by Aedín Ní Bhróithe Clements, Irish Studies Librarian

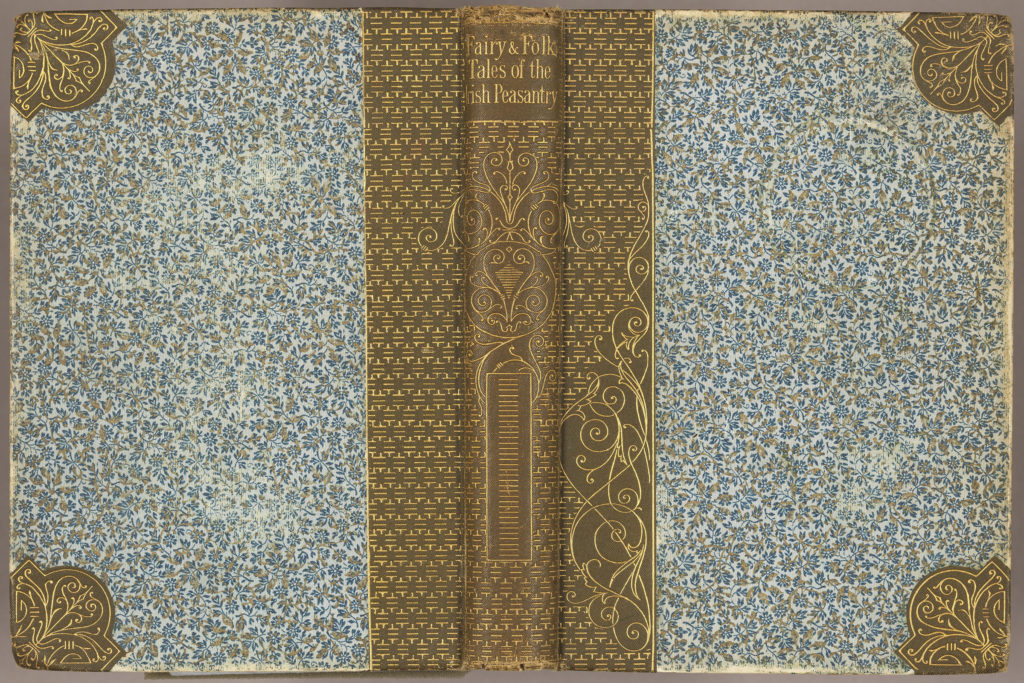

Most of the books in our W. B. Yeats collection sit neatly on the literature shelves — in fact, the majority are in the ‘rare medium’ shelves as our special collections are organized in various size ranges. Exceptions, however, with variant editions found in the ‘rare small’ sections of folklore and children’s literature section, are Yeats’s Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry and his Irish Fairy Tales.

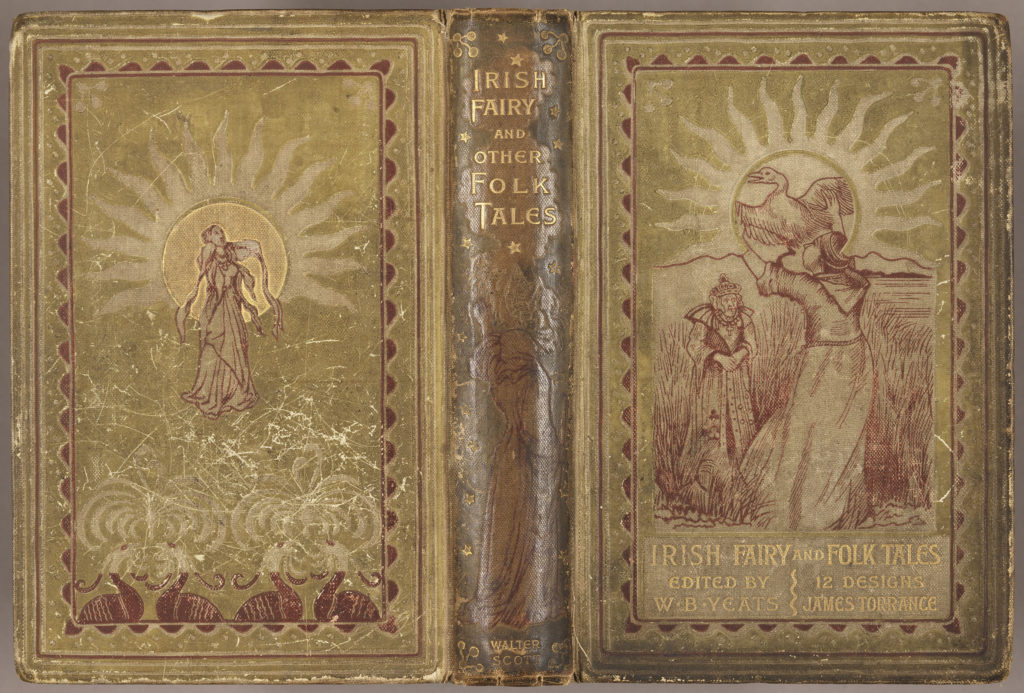

London: W. Scott, undated. Rare Books Small GR 153.5 .F34 1880z

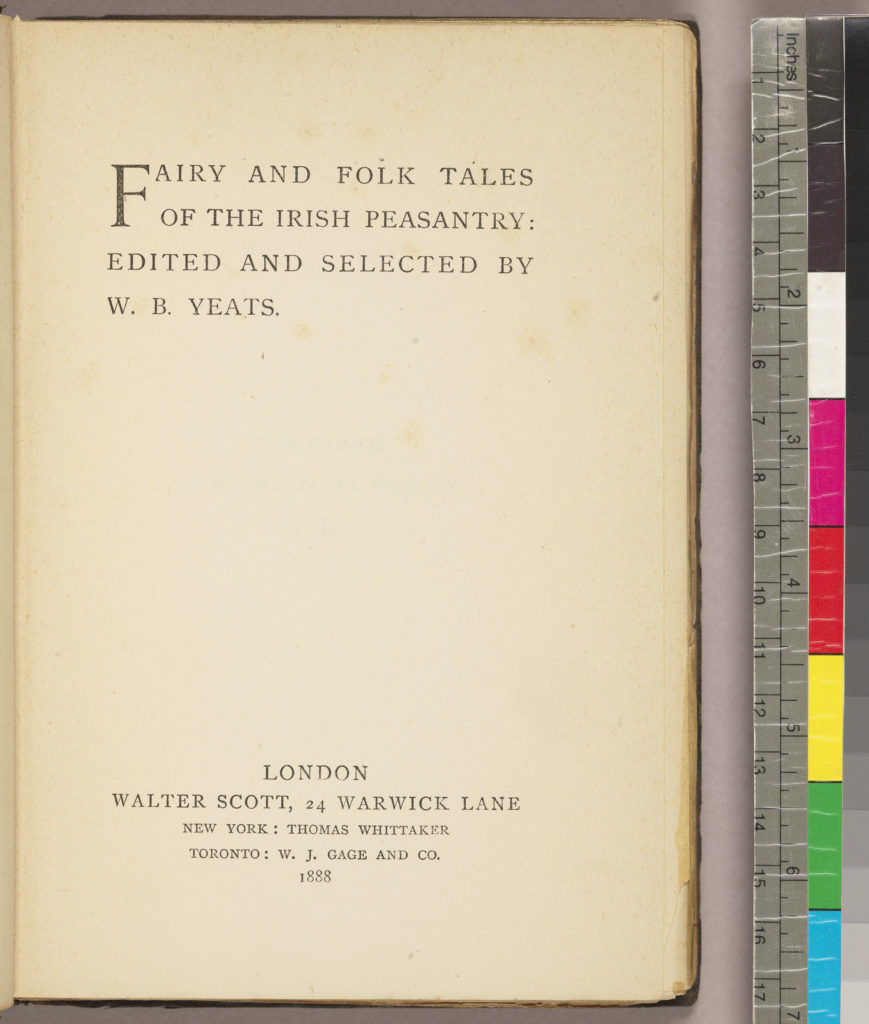

Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry was one of Yeats’s earliest published books. At the time of this work, Yeats had been publishing in periodicals for about four years, mostly in the Dublin University Review. He had published one book of poetry, Mosada, now exceedingly rare, in 1886, and was working on having his next collection published — The Wanderings of Oisin and Other Poems. His published poetry and other writing of the time demonstrate a great interest in folklore, and in stories of fairies, ghosts and other phenomena of folklore. His reading on the subject was complemented by encounters with the people of County Sligo, where he spent much of his time.

To find Yeats discussing this publication, we can consult John Kelly’s great compilation, The Collected Letters of W. B. Yeats, which, fortunately, we have in digital form and so can easily search the letters for references to folklore and fairies. Thus we learn that Yeats was invited by his friend Ernest Rhys to produce a book of folklore for the Camelot Series of prose writing, to be published by Walter Scott.

Yeats writes to his friend Katharine Tynan in February, 1888:

I am trying to get some sort of regular work to do however, it is neccessary, and better any way than writing articles about things that do not interest one — are not in ones line of developement — not that I am not very glad to do the Folklore book or any thing that comes to my hand.

Kelly, 47-48

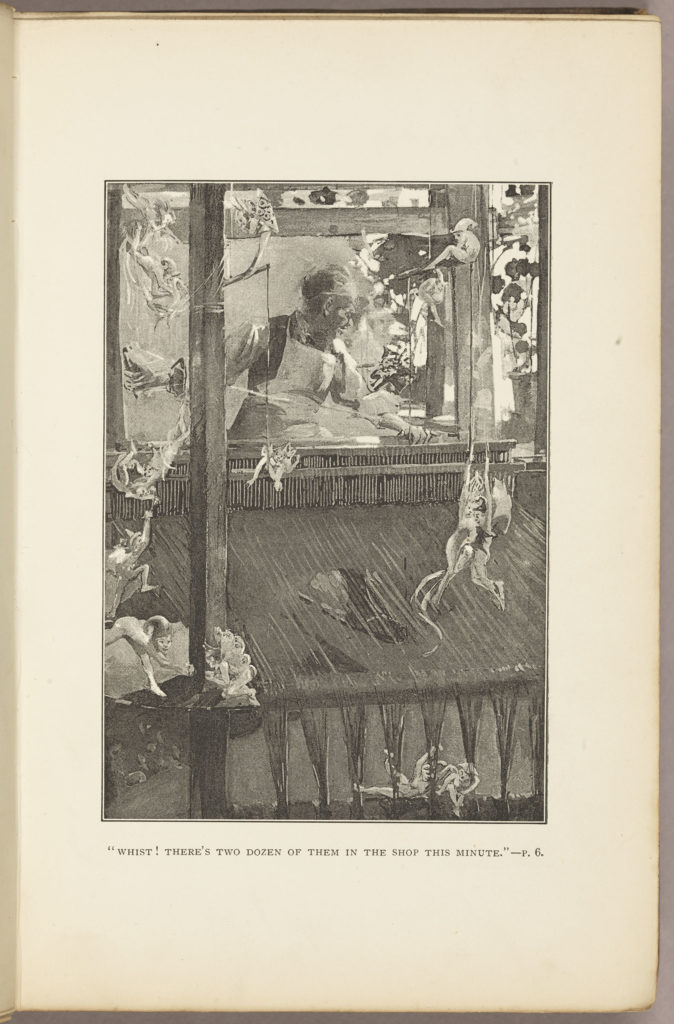

Irish fairy and folk tales / selected and ed. with introduction, by W.B. Yeats. Twelve illustrations by James Torrance. London: W. Scott, [1893?]

In the letters we also find Yeats consulting with Douglas Hyde on the book.

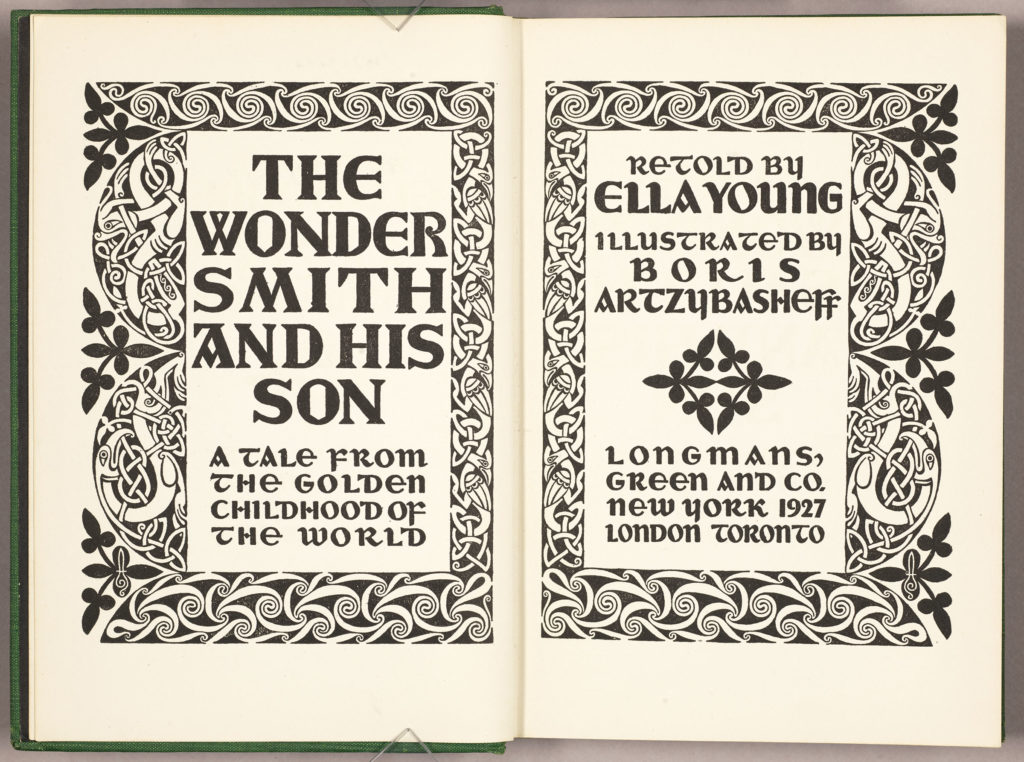

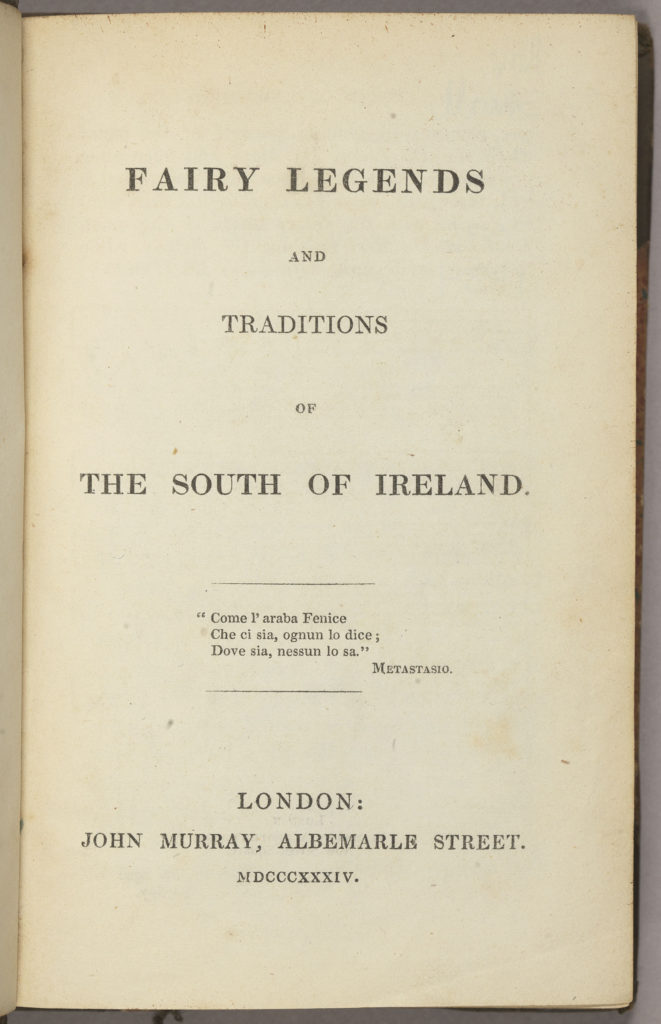

Yeats’s selection includes stories written by his friends, Douglas Hyde and Katharine Tynan and other contemporaries, and also by earlier writers, among them Crofton Croker, whose early nineteenth century collections of folklore were very popular.

In the introduction to the 1888 book, Yeats discusses the context for storytelling in the community, and he argues the merits of the folklore collectors included in his book, saying that “they have made their work literature rather than science” and that they have “caught the very voice of the people” (xiv).

Most of Yeats’s early encounters with the rural Irish were in Sligo, where his mother’s family lived, and here he introduces a story-teller of his acquaintance, Paddy Flynn, “a little, bright-eyed, old man, living in a leaky one-roomed cottage” who tells stories of Columkill (Colmcille) and who has told Yeats matter-of-factly of his sighting of the Banshee.

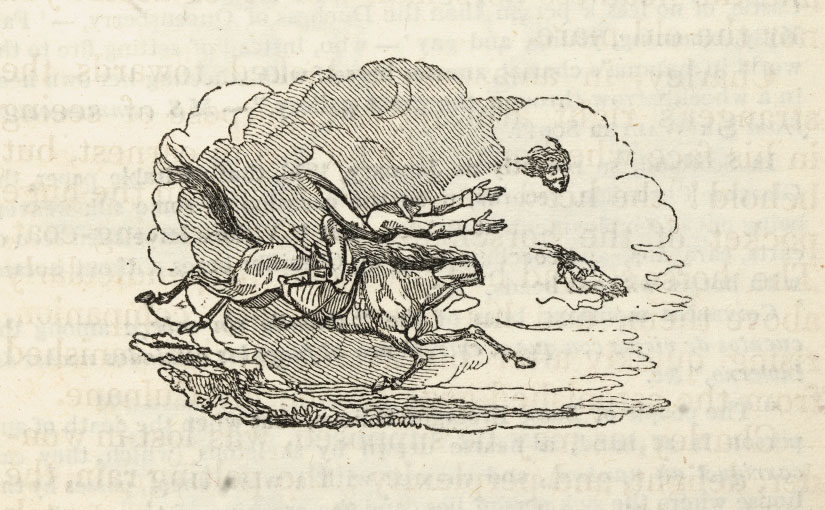

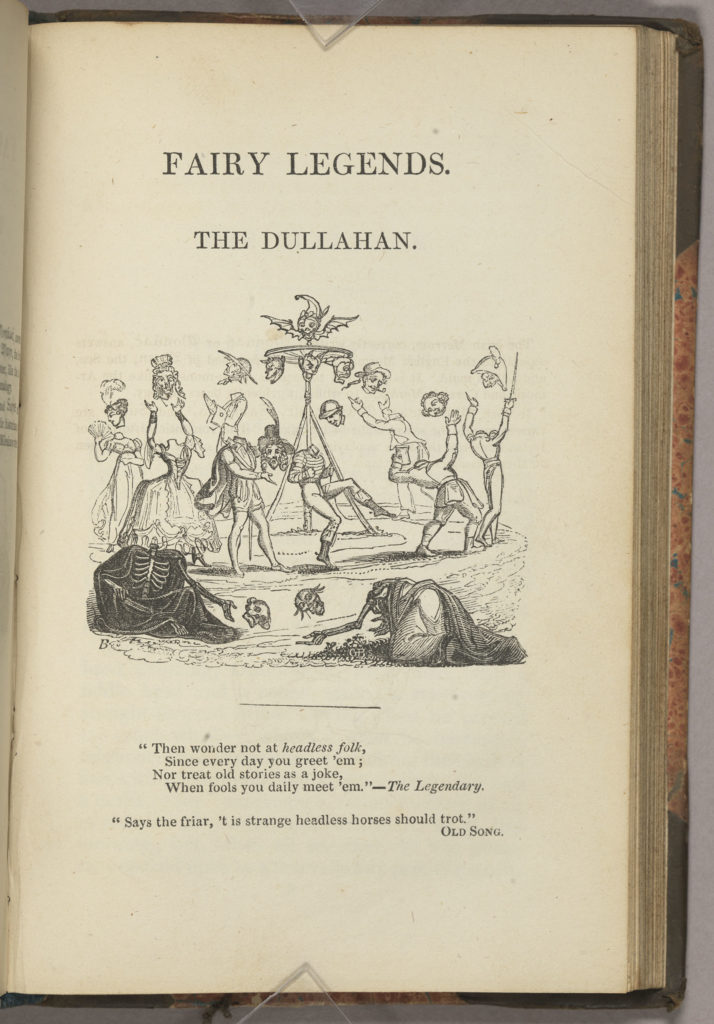

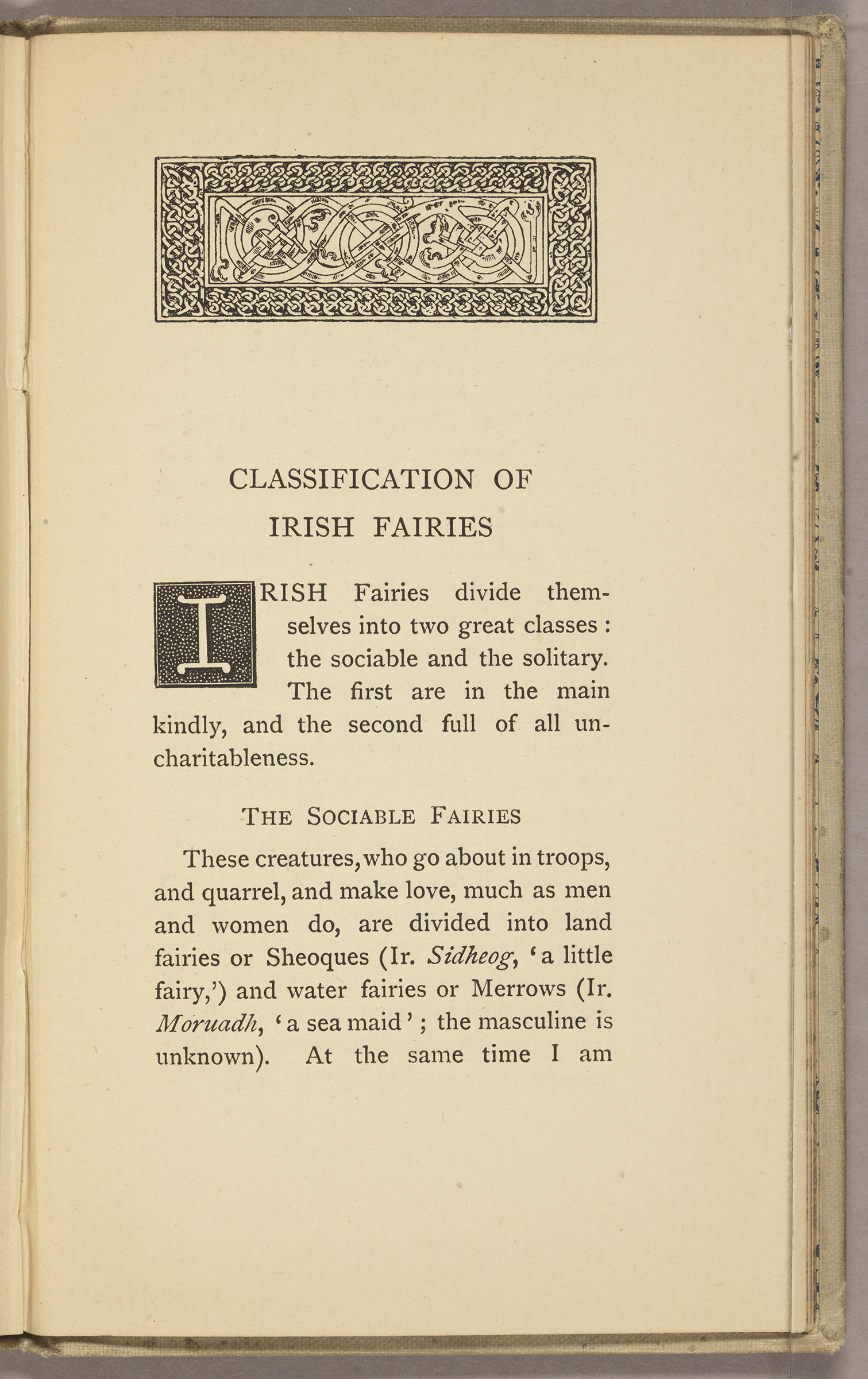

The chapters demonstrate the editor’s interest in the various supernatural or magical creatures and phenomena found in Irish folklore. The sections on fairies are divided into ‘The Trooping Fairies’ and ‘The Solitary Fairies’. In the first are stories of Changelings, and of the Merrow (a sea-being), while the Solitary Fairies include the Leprechaun and his variants, and also the Pooka and the Banshee.

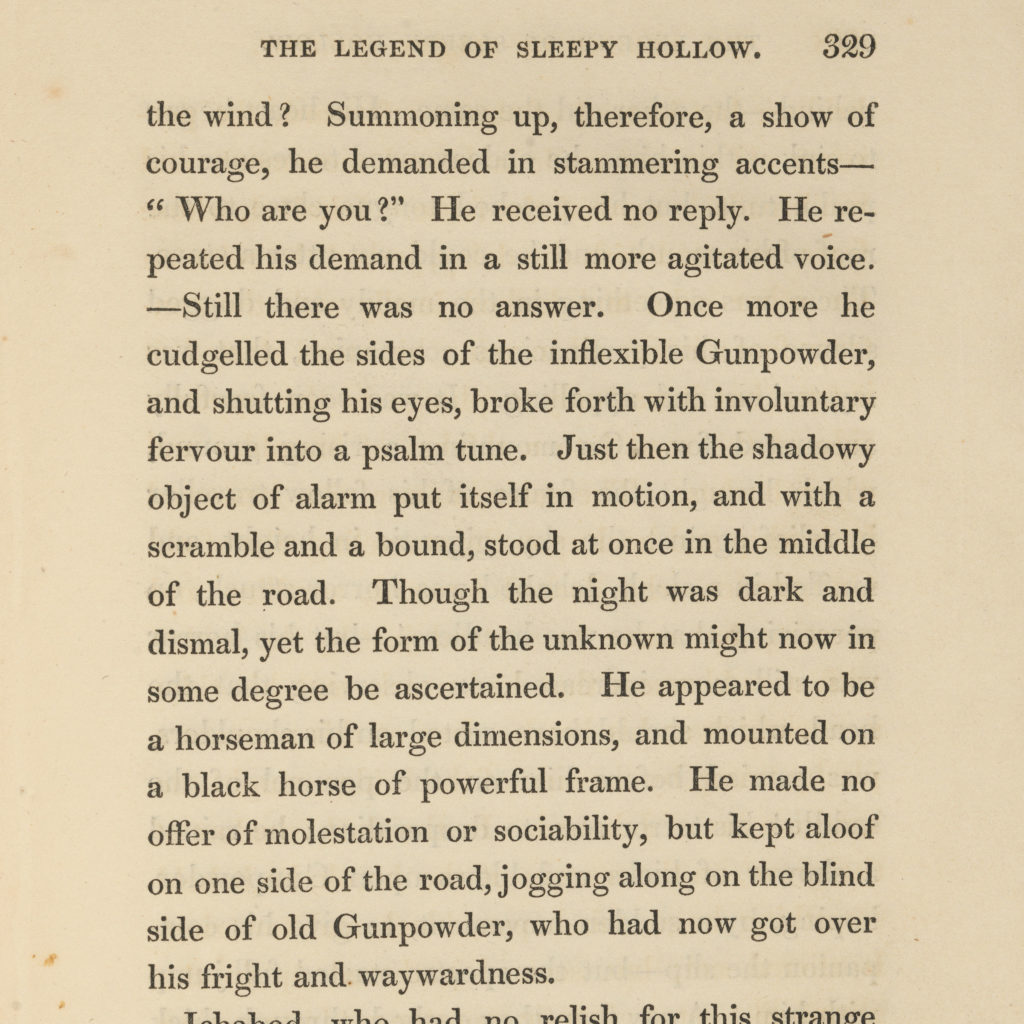

The stories collected from folklore are interspersed with verse, including, for example William Allingham’s ‘The Fairies’, with which the collection begins. In the section on the Changeling, we find an example of one of Yeats’s own compositions, his well-known poem ‘The Stolen Child’, with an early version of the refrain uttered by the fairies to entice the child to leave and join them:

Come away, O, human child!

W. B. Yeats, ‘The Stolen Child’, in Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry (1888), p. 59.

To the woods and waters wild,

With a fairy hand in hand,

For the world’s more full of weeping than

you can understand.

The rest of the chapters cover characters ranging from ghosts to priests, and there is also a chapter called ‘Tyeer-Na-N-Og’ (Tír na nÓg — the land of youth).

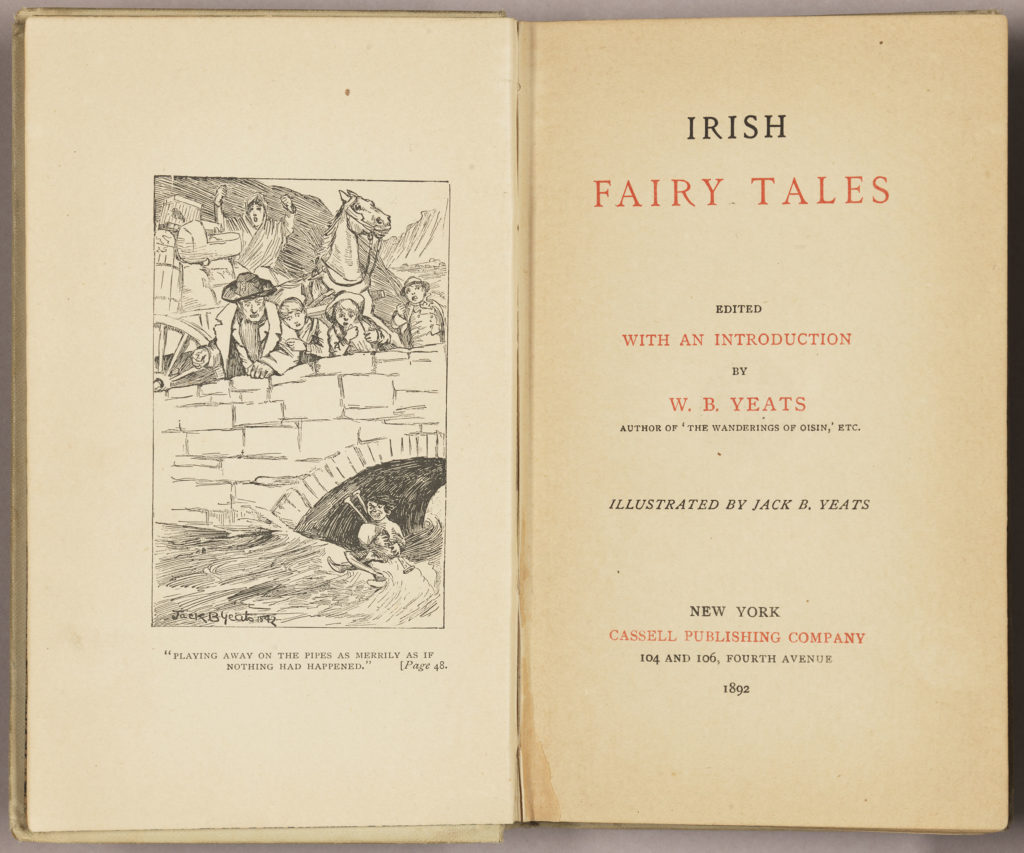

Irish Fairy Tales, edited with an introduction by W. B. Yeats. New York: Cassell, 1892.

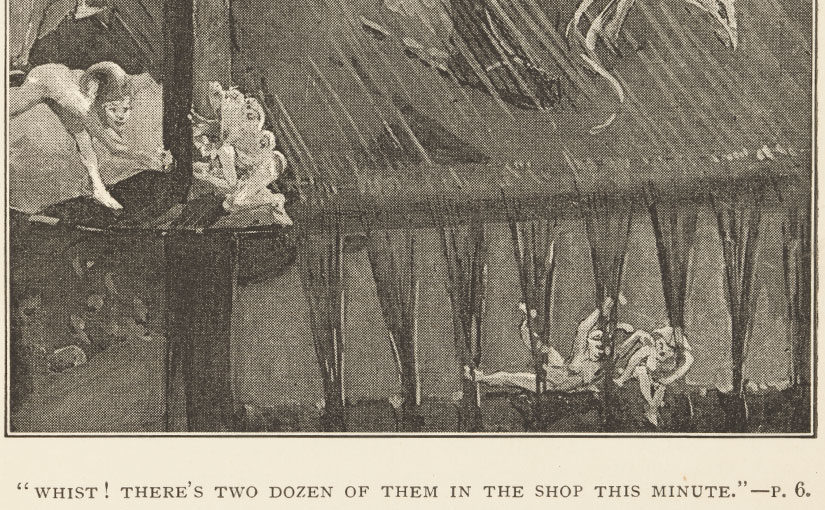

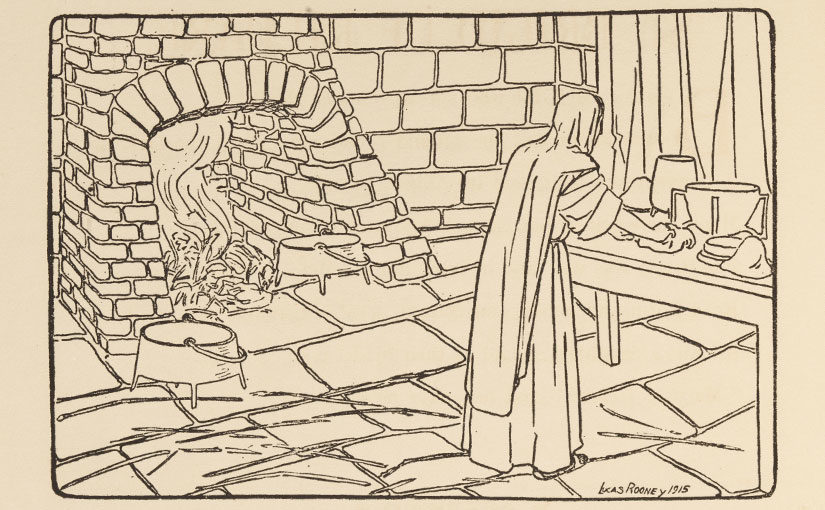

Yeats’s Irish Fairy Tales, with illustrations by his brother, Jack B. Yeats, was published in a series for children in 1892. This book has a modest selection of fourteen stories, a lively introductory essay on ‘The Irish Storyteller’, and an appendix on the classification of Irish fairies.

In a note on the contents, Yeats explains that he has included no story that has already appeared in Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, and that he believes the two volumes to make “a fairly representative collection of Irish folk tales.”

For writers of the stature of W. B. Yeats, there are usually good resources to enable librarians and scholars to research their bibliography, that is, to understand the history of their writing and their publications. In the case of Yeats, we have Allan Wade’s A Bibliography of the Writings of W. B. Yeats, 3rd. ed., rev., Russell K. Alsbach (1968). Along with what those guides can tell us, it is always interesting to examine the volumes themselves, and particularly rewarding in the case of W. B. Yeats, who made many changes in variant editions of his work.