by Sara Weber, Special Collections Digital Project Specialist

From ghoulies and ghosties

And long-leggedy beasties

And things that go bump in the night,

Good Lord, deliver us!

Traditional Scottish Prayer

“What do you have in Special Collections?” is a question we are asked quite regularly. While we don’t have any ghosts (that we know of), we do have books that contain ghost stories. Whether a central character intended to frighten the reader or a convenient plot device, ghosts appear in a variety of works of fiction. Listed here are a selection of such stories to be found in our rare books.

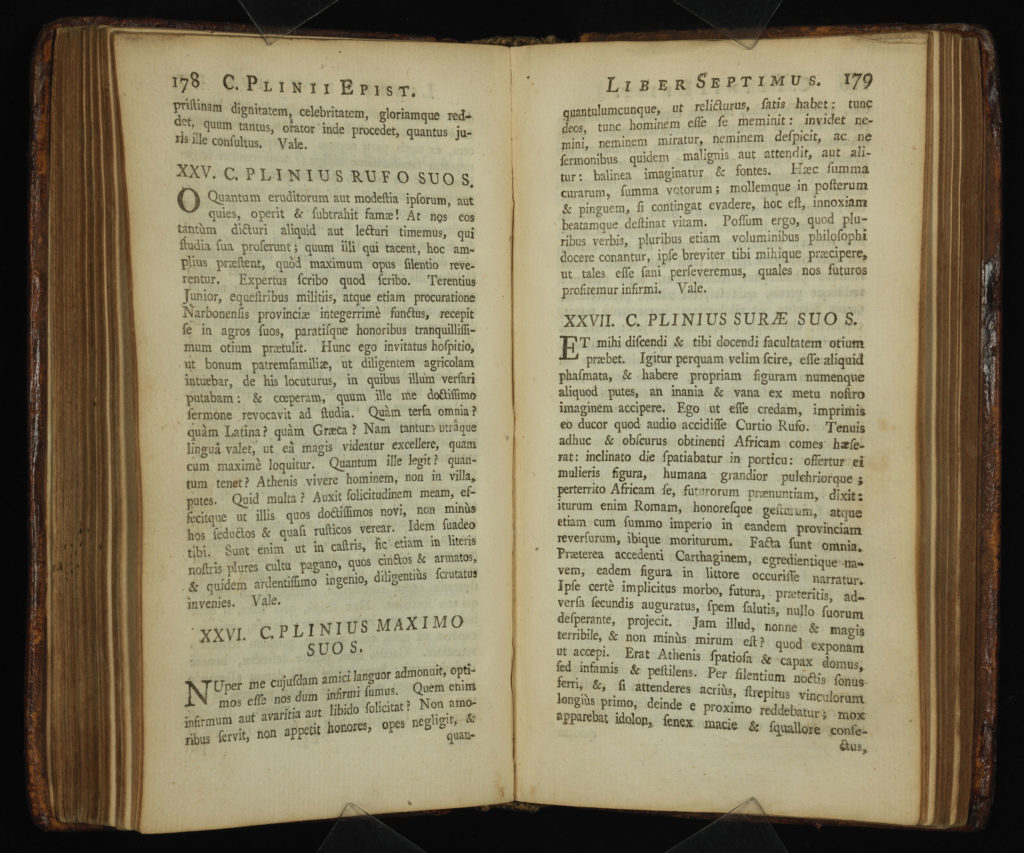

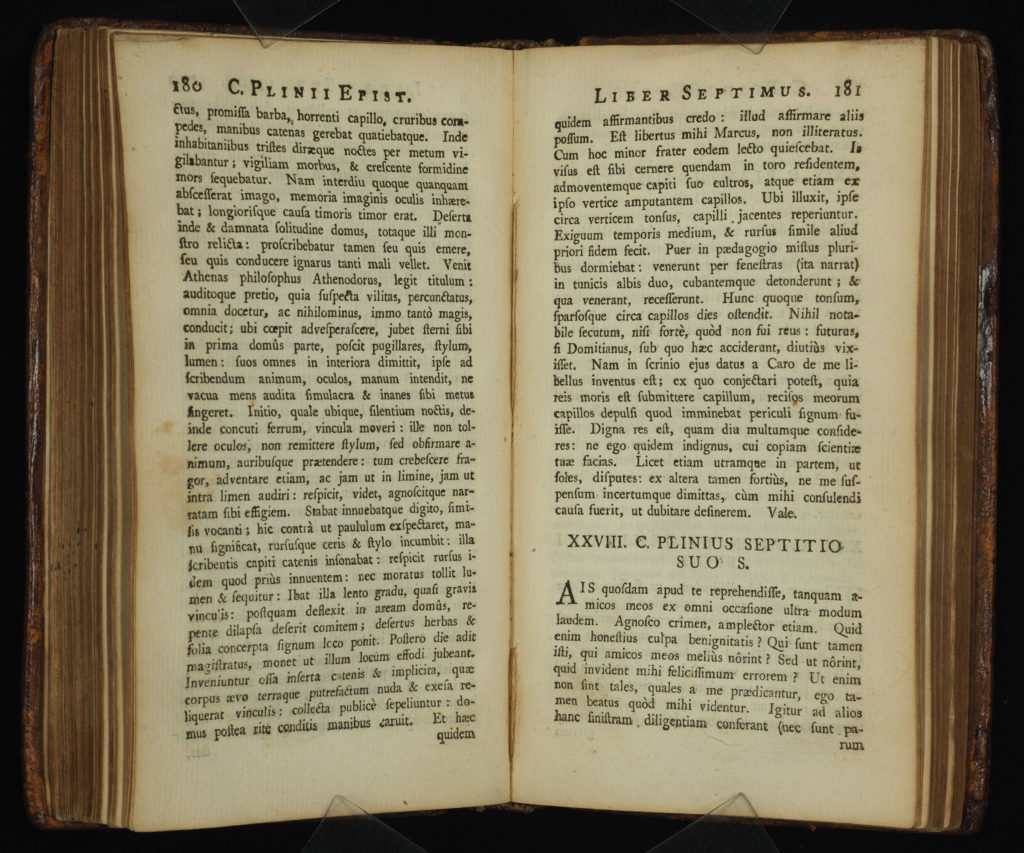

One of the earliest recorded ghost stories is that told by Pliny the Younger in his Letters, written in the early 2nd century AD. He repeats a story he has heard told of an Athenian phantom “in the form of an old man . . . with a long beard and bristling hair” [Book 7, Letter 27].

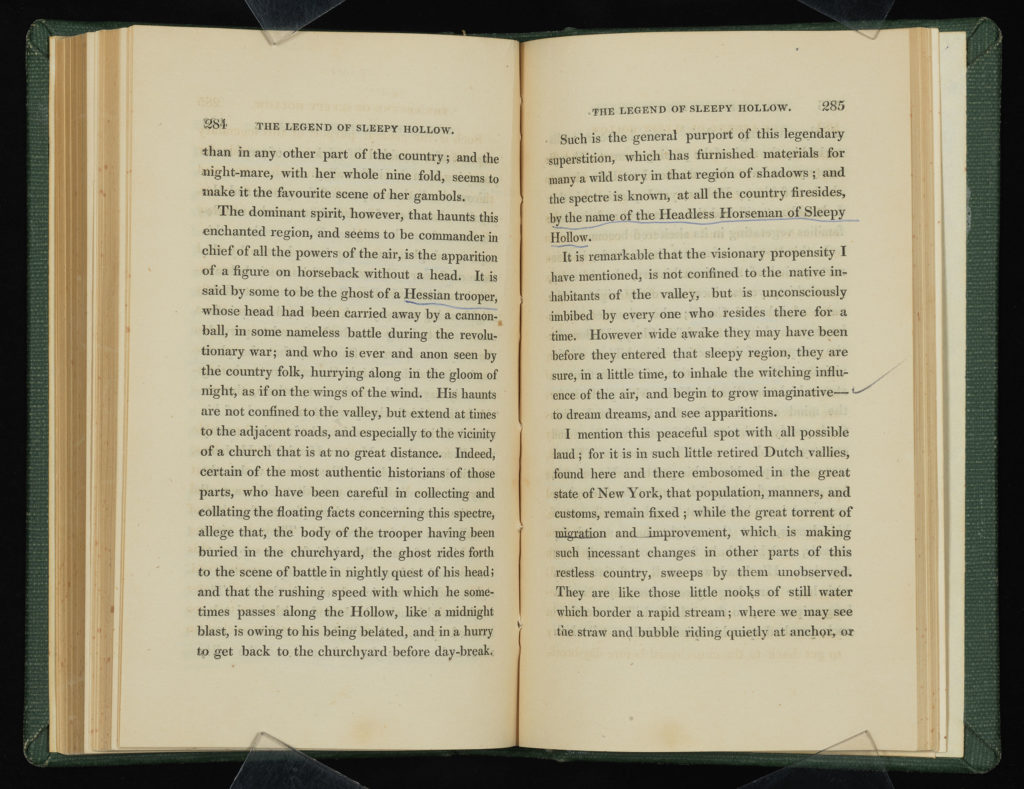

“The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” from The sketch book of Geoffrey Crayon, gent, by Washington Irving (London: J. Murray, 1821).

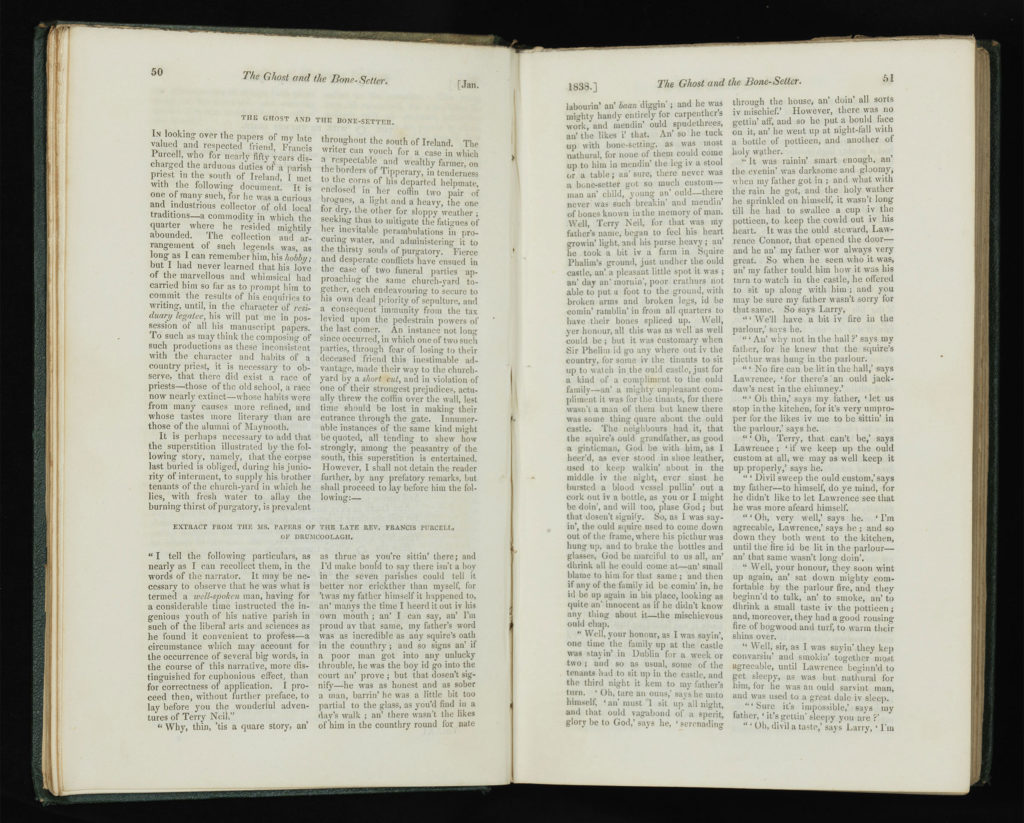

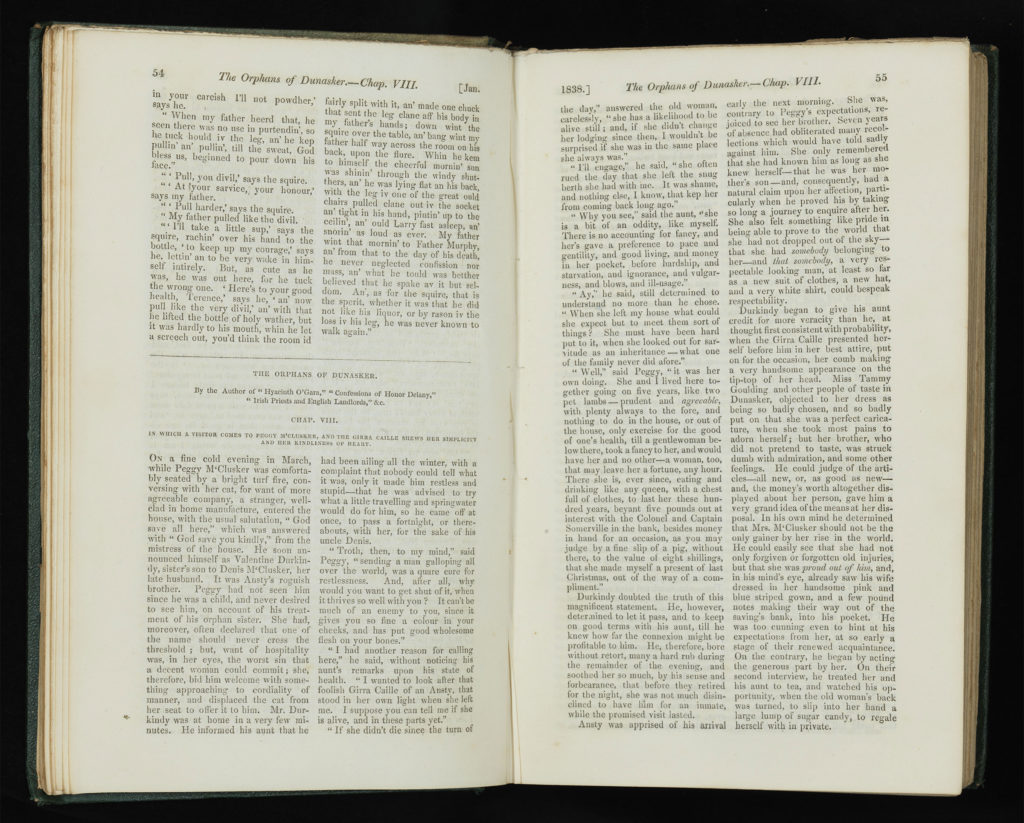

“The Ghost and the Bonesetter” by Sheridan Le Fanu, first published in 1838 in the Dublin University Magazine (Dublin, Ireland: William Curry, Jun., and Co.; and London: Simpkin and Marshall).

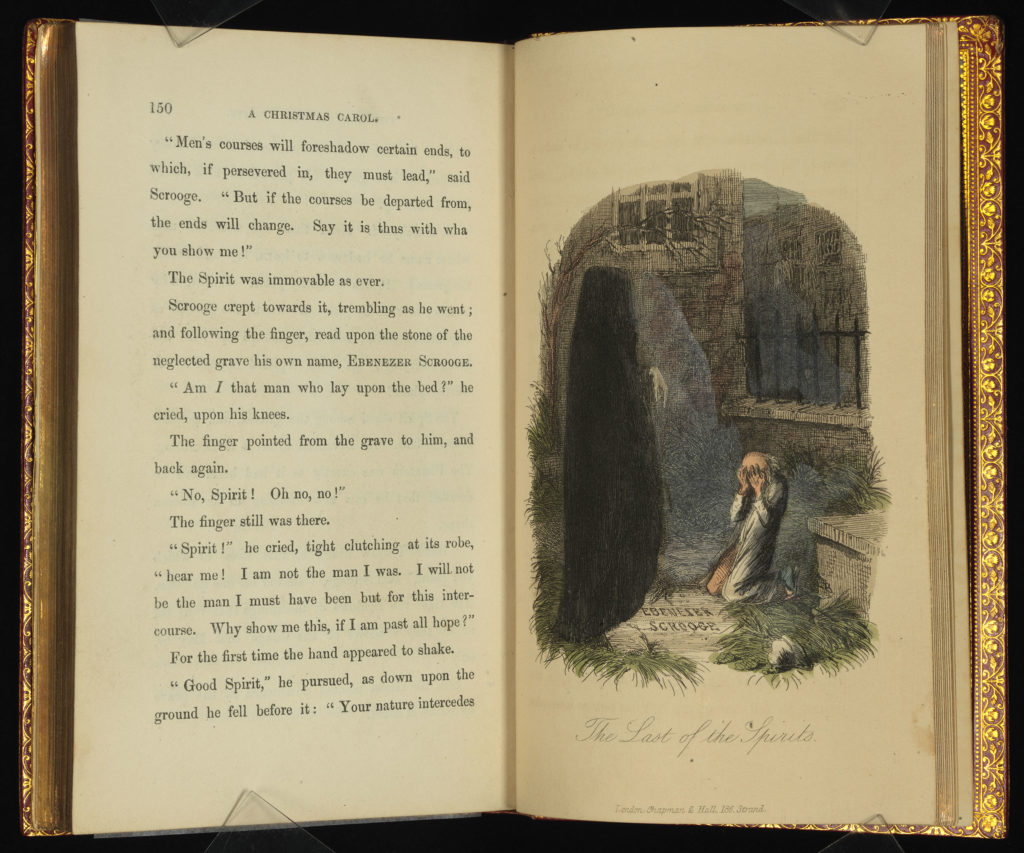

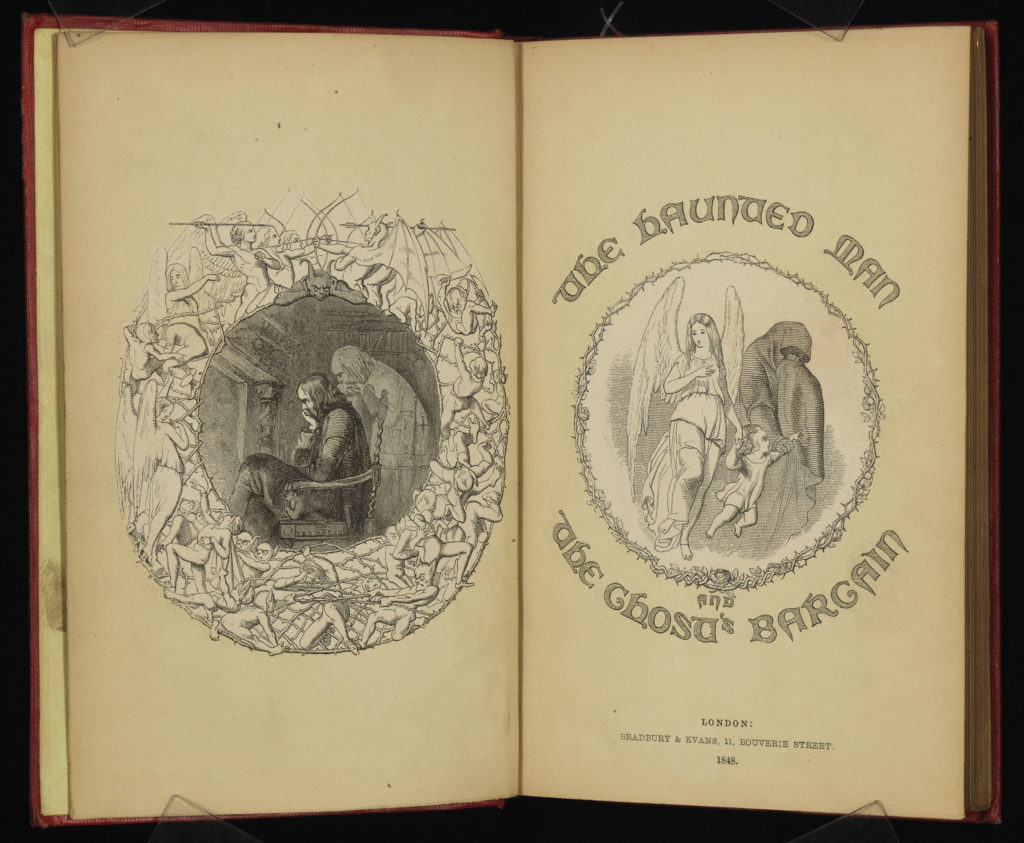

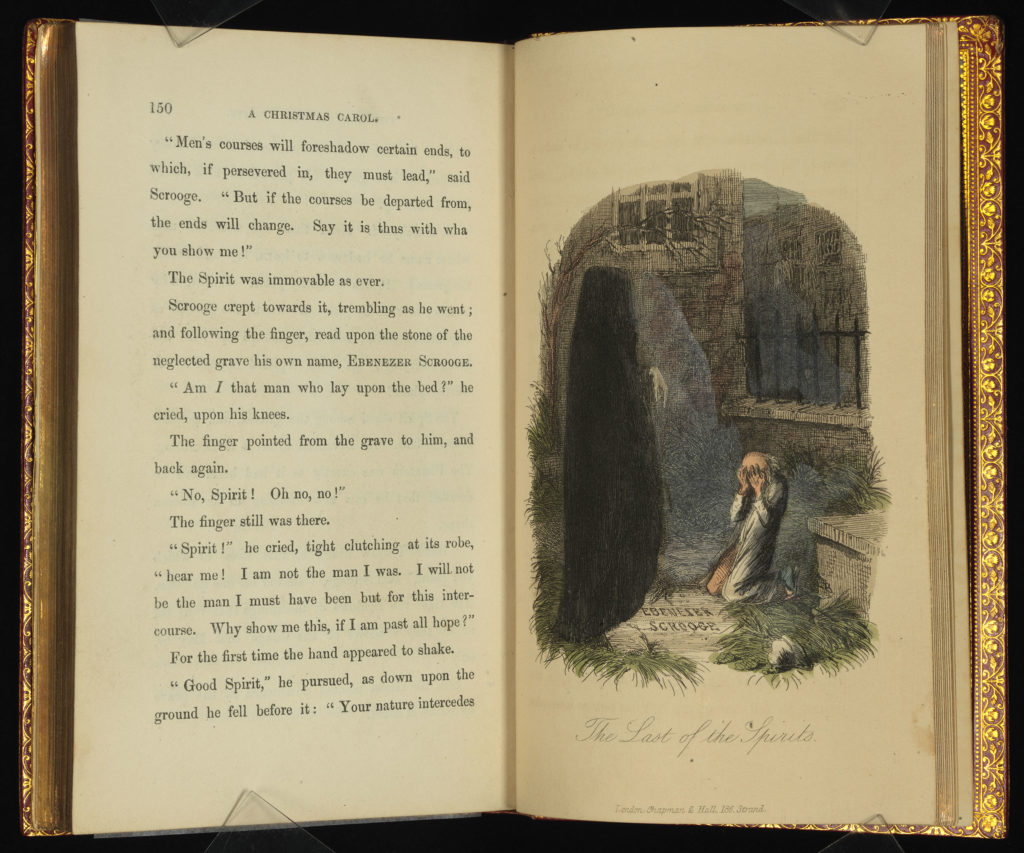

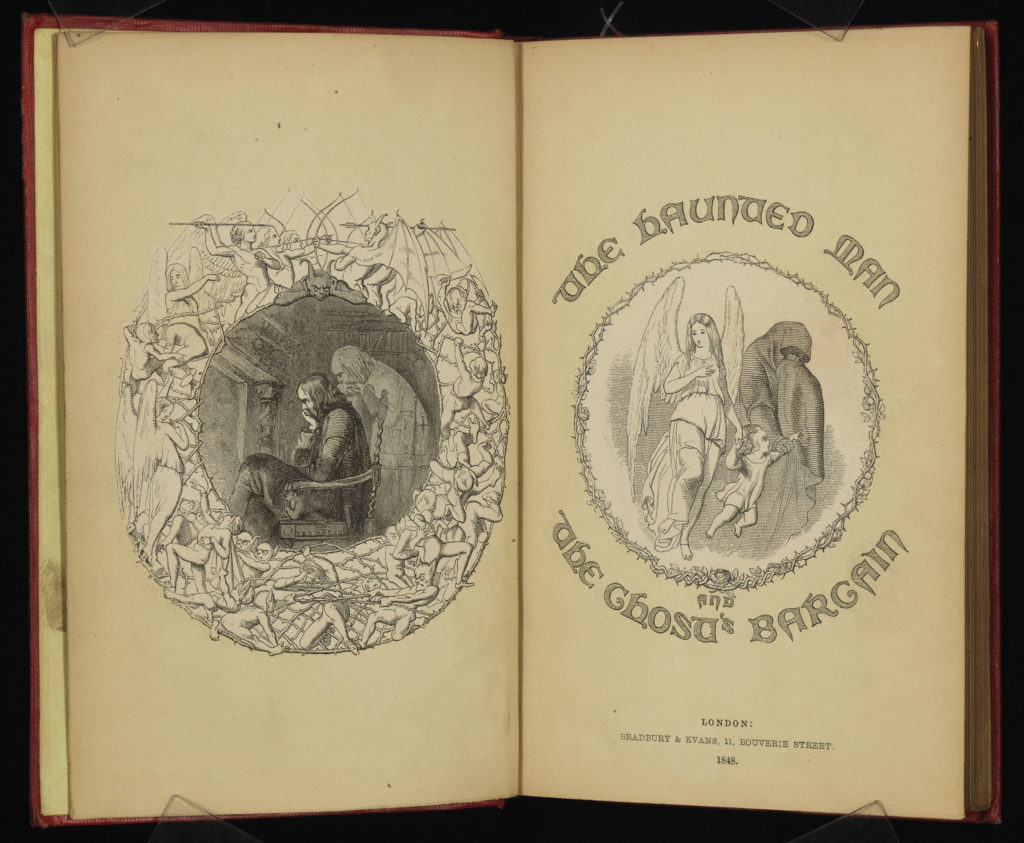

A Christmas Carol (London: Chapman & Hall, 1843) and The haunted man and the ghost’s bargain (London: Bradbury & Evans, 1848), both by Charles Dickens. Although a tradition that has nearly disappeared, telling ghost stories on Christmas Eve was popular during the Victorian era.

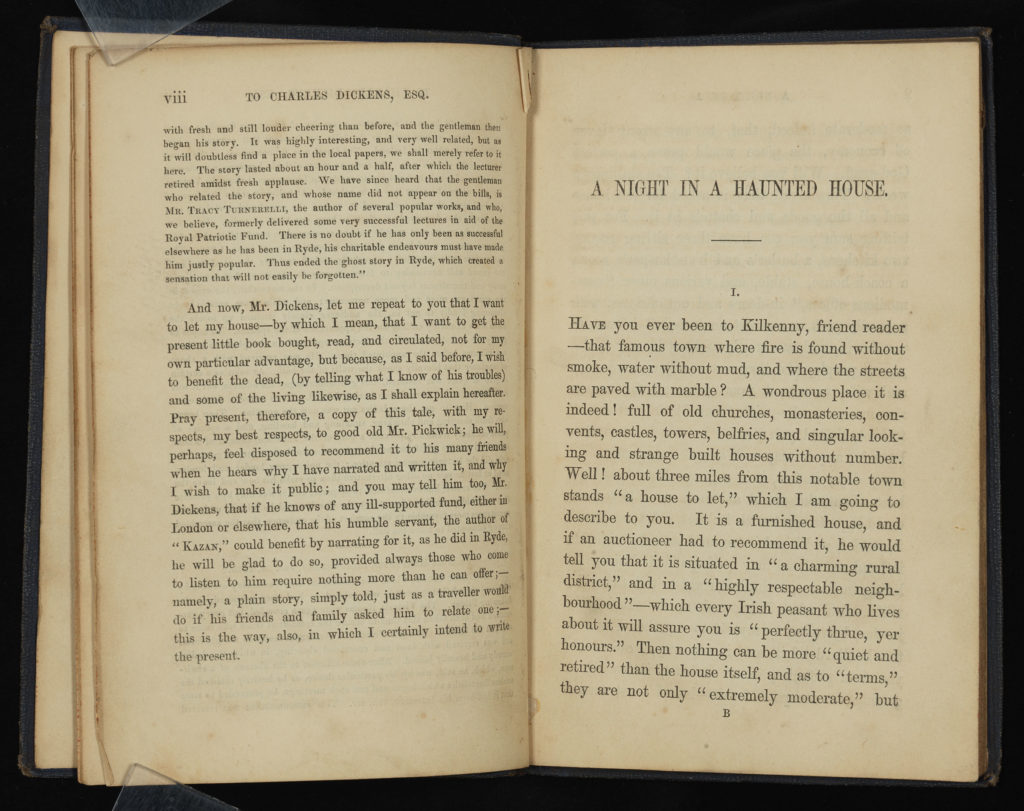

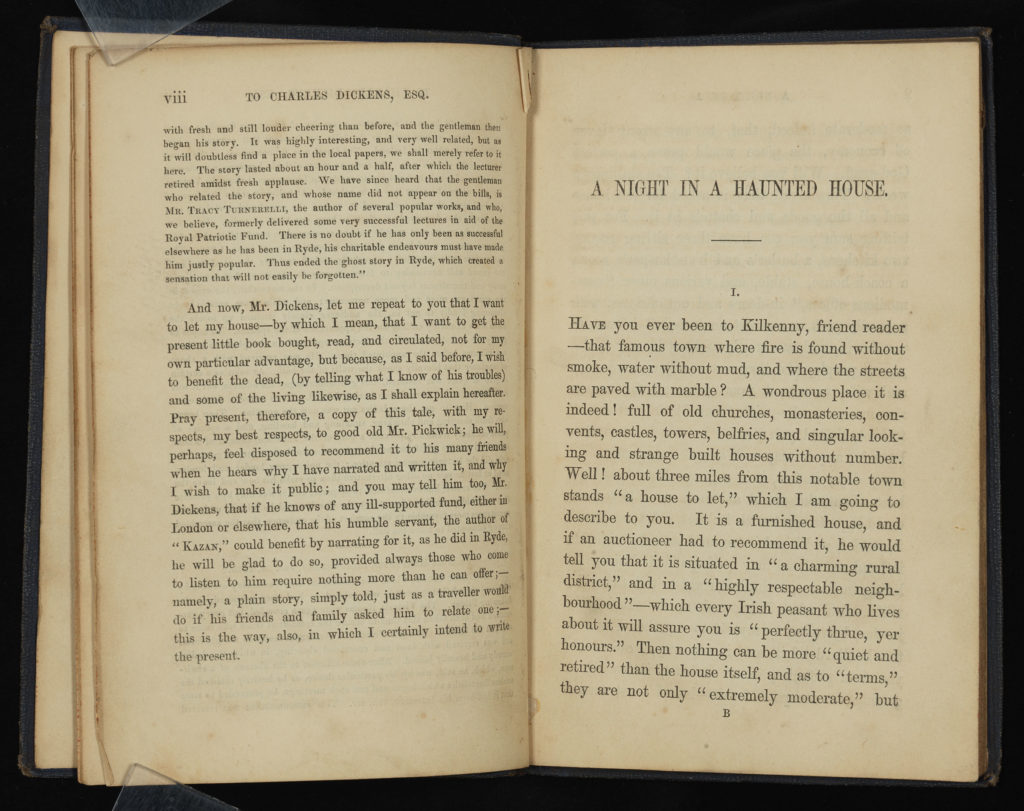

A night in a haunted house: a tale of facts, by Edward Tracy Turnerelli (London: Ward & Lock, 1859).

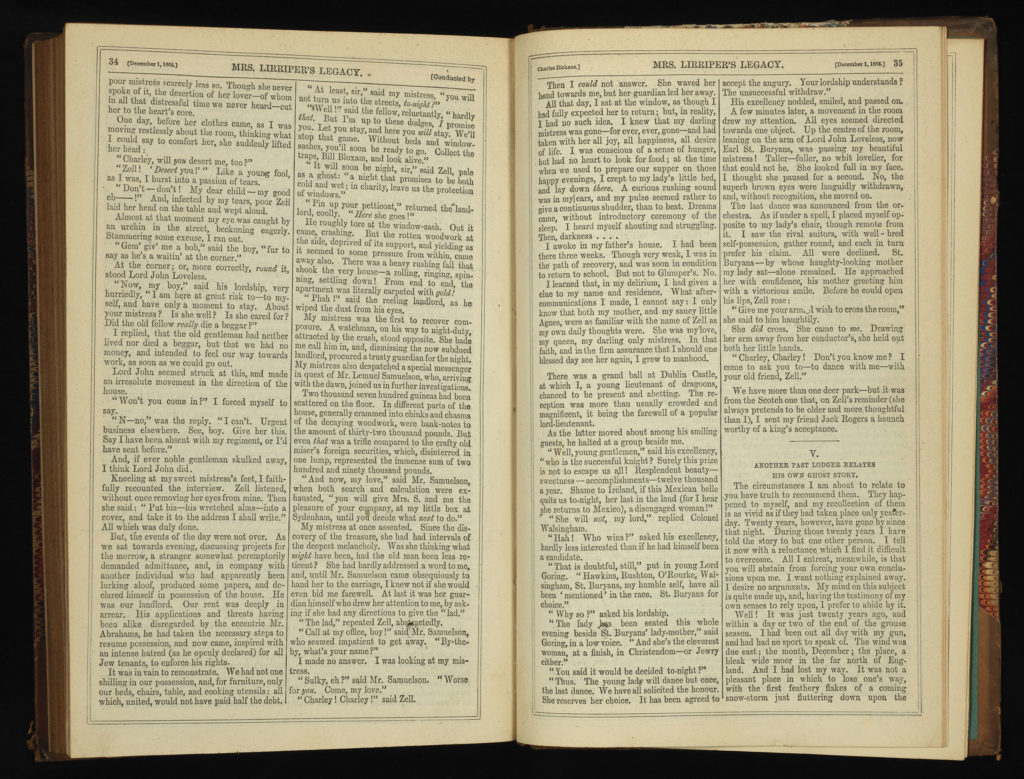

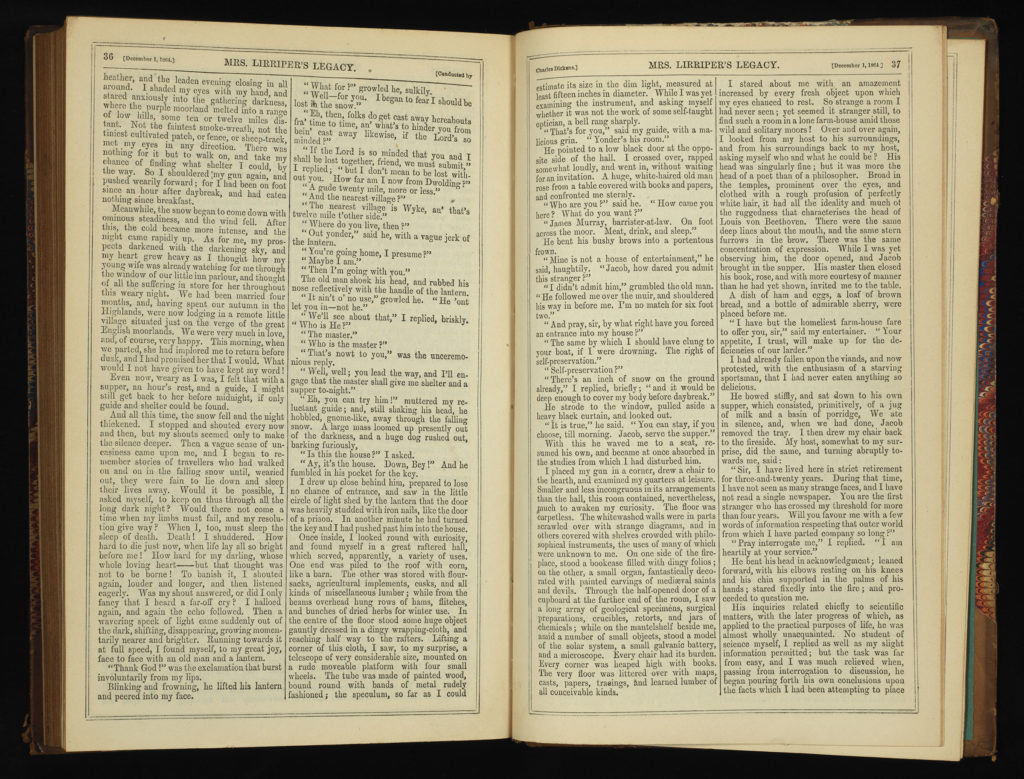

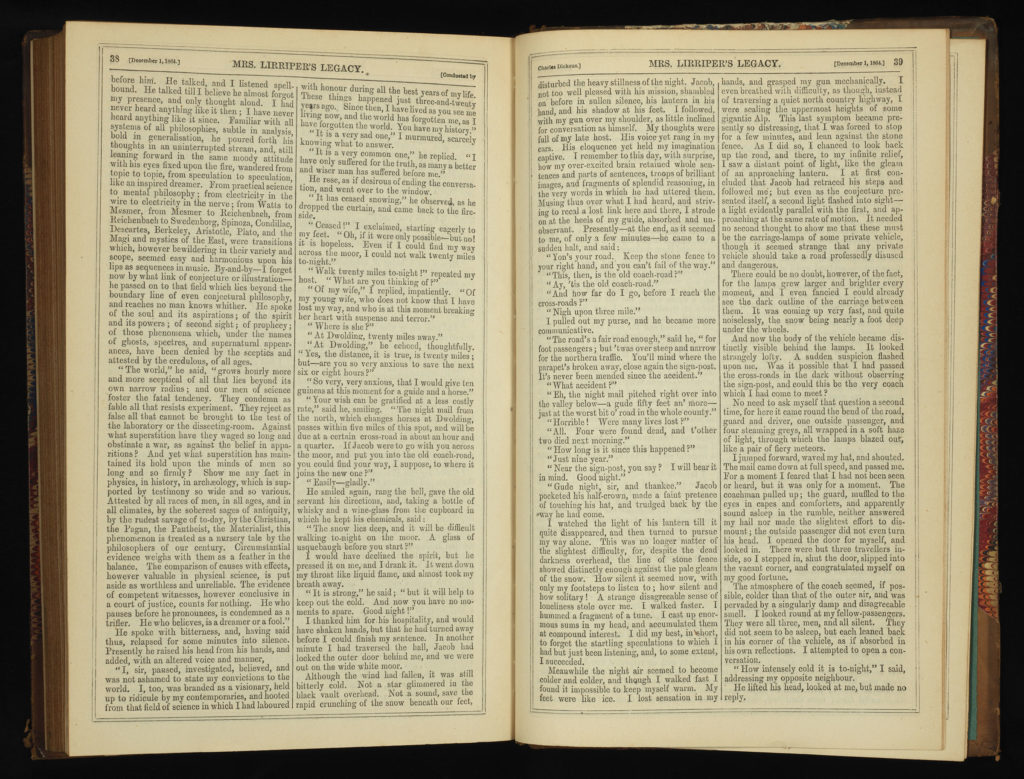

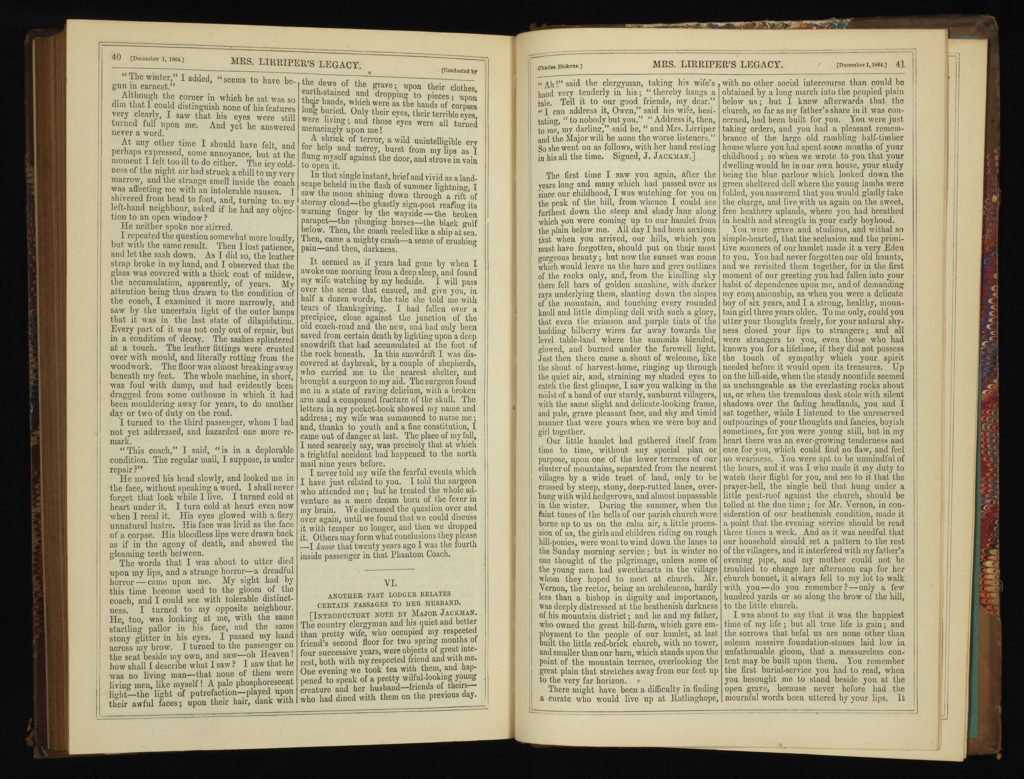

“The Phantom Coach” by Amelia Edwards, first published December 1864 in the Extra Christmas Number “Mrs. Lirriper’s Legacy” issue of All the year Round, a Victorian periodical edited by Charles Dickens (London: Chapman and Hall, 1859-1895). Many 19th century ghost stories were initially published in magazines.

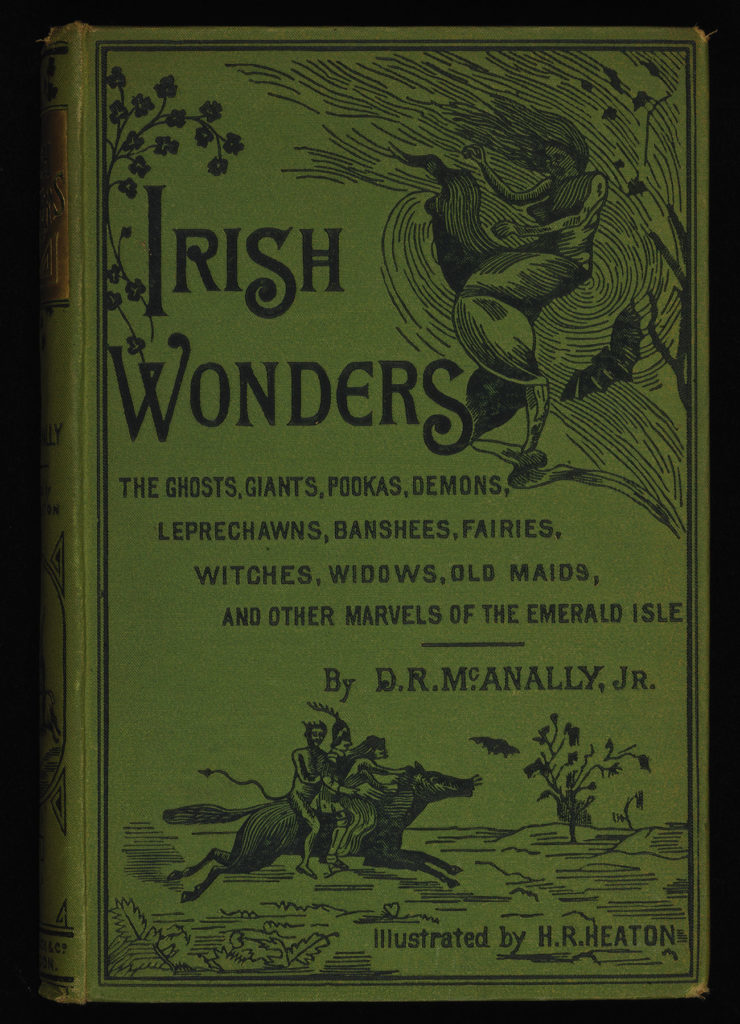

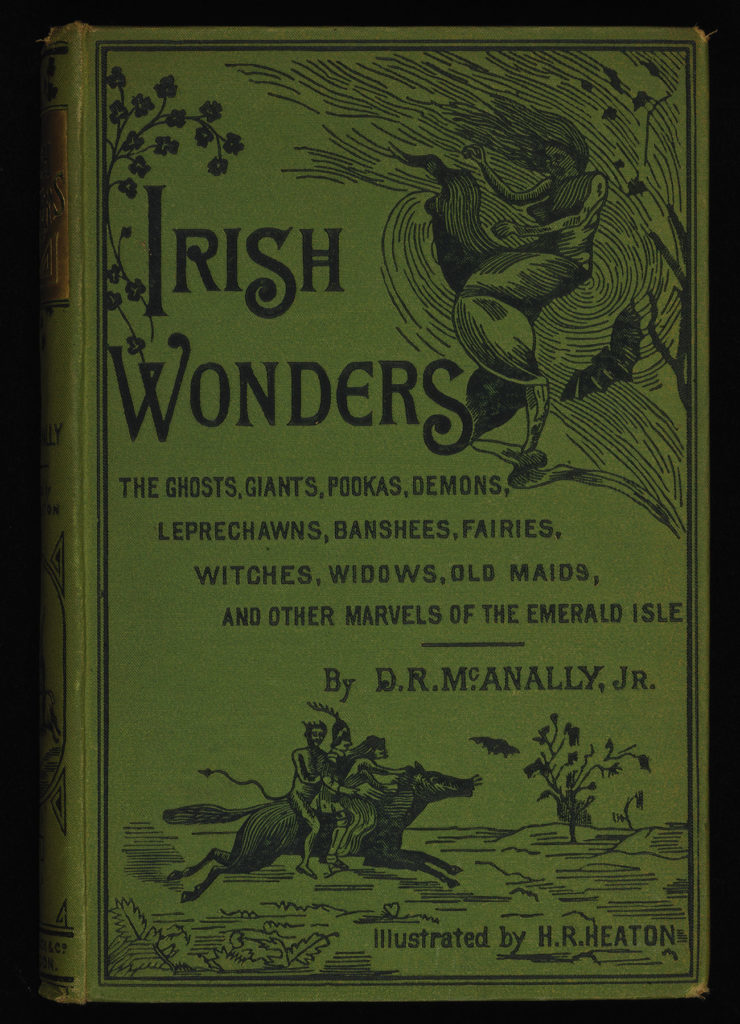

Irish wonders: the ghosts, giants, pookas, demons, leprechauns, banshees, fairies, witches, widows, old maids, and other marvels of the Emerald Isle, by David Rice McAnally (London: Ward, Lock, 1888).

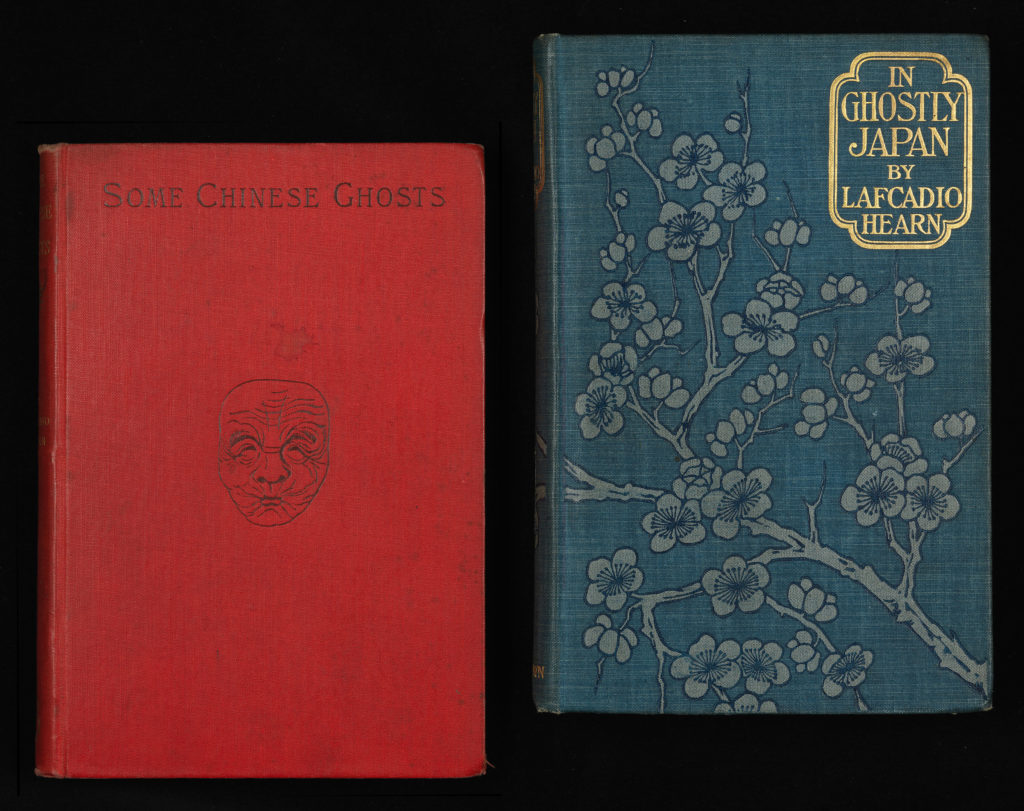

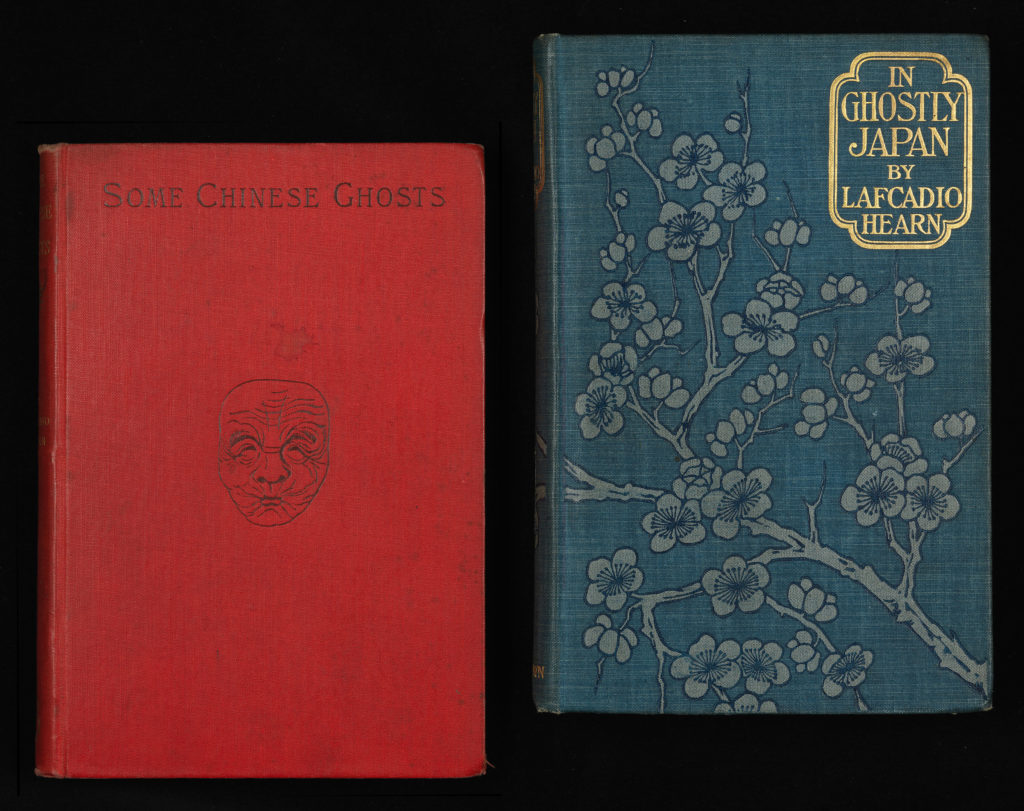

Some Chinese ghosts (Boston: Roberts brothers, 1887) and In ghostly Japan (Boston: Little, Brown and Co. 1899), both by Lafcadio Hearn.

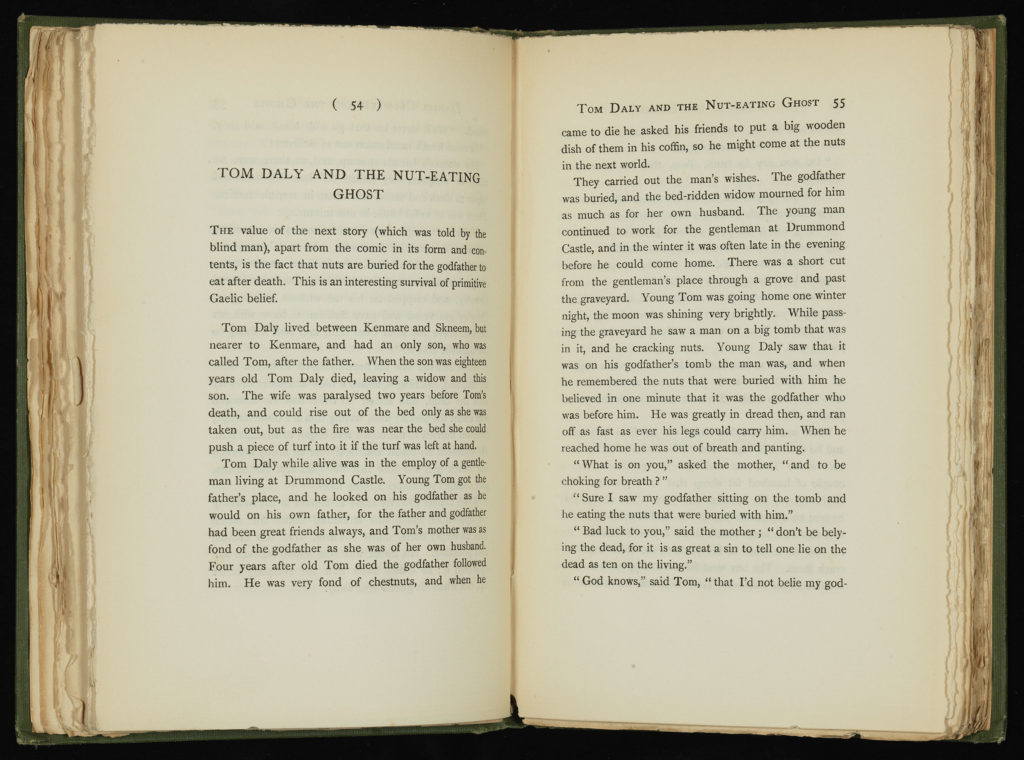

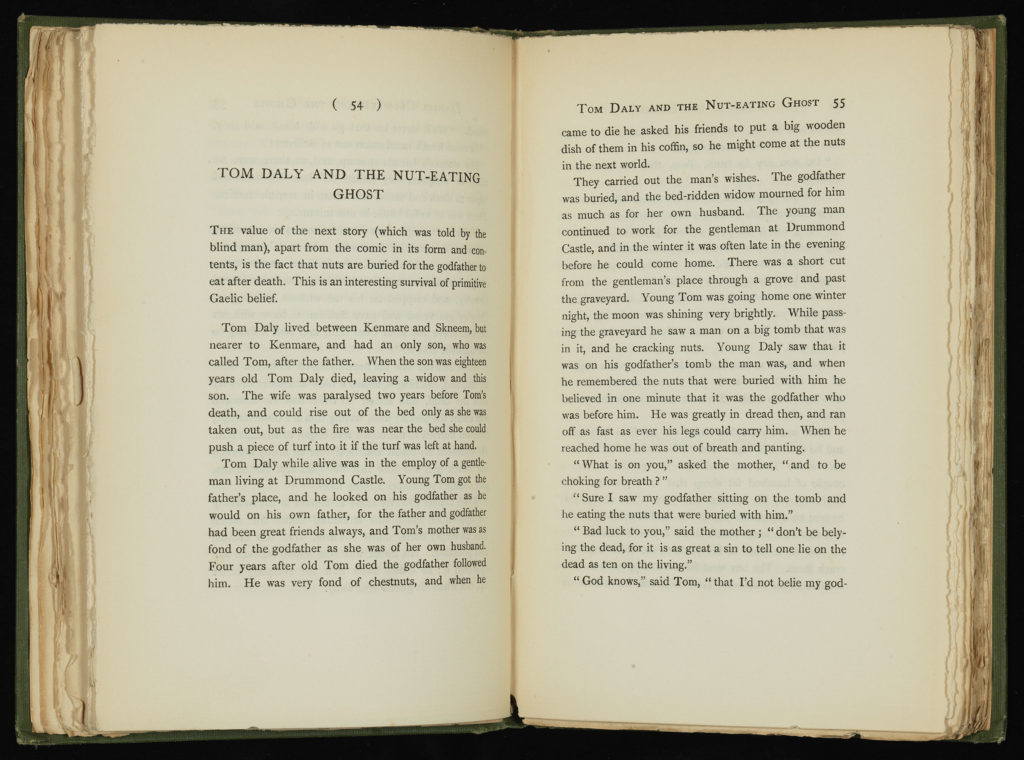

“Tom Daly and the nut-eating ghost” from Tales of the fairies and of the ghost world, collected from the oral tradition in South-west Munster, by Jeremiah Curtin (London: D. Nutt, 1895).

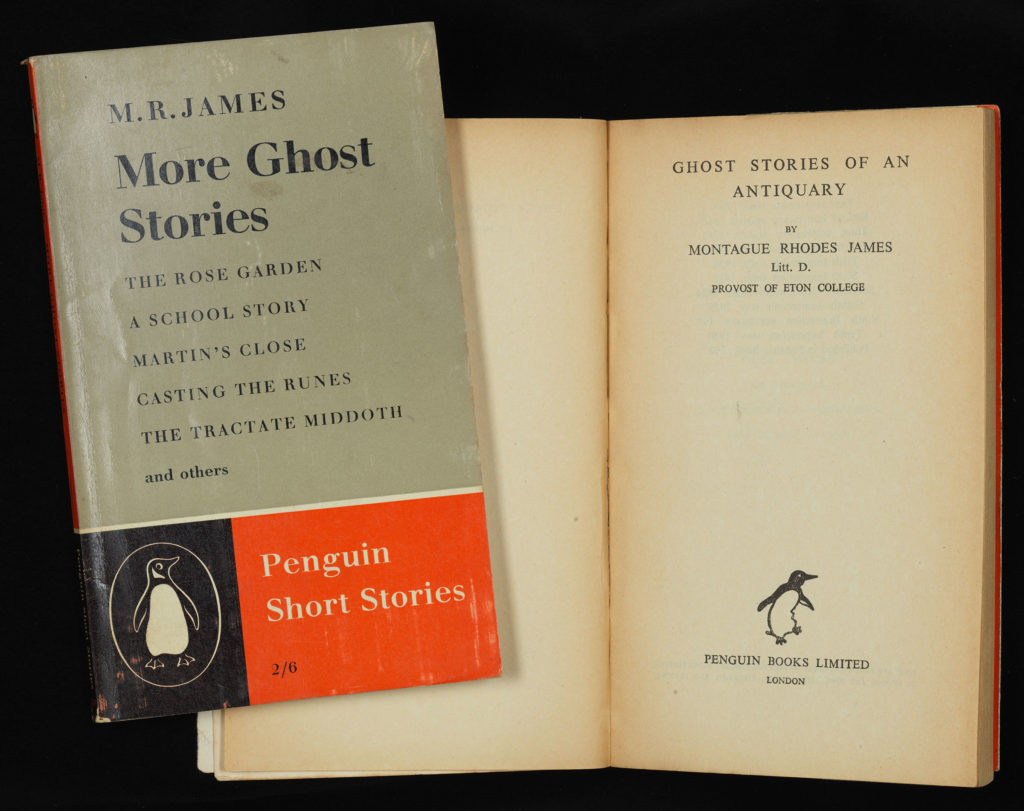

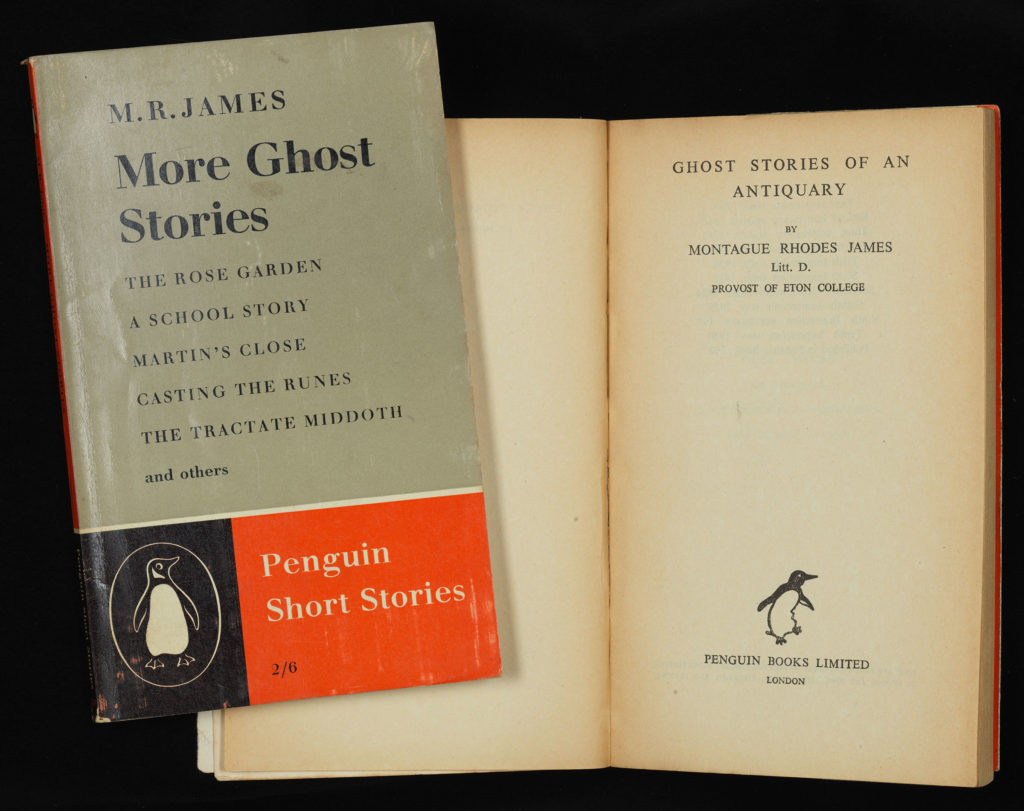

M. R. James’s Ghost stories of an antiquary (London: Penguin Books, 1937) and More ghost stories (Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1959). James’s first and second collections of ghost stories, these were originally published in 1904 and 1911, respectively.

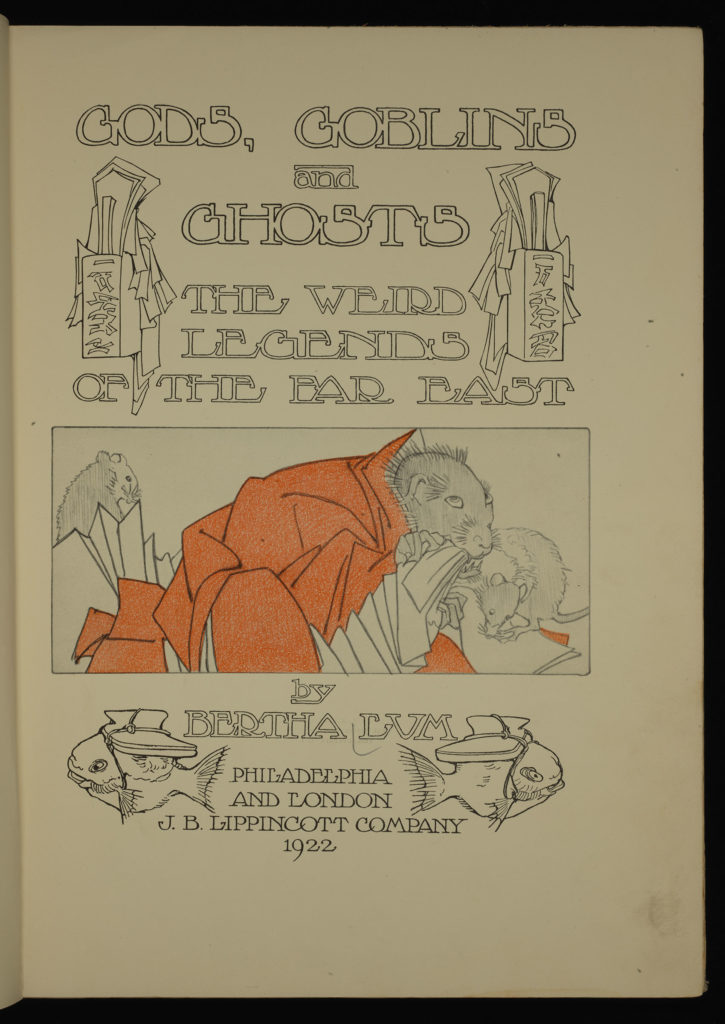

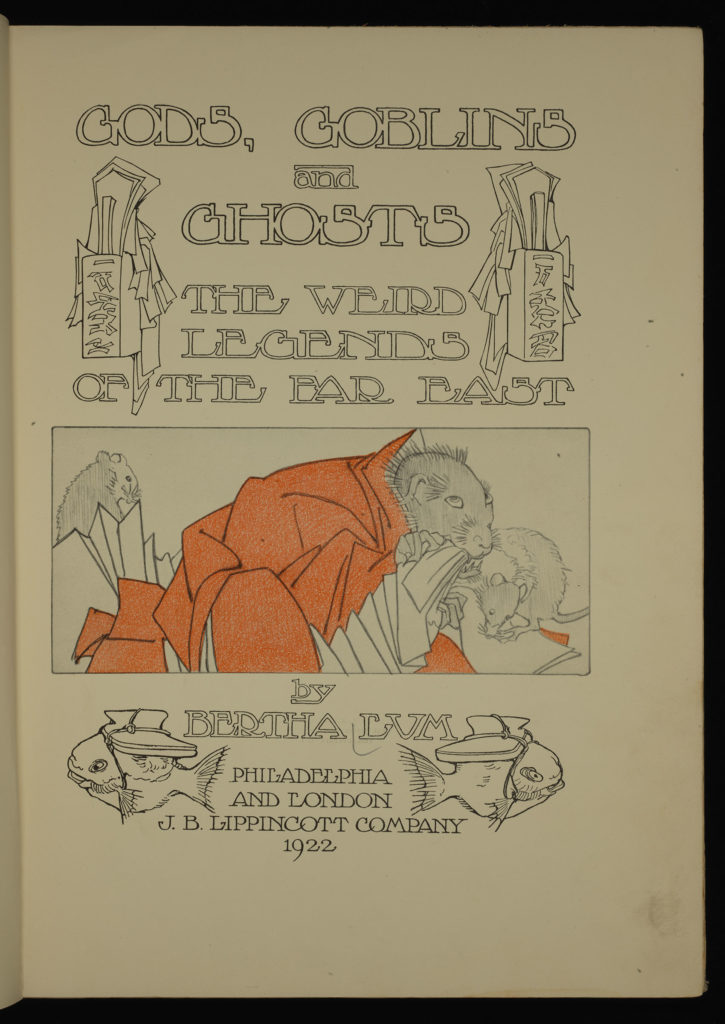

Gods, goblins and ghosts; the weird legends of the Far East, by Bertha Lum (Philadelphia and London: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1922).

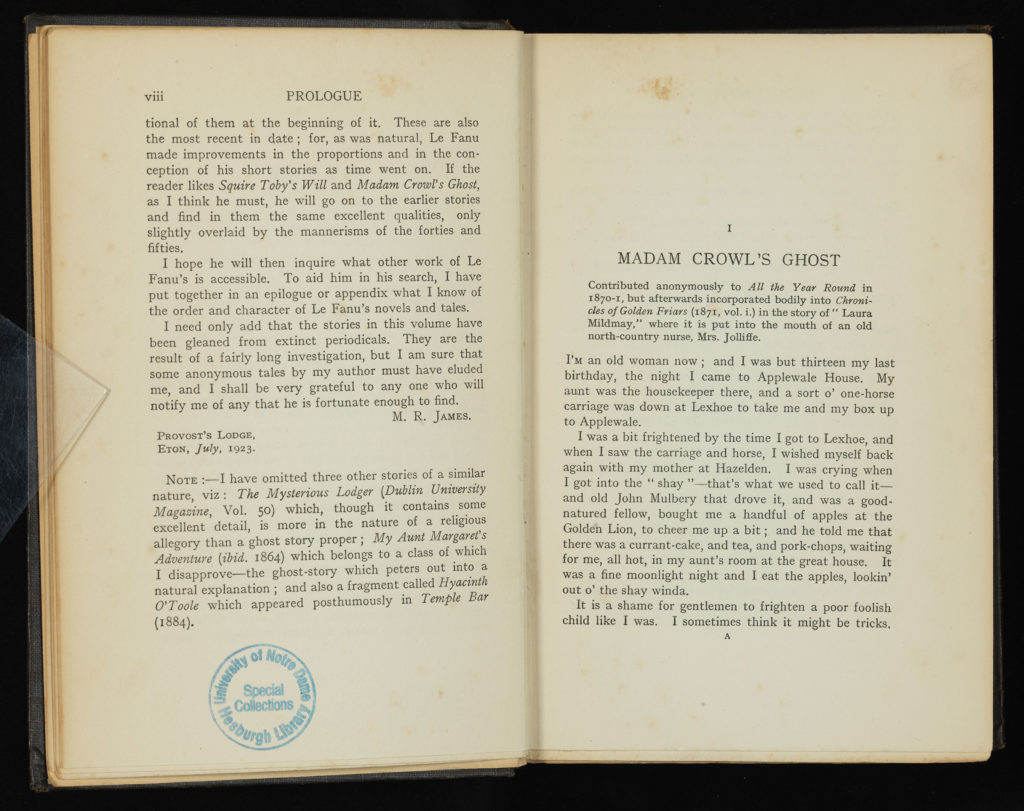

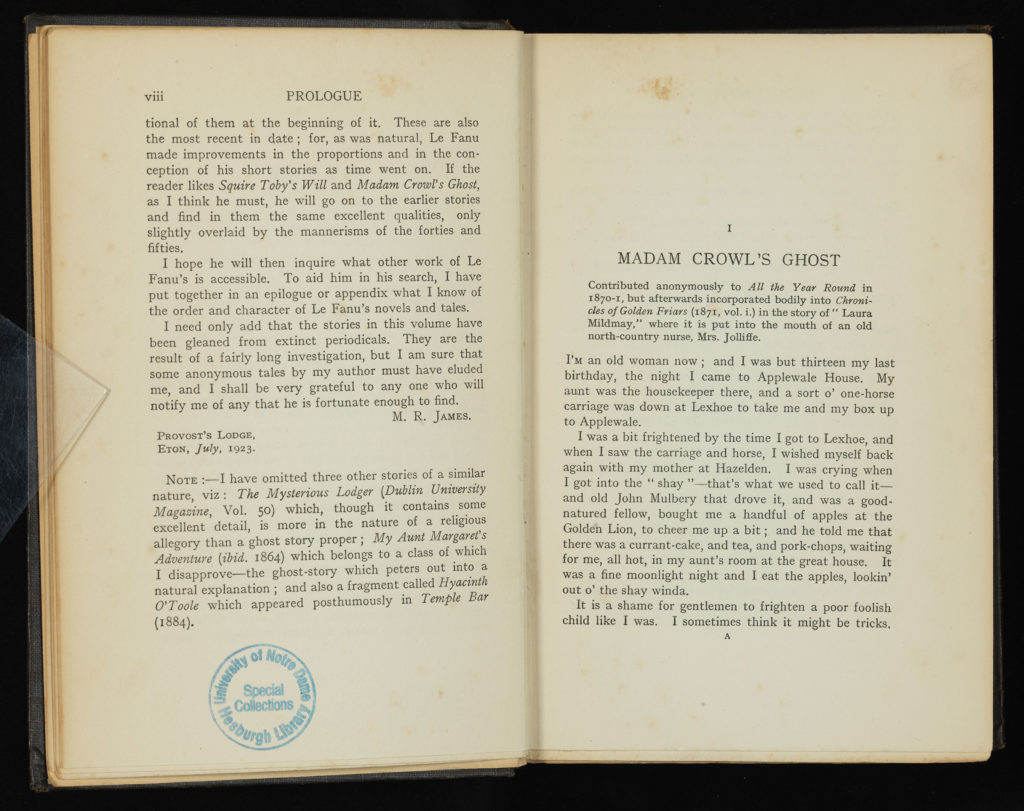

Madam Crowl’s ghost: and other tales of mystery, by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, edited by M. R James (London: G. Bell and sons, ltd., 1923).

Happy Haunting to you and yours from all of us in Notre Dame’s Special Collections!

P.S. If you’re curious about ghost stories here on campus, check out Notre Dame Magazine’s article “Haunt thee, Notre Dame?” from the Autumn 2009 issue.

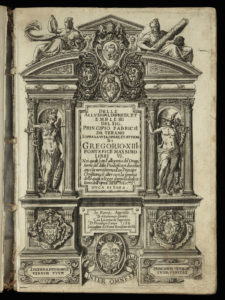

We’ve just acquired an emblem book that may be of interest to Catholic Reformation researchers, Principio Fabricii’s Delle allusioni, imprese, et emblemi del. sig. Principio Fabricii da Teramo sopra la vita,opere, et attioni di Gregorio XIII pontefice massimo libri VI (Rome, 1588). This first edition contains 231 numbered emblems, drawn from the Bible, classical mythology, and other emblem collections, as well as events and buildings from Pope Gregory XIII’s papacy.

We’ve just acquired an emblem book that may be of interest to Catholic Reformation researchers, Principio Fabricii’s Delle allusioni, imprese, et emblemi del. sig. Principio Fabricii da Teramo sopra la vita,opere, et attioni di Gregorio XIII pontefice massimo libri VI (Rome, 1588). This first edition contains 231 numbered emblems, drawn from the Bible, classical mythology, and other emblem collections, as well as events and buildings from Pope Gregory XIII’s papacy. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.