Patrick Browne’s The Civil and Natural History of Jamaica

by Joel Gabriel Kempff, PhD Candidate, English Department, University of Notre Dame

by Joel Gabriel Kempff, PhD Candidate, English Department, University of Notre Dame

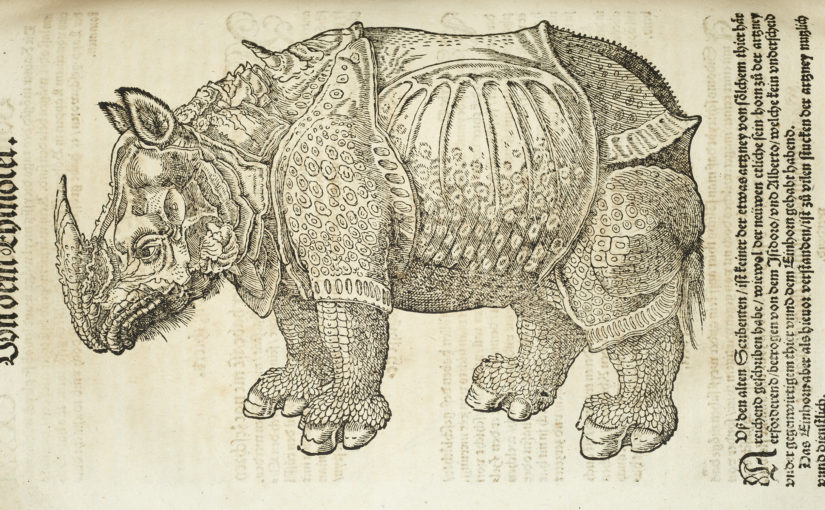

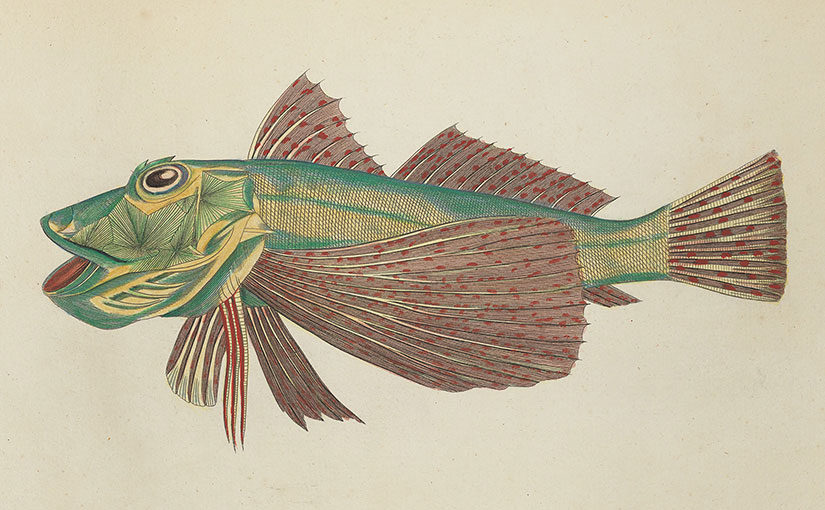

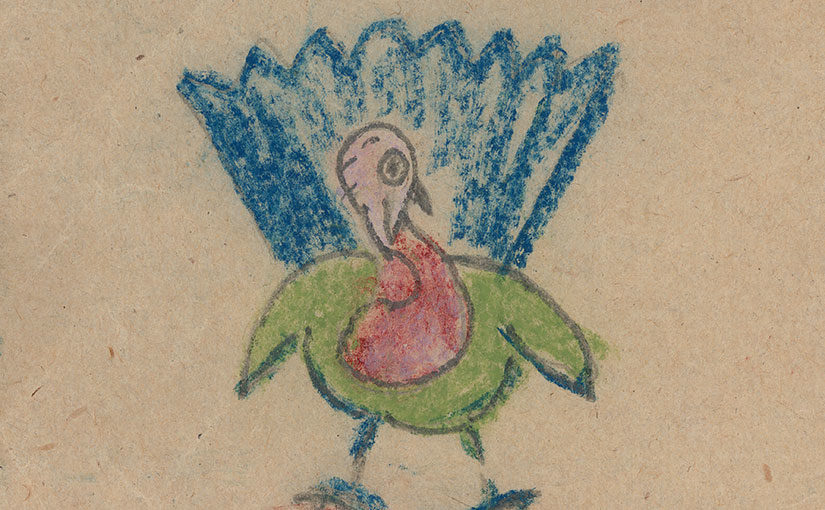

Rare Books and Special Collections is pleased to have acquired The Civil and Natural History of Jamaica. This 1789 edition of Dr. Patrick Browne’s description of the Caribbean Island, contains 49 stunning color plates, illustrated by Georg Dionysius Ehret, one of the period’s most lauded and influential botanical and entomological artists. The Civil and Natural History of Jamaica includes an account of the British colony’s governmental and economic structure at the time, a description of the soil and fossil content of the island, as well as a comprehensive account of its flora and fauna.

Patrick Browne was born in Ireland in 1720. Educated as a botanist and physician, he made the harrowing transatlantic journey six times in his life, collecting, organizing, and cataloging the natural history of not only Jamaica, but several British sugar colonies of the West Indies. In his preface to the section which catalogues the animal life of Jamaica, Browne muses eloquently on the purpose of such a book as his. Beyond its scientific value as a simple taxonomy, the creatures cataloged in his book offer important knowledge to do with a range of topics. Browne writes:

…the Naturalist endeavors to observe the peculiar forms, differences, classes and general properties of all. The nature of society we may learn from the Castor, and the rules of government, industry and friendship, from the Ant and the Bee. The little Nautilus has first taught us to sail; and the uses of the Paddle, the Lever, the Forceps, and the Saw, with a thousand other mechanical powers are daily shewn us by numbers of the insect tribe.

Browne goes on to suggest that works such as his Natural History offer a new, more respectful way of understanding so many of the world’s tiny creatures, which were before only regarded as pests that produce only “filth and putrilage.” Browne writes that is this new kind of scientific inquiry which allows humans to gain new respect, even awe, for all sorts of plants and animals. When one views such intricately drawn, to scale illustrations of a bell flower, a flying fish, or a lobster, one does indeed wonder at the complexity and beauty of such creatures and can’t help but reflect on what humans might still have to learn from the plant and animal kingdoms. At its time of publication, and even now, Browne’s work has been valued as an astonishing addition to natural philosophy and science.

Browne goes on to suggest that works such as his Natural History offer a new, more respectful way of understanding so many of the world’s tiny creatures, which were before only regarded as pests that produce only “filth and putrilage.” Browne writes that is this new kind of scientific inquiry which allows humans to gain new respect, even awe, for all sorts of plants and animals. When one views such intricately drawn, to scale illustrations of a bell flower, a flying fish, or a lobster, one does indeed wonder at the complexity and beauty of such creatures and can’t help but reflect on what humans might still have to learn from the plant and animal kingdoms. At its time of publication, and even now, Browne’s work has been valued as an astonishing addition to natural philosophy and science.

Archives of Natural History notes that Browne’s work on Jamaica “is now considered one of the most significant natural history books of the mid-eighteenth century, in some respects second only to the earliest works of Carl Linnaeus.”[1] In fact, Linnaeus himself—the father of modern taxonomy[2]—wrote from Sweden to Browne, “I never coveted any Book, I know not by what instinct, with more ardour desire than yours .. [and having] obtained it I spent day and night reading it through, I read it over but never enough … Good God how I was transported with desire of a book infinitly [sic] to be commended” and “you ough[t] to be honoured with a golden statue”. Linnaeus also wrote to the English naturalist Peter Collinson that “No author did I ever quit more instructed.”[3] Patrick Browne’s collected physical specimens now reside in the Linnaean Society Collection.

Throughout his life, and during his retirement in Ireland, Browne catalogued the flora and fauna of County Galway and of his home, County Mayo. His manuscript on Irish flora was published in the handsome Flowers of Mayo: Dr. Patrick Browne’s Fasciculus Plantarum Hibernicae 1788, edited and with substantial commentaries by Charles Nelson of the Irish National Botanic Gardens. This book, with color plates by Wendy Walsh, may also be viewed in the Hesburgh Special Collections.

Dr. Browne was known as a gentle and generous man by his colleagues. He married an Antiguan woman who lived with him in Ireland until his death on August 29th, 1790.

[1] E. C. Nelson, ‘Patrick Browne’s The civil and natural history of Jamaica (1756, 1789)’, Archives of Natural History, vol. 24 (1997), p.327–36.

[2] Calisher, CH (2007). “Taxonomy: what’s in a name? Doesn’t a rose by any other name smell as sweet?”. Croatian Medical Journal. 48 (2): 268–270.

[3] Transactions of the Linnaean Society, iv (1798), 31–4.