Rare Books and Special Collections welcomes students, faculty, staff, researchers, and visitors back to campus for Fall ’21! We want to let you know about a variety of things to watch for in the coming semester.

The University of Notre Dame, Hesburgh Libraries, Special Collections, and the current COVID situation

Due to the spread of highly contagious variants of the COVID-19 virus, and our inability to verify the vaccination status of those outside our highly vaccinated campus community, masks will be required (except when eating and drinking) of both vaccinated and unvaccinated faculty, staff, students, and visitors in some campus spaces during times when those spaces are generally open to the public. The first two floors of the Hesburgh Library (including Rare Books and Special Collections) are among the spaces where masks are required in public areas, including for those who are fully vaccinated.

Up-to-date information regarding campus policies is provided at covid.nd.edu, and a complete list of these campus spaces will be updated regularly here.

New Leadership at the Hesburgh Libraries

K. Matthew Dames, previously university librarian at Boston University, has been appointed the Edward H. Arnold University Librarian at the University of Notre Dame by University President Rev. John I. Jenkins, C.S.C., effective August 1. Dr. Dames succeeds Diane Parr Walker, who has retired after serving 10 years as librarian.

Read the full press report online.

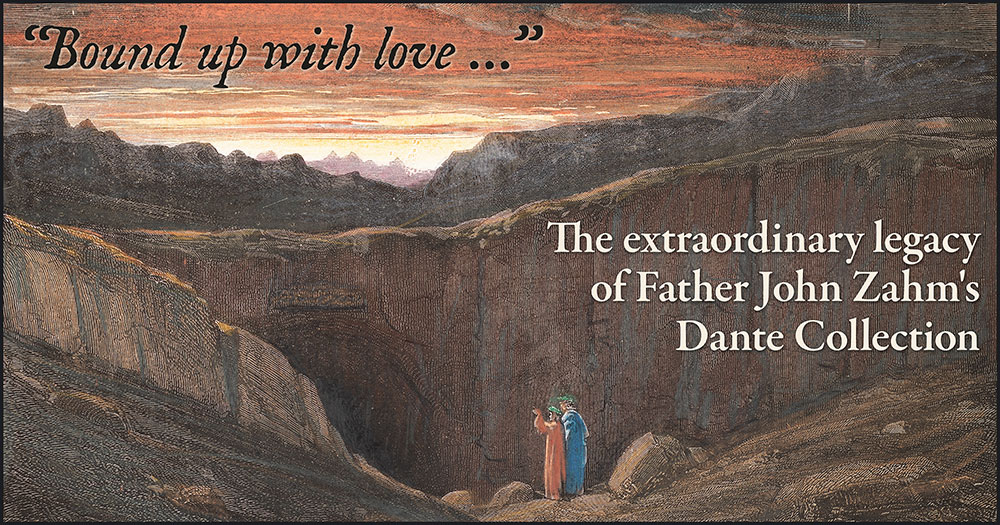

Fall 2021 exhibit: “Bound up with love …” The extraordinary legacy of Father John Zahm’s Dante Collection

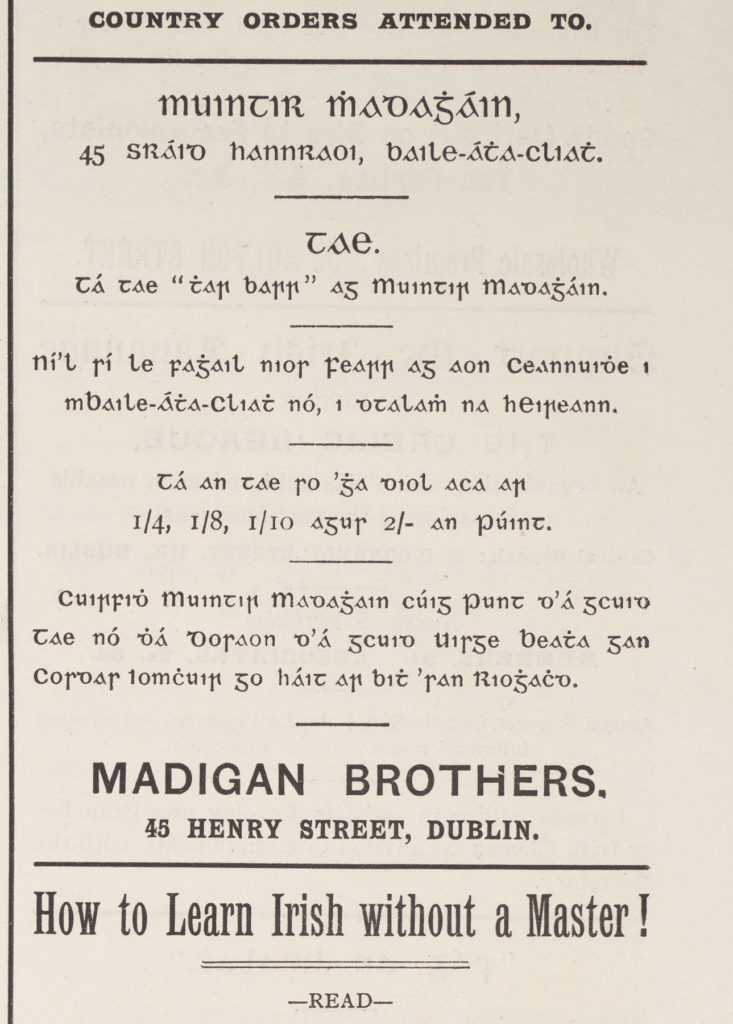

This year, the 700th anniversary of the death of Dante Alighieri, we are celebrating the legacy of the Zahm Dante Collection and the remarkable accumulation of rare Italian material acquired at the University of Notre Dame over the past century.

Highlights of the exhibition include rare printings of the three crowns of Italian literature – Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio – as well as verse anthologies of poetry and other tools such as grammars and dictionaries that would have assisted 16th century readers of vernacular literature.

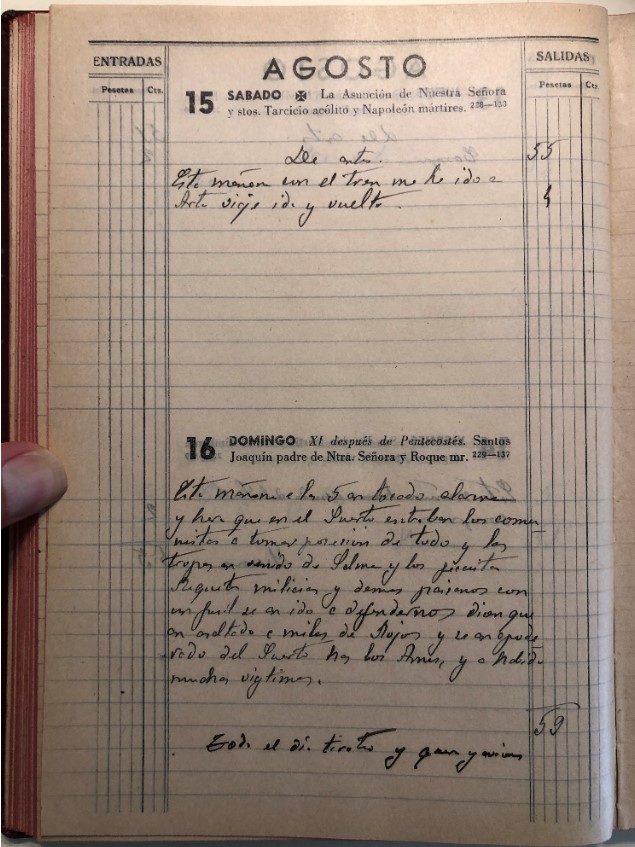

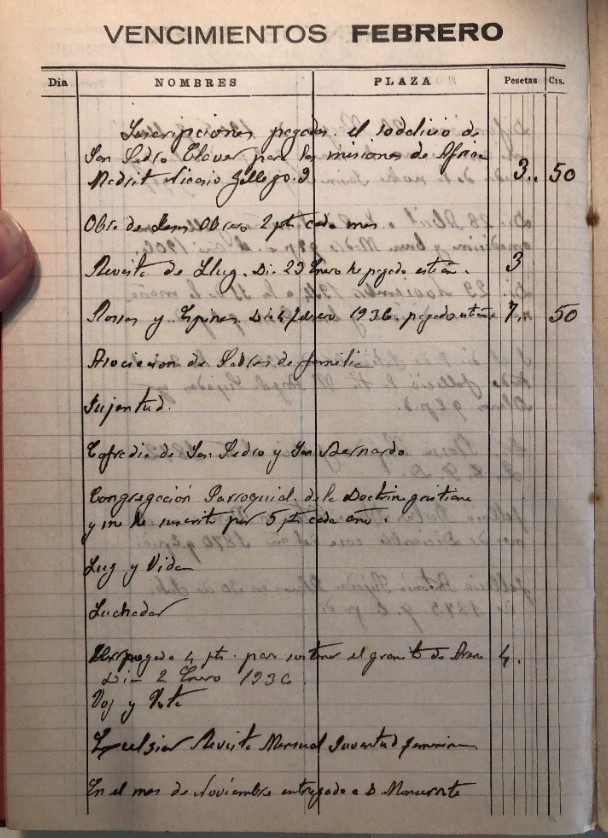

Fall 2021 Spotlight exhibit featuring the Ferrell Manuscripts

The Fall Spotlight Exhibit features six medieval manuscripts donated to the University of Notre Dame by James E. and Elizabeth J. Ferrell. The collection features a diverse group of manuscripts from the thirteenth through fifteenth century including a historiated Bible, book of hours, a tarot card, and illuminations. The Ferrell Collection can be discovered digitally.

Monthly rotating spotlight exhibits

Despite the challenges of the last academic year and thanks, in no small part, to the generosity of our donors, Special Collections’ holdings continued to grow. This spotlight exhibit celebrates one recent gift: the three-volume limited edition photo album of the Sistine Chapel. An anonymous donor presented this magnum opus to the Hesburgh Libraries in February 2021.

Drop in every month to see what new surprise awaits you in our monthly feature!

Special Collections’ Classes & Workshops

Throughout the semester, curators will teach sessions related to our holdings to undergraduate and graduate students from Notre Dame, Saint Mary’s College, and Holy Cross College. Curators may also be available to show special collections to visiting classes, from preschool through adults. If you would like to arrange a group visit and class with a curator, please contact Special Collections.

Archival Research Lab I: Locating Materials and Preparing to Go

Wednesday, October 6, 10:00am to 11:15am

Archival Research Lab II: Inside the Archive

Wednesday, October 13, 10:00am to 11:15am

This two-session workshop provides an introduction to advanced archival research. In session one, you will learn strategies for finding and evaluating relevant archival collections and steps you’ll need to consider before you go to an archive. In session two, you will “enter the archive,” completing the registration process and handling and examining different archival materials and formats. This workshop is designed to introduce those who have not previously done archival research to the world of archives and special collections, and also as a refresher and skill-building opportunity for those planning to visit archives again in the post-COVID environment.

Events

Fall 2021 Lecture Series: Dante in America — In commemoration of the 700th anniversary of Dante’s death, in 2021 the Center for Italian Studies and Devers Family Program in Dante Studies are hosting a series of lectures on the topic “Dante in America.” During the Fall Semester, the lectures are open to the public and will be held in person and streamed via Zoom, with the first lecture Thursday, September 2, 4:30pm to 6:30pm.

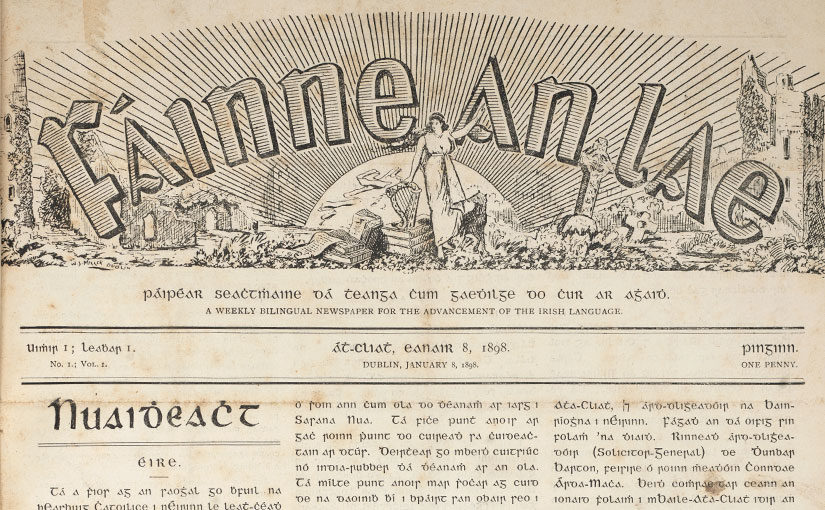

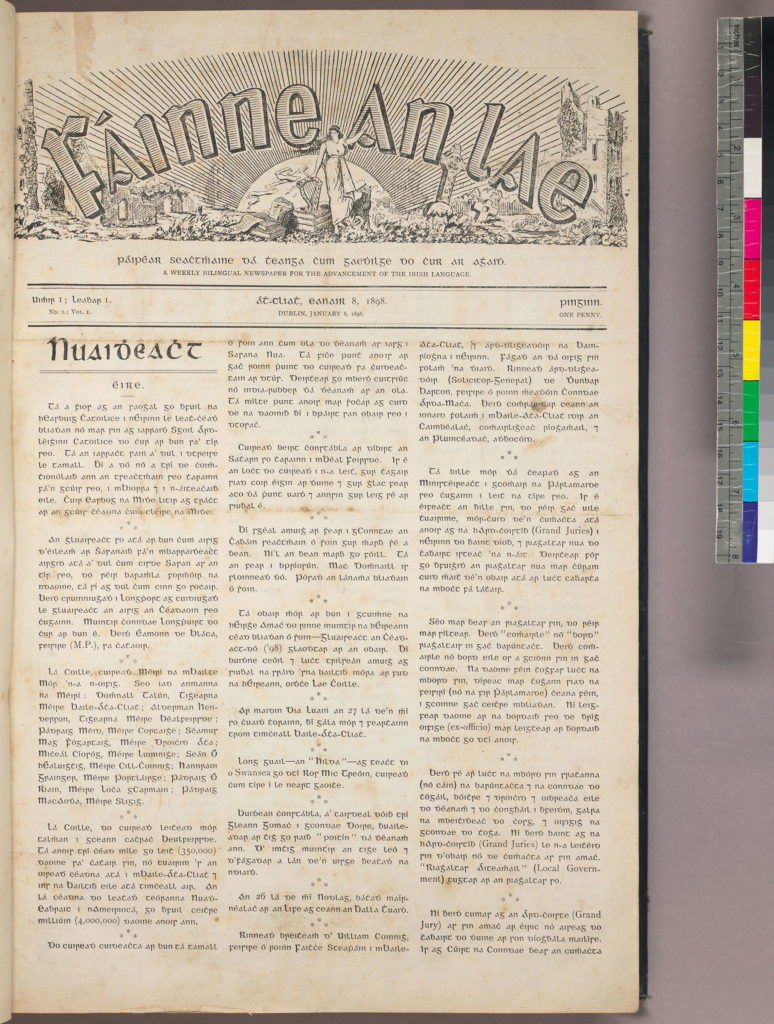

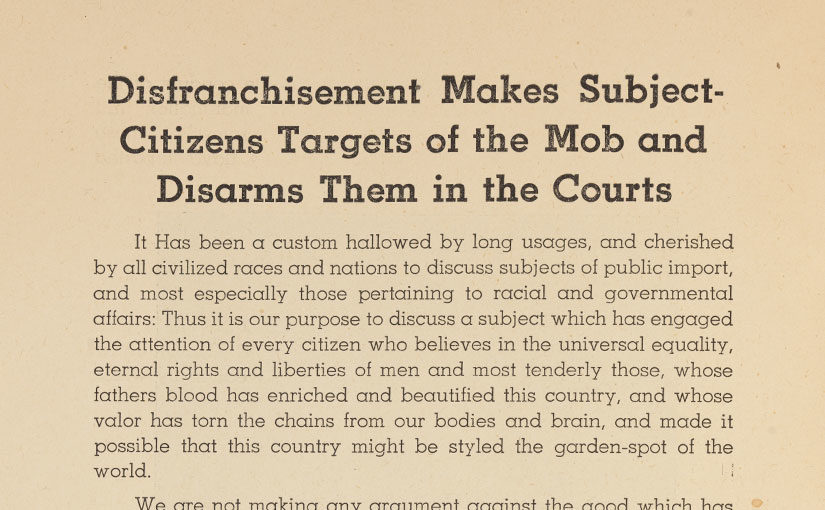

Recent Acquisitions

Special Collections acquires new material throughout the year. Watch our blog for announcements about recent acquisitions.