by Anne Elise Crafton, Ph.D. Candidate, Notre Dame’s Medieval Institute

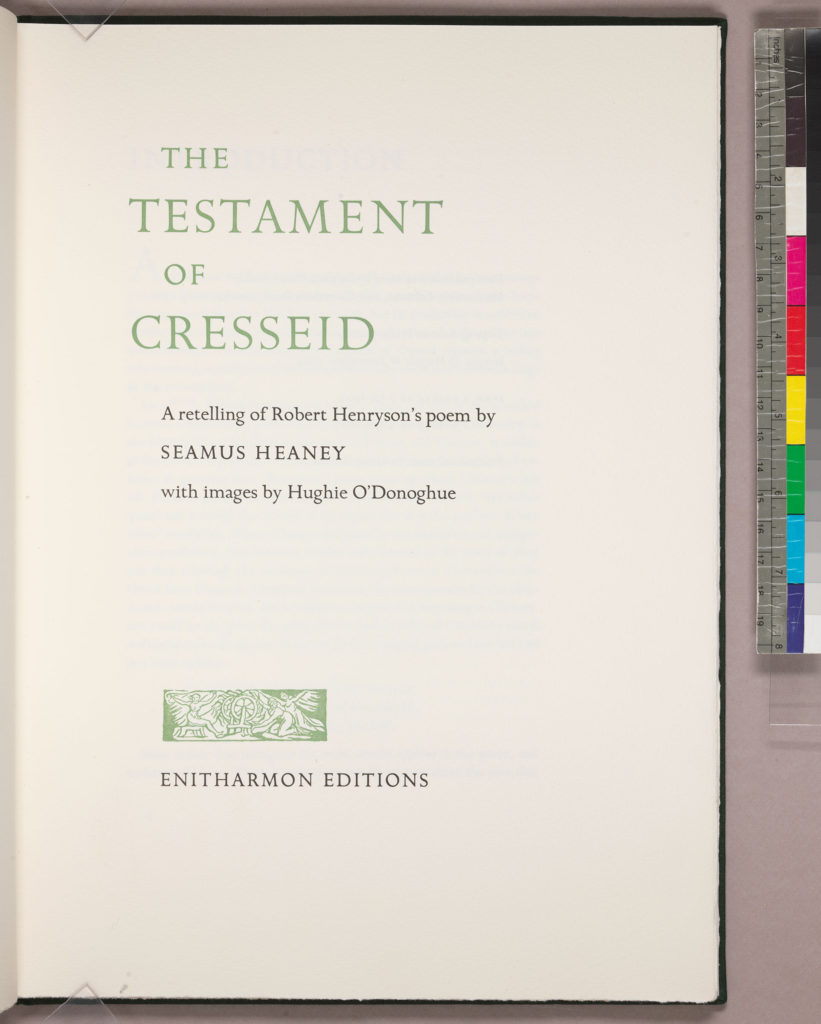

In addition to his original works, the Irish poet Seamus Heaney (1939-2013) is also known for his adaptations of ancient and medieval literature. The most famous of these is his translation of the Old English epic Beowulf, but he also adapted a lesser-known medieval poem, The Testament of Cresseid.

The Testament of Cresseid was composed by the 15th-century Scottish poet, Sir Robert Henryson. He was a part of a group of writers dubbed “The Scottish Chaucerians,” for their love of Geoffrey Chaucer (d. 1400), the author of The Canterbury Tales, a poem in Middle English. The Testament of Cresseid was Henryson’s direct response to Chaucer; in fact, it was meant to be a sequel to Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde, one of the first poems to use rhyme. This epic poem tells of the tragic love story of two Trojan youths during the Trojan War. Despite their love, Criseyde is given to the Greeks as a prisoner of war and takes another lover, the Greek warrior Diomedes. While Chaucer’s account ends here, Henryson adds a cruel fate for Criseyde: Diomedes abandons the beautiful Cresseid. The Trojan maiden cries out to the goddess of love, Venus, about her poor luck in love, but the goddess vengefully strikes her with leprosy and blindness. Cresseid goes to live among the beggars by the city gate, where the noble Troilus passes by; however, due to her blindness she cannot see him, and due to her deformity, he does not recognize her. Eventually when they do recognize each other, Cresseid regrets her treatment of Troilus and gives a mournful soliloquy then dies shortly afterwards.

Henryson’s poem was written in Middle Scots. This language, confusingly known as Inglis (English), is not the same as Middle English. Middle Scots was informed heavily by Irisch (i.e., Scots Gaelic not Irish) and maintains unique spellings such as substituting quh- for wh-, and ane for one, an, or a. For example:

Henryson’s Middle Scots (15th c.)

Ane doolie sessoun to ane cairfull dyte Suld correspond and be equivalent: Richt sa it was quhen I began to wryte This tragedie…

Heaney’s Modern English (21st c.)

A gloomy time, a poem full of hurt Should correspond and be equivalent. Just so it was when I began my work On this retelling…

Seamus Heaney cites three motives for his translation which distinguish it from others: the “advocacy for the work in question,” a “refreshment from a different speech and culture,” and “the pleasure of writing by proxy.” However, Heaney also admits in the preface that when he went to translate the poem, despite these grandiose motives, he found himself already stumped by the opening scenes. Both the complexity of Middle Scots and the phonetic power of Henryson’s verse were difficult to render into modern English, especially if Heaney wanted to retain the essence and feel of the original. However, the Middle Scots reminded Heaney of the Ulster-dialect of his family and as he continued his translation, he found himself “entirely at home” with Henryson’s poetry.

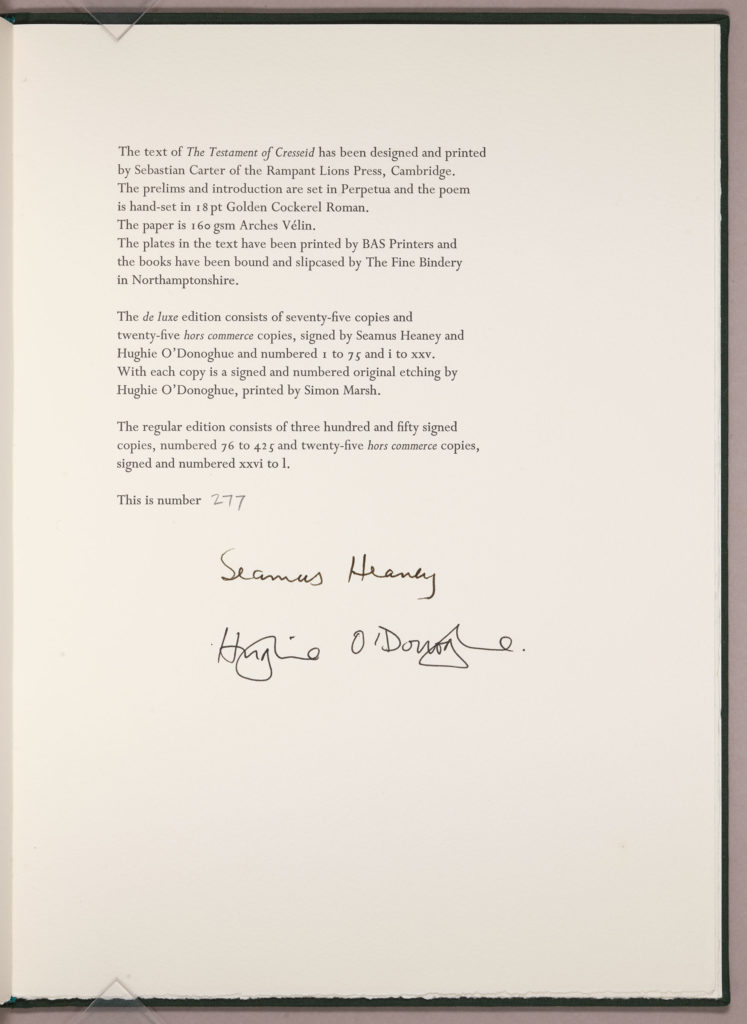

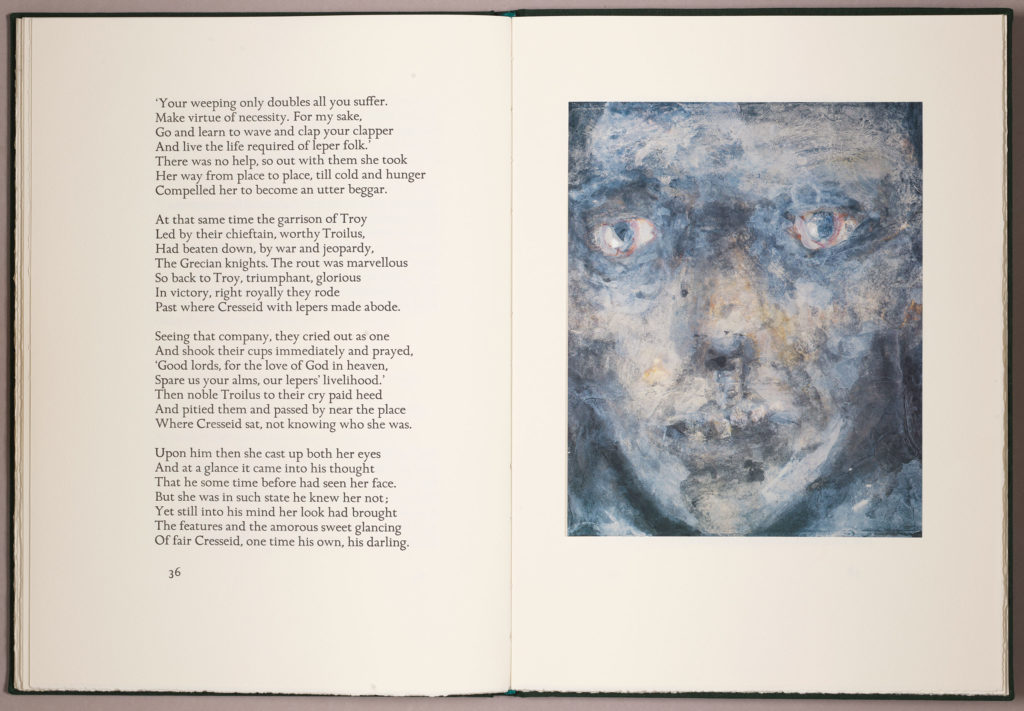

The Hesburgh Library owns the 2004 de luxe edition of The Testament of Cresseid signed by Heaney and illustrator Hugh O’Donoghue. Hugh O’Donoghue is an English artist known for exploring the universality of the human experience – a theme fitting for a poem so interested in love, loss, and fate. The deluxe edition does not include the Middle Scots text next to Heaney’s translation, unlike other editions. This situates Heaney as the sole access to the medieval past.

O’Donoghue’s paintings give the harsh poem an unexpectedly ethereal quality. The reader can revel in Cresseid’s legendary beauty, brought to life by O’Donoghue, and shudder at what she becomes in the end. By pairing O’Donoghue’s compelling art with Heaney’s translation, the edition fundamentally changes the experience of the poem. Altogether, the project expands beyond translation and continues a cycle of storytelling that transcends multiple languages, nationalities, and poetic traditions: Chaucer’s 14th-century English imagination of a mythic Mediterranean past, Henryson’s 15th-century Scottish response, and a 21st-century exploration of art, poetry, and memory by an Irish poet and English artist.