Rare Books and Special Collections is open through Friday, December 21, 2018. We will be closed for the Christmas and New Year’s Break December 24, 2018, through January 1, 2019. We will reopen on Wednesday, January 2, 2019.

Tag: on this day & holidays

Some Satirical Musings for Christmas

by Julie Tanaka, Curator, Special Collections

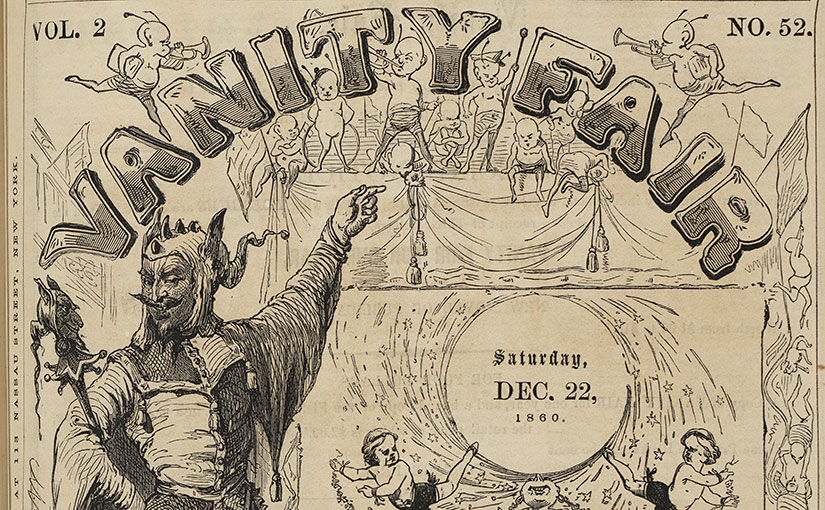

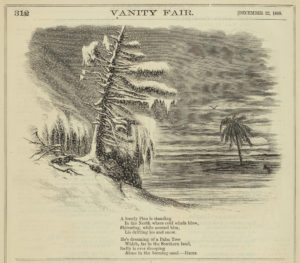

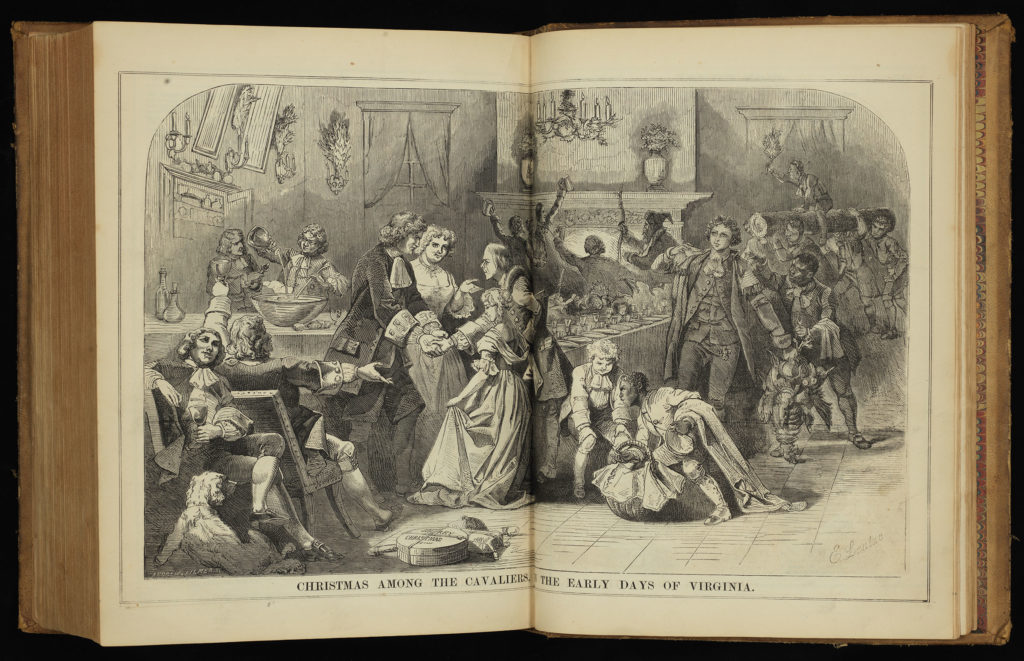

Vanity Fair, Saturday, Dec. 22, 1860—this was the first Christmas issue featuring a series of satirical columns and illustrations beginning with Richard Henry Stoddard’s account of poor, unemployed John Hardy thinking about “money, money, money” on Christmas Eve. Following this was some “Christmas Cheer” in England and a “Christmas Jingle.” Then Heine Heine’s lonely, shivering pine tree covered in snow dreaming about the palm tree in the warm southern lands. At center, a two-page spread of Virginia cavaliers celebrating the holiday.

Vanity Fair, Saturday, Dec. 22, 1860—this was the first Christmas issue featuring a series of satirical columns and illustrations beginning with Richard Henry Stoddard’s account of poor, unemployed John Hardy thinking about “money, money, money” on Christmas Eve. Following this was some “Christmas Cheer” in England and a “Christmas Jingle.” Then Heine Heine’s lonely, shivering pine tree covered in snow dreaming about the palm tree in the warm southern lands. At center, a two-page spread of Virginia cavaliers celebrating the holiday.

Vanity Fair was a popular title used for three subsequent magazines and should not be confused with the current one published by Condé Nast. The issue featured was from the American satirical magazine published by Louis Henry Stephens and edited by his brothers William Allen Stephens and Henry Louis Stephens. Vanity Fair was published with interruptions caused by problems obtaining paper on which to print between December 31, 1859 and July 4, 1863. Noted for its cartoons and satire columns, this magazine was critical of the Civil War’s progress and Abraham Lincoln’s policies.

Rare Books and Special Collections will be closed for Notre Dame’s Christmas and New Year’s Break (December 24, 2018, through January 1, 2019). We are open our regular hours during Exams, and welcome those looking for a quiet place to study.

Thanksgiving from the Margins

by Rachel Bohlmann, American History Librarian

by Rachel Bohlmann, American History Librarian

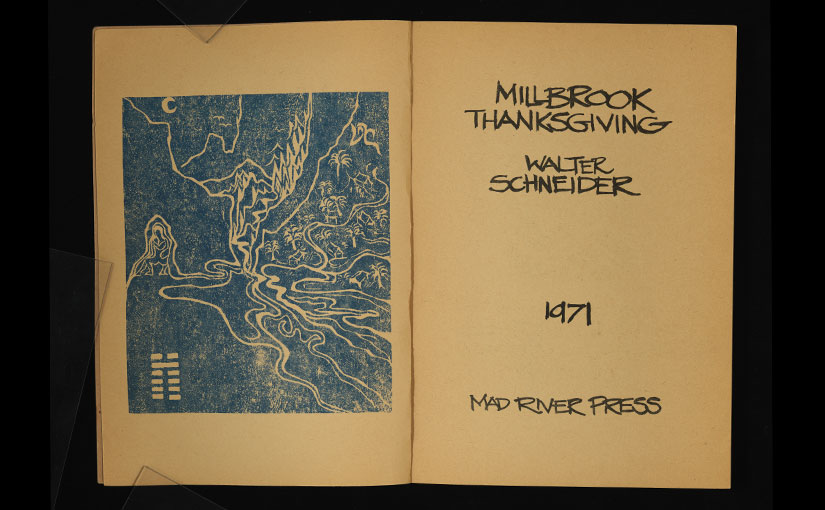

This Thanksgiving we’re highlighting a book of poetry and prose that is part of a group of avant-garde American literary works called the Small Press/Mimeograph Revolution, 1940-1970s collection. Millbrook Thanksgiving, by poet and writer Walter Schneider (1934-2015), is a panegyric to the psychedelic-fueled community Timothy Leary created in upstate Millbrook, New York from 1963 to 1967. A psychologist interested in the effects of synthetic drugs on human consciousness, Leary settled in Millbrook after being fired from Harvard University for using the substances he was studying (LSD was legal in the US at that time). In the wake of local police harassment that led to Leary’s repeated arrests for minor drug infractions, he moved to California where he crossed paths with Schneider, a PhD student at Berkeley.

Schneider’s spirited defense of Leary’s counter culturalism places the book’s content in the cultural vanguard of 1971. But so does the book’s production. Printed as a small run of just 3,000 copies, its design—from the soft cover, typography, and heavy paper, to its eclectic illustrations—signals the book’s origins outside of mainstream American publishing. Mad River Press, the small California-based operation that produced Millbrook Thanksgiving, specialized in experimental poetry and creations like Schneider’s. The press released very small runs of poetry chapbooks, which were short (40 pages or less), inexpensively constructed, soft-cover booklets. Some were published anonymously and with no identifying publication information, indicating that publisher and author rejected the authority of copyright law.

Mad River Press and its authors also placed important visual pieces in their publications. Millbrook Thanksgiving used the first photograph in Robert Frank’s The Americans (published 1958), an extended photo essay that captured Americans in real life. Beat writer Jack Kerouac, who introduced the 1959 edition, noted that “he [Frank] sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film.” His book of photographs remains an important visual text of post-war America. In a chapbook of poetry by Fred Glazer also published in 1971, Mad River Press included an image by the African American painter Louis Delsarte.

Mad River Press and its authors also placed important visual pieces in their publications. Millbrook Thanksgiving used the first photograph in Robert Frank’s The Americans (published 1958), an extended photo essay that captured Americans in real life. Beat writer Jack Kerouac, who introduced the 1959 edition, noted that “he [Frank] sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film.” His book of photographs remains an important visual text of post-war America. In a chapbook of poetry by Fred Glazer also published in 1971, Mad River Press included an image by the African American painter Louis Delsarte.

The library’s Small Press/Mimeograph Revolution, 1940-1970s collection holds more than 350 items. Some, like Millbrook Thanksgiving, were produced by small, experimental presses, while others were created by individuals or small collectives using relatively inexpensive copying technologies like the Ditto machine (remember the smell of those purple ink pages?) or the mimeograph. The collection is searchable in the library’s catalog.

RBSC will be closed during Notre Dame’s Thanksgiving Break (November 22-25, 2018). We wish you and yours a Happy Thanksgiving!

Thanksgiving 2015 RBSC post: Thanksgiving and football

Thanksgiving 2016 RBSC post: Thanksgiving Humor by Mark Twain

Thanksgiving 2017 RBSC post: Playing Indian, Playing White

A story for Halloween: “Johnson and Emily; or, The Faithful Ghost”

“It is always Christmas Eve, in a ghost story…”

“It is always Christmas Eve, in a ghost story…”

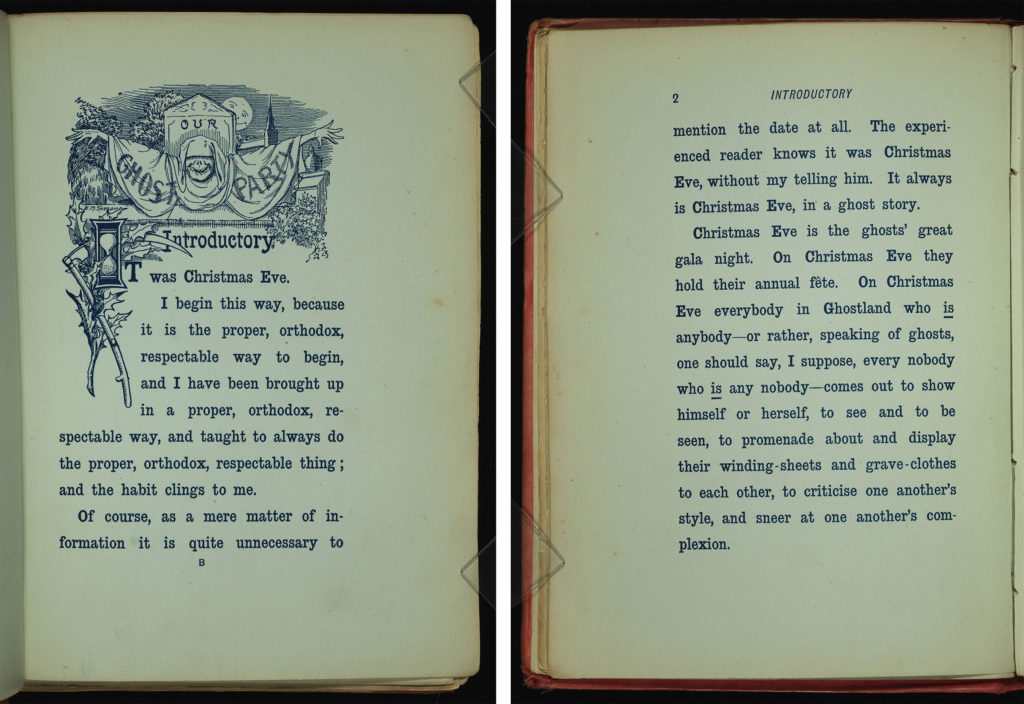

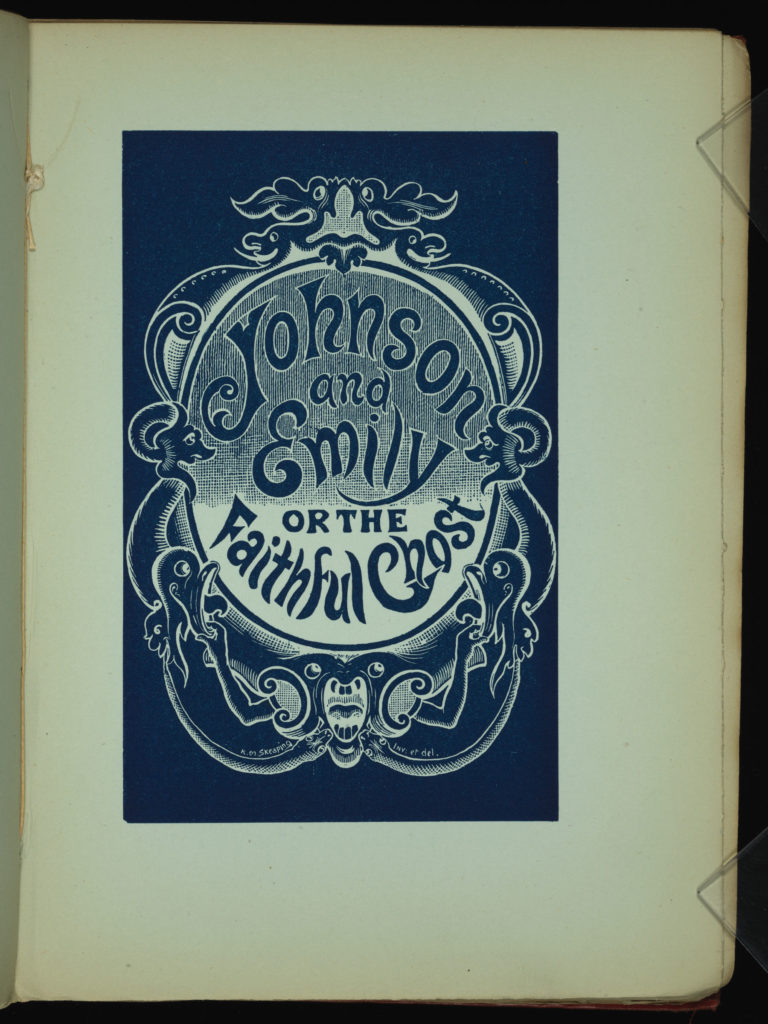

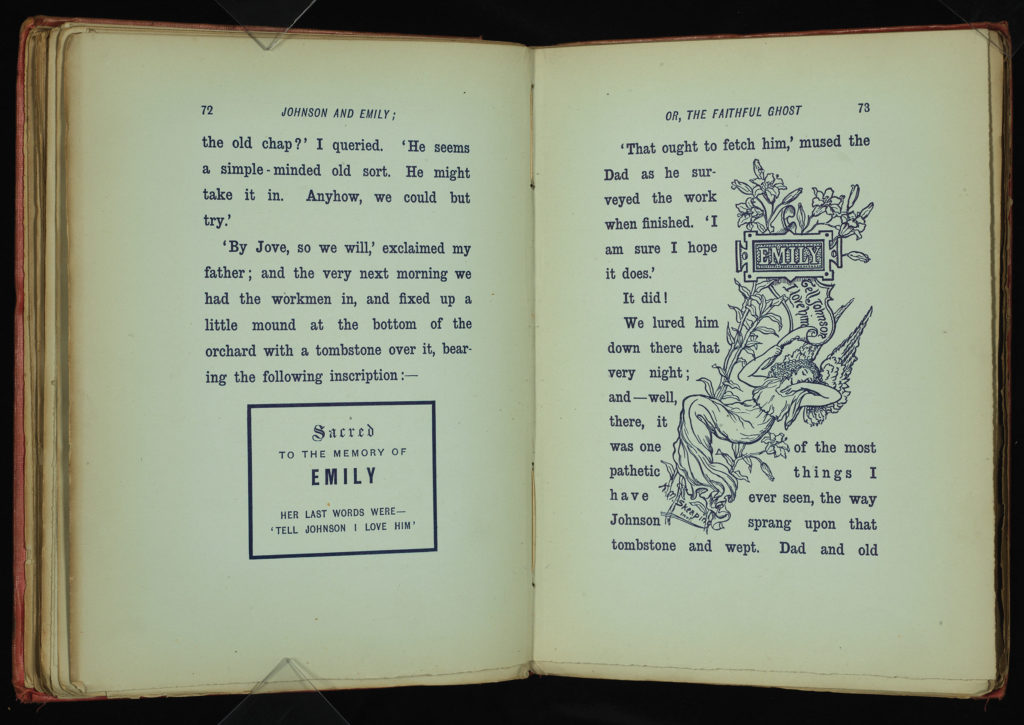

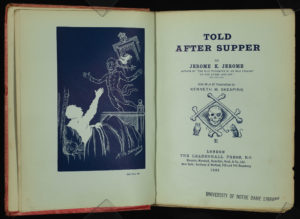

Told after Supper by Jerome K. Jerome is an anthology of short, humorous ghost stories. The copy in Special Collections, shown here, is the first edition, published 1891 by Leadenhall Press in London and illustrated “With 96 or 97 Illustrations” by Kenneth M. Skeaping.

The four primary stories, interspersed with shorter “Interludes,” are told by guests at a Christmas Eve dinner party hosted at the home of the narrator’s uncle. In 19th century England, it was typically not Halloween but Christmas Eve that was considered the time to tell spooky stories.

Jerome’s book follows in the tradition of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (first published in 1843) and other stories written or published by Dickens in the magazines he edited, Household Words and All the Year Round. Jerome’s stories are less frightening or moralizing, as the earlier Christmas ghosts tended to be, and more amusing.

And so, for this year’s Halloween post, we share for your amusement the first story from this volume, “Johnson and Emily; or, the Faithful Ghost”.

Happy Halloween to you and yours from all of us in Notre Dame’s Special Collections!

Halloween 2016 RBSC post: Ghosts in the Stacks

Halloween 2017 RBSC post: A spooky story for Halloween: The Goblin Spider

National Hispanic Heritage Month 2018

We join the Library of Congress and the National Endowment for the Humanities, National Gallery of Art, National Park Service, Smithsonian Institution, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and U.S. National Archives and Records Administration in celebrating National Hispanic Heritage Month.

Also in recognition of the anniversary of Hurricane María and Puerto Rico’s ongoing recovery struggle, this post highlights the island’s artistic heritage.

Puerto Rican Artists

by Erika Hosselkus, Curator, Latin American Collections

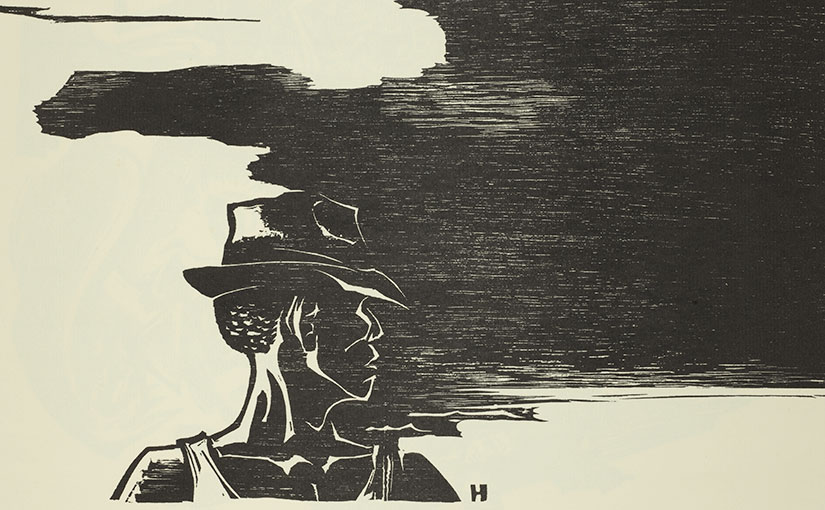

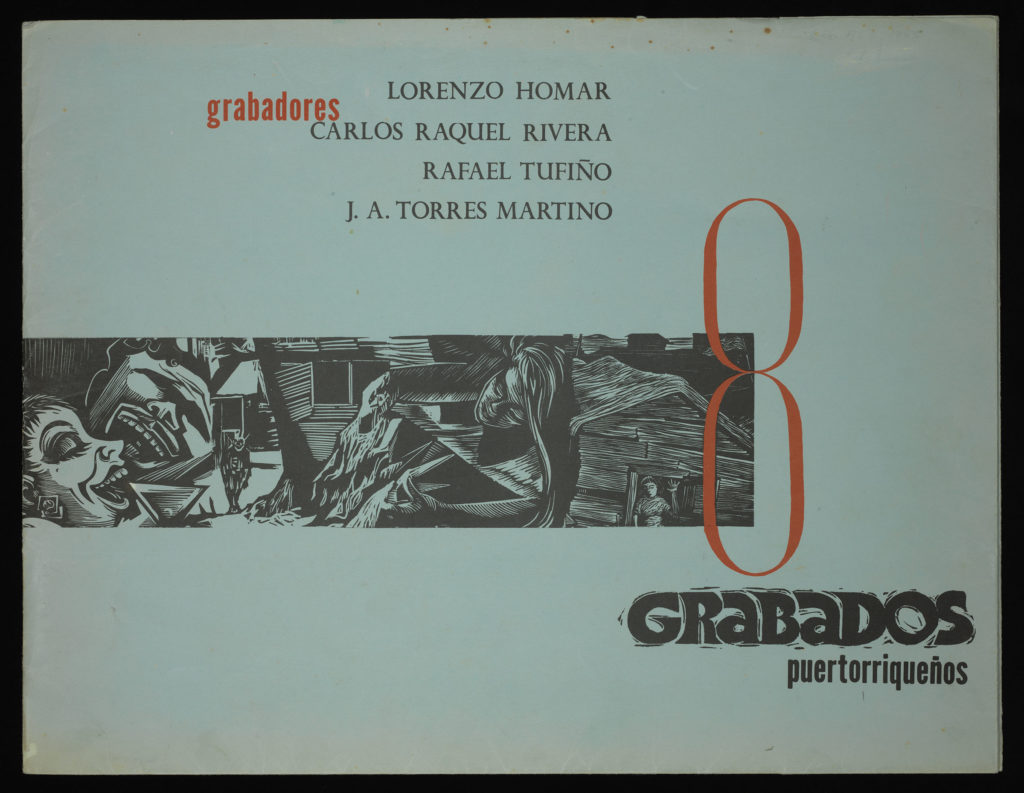

Puerto Rican artists Félix Rodríguez Báez, José A. Torres Martinó, Lorenzo Homar, and Rafael Tufiño (members of the Generation of ’50) formally established the Centro de Arte Puertorriqueño in 1950. This studio, art school, and gallery was influenced by the Taller de Gráfica Popular in Mexico and its mission of educating the public through art. At the same time, the member artists of the CAP used their work to express and assert a uniquely Puerto Rican identity.

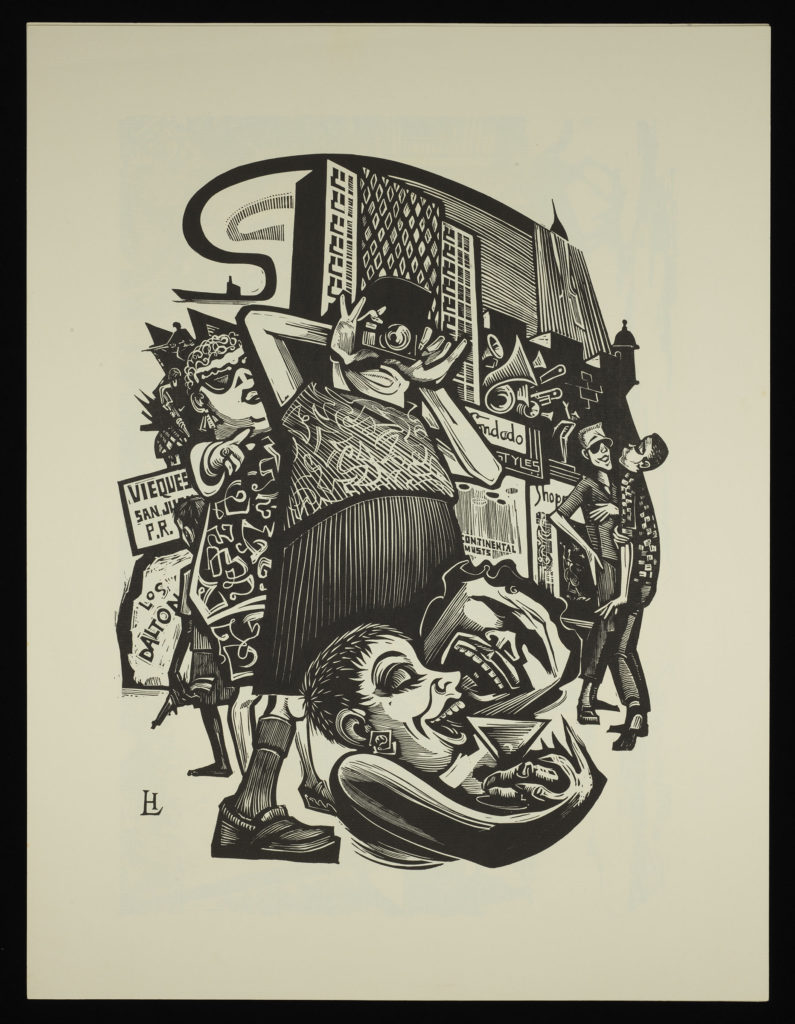

This portfolio of 8 prints, published in the late 1960s by the Centro de Artes Gráficas Nacionales, includes two works by each of four key members of the Generation of ’50, Lorenzo Homar, Carlos Raquel Rivera, Rafael Tufiño, and J.A. Torres Martino. The pieces are reproduced from original prints and were chosen to portray the development in aesthetic of each artist since 1951, when the CAP issued its first portfolio.

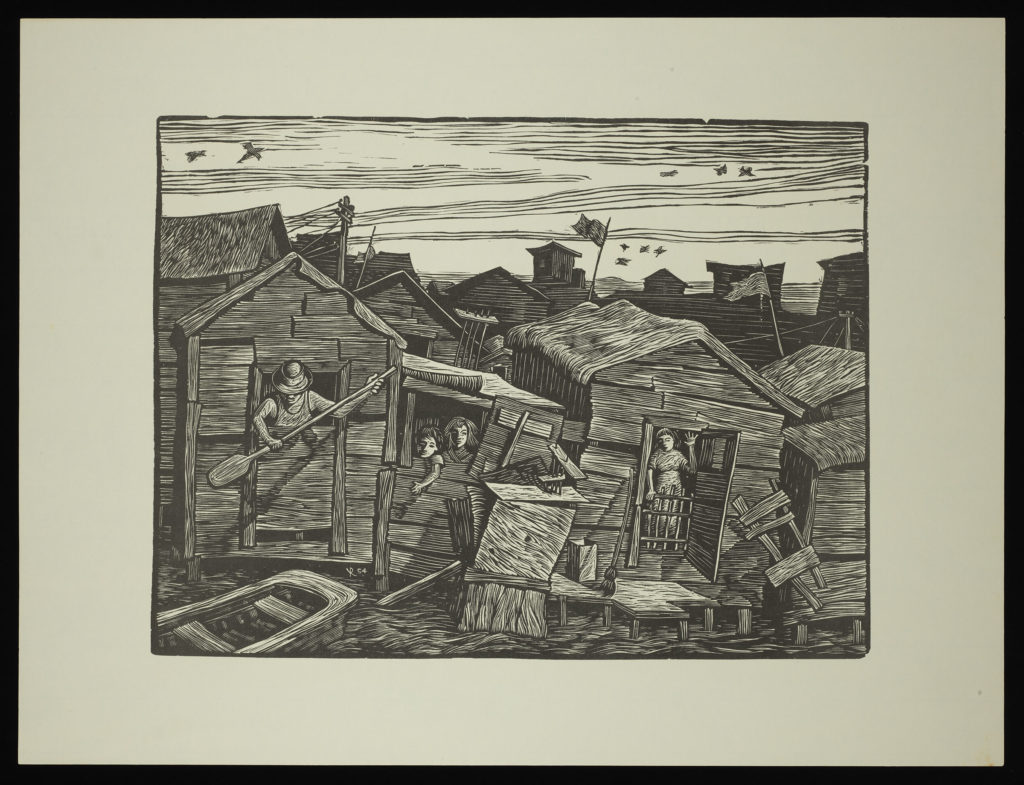

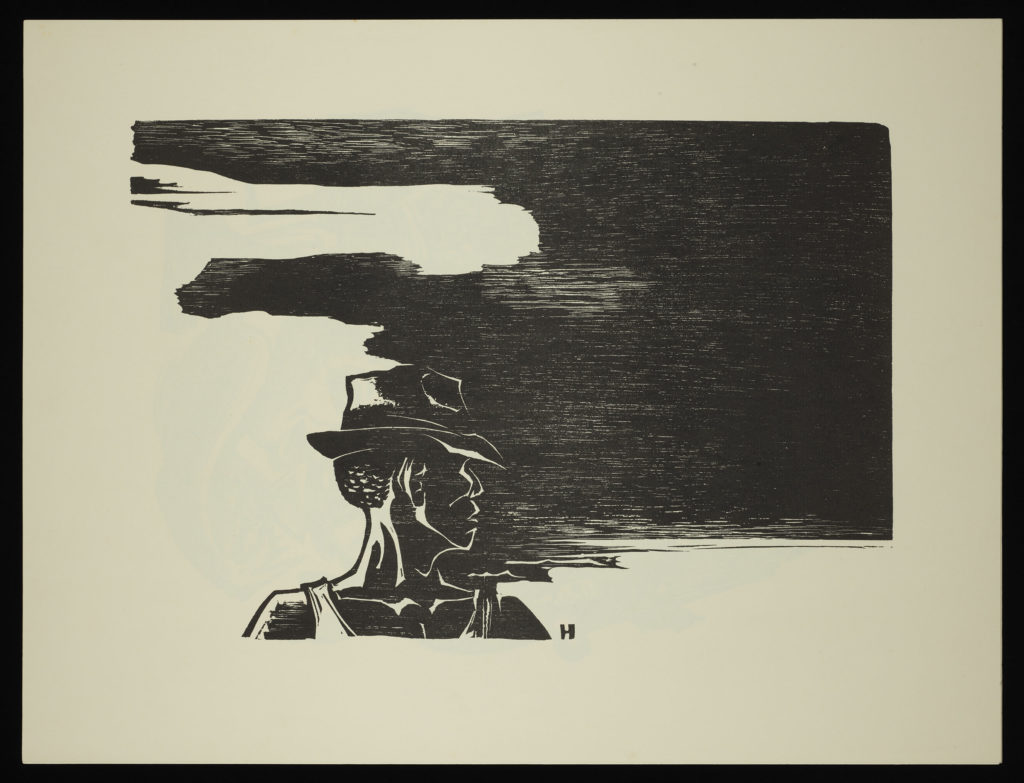

Carlos Raquel Rivera’s first print, “Marea Alta,” owes much to the influence of the Taller de Gráfica Popular in both the social commentary made through its content and in its style. His second print, “El Pegao,” reflects what had become Rivera’s signature style, driven by a strong black/white contrast.

The contrast between the two prints submitted by Lorenzo Homar is striking also. “La Tormenta” a depiction of a man peering over his shoulder at an oncoming storm is poetic and suggestive while “La Vitrina,” a critical depiction of tourism in Puerto Rico is bold and aggressive in style.

As a whole, this collection attests to the strength and evolution of print-making as an activist art form in mid-century Puerto Rico.

Francis Scott Key’s Poem Before It Became the Star Spangled Banner

by Rachel Bohlmann, American History Librarian

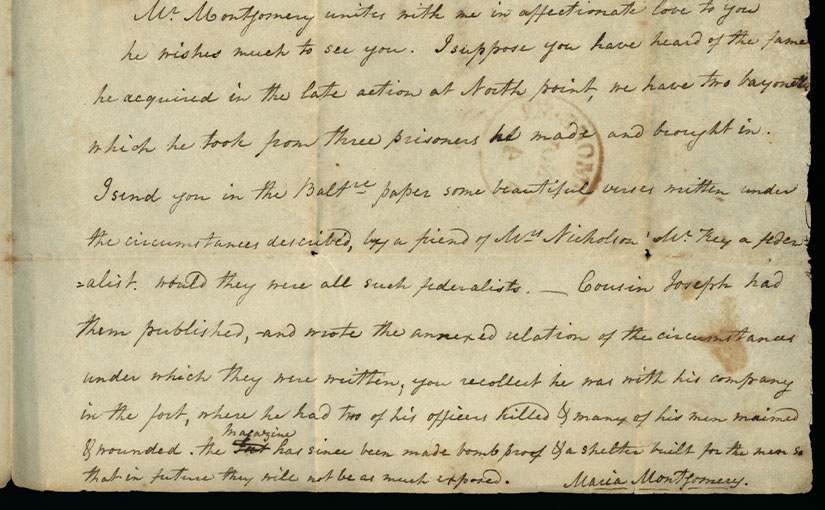

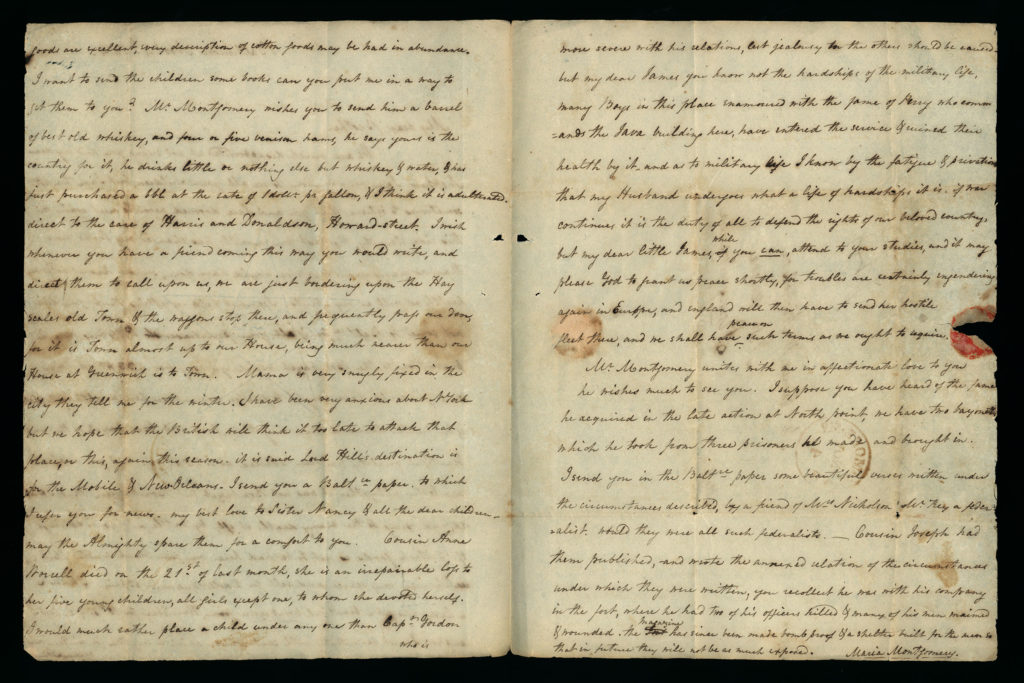

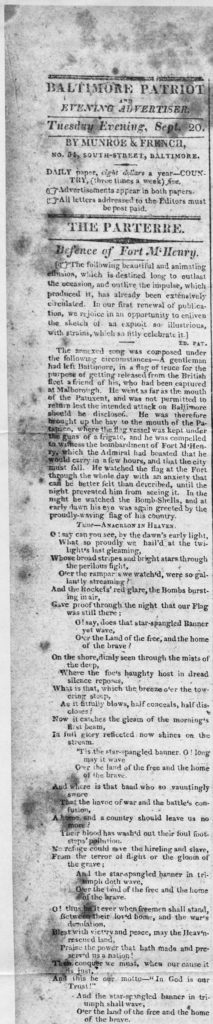

“Some Beautiful Verses Written under the Circumstances”

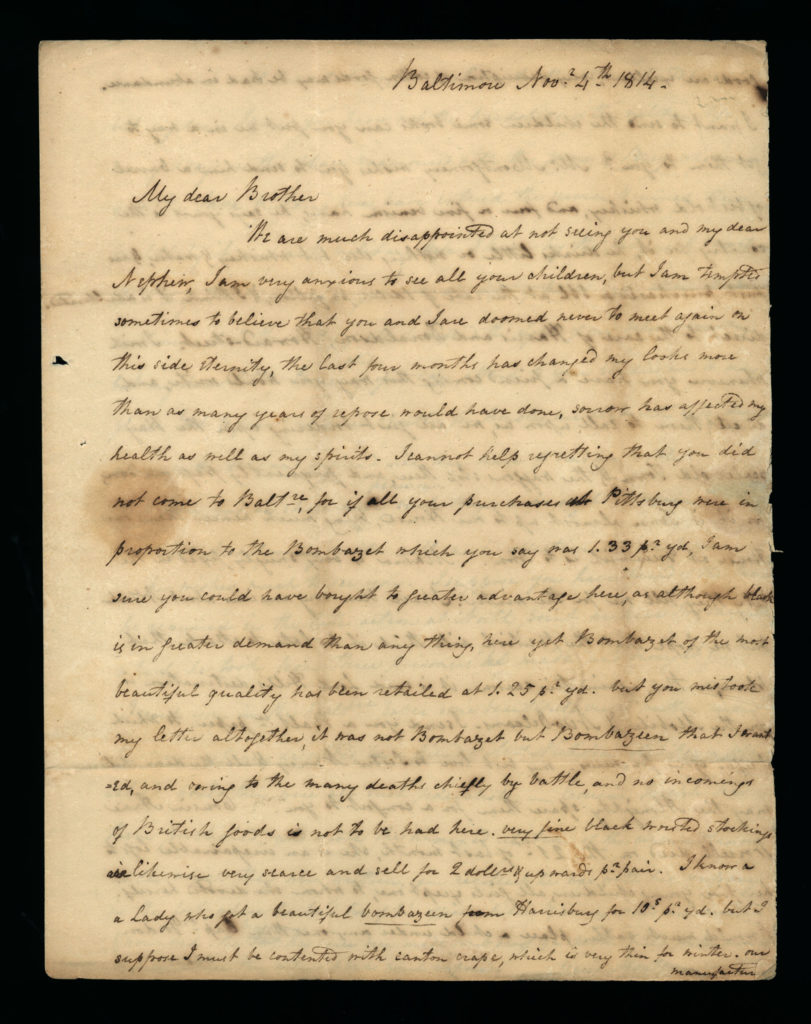

This was how Maria Nicholson Montgomery, a Baltimore resident and wife of the city’s future mayor, described Francis Scott Key’s poem, “Defence of Fort McHenry,” in a letter to her brother in November 1814. Fort McHenry was the US garrison in Baltimore harbor and the British military’s target on September 12-14, 1814, during the War of 1812. Key had been detained on a British vessel a few miles away from the city. At dawn on the 14th, after a long night of bombardment, he spied the American flag over the fort and quickly drafted four stanzas on the American victory, set to a popular English tune, “Anacreon of Heaven.”

This was how Maria Nicholson Montgomery, a Baltimore resident and wife of the city’s future mayor, described Francis Scott Key’s poem, “Defence of Fort McHenry,” in a letter to her brother in November 1814. Fort McHenry was the US garrison in Baltimore harbor and the British military’s target on September 12-14, 1814, during the War of 1812. Key had been detained on a British vessel a few miles away from the city. At dawn on the 14th, after a long night of bombardment, he spied the American flag over the fort and quickly drafted four stanzas on the American victory, set to a popular English tune, “Anacreon of Heaven.”

Key showed the poem to his brother-in-law (and Montgomery’s cousin) Joseph Nicholson, who had commanded a company of volunteers at the fort. He was enthusiastic and helped Key publish them quickly in a broadside on September 17, 1814. By October a Baltimore music store had begun selling copies as sheet music retitled as “The Star Spangled Banner.”

Montgomery’s letter is part of the James Witter Nicholson Family Letters (MSN/EA 5002) held in Rare Books and Special Collections. The correspondence reveals the everyday details of life as well as a family’s political and social ambitions during the early republic.

Special Collections will be closed on Wednesday for the holiday but will be open regular hours (9am-5pm) the rest of the week.

We wish you and yours a safe and happy Fourth of July!

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Memorial Day 2018

To honor all who died while serving in the United States Armed Forces.

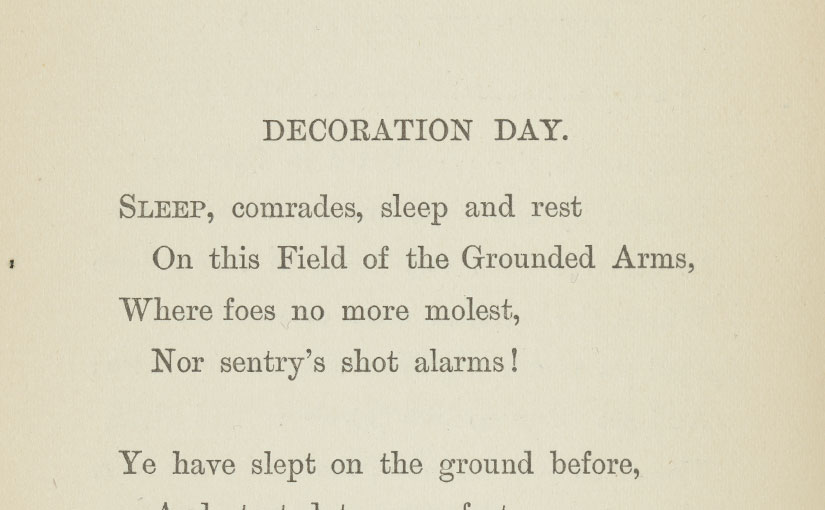

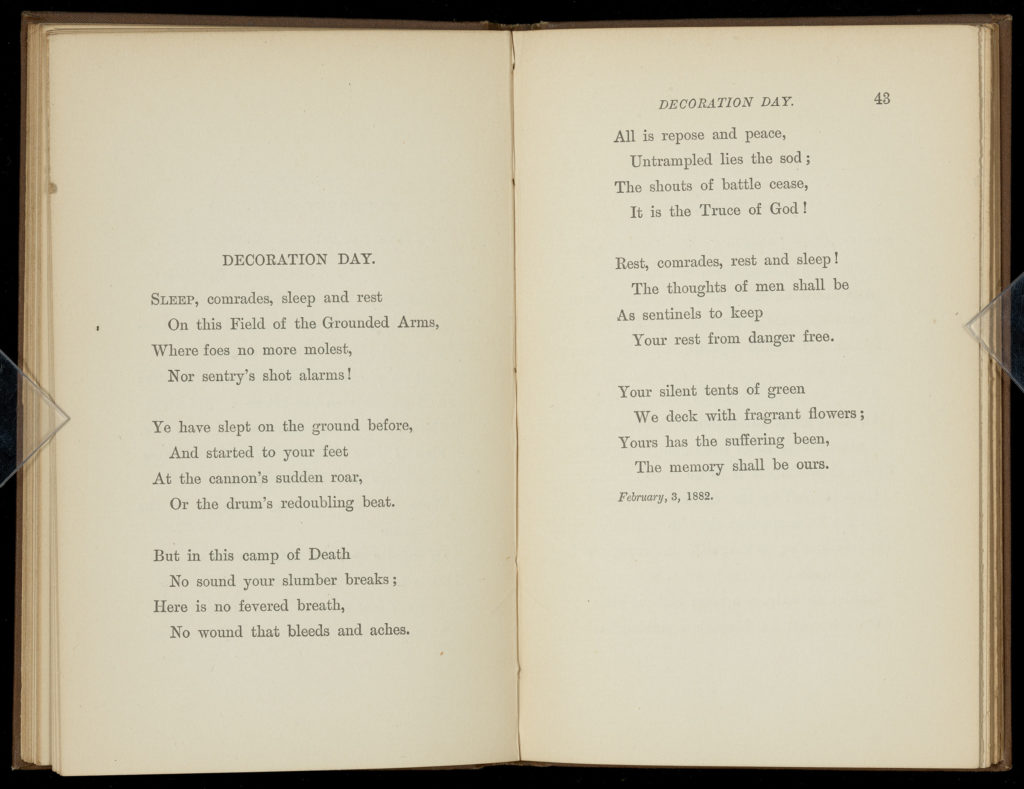

Originally, Memorial Day was celebrated as Decoration Day.

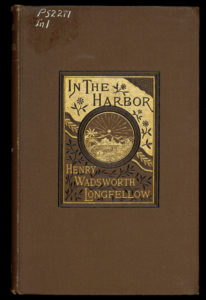

“Decoration Day,” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, was published posthumously—first in June 1882 in The Atlantic and later that same year in In the Harbor, a book containing previously unpublished poems. The poem “pays tribute to what was then a new form of civic observance: a day set aside to commemorate those who had perished in the Civil War by placing flags and flowers on soldiers’ graves, a custom that gradually gave rise to our modern Memorial Day honoring all who give their lives in military service.” (David Barber, The Atlantic, May 30, 2011)

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-82) was but five years old when he witnessed the War of 1812 devastate his hometown. This event had a long-lasting impact on him.

Wordsworth would go on to Bowdoin College, graduating along with Nathaniel Hawthorne in 1825 before traveling through Europe, where he gained mastery over seven languages. On his return to the US, he taught languages first at Bowdoin and later at Harvard, and also spent much time writing textbooks and essays on languages, particularly French, Italian, and Spanish. While at Harvard, Longfellow’s literary career took off. He travelled to Europe twice more before resigning from Harvard in 1854 to devote his full attention to writing.

Less than a decade later—in 1861—not only did his beloved wife, Fanny, die but the Civil War broke out and his son, fighting for the Union, was wounded. The invalid had to be escorted home by his father and brother. To cope with these tragedies, Longfellow immersed himself in his literary endeavors including a full translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy (completed in 1864). Against memories of the War of 1812, the Civil War, and the traumatic loss of a wife and the injury of a son, Longfellow continued to write. In some of his last pieces, including “Decoration Day,” one cannot help but notice Longfellow’s solemnity and poignancy.

Less than a decade later—in 1861—not only did his beloved wife, Fanny, die but the Civil War broke out and his son, fighting for the Union, was wounded. The invalid had to be escorted home by his father and brother. To cope with these tragedies, Longfellow immersed himself in his literary endeavors including a full translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy (completed in 1864). Against memories of the War of 1812, the Civil War, and the traumatic loss of a wife and the injury of a son, Longfellow continued to write. In some of his last pieces, including “Decoration Day,” one cannot help but notice Longfellow’s solemnity and poignancy.

During June and July the blog will shift to a summer posting schedule, with posts every other Monday rather than every week. We will resume weekly publication on August 13th.

An Easter Issue from Our Collections

The Game: An Occasional Magazine was first issued in 1914 by Eric Gill, Edward Johnston, and Hilary Pepler. This publication became the main forum for members of the Guild of St. Joseph and St. Dominic.

The Easter 1917 issue featured here is from the Eric Gill Collection. It contains Eric Gill’s woodblock prints, “The Resurrection” and “Paschal Lamb” accompanied by text from The Easter Sequence by Wipo (d. 1048).

Rare Books and Special Collections will be closed in observance of Good Friday on March 30. We will reopen at 9am on Monday, April 2, 2018.

Happy Easter to you and yours

from Rare Books and Special Collections

at the University of Notre Dame.

St. Patrick’s Day in America (1872)

by Aedín Ní Bhróithe Clements, Irish Studies Librarian

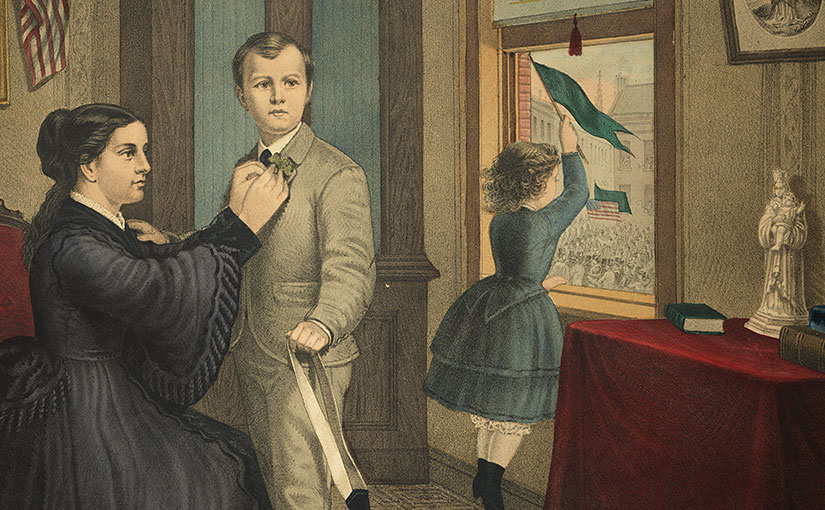

This lithograph was printed in Philadelphia at a time when the general impression of Irish immigrants was that of an impoverished people, unfavorably viewed by native-born Americans. Irish immigration to the U.S. in the 1830s and 1840s was becoming dominated by poor, unskilled rural Catholics, and in the decades following the Great Famine, American cities were inundated by waves of impoverished Irish peasants.

“St. Patrick’s Day in America. Commemorative of Ireland’s unswerving fidelity to her ancient religion and the devotion of her exiled children to the sacred principles of her freedom and redemption as a nation.” Washington: John Reid, 1872. Lithograph by Hunter and Duval. [i]

Hence, according to historian Kerby Miller, all Irish immigrants were viewed negatively, including those who arrived with education, skills, or capital. He states that “in the eyes of native-born Protestants, middle-class Irish Catholic immigrants were by religion and association not ‘good Americans’, but in the opinion of many of their own transplanted countrymen, they were not ‘good Irishmen’ either.” [ii]

Considering this attitude to Irish immigrants, then, the lithograph doubles as an effective piece of propaganda and a heartwarming picture of family life. The mother and children are respectably dressed, and the sewing machine suggests an industrious household. Symbols of Ireland include the statue of St. Patrick while the portrait on the wall, of an American soldier, suggests a relative, perhaps even the absent father, fought in the American Civil War.

The mother is pinning a shamrock on the boy’s lapel. The shamrock, emblematic of St. Patrick, is a popular symbol of Irish identity. The family is clearly preparing to take part in the celebration of their Irish identity, while at the same time the image proclaims American middle-class orderliness and industry.

To read about St. Patrick’s Day, see the following books in the Hesburgh Library:

Cronin, Mike and Daryl Adair. The Wearing of the Green: A History of St. Patrick’s Day. Routledge, 2002. Hesburgh Library GT 4995 .P3 C76 2002

Skinner, Jonathan and Dominic Bryan (eds.) Consuming St. Patrick’s Day. Cambridge Scholars, 2015.

Hesburgh Library GT 4995 .Pe S556 2015

Fogarty, William L. The Days We’ve Celebrated. St. Patrick’s Day in Savannah. Printcraft Press, 1980. GT 4995 .P3 F63.

Dupey, Ana María (ed.) San Patricio en Buenos Aires: Celebracionse y rituales en su dimensión narrativa. Buenos Aires: Editorial Dunken, 2006. GT 4995 .P3 S25 2006.

[i] To learn more about the lithographers of Philadelphia, see Erika Piola (ed.) Philadelphia on Stone: Commercial Lithography in Philadelphia 1828-1878, Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012.

[ii] Kerby A. Miller. Ireland and Irish America: Culture, Class, and Transatlantic Migration. Dublin: Field Day, 2008, p. 260.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Happy National Puzzle Day!

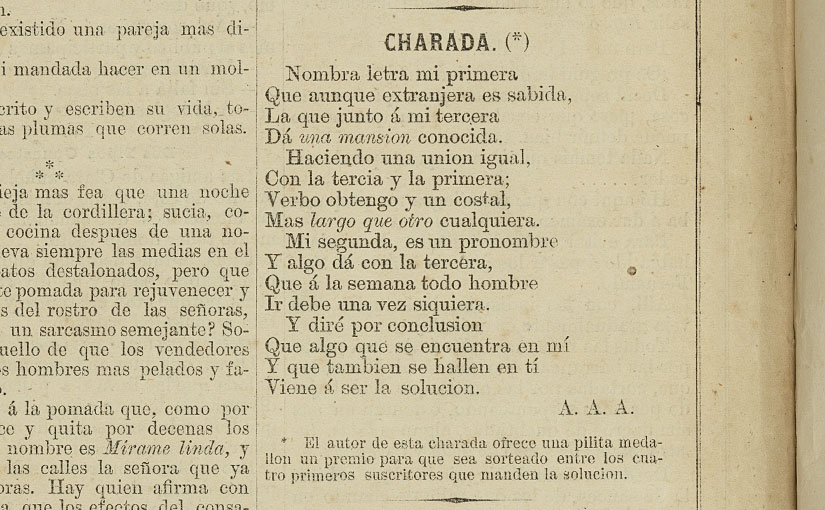

January 29 is National Puzzle Day, a day to appreciate puzzles of all sizes, shapes, and forms. This holiday was started in 2002 by Jodi Jill, a syndicated newspaper puzzle maker and professional quiz maker. In honor of the holiday, the curator of our next exhibit, “In a Civilized Nation: Newspapers, Magazines, and the Print Revolution in 19th-Century Peru,” shares a couple of puzzles from two of the serials that will be featured in the exhibit. The exhibit will open in early February.

by Erika Hosselkus, Curator, Latin American Collections

The periodicals of nineteenth-century Peru often featured puzzles, from riddles (charadas) to rebuses (geroglíficos).

The March 13, 1875 issue of La Alborada, a weekly magazine on literature, art, education, theater, and fashion, featuring the writing of Peruvian women, contains a word puzzle in the middle of the third column. Readers decoded riddles such as this one to discover a one-word or multi-word solution. In this case, the puzzle creator provides clues about the three syllables comprising the word camisa (shirt), her one-word solution.

A loose translation:

Although foreign, it is known

That when I join my first syllable to my third,

It results in a familiar mansion.

Creating a similar union

Between my third and my first syllables;

I obtain a verb and a “sack,”

“larger than” any other.

My second (syllable) is a pronoun

And it runs into my third,

Each week, every person

Should go (to this) at least once.

I will say, in conclusion

That something that you find on me

And that you find also on yourself

Will turn out to be the solution.

A.A.A.

The author of this puzzle offered up a prize to be given to one of the first four subscribers to submit a solution.

Solutions to the puzzle (Soluciones á la charada del núm. 22) appear in a later issue, shown below. Some answers, like the one sent in by Ubalda Plasencia, are written in verse, like the puzzle itself. As Ubalda points out, the syllables indicated by the puzzle are “ca” “mi” and “sa,” resulting in the word camisa, or “shirt.”

Word searches (laberintos) are also featured in Peruvian periodicals, as are rebuses, like the one found at the bottom of the page below from El Perú Ilustrado of June 16, 1888. The prize for decoding this puzzle was 200 packs of cigarettes. Fittingly, the sponsor of the puzzle was a tobacco vendor. In English, the solution to the puzzle (shown at the bottom of the last image) is: “If you know what is good, in terms of tobacco, I advise you to buy the brand «El Sol de Oro» from Oliva brothers.”