by Aedín Ní Bhróithe Clements, Irish Studies Librarian

At Hesburgh Libraries, along with the Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies, we look forward to participating in the worldwide celebration on February 2nd of the one hundredth anniversary of James Joyce’s Ulysses.

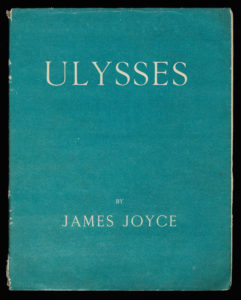

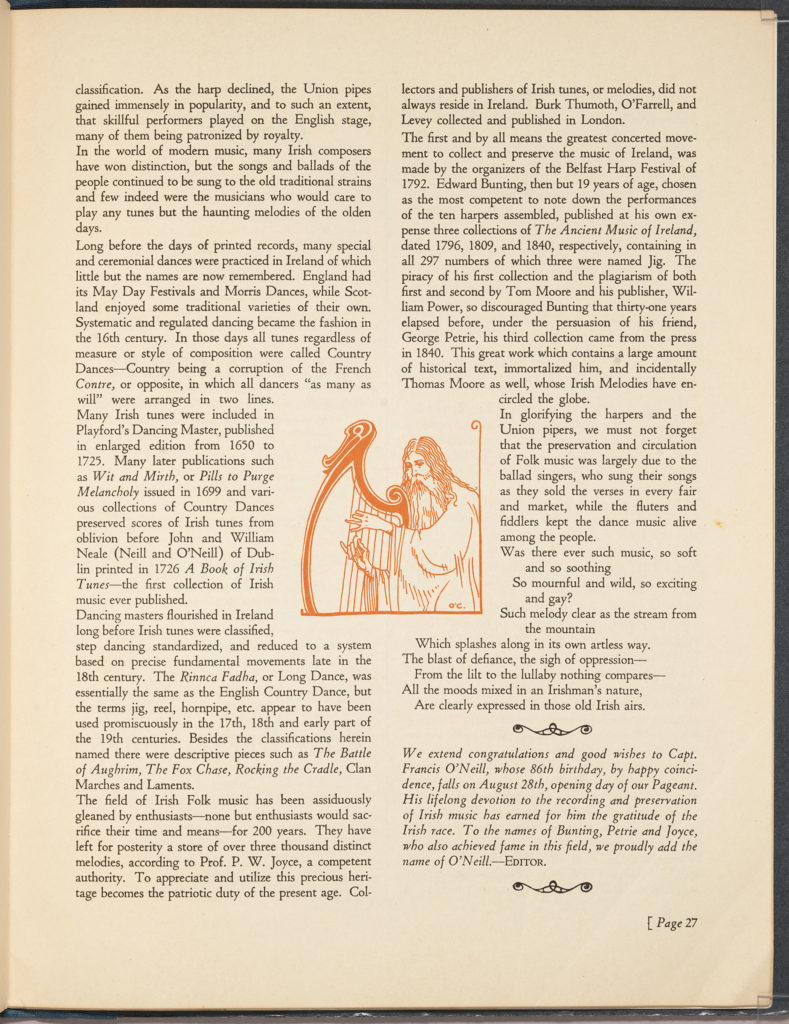

The very first copies of the first edition of Ulysses were received from the printer on Joyce’s fortieth birthday, February 2nd, 1922. Sylvia Beach, the publisher, delivered a copy to James Joyce on that day.

Of the thousand copies printed in that first edition, almost one hundred are currently in U.S. libraries. Our copy will be on display in our exhibition room throughout the semester.

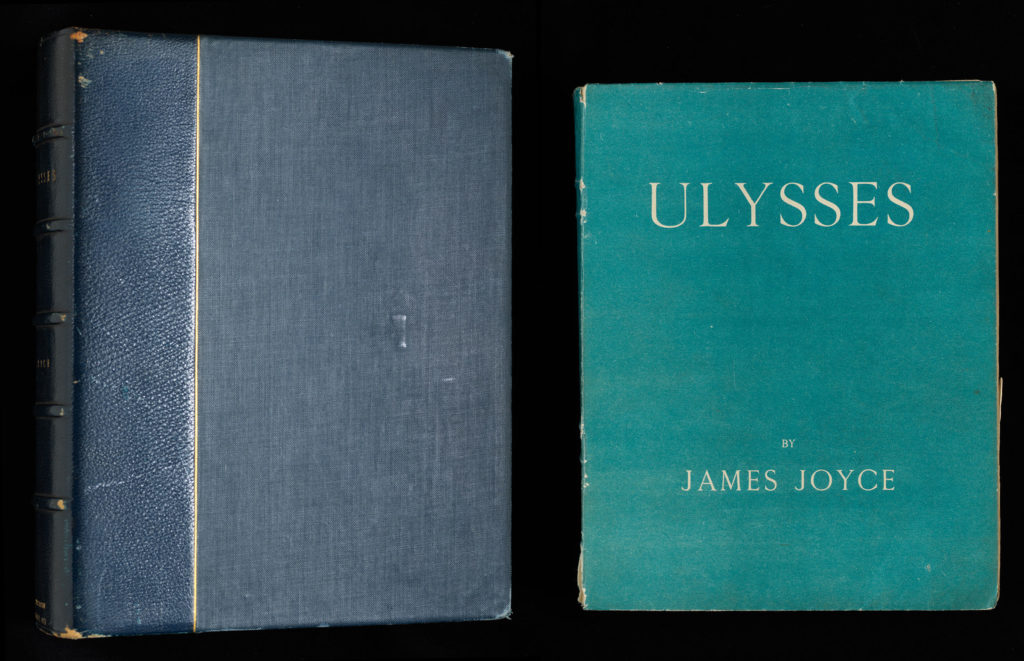

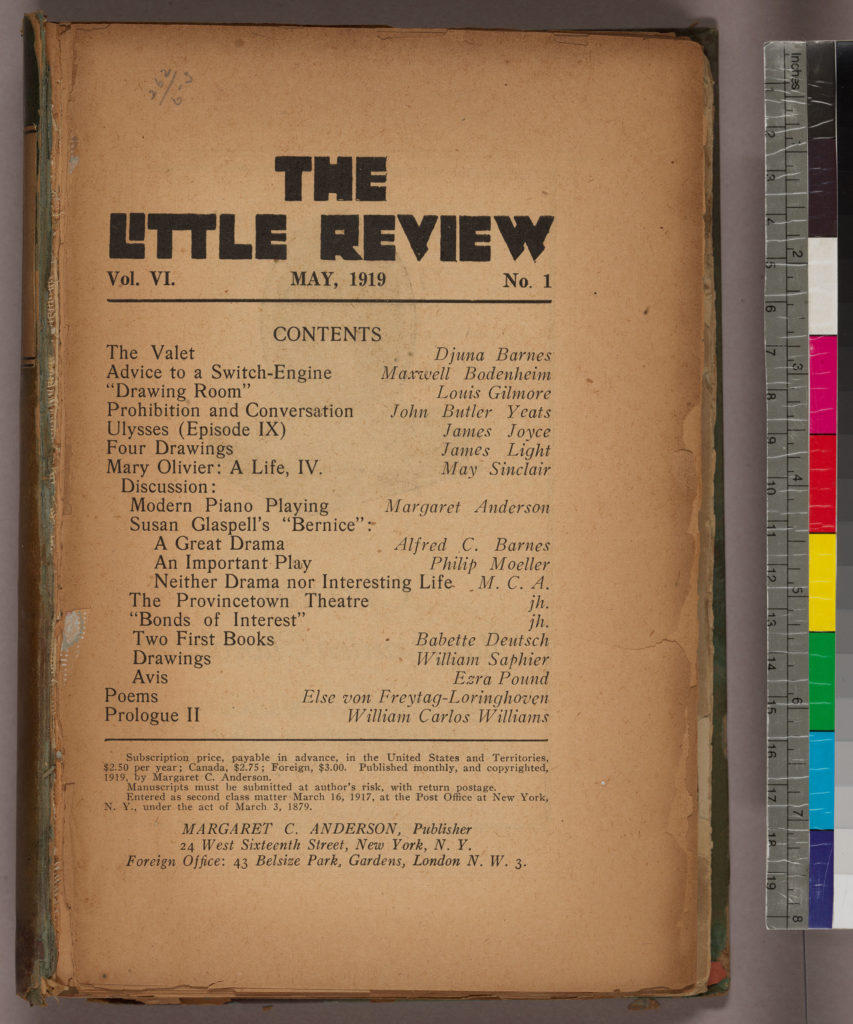

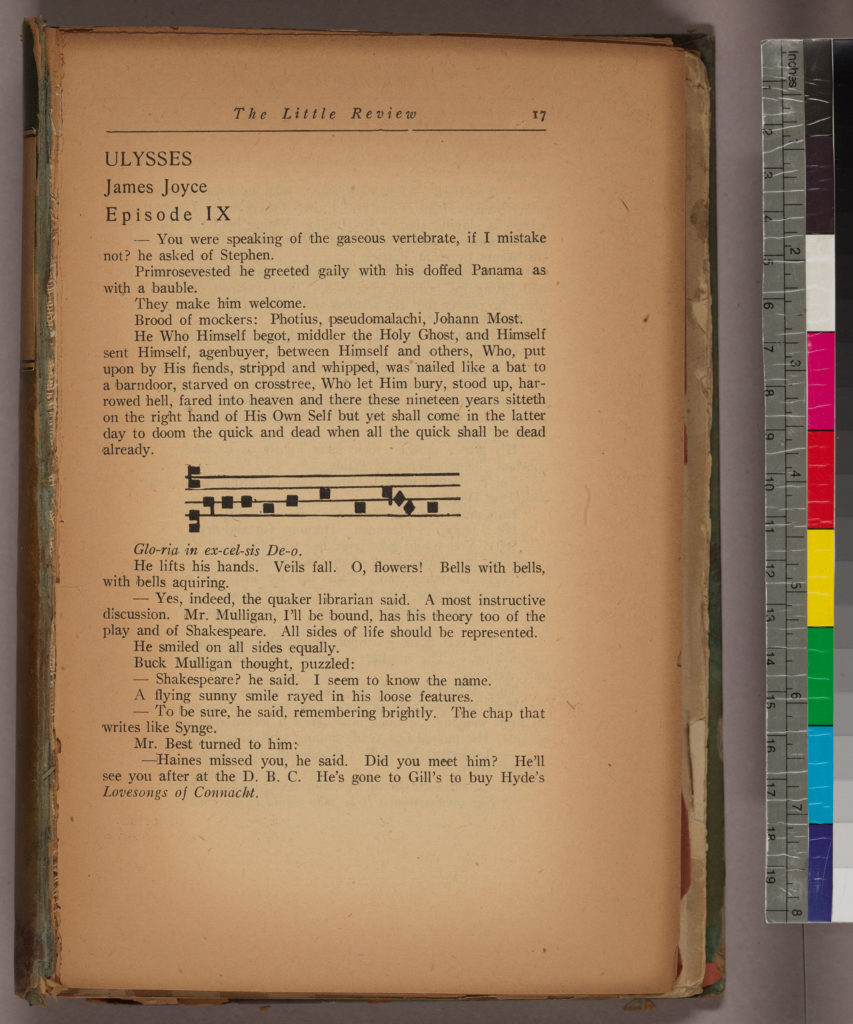

Parts of Joyce’s novel had earlier been published serially in America in The Little Review, a magazine edited by Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap. This came to the attention of the Society for the Suppression of Vice, and eventually the magazine had to cease publication of the novel and it was banned by the United States Post Office.

Joyce subsequently had difficulty finding a publisher, and Sylvia Beach, owner of Paris bookshop and lending library Shakespeare and Company, agreed to publish the book. Every detail along the way, from finding typists who would agree to type the text through distributing (sometimes smuggling) the book to readers, forms an interesting story. Much of the story is recounted in Noel Riley Fitch’s book, Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation (1983).

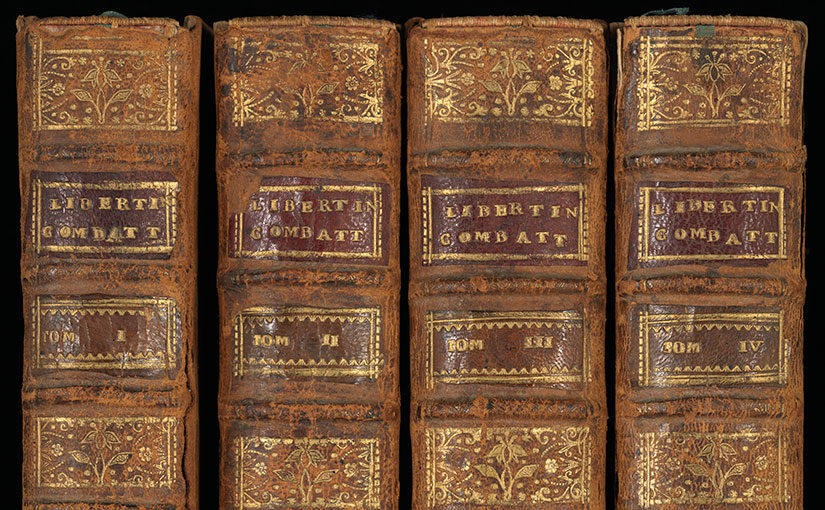

Another great champion of Joyce’s writing was publisher Harriet Weaver, whose Egoist Press in England published a number of his works. Her edition of Ulysses was also published in 1922 and our copy is on display.

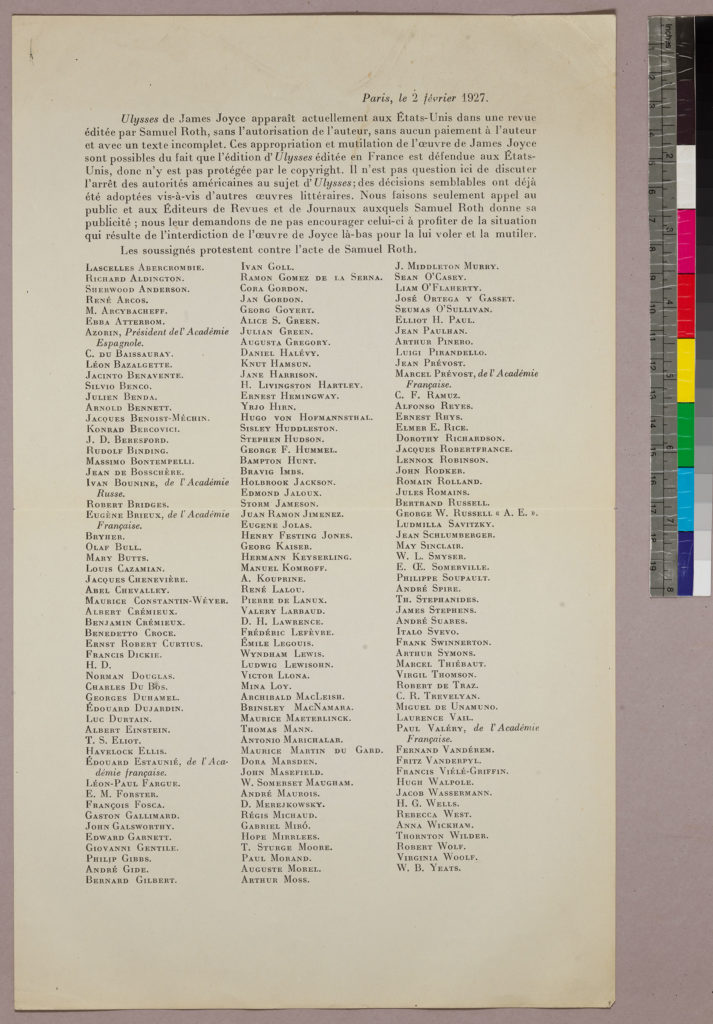

Also in the display case is a magazine in which unauthorized episodes were published, alongside a printed copy of the protest, signed by 167 artists and writers, against this piracy.

In a separate case, we will exhibit a print by the late Irish artist David Lilburn – Eccles Street, from In Medias Res: The Ulysses Maps: A Dublin Odyssey. This print will be available for viewing through the month of February.

The Celebration

On Joyce’s 140th birthday, we will host a special event in the Hesburgh Library, with the Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies.

Professor Barry McCrea will speak on ‘Joyce, Proust, Paris, 1922’, and the launch of the ‘100 Years of James Joyce’s Ulysses‘ exhibit will be complemented by a one-afternoon temporary display.

Further information on this event is available here: https://irishstudies.nd.edu/events/2022/02/02/celebration-100-years-of-james-joyces-ulysses/