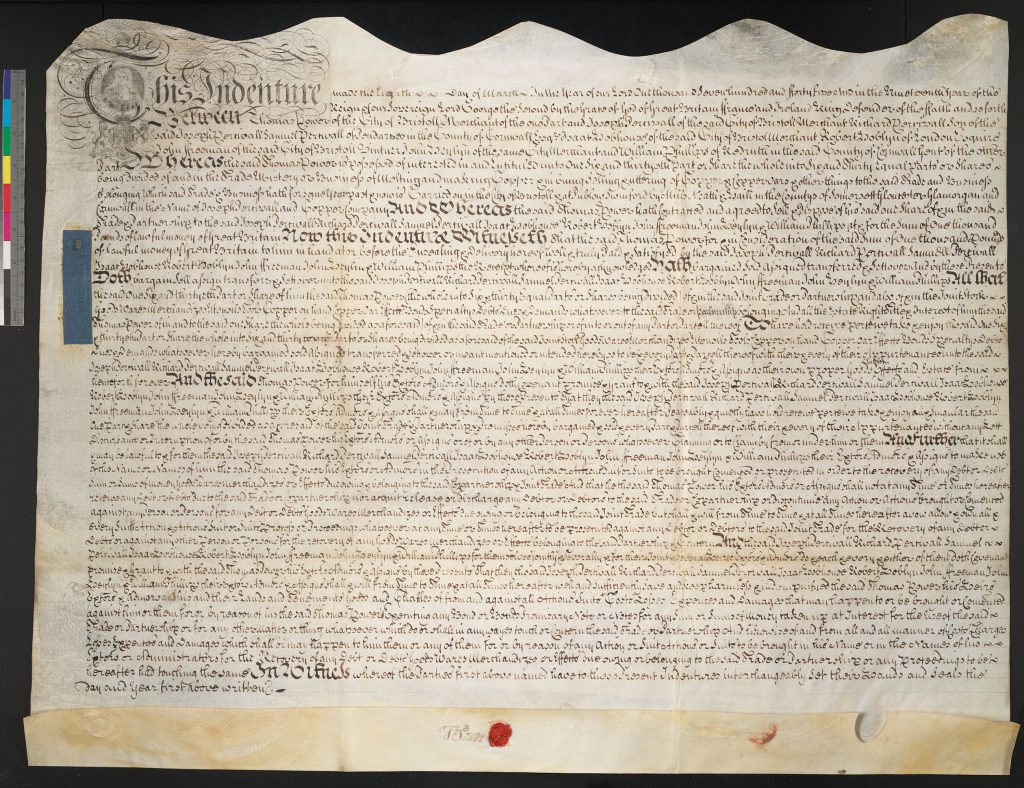

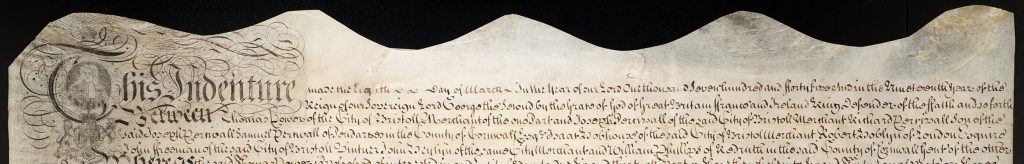

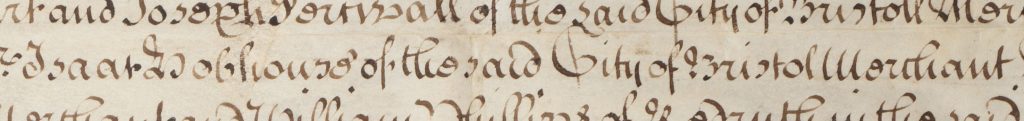

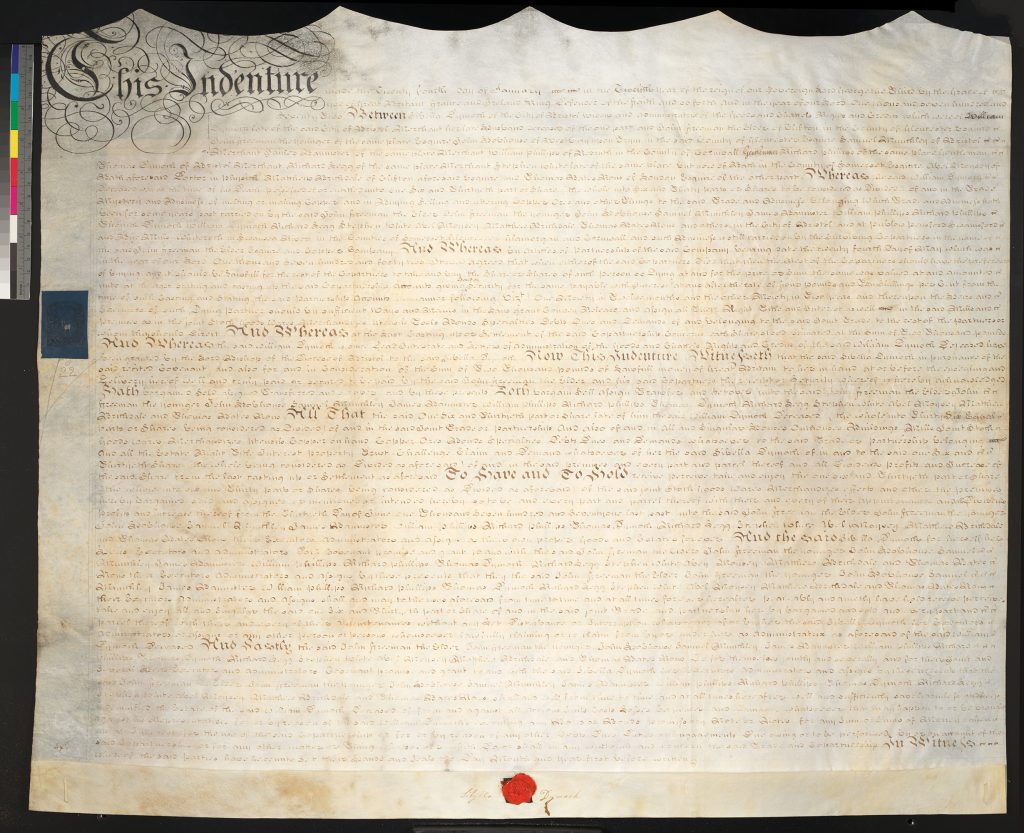

As physical objects, these items are both imposing and underwhelming. They are quite large—most of the parchment documents are approximately 680 x 825 mm (around 2 ¼ x 2 ⅔ ft)—but textually simple. Each document lists the parties involved individually and multiple times (including each member of the copper cooperative at the time of sale), the exact nature of the sale, and the binding nature of the sale in exhaustive and dull legal language.

Nowhere in this exhaustive language, however, is there any mention of the primary force behind the collective’s financial success: the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

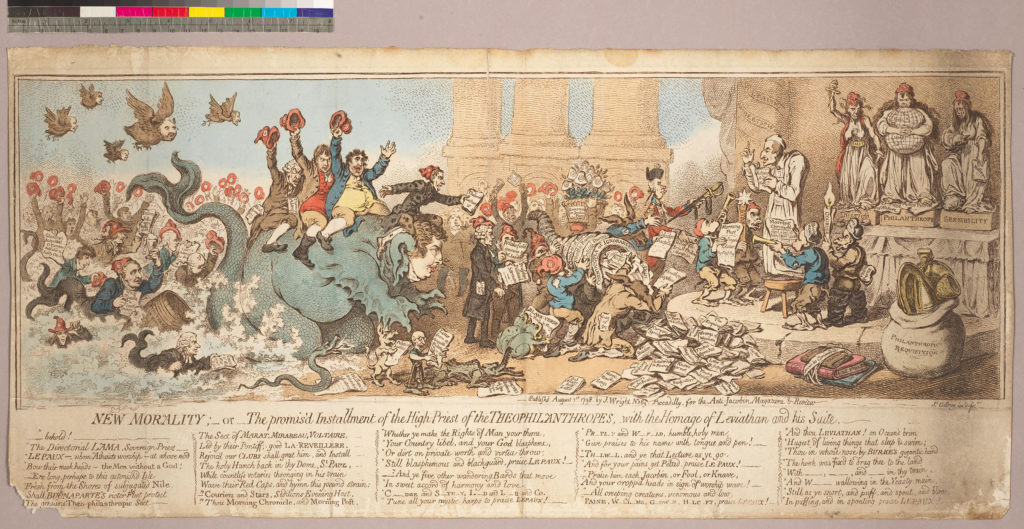

In the eighteenth century, Bristol was “the slave capital” of Britain’s triangular trade. The port, which in 1755 had 237 slave traders, sent thousands of ships full of manufactured goods to Africa, which brought enslaved Africans (purchased with said goods) to the Americas and returned to the city with the products of slave labor. Every Bristol industry profited from this trade, but the copper industry especially so. Copper products—many of which were produced by the copper collective and the White Rock Copper Works—were favored in nearly every theater of the global slave trade. Copper rods were used to purchase enslaved Africans in West Africa, copper products were used to refine sugar in West Indies plantations, slave and merchant ships had copper-plated bottoms to withstand tropical waves, and copper luxury goods were sold around the world to fund Britain’s colonial control. In other words, it is no coincidence that a copper cooperative in Bristol would see such financial success.

Through the data made available by the Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery and the collaborative database Bristol and Transatlantic Slavery, I was able to identify several partners in the copper cooperative named in this collection as active participants in the triangular trade. For instance, the document, “Assignment of Shares, Thomas Power to Joseph Percivall and Copper Co., 1746-03-08 (MSE/EM 3700-2)” (seen above) lists an Isaac Hobhouse (d. 1763) as a member of the Bristol copper cooperative. Like many of his fellows, his occupation is listed innocently as “merchant.” More accurately, though, Hobhouse’s primary occupation was “slave trader”, with 68 recorded voyages on the Transatlantic Slave Trade between 1722 and 1747.

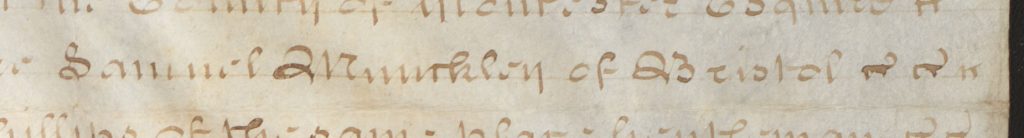

Another member of the cooperative, Samuel Munckley (1720-1801) (highlighted above in MSE/EM 3700-8), is listed on twelve documents. Like Hobhouse, the designation of “merchant” obscures Munckley’s role as a slave trader and profiteer in the West Indies. Munckley’s own ships were used to bring enslaved peoples from Africa to the West Indies, where many were sold as laborers on sugar plantations—an industry in which Munckley was also heavily invested. (See also “Bristol and Transatlantic Slavery”, which has compiled dozens of Munckley’s papers and correspondence as they relate to the slave trade.)

As I have said: nowhere in the White Rock Copper Works Shares is the slave trade explicitly mentioned. The collection is, at first glance, innocuous to the point of boredom. Yet this does not negate the fact that the wealth described in this collection was gained through an industry which itself relied on the trade of enslaved peoples. For this reason, when creating the finding aid for this collection, I deliberately included the names of each individual listed on the documents (parties involved, partners in the cooperative, and witnesses). No matter the degree to which these historical figures actively participated in the Bristol slave trade, each individual named in this collection profited from the enslavement of others and for this reason, their legacy—as a part of this archive—must be made explicit.

Several of the documents in this collection name women as economic actors—whether as sellers of shares, buyers, or witnesses. Although most of these transactions concern widows selling shares formerly owned by their deceased husbands back to the copper cooperative (like the above Sibylla Dymock of MSE/EM 3700-8, who sold her husband’s share back to the cooperative in 1772), their presence in these documents necessarily complicates our reading. Simultaneously, these documents testify to the names and economic force of women whose lives, in many cases, have otherwise gone undocumented and, they also tangibly record the ways in which these women profited from the slave trade and colluded with prominent slave traders.

Works Cited:

“John Freeman and Copper Co.” Grace’s Guide to British Industrial History.

“Isaac Hobhouse.” Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery.

“Joseph Percivall and Copper Co.” Grace’s Guide to British Industrial History.

“Samuel Munckley.” Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery.

“Suppliers to the trade.” Discovering Bristol: Bristol and Transatlantic Slavery.

“White Rock Copper Works.” Grace’s Guide to British Industrial History.