by Rachel Bohlmann, American History Librarian and Curator

Rare Books and Special Collections recently acquired a small archive that documents the Bonus Army—a Depression-era protest by World War veterans and their families. Lonore Kent (1907-1993), a journalist living in Washington DC at that time, created and assembled these sources.

In 1924, Congress had rewarded World War soldiers for their service with certificates of investment that would be payable by the government in 1945. By 1932, however, many veterans, like millions of Americans, were desperate after nearly three years of the nation’s disastrous economic depression. Former soldiers began to demand that President Herbert Hoover pay out the promised veteran bonus immediately, given the national (and global) crisis. The men’s plea caught the attention of people who thought the federal government should be doing more to address the economic depression and people’s real need. By the spring of 1932 legislation began moving through the House of Representatives’ Ways and Means Committee.

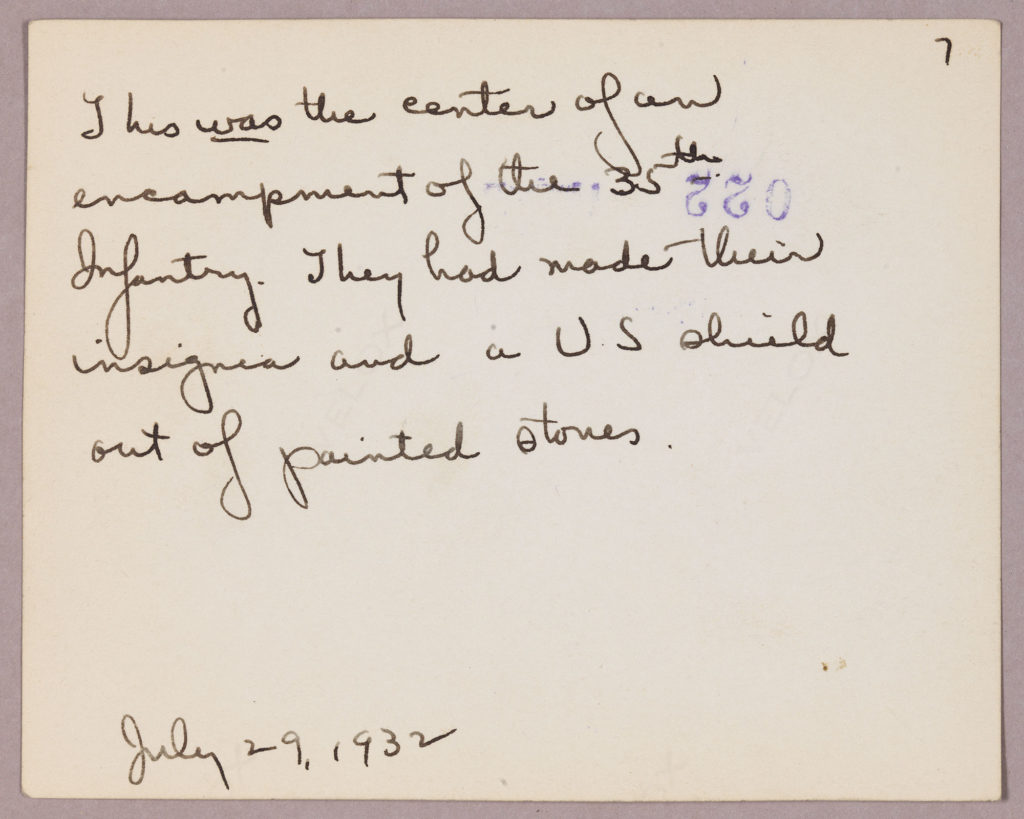

Some veterans, in a determined effort to put the case directly to their Congressional representatives, embarked for Washington. In early May, 300 former soldiers left Portland, Oregon, bound for the capital. Quickly dubbed the Bonus Army, they were joined by a trickle and then a river of veterans and their families nationwide. By June 40,000 Bonus Army marchers were in Washington; some huddled in makeshift shelter amid construction sites downtown, but the largest concentration of marchers settled on a muddy stretch of the Anacostia River, in an encampment of thousands of men, women, and children.

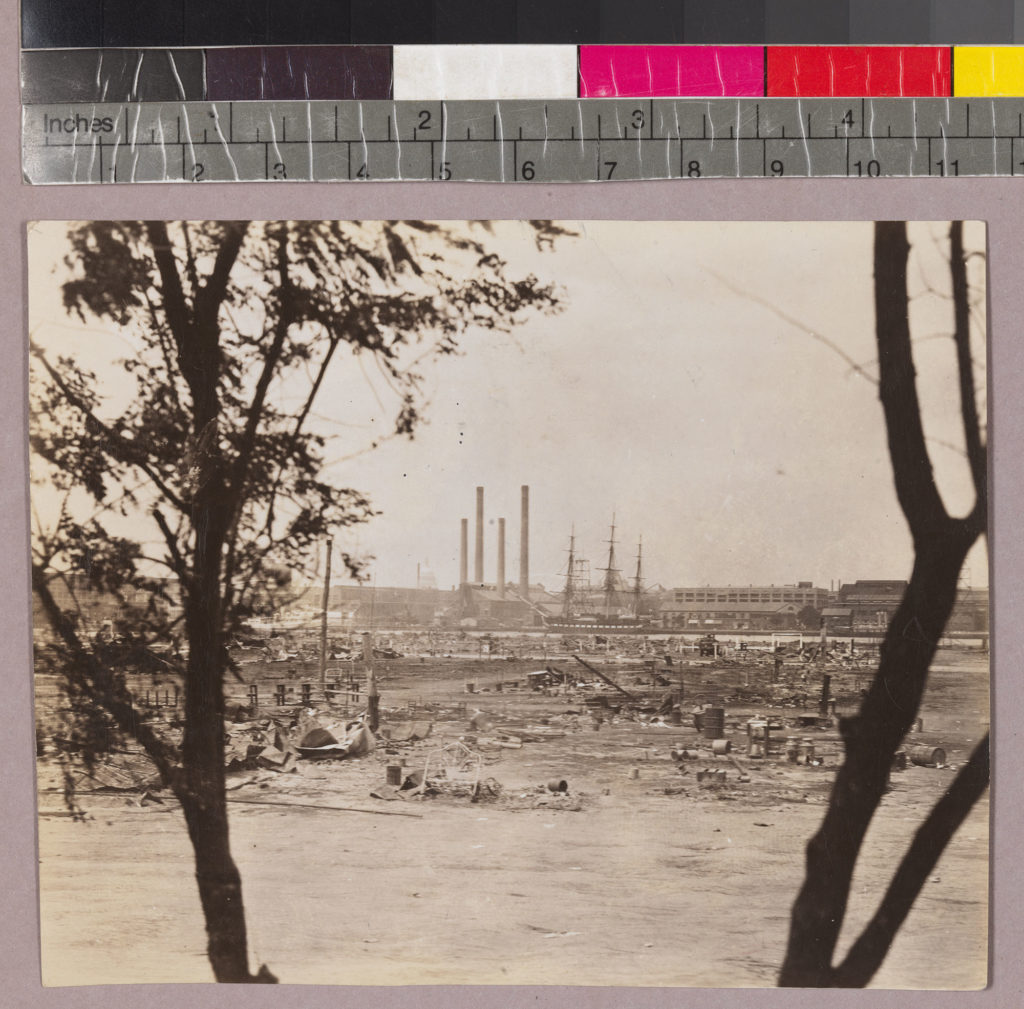

On June 15, 1932, the House passed enabling legislation, but the Senate blocked the bill two days later. This spared Hoover the embarrassment of vetoing it, which he had promised to do, citing budgetary constraints. Most Bonus Army members stayed put, hoping for some form of government relief. By the end of July, as Hoover looked to his re-election prospects in November, the President ordered city officials to disperse the Bonus Army. When some squatters resisted, Hoover called in US Army General Douglas MacArthur to restore order. MacArthur exceeded his instructions, however, using armed troops, tanks, and cavalry to drive Bonus Army families out of their shacks and tents, and burning the Anacostia River encampment to the ground.

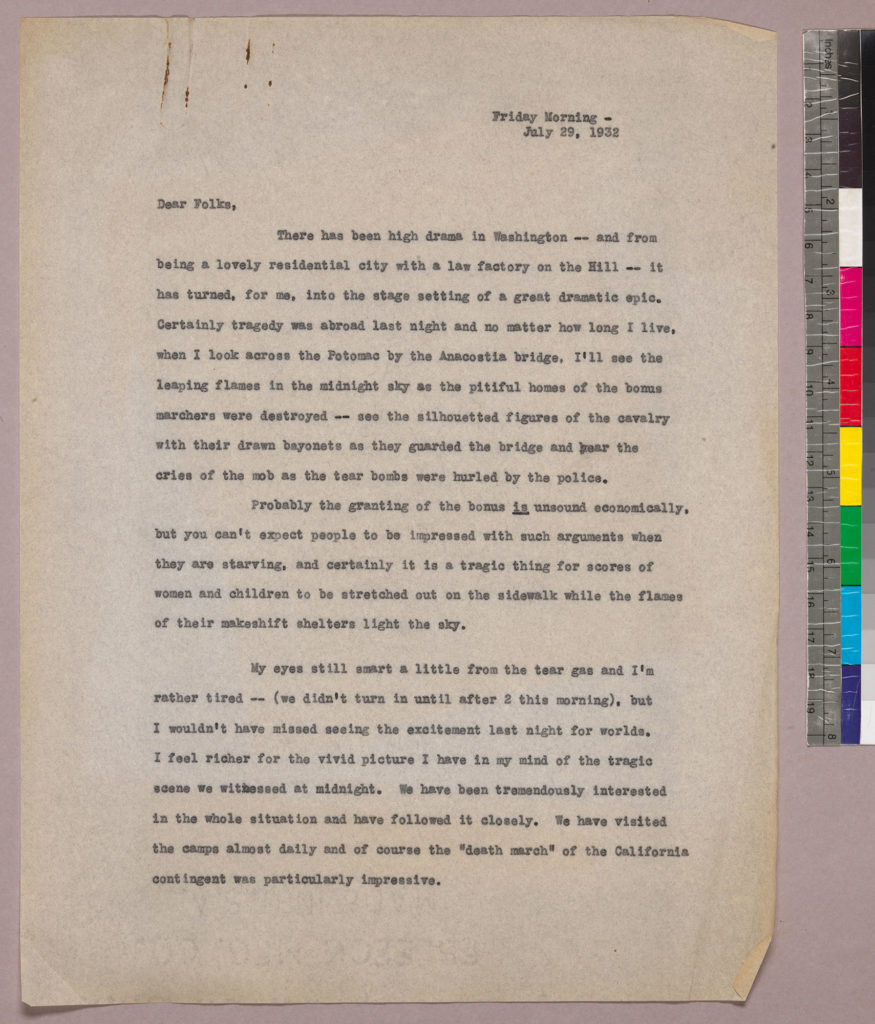

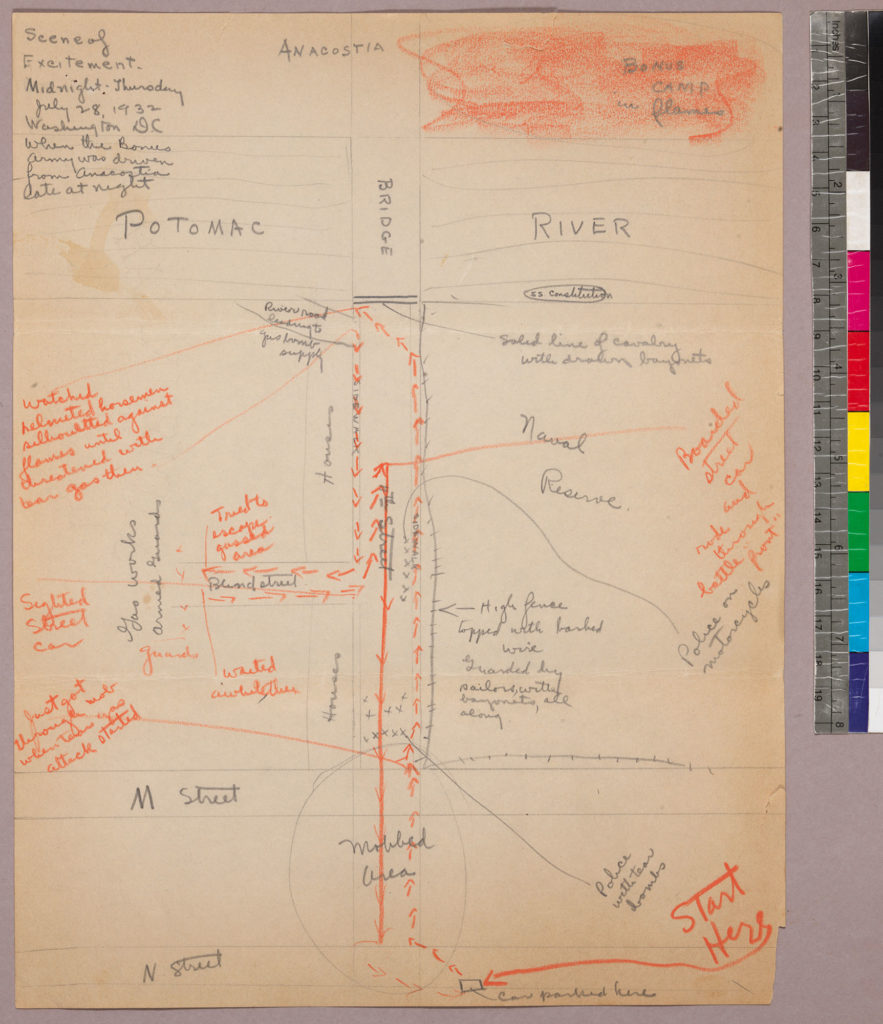

Lonore Kent’s collection offers a perspective on MacArthur’s violent overreach on the night of July 28 and the charred remains the next day. In a letter to her parents, Kent described how she used her press pass to get onto the Anacostia Bridge between Maryland and Washington, where a line of soldiers—bayonets drawn—fired tear gas at the evicted and homeless Bonus Army to keep them from crossing the bridge and entering the city. Beyond the soldiers, Kent saw the Bonus Army camp in flames.

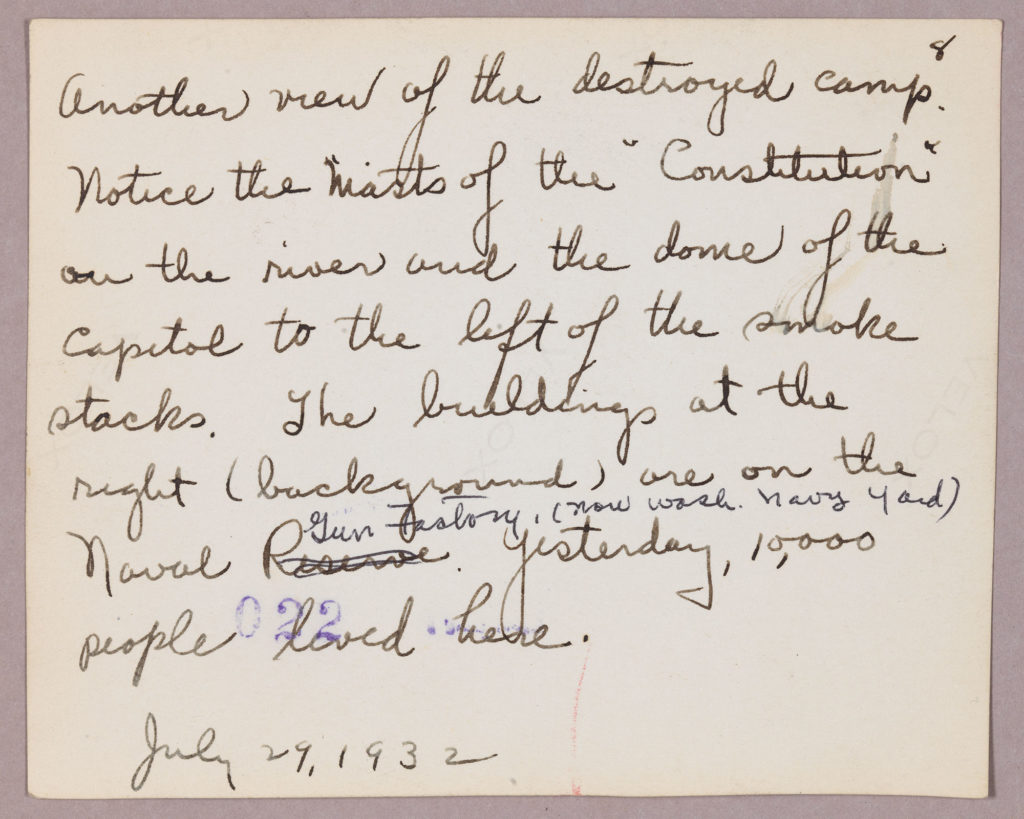

Kent drew a map of where she was that night—in relation to the soldiers, the encampment, and what she saw. (She identifies the river as the Potomac, probably short for the “Eastern Branch of the Potomac,” commonly-used for the Anacostia River.) The next day she returned to the burned-out site and documented some of the destruction. Kent reflected on the Bonus Army, noting, “Probably the granting of the bonus is unsound economically, but you can’t expect people to be impressed with such arguments when they are starving.”

Hoover’s mistreatment of the Bonus Army and general mishandling of veterans’ requests for economic assistance fatally soured the nation on his administration. The brutal ousting of the Bonus Army came to symbolize Hoover’s callous indifference to Americans’ suffering and his inability to govern amidst a national economic disaster. In the fall, Franklin Delano Roosevelt decisively defeated Hoover and implemented federal-level economic and social reforms to address the magnitude of the Great Depression. The Bonus Army, although defeated in 1932, re-formed and continued to press for an early payout, which Congress granted in 1936.

RBSC welcomes researchers to use this collection (MSN/MN 10053) and others on American history topics. For further reading see Stephen R. Ortiz, Beyond the Bonus March and GI Bill: How Veteran Politics Shaped the New Deal Era. New York: NYU Press, 2009.

A happy Memorial Day to you and yours

from all of us in Notre Dame’s Special Collections!

2016 post: Memorial Day: Stories of War by a Civil War Veteran

2017 post: “Memorial Day” poem by Joyce Kilmer

2018 post: “Decoration Day” poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

2019 post: Myths and Memorials

2020 post: Narratives about the Corby Statues—at Gettysburg and on Campus

2021 post: An Early Civil War Caricature of Jefferson Davis

2022 post: Representing Decoration Day in a 19th Century Political Magazine

Rare Books and Special Collections is closed today (May 29th) for Memorial Day and will be closed on July 4th for Independence Day. Otherwise, RBSC will be open regular hours this summer — 9:30am to 4:30pm, Monday through Friday.

During June and July the blog will shift to our summer posting schedule, with posts every other Monday rather than every week. We will resume weekly publication on August 7th.