We join with The Library of Congress, National Archives and Records Administration, National Endowment for the Humanities, National Gallery of Art, National Park Service, Smithsonian Institution and United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in paying tribute to the generations of African Americans who struggled with adversity to achieve full citizenship in American society.

Remembering the Harrisburg Trojans, Champion African American Football Team

by Greg Bond, Sports Archivist and Curator, Joyce Sports Research Collection

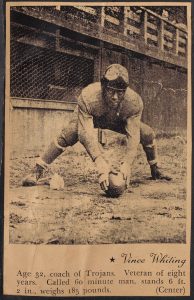

In recognition of Black History Month and in conjunction with the upcoming Super Bowl, Rare Books and Special Collections is pleased to highlight the recent acquisition of a unique vintage homemade fan poster about the Harrisburg Trojans.

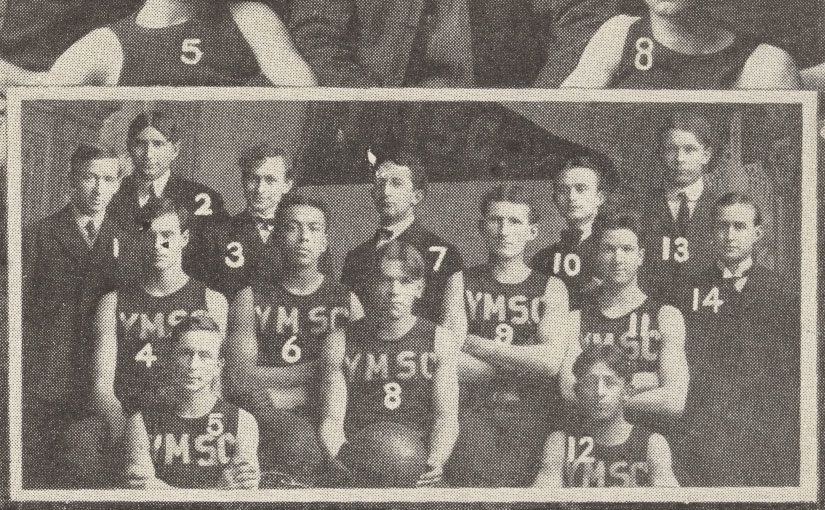

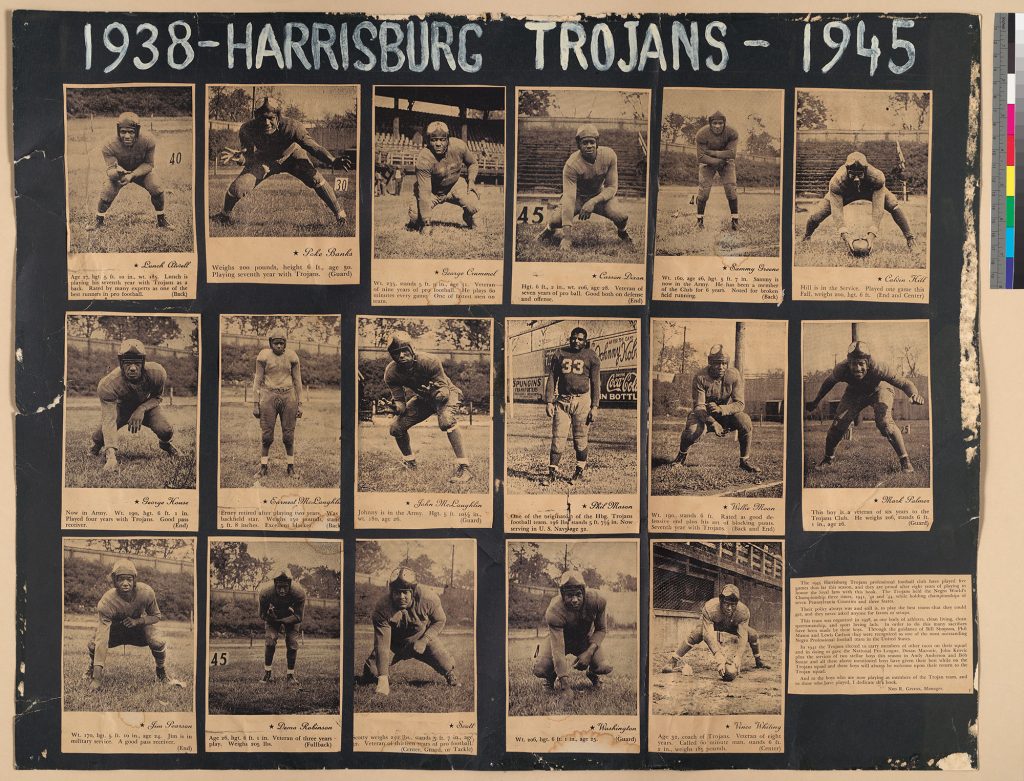

Although mostly forgotten today, the Trojans were one of the best African American football teams in the World War Two-era and the winner of the unofficial “World Negro Football Championship” in 1941. This 28-inch by 22-inch poster made by an unknown fan in about 1945 celebrates the accomplishments of the Trojans and provides a rare insight into fan culture around African American sports teams during the era of segregation.

Founded in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in 1938, the Trojans were composed mainly of African American athletes who had played high school football in the region, and they quickly developed a reputation as a talented team. The Trojans attracted considerable press coverage and routinely drew big crowds for the high quality of their play against both white and African American semi-pro, amateur, and professional teams.

The Trojans regularly competed at the highest levels of African American football. On Sunday, November 2, 1941, for example, the New York Brown Bombers, one of the best and most well-known African American teams in the country, visited Harrisburg and played the Trojans in a game billed as the “World Negro Football Championship.”

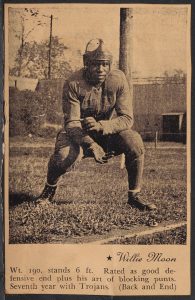

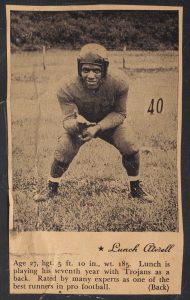

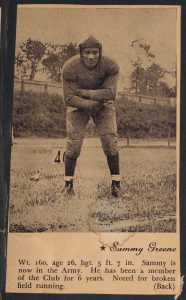

In a thrilling and hard-fought game, the Trojans upset the favored Brown Bombers 12 to 7 to claim the title of best Black football team in the country. Willie Moon was the star for Harrisburg, accounting for all of the Trojans’ points. In the second quarter, Moon blocked a Brown Bombers’ punt and recovered the ball in the end zone for a touchdown. Trailing 7-6, late in the fourth quarter, Harrisburg’s Lunch Atwell recovered a Brown Bombers fumble on a punt return to set up more heroics by Moon. With one minute left in the game, Moon made a leaping catch in the end zone of a 22-yard pass by Sammy Greene for the game-winning touchdown.

The local Harrisburg Telegraph newspaper (November 3, 1941, page 12) described the action:

When Willie Moon rose up in back of the goal line to snare a long forward pass for a touchdown, in the waning minutes of play, the Harrisburg Trojans football team yesterday beat the highly-touted New York Brown Bombers, 12 to 7, and cinched the World’s Negro football championship.

Moon’s spectacular leap into the air for the pass thrown diagonally across the field by Sammy Greene, was the climax of one of the most thrilling grid battles seen here for a long while, and it was also a signal for hundreds of the more than 4000 persons in the stands to rush onto the playing field at Island Park to congratulate the ultimate victors.

In 1942 and 1943, the strong Washington Lions team visited Harrisburg to challenge the Trojans for the “Negro Football Championship.” In 1942, the two teams played to a 7-7 tie, and, the following year, the Lions beat Harrisburg 8-0 to earn the title.

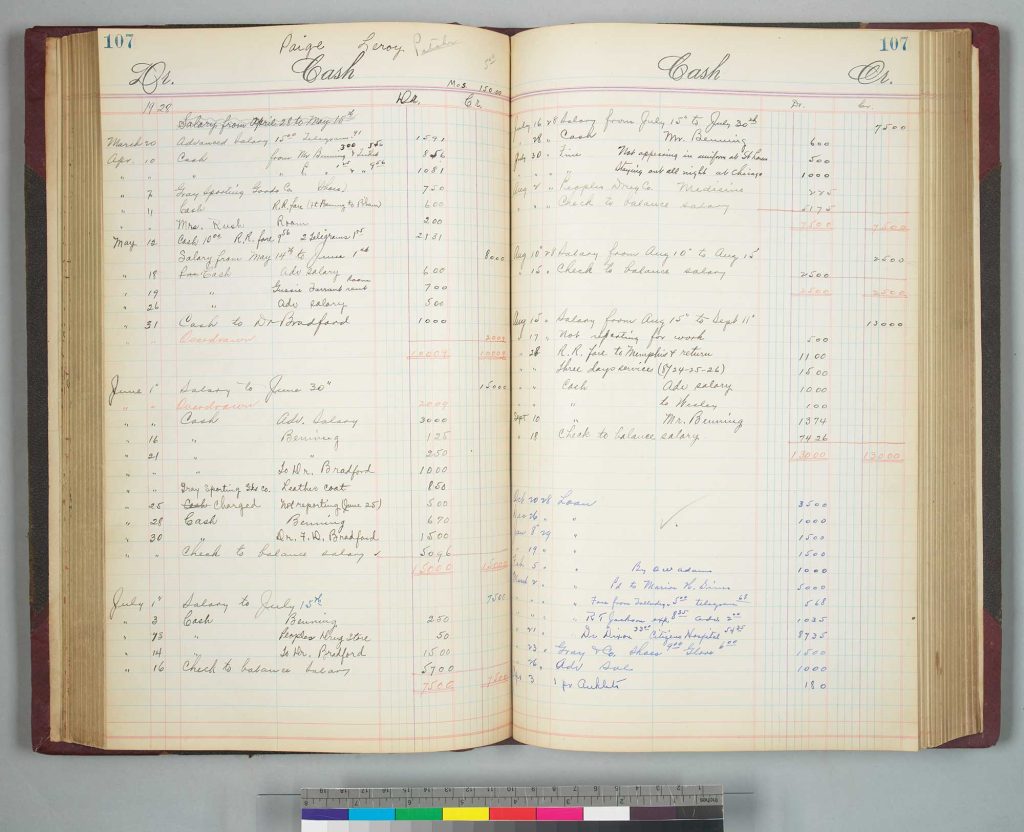

The Trojans’ financial and administrative affairs were handled in these years by business manager Ned R. Givens and promoter William E. “Bud” Marshall. The Trojans continued playing each fall through about the 1950 season.

Unusually, although the players on the Trojans were predominantly African American, the team added white players to its roster for both the 1942 and 1945 seasons. In 1942, the Trojans fielded white players Dusan “Duke” Maronic—who would go on to play in the NFL for the Philadelphia Eagles from 1944 through 1950—and John Krovic. In 1945, the team included white players Andy Anderson and Bob Sostar.

Years after, Duke Maronic recalled his time with the Trojans: “Later, I played for the Harrisburg Trojans. They were an all-Negro team. I was the only white guy on the Team. I never gave much thought to it. Neither did the black guys, but once in a while one of the opponents would make a remark.”

Besides old clippings from the 1930s and 1940s in central Pennsylvania newspapers or in the African American press, however, there is little available information about the Harrisburg Trojans. Fortunately for researchers, the anonymous creator of this remarkable fan poster has preserved an exceedingly rare source about the Trojans.

On a piece of black cardboard underneath a heading that reads “1938-Harrisburg Trojans-1945,” the unknown fan has pasted clippings from a promotional pamphlet written and published by business manager Givens. Except for these extracts, there are apparently no other known extant copies of Givens’s pamphlet. It is also unknown if the publication originally included more material than is seen here.

In a clipping from the poster about the history of the team, Givens wrote that the Trojans’

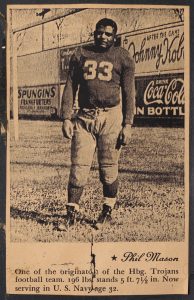

“… policy always was and still is, to play the best teams that they could get, and they never asked anyone for favors or setups. This team was organized in 1938, as one body of athletes, clean living, clean sportsmanship, and sport loving lads. In order to do this, many sacrifices have been made by these boys. Through the guidance of Bill Simpson, Phil Mason and Lewis Carlton they were recognized as one of the most outstanding Negro Professional football teams in the United States.”

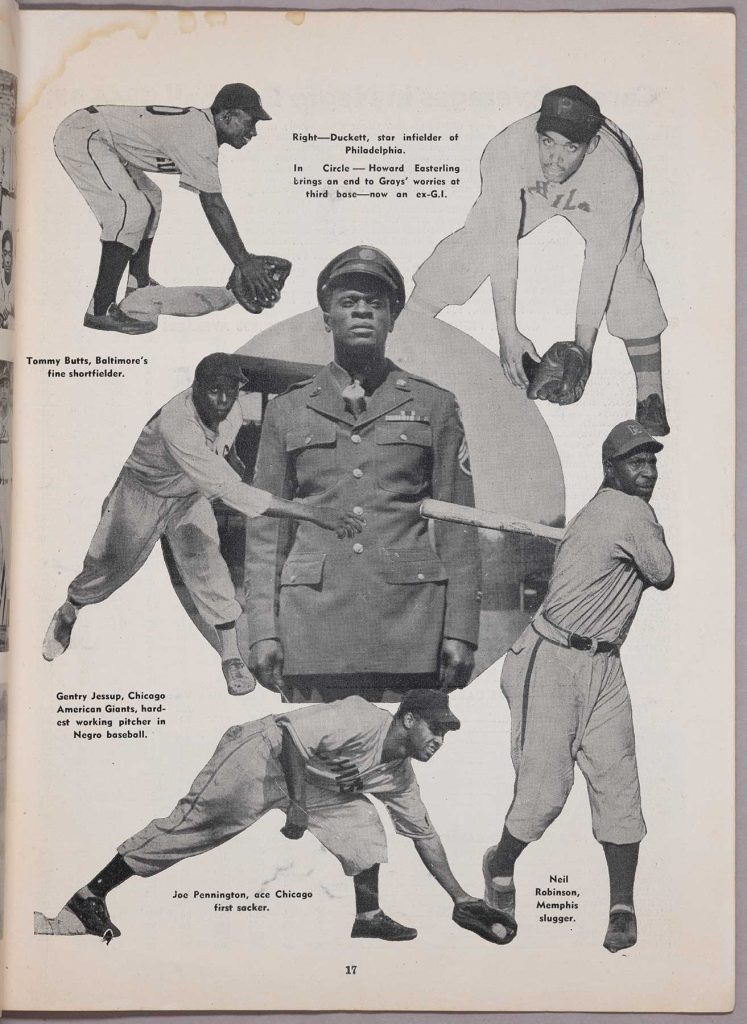

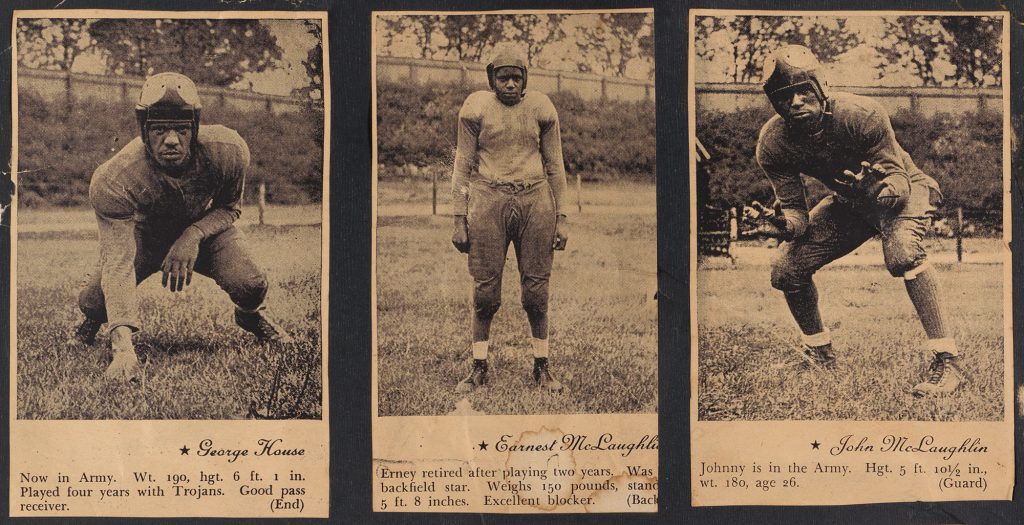

The poster features rare images and short bios from Givens’s pamphlet about 17 different men who played for the Trojans. The pictures capture talented and serious African American football players ready for action. And the remarkable piece of fan art provides a glimpse into the significance of African American sports teams during the mid-twentieth century and the way in which at least one fan related to the Trojans.

In his pamphlet, Givens concluded his brief historical summary of the team by writing: “And to the boys who are now playing as members of the Trojan team, and to those who have played, I dedicate this book.”

Today, we remember and celebrate the accomplishments of the Harrisburg Trojans and dedicate this post to their legacy.

Previous Black History Month Blog Posts:

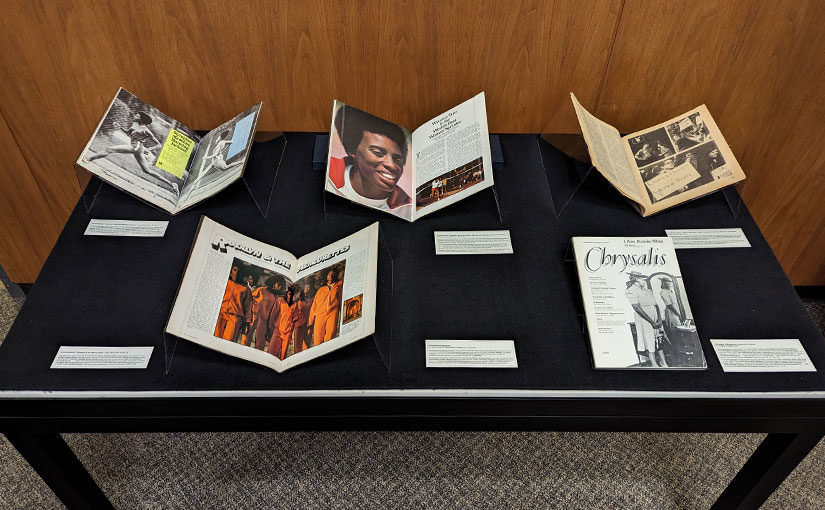

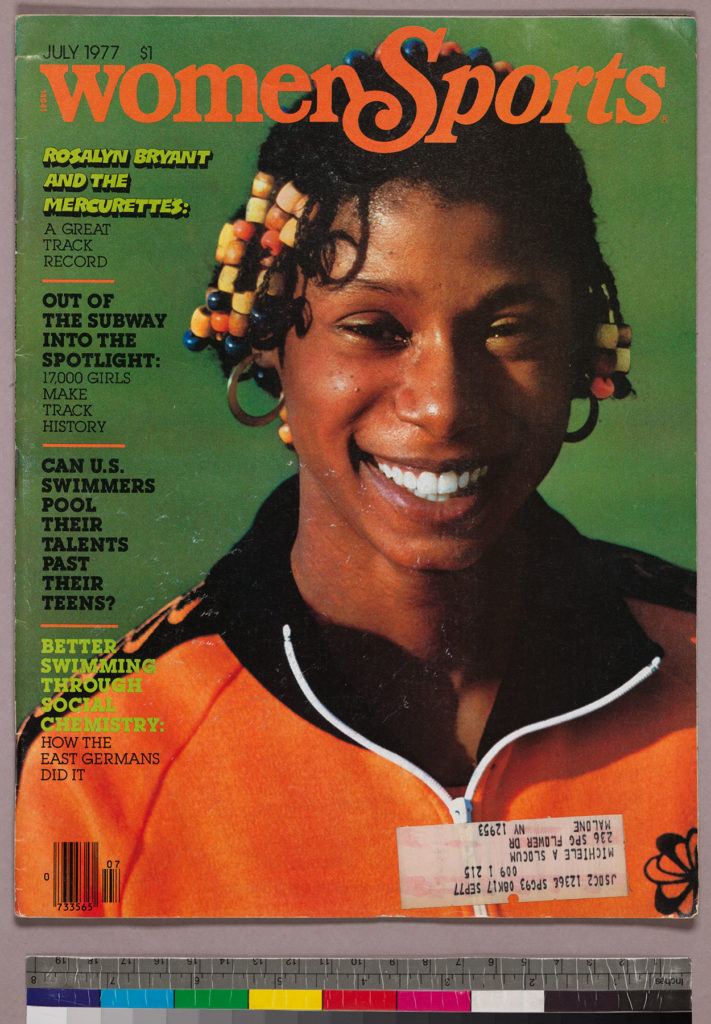

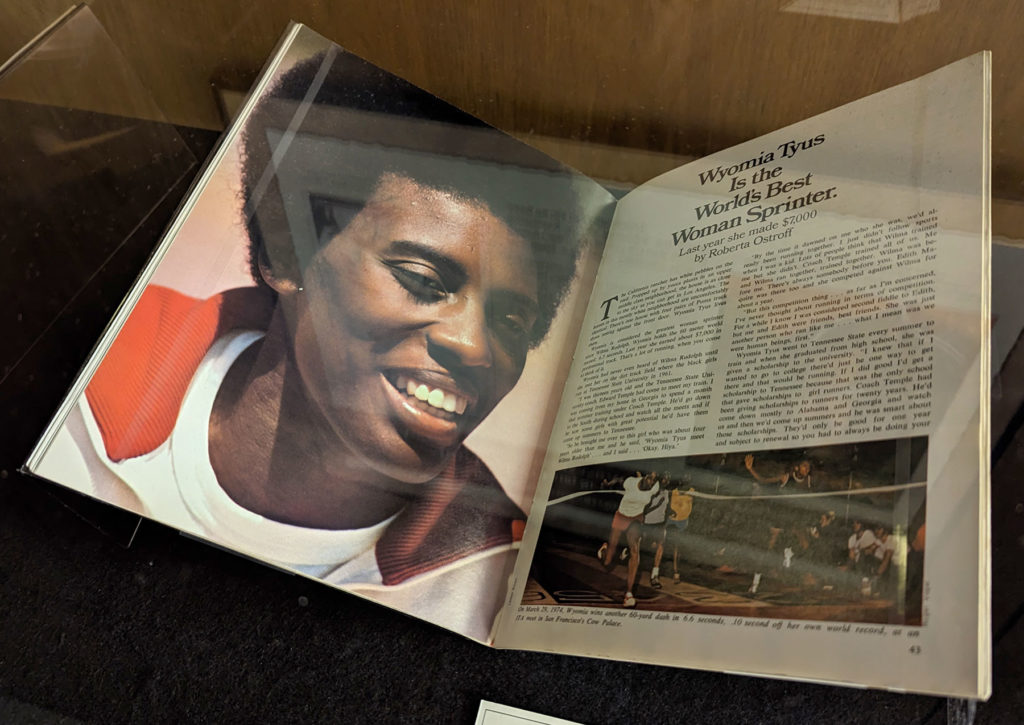

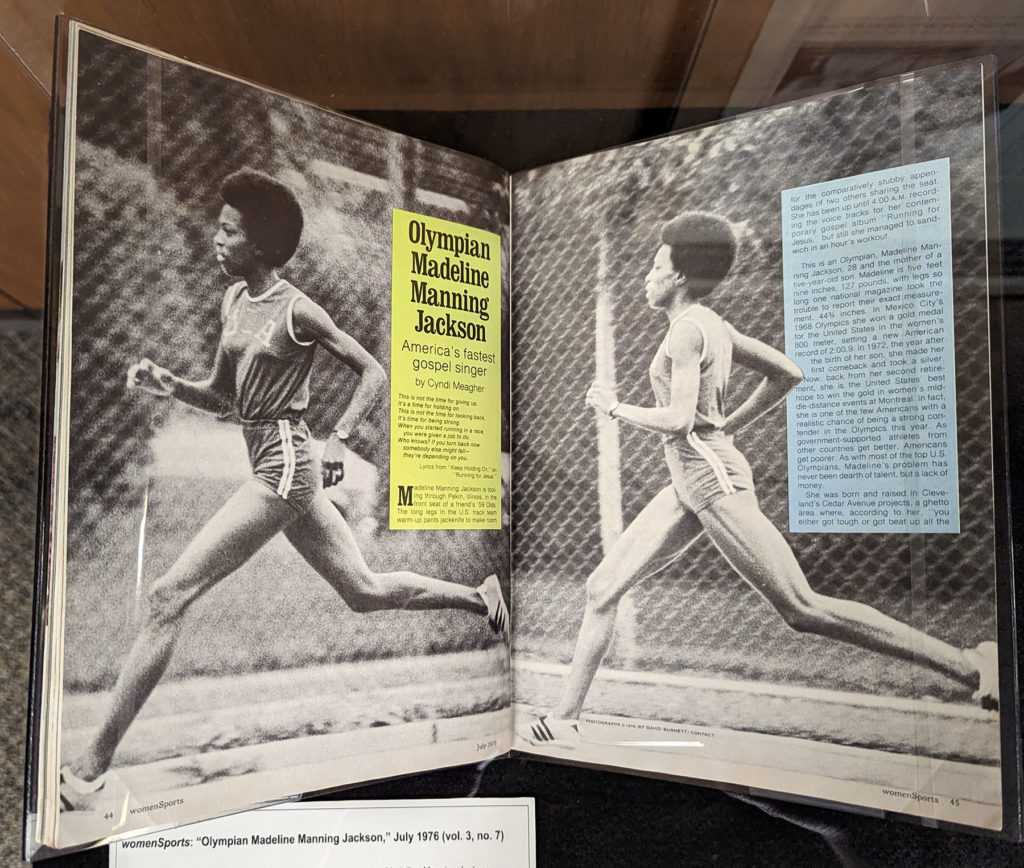

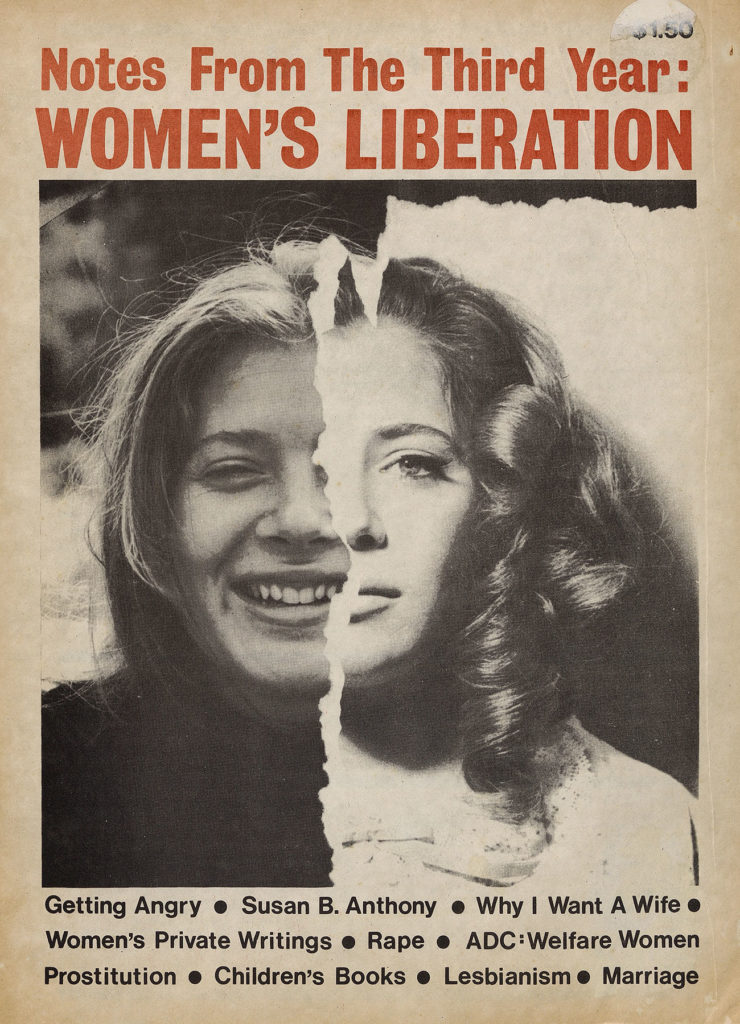

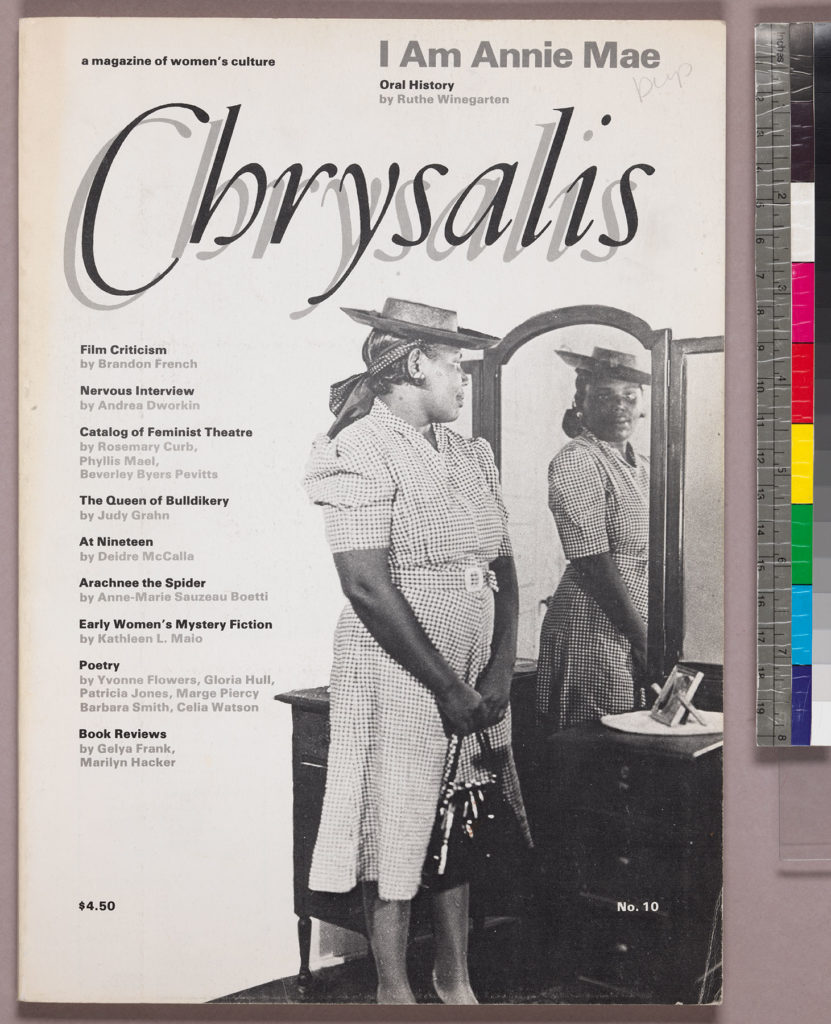

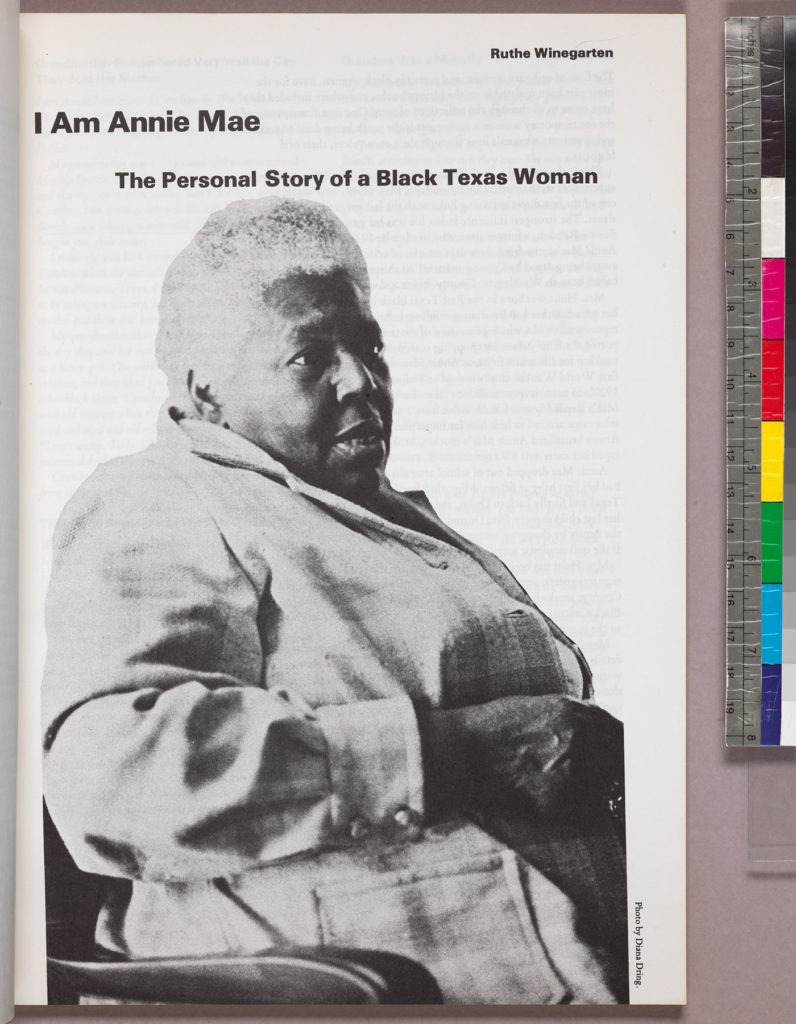

2023: African American Women Activists and Athletes in 1970s Feminist Magazines

2021: Paul Laurence Dunbar’s New Literary Tradition Packaged to Sell