By Joyce Rivera González, Ph.D. Candidate, Department of Anthropology

It reeks to always walk with tense shoulders, shoved upwards

A knife hidden under my tongue

Rear wheel mirrors

— Karla Cristina

Sobre el hombre y otros sistemas de colapso

(La Impresora, 2020)

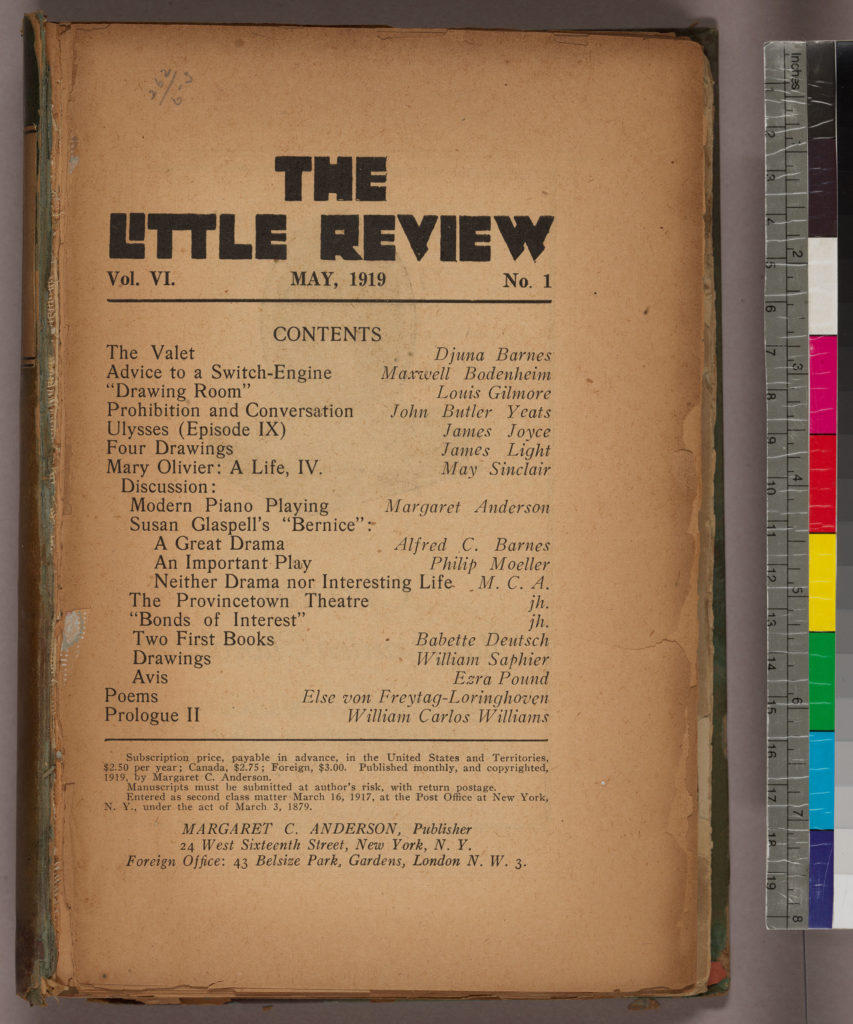

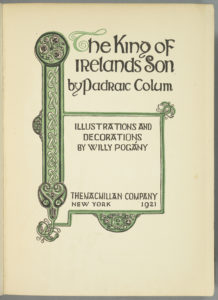

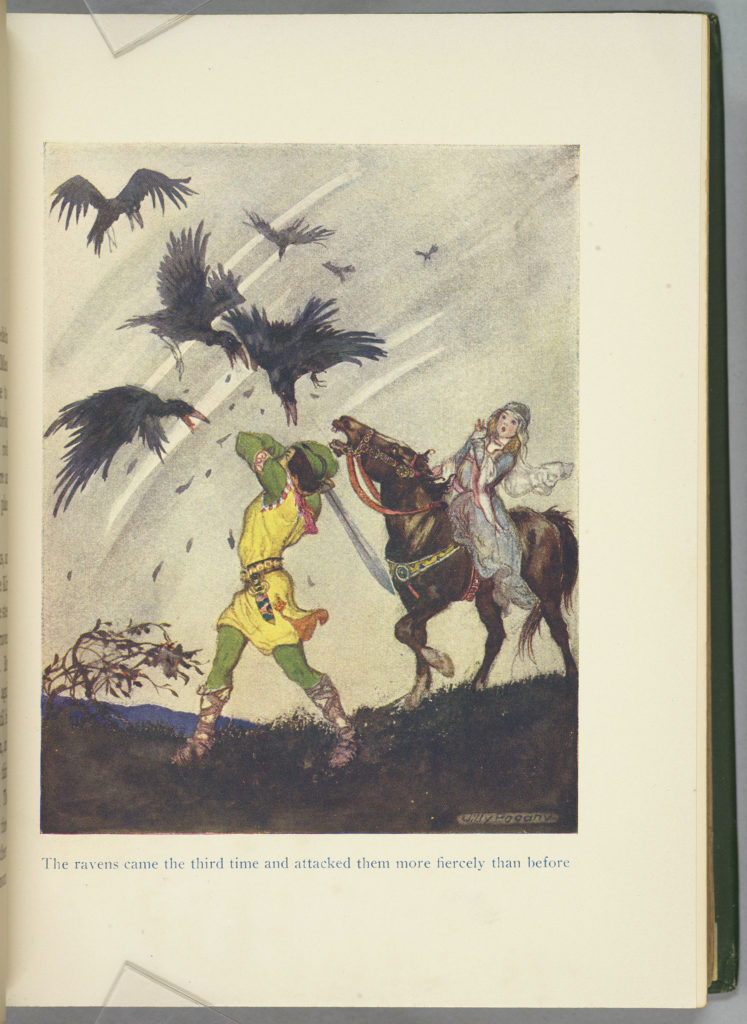

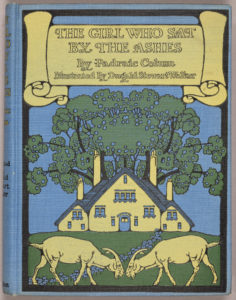

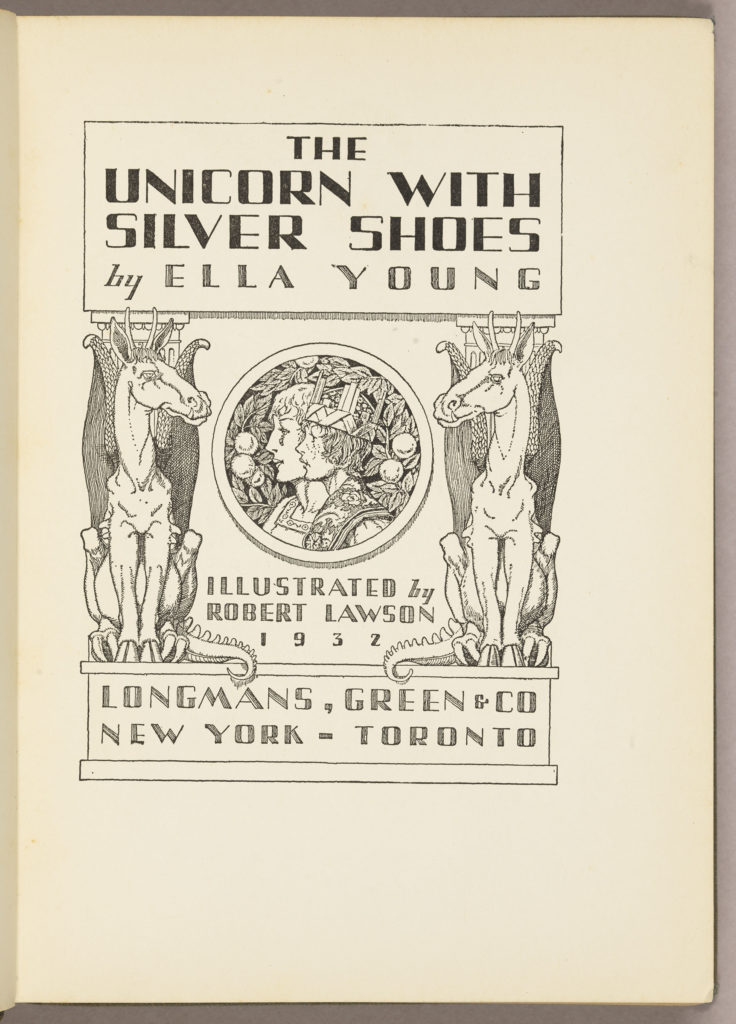

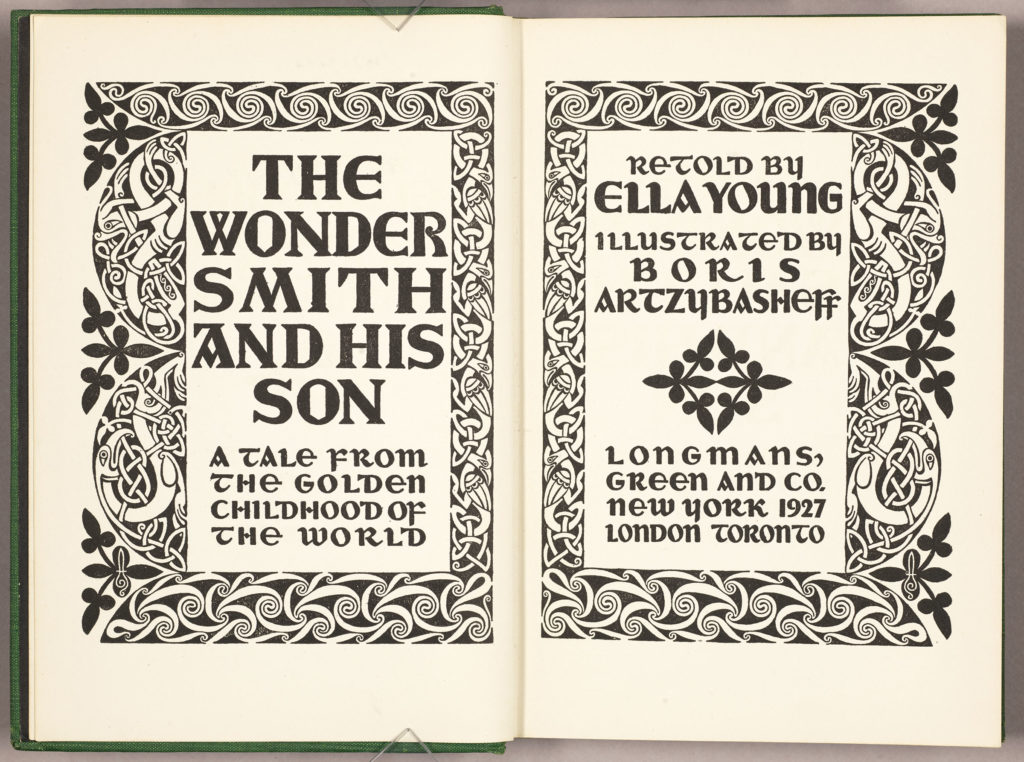

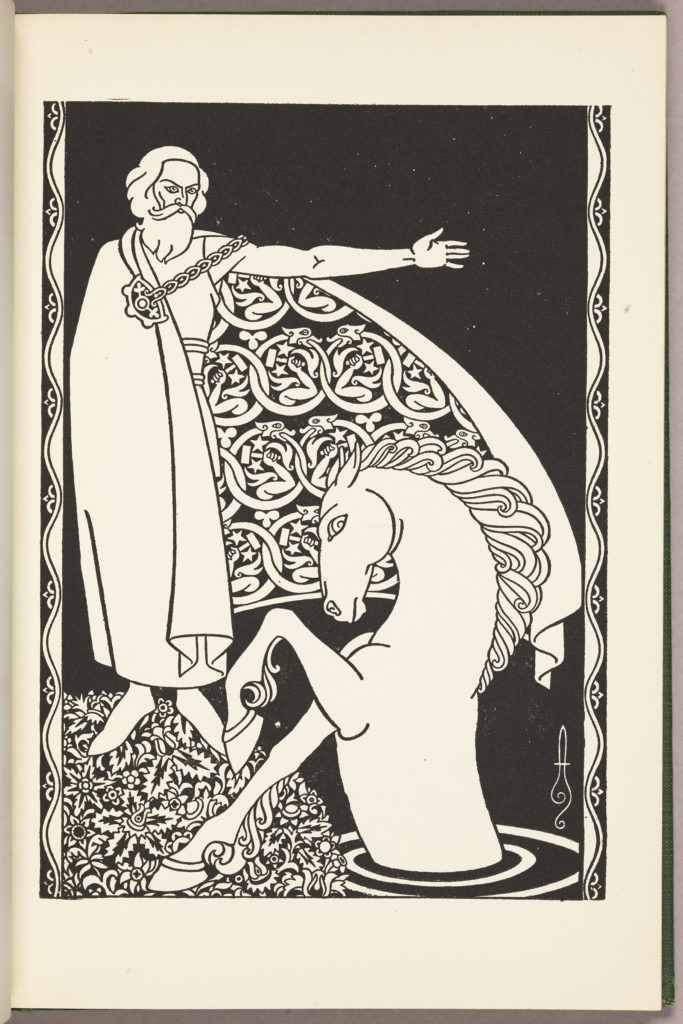

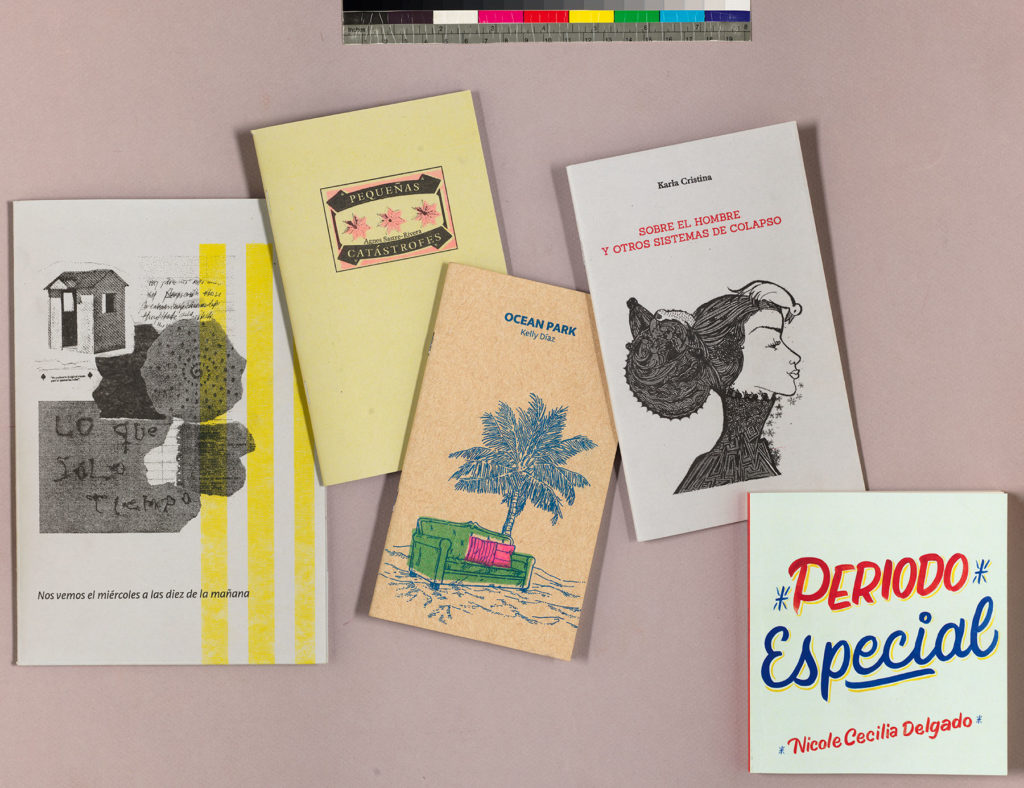

In this blog post, we showcase a collection of zines, chapbooks, and posters published by the independent, women-led Puerto Rican press La Impresora (“the printer,” in Spanish). This collection is one of the most recent acquisitions to augment Rare Books and Special Collections’ holdings of Hispanic Caribbean literature.

La Impresora is an experimental workshop headquartered in northwestern Puerto Rico. It is a small-scale risograph press, which combines the aesthetic and uniqueness of stencil and screen-printing with the expediency and convenience of digital copiers. Since the inception of risograph technology in 1940s Japan, this technology has allowed artists around the world to conveniently and inexpensively reproduce and disseminate their creations. In addition, La Impresora seeks to be more than just a printing press: as part of its vision, creators and artists are actively involved in the reproduction of their art in what the press’ founders call a book-making school, “a space to learn and share knowledge that is not formally taught in Puerto Rico, which is usually mediated or limited by the supply and demand of the publishing market.”

The selection currently held by Rare Books and Special Collections is composed of 62 items, a polyphonic kaleidoscope of form and lived experience. Much of this work captures—textually and visually—the lingering stasis that haunts a generation of Puerto Ricans. To differing degrees, the archipelago’s youth have experienced systems of limbo, collapse, and crisis. These predicaments arise from socio-natural disasters (and postponed recoveries), neocolonialism, corrupt and impotent local government, and crippling (largely illegal) public debt. The pieces created by this collective comment on and represent both the everyday and large-scale manifestations of the Puerto Rican crisis.

Authors include (from left to right) the La Práctica collective, Agnes Sastre-Rivera, Kelly Díaz, Karla Cristina, and Nicole Cecilia Delgado.

In addition to the pamphlet-sized zines and chapbooks, the collection includes a limited run of eight posters (11 x 17″) published by the collective, the majority of which were the result of a collaboration between the press and female Puerto Rican artists between 2019 and 2021.

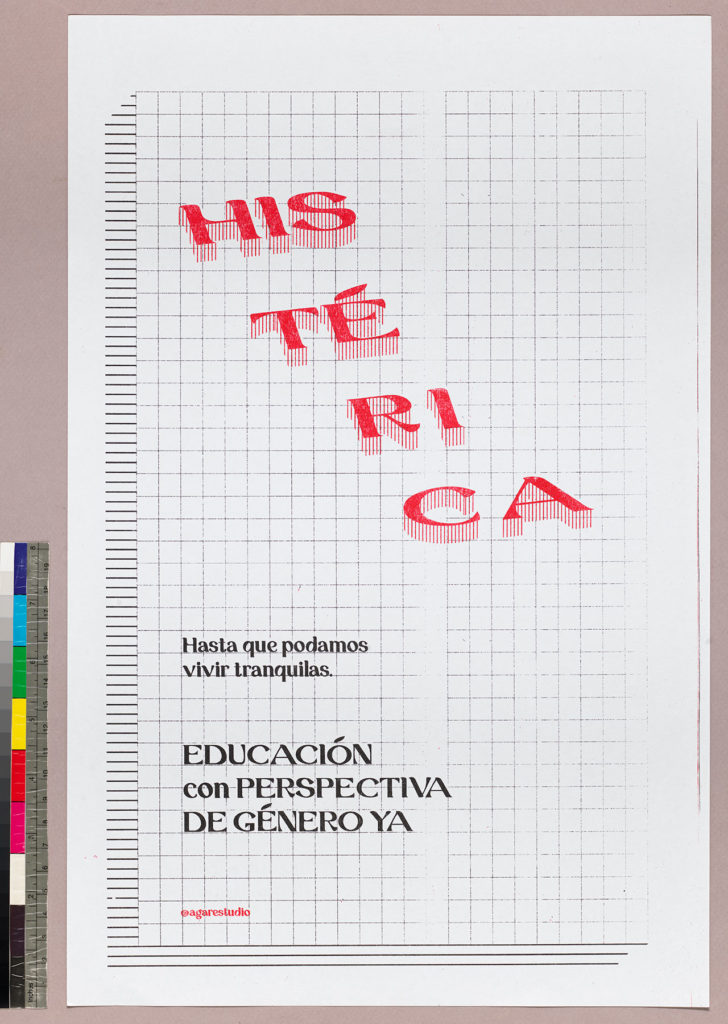

Some of the posters are the result of historical processes in the history of gender rights and relations in Puerto Rico. In “HISTÉRICA,” illustrator Adriana García centers the gendered attribute of “hysterical” in a minimally-illustrated piece. Written in red letters across a drawing grid, she embraces the gendered epithet and proclaims, in smaller, black font, to hysterically await a moment in which women “can live peacefully.” In slightly larger uppercase letters, she echoes contemporary demands for gender-perspective school curricula, an ongoing debate since at least 2008, split along partisan lines in the archipelago.

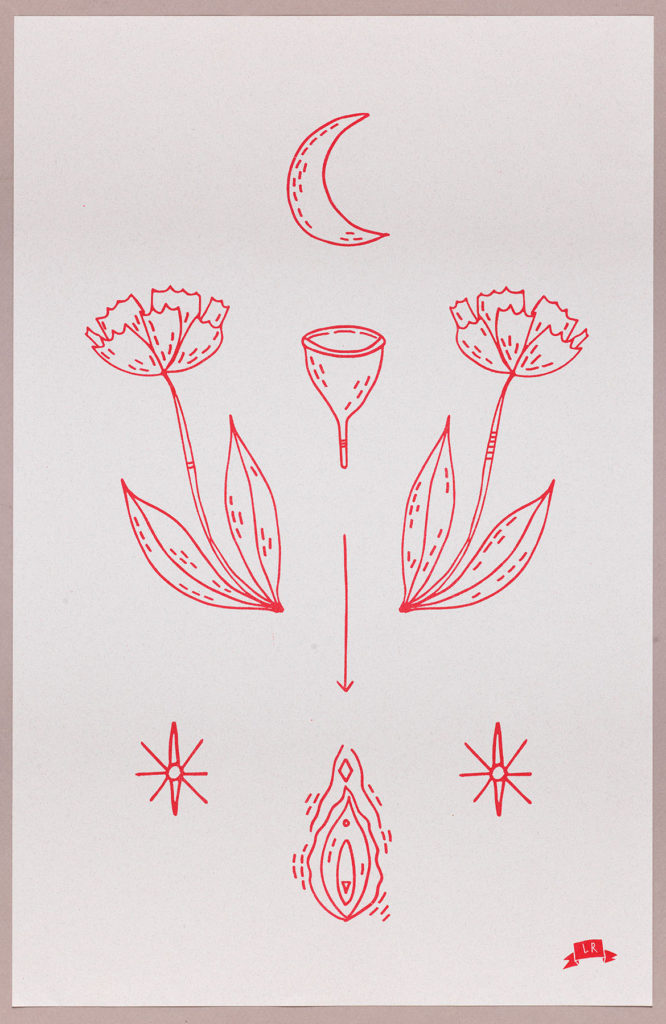

Part of the 2019 art exhibition “Oda a nuestra sangre” (trans. “ode to our blood”) held in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Lorraine Rodríguez’s print hopes to challenge societal taboos surrounding menstruation. In her piece, Rodríguez centers a minimally drawn menstrual cup, surrounded by blooming dandelions, a moon, and stars. In this landscape, menstruation is as natural as the blooms and celestial bodies that surround it. Moreover, the print seeks to desexualize and normalize female anatomy.

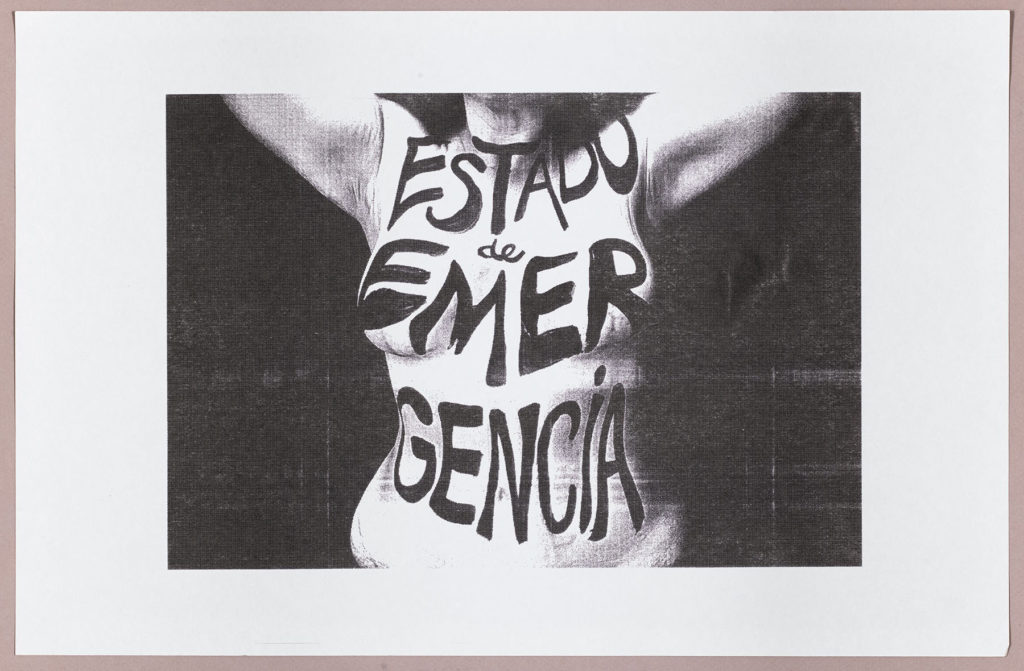

With the exception of Rodríguez’s piece (printed in 2019), the collection posters highlighted in this post were produced and distributed by La Impresora in 2021. This is far from a coincidence, as the year 2021 saw a record-breaking number of femicides and incidents of gender-based violence in Puerto Rico, averaging one a week. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) reports that Puerto Rico has the highest per capita rate of femicides against women over 14 years of age. These statistics include high-profile cases such as the murder of Keishla Rodríguez by rising boxer Felix Verdejo. In a way, many of the artworks in this collection emerge from the 2021 protests that demanded the enactment of a state of emergency by Governor Pedro Pierluisi in response to gender-based violence. Initially set to expire in June 2022, this state of emergency was recently extended: to this date, 24 women have been murdered in Puerto Rico, three times the number of 2021.

Echoing these demands, photographer Nina Méndez Martí highlights the black-and-white photograph of a woman’s torso. Hands in the air, the words “ESTADO DE EMERGENCIA” (trans. “State of emergency”) are emblazoned across her chest and abdomen in bold, black, uppercase letters.

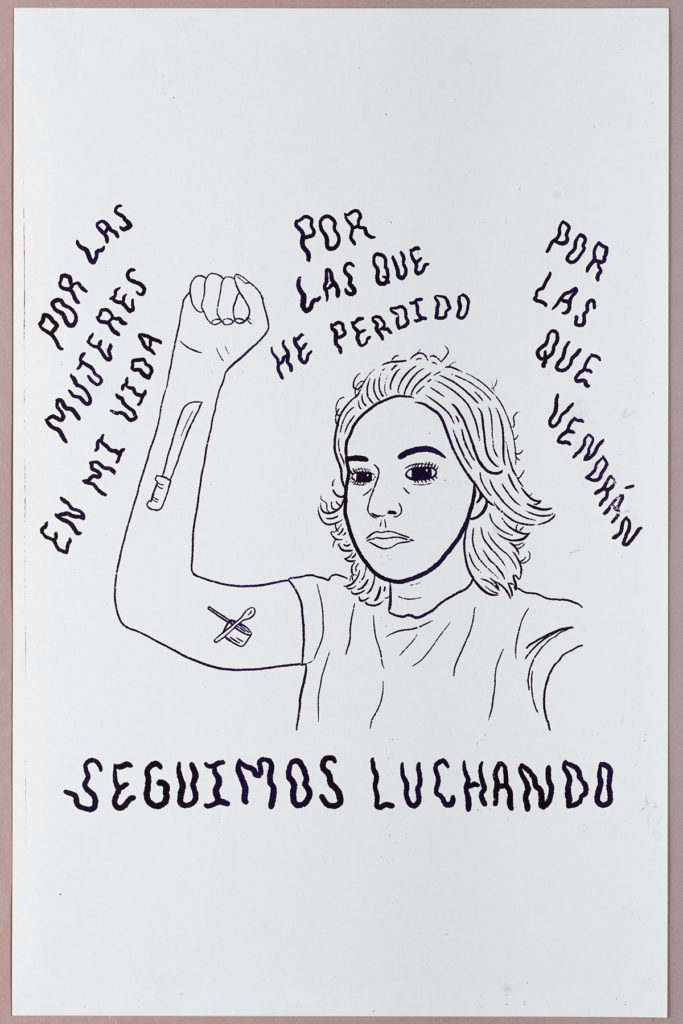

Lastly, Yvonne Santiago’s “Seguimos luchando,” depicts a woman drawn in purple lines, her right fist raised in the air. The color purple has a long and important history in feminist activism, from its association to women’s suffrage to Alice Walker’s famous analogy, “womanism is to feminism as purple is to lavender.” The woman depicted by Santiago has two tattoos: a pot (cacerola) with a cooking spoon on her tricep and a machete on her forearm. Both the cacerola and the machete are important symbols of resistance, especially in Puerto Rico.

The pot refers to the cacerolazo, a protest tradition which consists of banging pots cacophonously as a way of amplifying anger and dissatisfaction amid protests. In Puerto Rico, cacerolazos became a popular protest form during the Verano del 2019 protests, which called for the resignation of former governor Ricardo Rosselló.

The machete symbolizes pro-independence struggle and political nationalism on the island, most commonly associated with 20th-century armed pro-independence militancy, primarily with the Boricua Popular Army, known as Los Macheteros (trans. “Machete wielders”), and the Armed Forces of National Liberation (FALN). However, the machete, as a political symbol, dates to the original Revolutionary Anthem of Puerto Rico, written in 1868 by Lola Rodríguez de Tió. The hymn’s lyrics were deemed too controversial and revolutionary and were subsequently changed for a less political version in 1902.

Nosotros queremos la libertad

Y nuestros machetes nos la dará

We want Freedom

And freedom, our machetes will grant us

Yvonne Santiago’s piece chants its own hymn of subversion and defiance, lest we forget.

For the women in my life

For the ones I have lost

For the ones to come

We will keep fighting

Additional Resources

Spanish

Adriana Díaz Tirado & Alejandra Lara Infante, “Ni una más: las familias de las víctimas de feminicidios reclaman reparación y justicia,” Todas, November 22, 2021. URL: https://www.todaspr.com/ni-una-mas-las-familias-de-las-victimas-de-feminicidios-reclaman-reparacion-y-justicia/ (accessed Jun 23, 2022).

Cristina del Mar Quiles, “Sin fiscalización los programas de desvío para agresores por Ley 54,” Centro de Periodismo Investigativo, Jul 15, 2021. URL: https://periodismoinvestigativo.com/2021/07/fiscalizacion-programas-desvio-agresores-ley-54/ (accessed Jun 24, 2022).

Elithet Silva-Martinez & Jenice Vazquez Pagán, “El abuso económico y la violencia de género en las relaciones de pareja en el contexto puertorriqueño,” Prospectiva, 28 (2019): https://doi.org/10.25100/prts.v0i28.7264

María de los Milagros Colón Cruz, “Más agresores asesinan a sus parejas con un arma de fuego que mediante otras formas letales,” Centro de Periodismo Investigativo, Jun 9, 2022. URL: https://periodismoinvestigativo.com/2022/06/mas-agresores-asesinan-a-sus-parejas-con-un-arma-de-fuego-que-mediante-otras-formas-letales/ (accessed Jun 24, 2022).

Observatorio de Equidad de Género en Puerto Rico, “Feminicidios,” OEGPR website, May 12, 2022. URL: https://observatoriopr.org/feminicidios (accessed Jun 24, 2022).

Patricia Velez & Alvin Báez, “El dolor de los que se quedan: El calvario silencioso de los feminicidios en Puerto Rico,” Univisión Noticias, Jun 16, 2021. URL: https://www.univision.com/especiales/noticias/2021/feminicidios-violencia-genero-puerto-rico-calvario-silencioso/index.html (accessed Jun 23, 2022).

Redacción BBC, “Feminicidio en Puerto Rico: 4 claves para entender qué llevó a la isla a declarar un estado de emergencia por violencia de género,” BBC News Mundo, Jan 27, 2021. URL: https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-55820829 (accessed Jun 23, 2022).

English

ACLU, “Failure to Police Crimes of Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault in Puerto Rico,” ACLU website, n.d. URL: https://www.aclu.org/other/failure-police-crimes-domestic-violence-and-sexual-assault-puerto-rico (accessed Jun 23, 2022).

Aileen Brown, “Dozens of murdered women are missing from Puerto Rican police records, new report finds,” The Intercept, Nov 16, 2019. URL: https://theintercept.com/2019/11/16/puerto-rico-murders-femicide-police/ (accessed Jun 24, 2022).

Brittany Valentine, “Puerto Rico courts face down the greater issue of gender violence on the island,” Al Día, Aug 16, 2021. URL: https://aldianews.com/politics/policy/femicides-puerto-rico-0 (accessed Jun 24, 2022).

Carli Pierson, “She just wanted to be safe. Her femicide started a movement in Puerto Rico,” USA Today, Mar 13, 2021. URL: https://www.usatoday.com/in-depth/opinion/2022/03/13/angie-noemi-gonzalez-santos-puerto-rico-usa-today-women-of-the-year/6795005001/ (accessed Jun 24, 2022).

Cristina Corujo & Penélope López, “Puerto Rican families devastated by gender-based killings remain concerned about government’s approach to crisis,” ABC News, May 26, 2021. URL: https://abcnews.go.com/US/puerto-rican-families-devastated-gender-based-killings-remain/story?id=77739523 (accessed Jun 24, 2022).

Cristina del Mar Quiles, “The children whose mothers were taken away by machismo,” Centro de Periodismo Investigativo, Dec 16, 2021. URL: https://bit.ly/3xNHd0Y (accessed Jun 24, 2022).

Denise Oliver Velez, “The ‘other epidemic’ in Puerto Rico: Femicide and gendered violence,” Daily Kos, Jan 28, 2021. URL: https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2021/1/28/2012301/-The-other-epidemic-in-Puerto-Rico-is-femicide-and-gendered-violence (accessed Jun 24, 2022).

Jhoni Jackson, “Hundreds Take to the Streets of Puerto Rico to Protest Two Femicides,” Remezcla, May 3, 2021. URL: https://remezcla.com/culture/hundreds-take-streets-puerto-rico-protest-two-femicides/ (accessed Jun 24, 2022).

Lillian Perlmutter, “Deadly Violence Against Women in Puerto Rico is Surging During Lockdown,” VICE, Dec 8, 2020. URL: https://www.vice.com/en/article/qjpj5d/deadly-violence-against-women-in-puerto-rico-is-surging-during-lockdown (accessed Jun 24, 2022).

Nicole Acevedo. “Puerto Rico’s new tipping point: Horrific femicides reignite fight against gender violence,” NBC News, May 16, 2021. URL: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/puerto-rico-s-new-tipping-point-horrific-femicides-reignite-fight-n1267354 (accessed Jun 23, 2022).

Raquel Reichard, “Feminicide in Puerto Rico: A History of Violence and Resistance,” Hip Latina, Nov 30, 2020. URL: https://hiplatina.com/femicide-puerto-rico-protest-violence/ (accessed Jun 23, 2022).