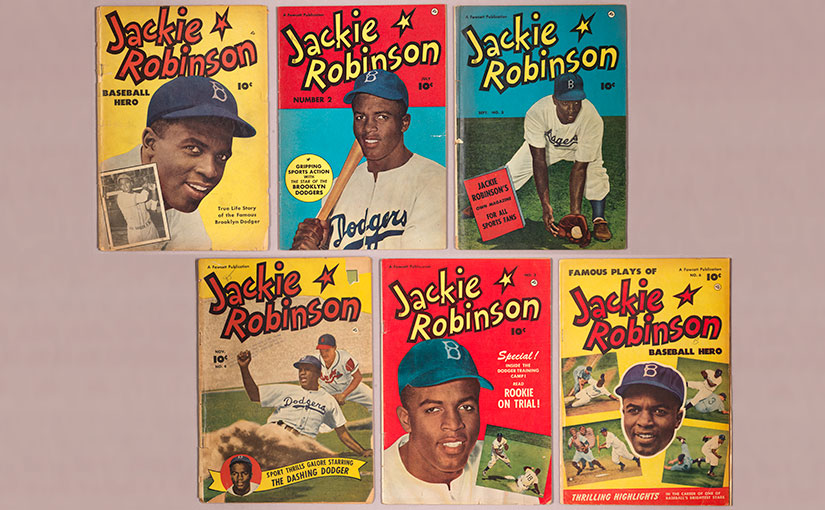

Jackie Robinson and Comic Book Baseball Heroes, 1949-1952

by Greg Bond, Sports Archivist and Curator, Joyce Sports Research Collection

“And now…. Jackie Robinson’s life in a comics magazine!!!”

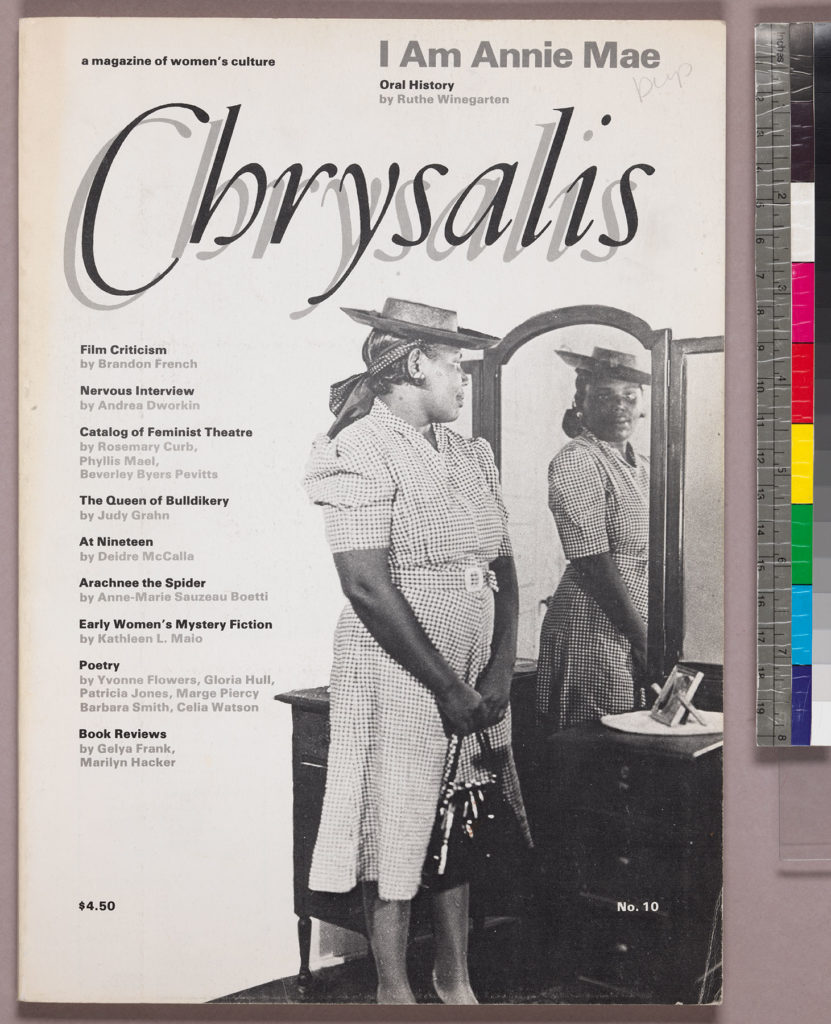

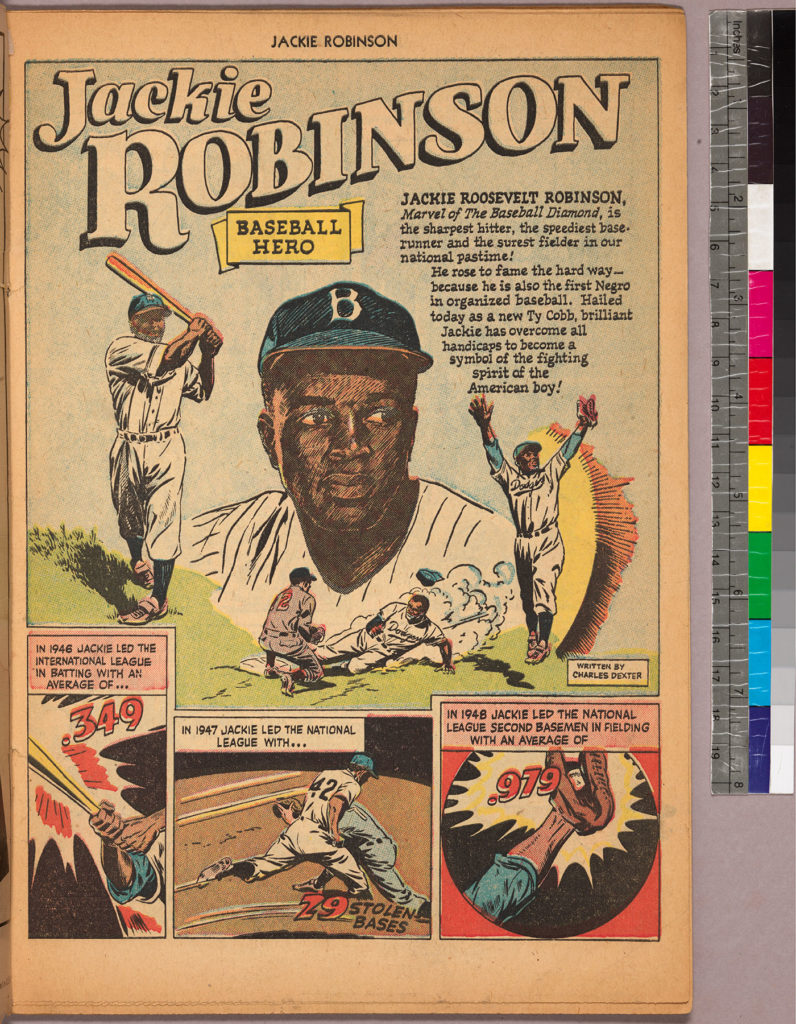

The Atlanta Daily World, a leading national African American newspaper, excitedly informed readers of its September 23, 1949, issue about a new Jackie Robinson comic book. “So great is the aura of stardom surrounding this greatest of Negro athletes,” the World explained, “that a special magazine bearing his name is being released.” Published by Fawcett Publications, the 32-page comic book titled, Jackie Robinson: Baseball Hero, related the life story of the Brooklyn Dodgers star.

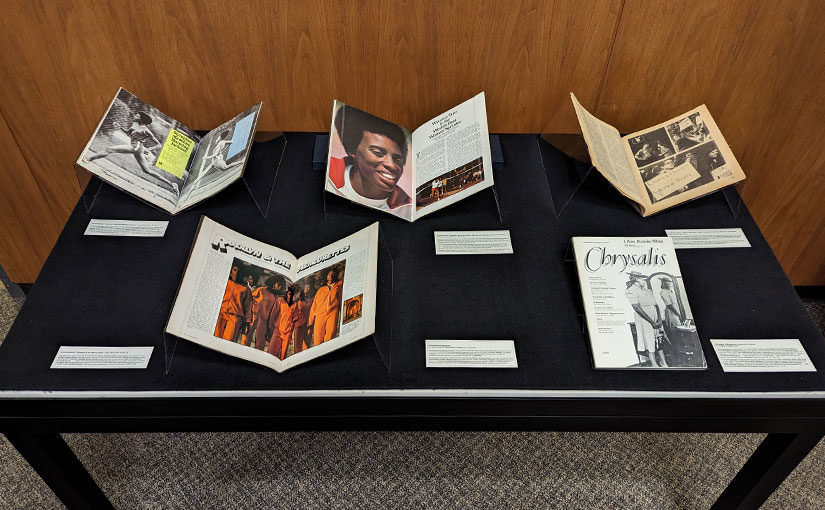

Fawcett, best known for creating the character Captain Marvel in the 1930s, published popular comic books for a national audience and teamed on the project with Robinson, the first acknowledged African American to play major league baseball in the twentieth century. Jackie Robinson: Baseball Hero proved to be a hit, and Fawcett followed up with five more titles about Robinson over the next three years and also collaborated with other early African American major leaguers like Larry Doby, Roy Campanella, and Don Newcombe on comic books about their lives.

These Fawcett publications, recently acquired by the Joyce Sports Research Collection, are among the earliest American comic books to feature positive, non-stereotypical, and non-demeaning portrayals of African American characters. They were also some of the earliest comic books from a mainstream publisher targeted to a national audience that featured African Americans as main characters.

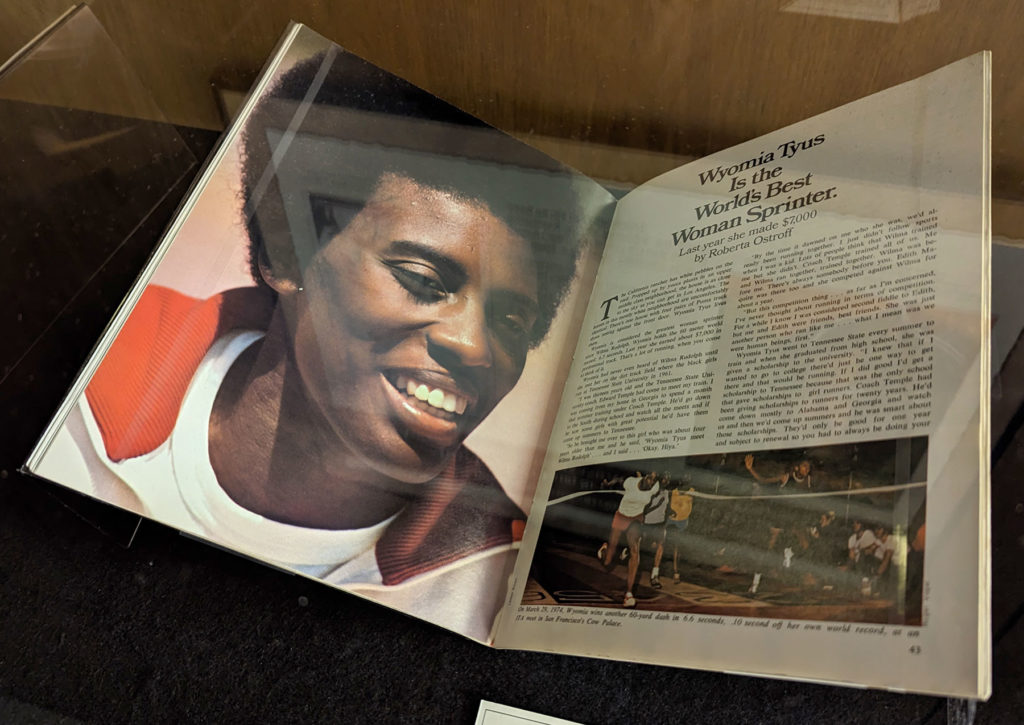

Jackie Robinson: Baseball Hero told Robinson’s biography from his youth in Pasadena to his career as a multi-sport athlete at UCLA to his early years in organized baseball—first at Triple A Montreal and then with the Brooklyn Dodgers. In its opening pages, the comic book proclaimed that “Jackie has overcome all handicaps to become a symbol of the fighting spirit of the American boy!”

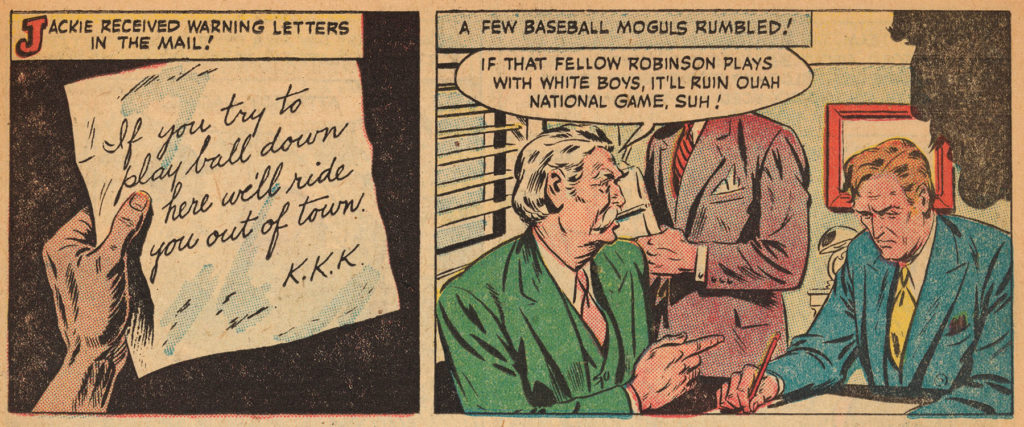

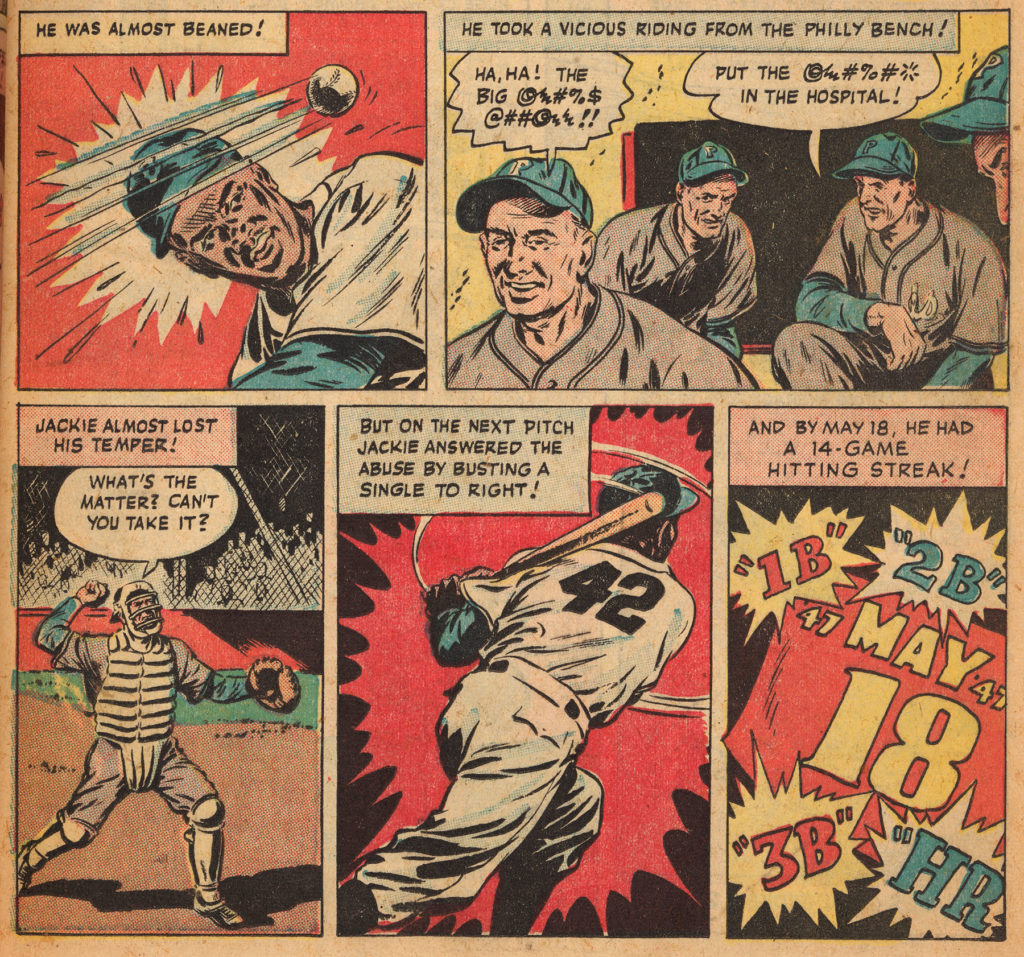

The comic book did not shy away from depicting the troubles Robinson faced in breaking major league baseball’s color line. The book illustrated, for example, the threats he received from the Klu Klux Klan, the opposition to integration from some major league owners, and the harassment he experienced on the field from other teams.

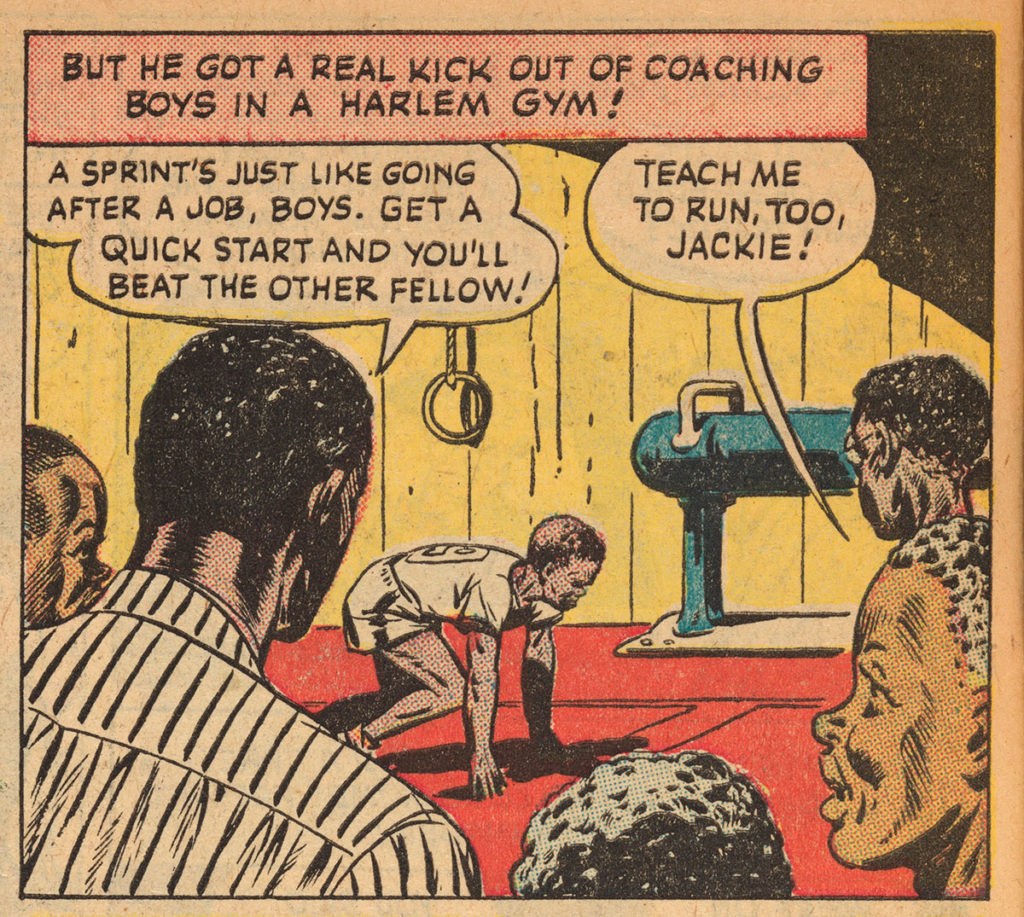

The book graphically detailed Robinson’s many successes on the ballfield, but it also highlighted Robinson’s awareness of his importance as a role model, particularly for African American children.

In one scene, for example, after he was scouted by the Dodgers, Robinson witnessed a group of African American boys playing in an alley and thought to himself, “If I ever play in the Majors, I’ll give kids like this some hope of making good.” The book also illustrated his work coaching children at a gym in Harlem.

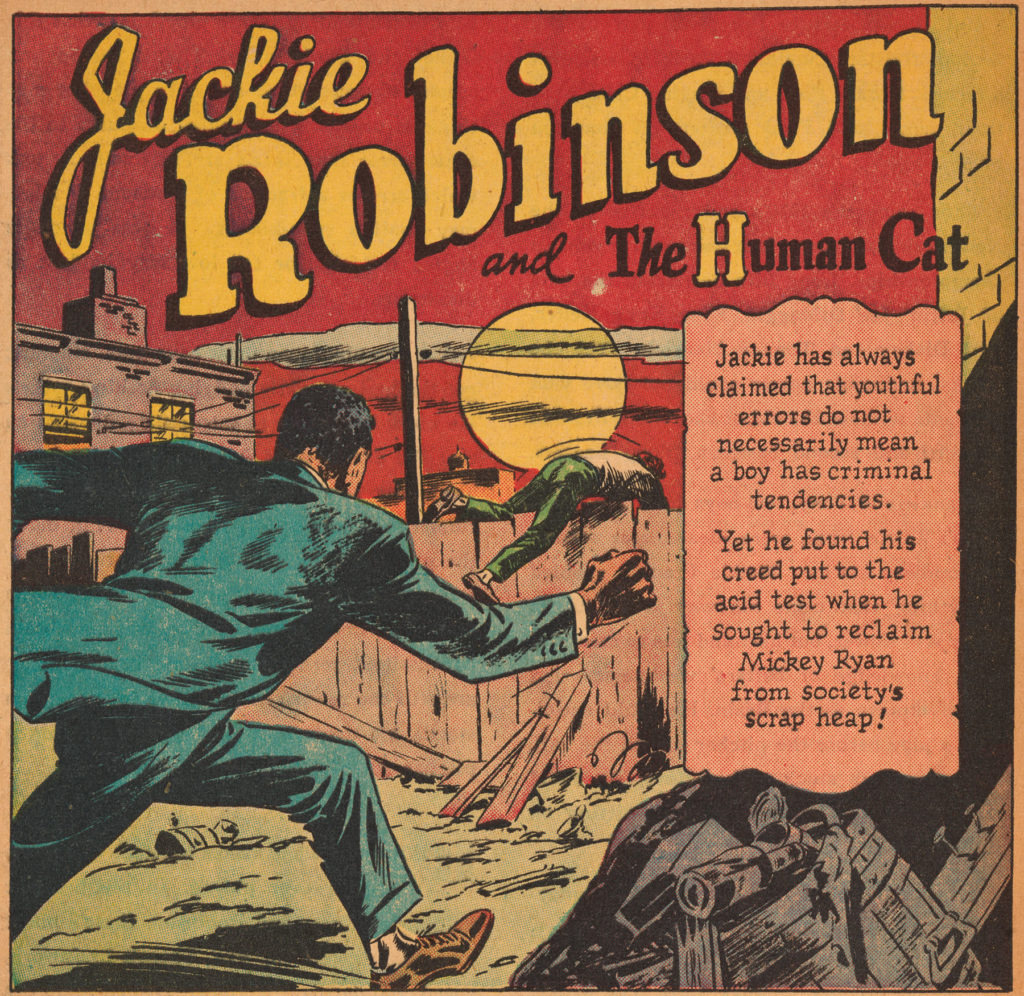

Jackie Robinson: Baseball Hero was such as success that Robinson—who was seeking ways to capitalize on his fame and to earn money outside of baseball—collaborated with Fawcett on a recurring series of five more editions through 1952. The subsequent issues continued to tell stories about Robinson’s baseball and athletic career and also featured fictional vignettes that showed Robinson mentoring children and rescuing them from a life of crime or disreputable behavior.

Jackie Robinson #4, for example, included a seven-page story titled, “Jackie Robinson and the Human Cat,” in which Robinson worked to redeem a star white teenage baseball player who had turned to criminal activities. The story’s tagline read, “Jackie has always claimed that youthful errors do not necessarily mean a boy has criminal tendencies. Yet he found his creed put to the acid test when he sought to reclaim Mickey Ryan from society’s scrap heap!”

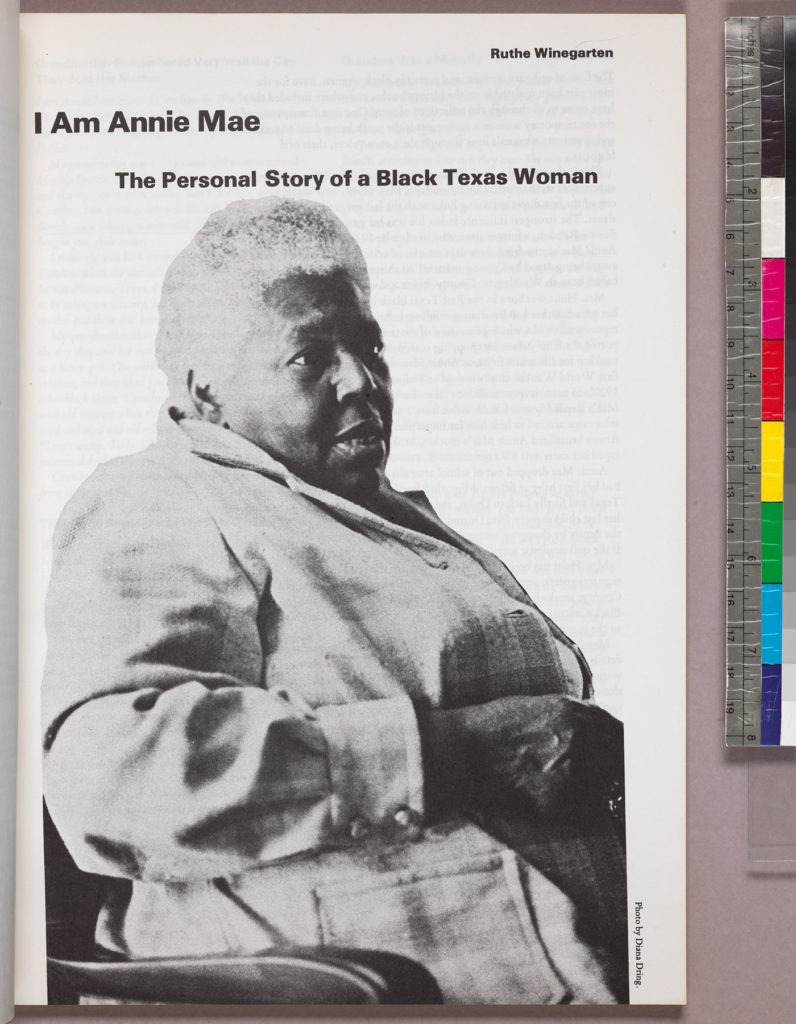

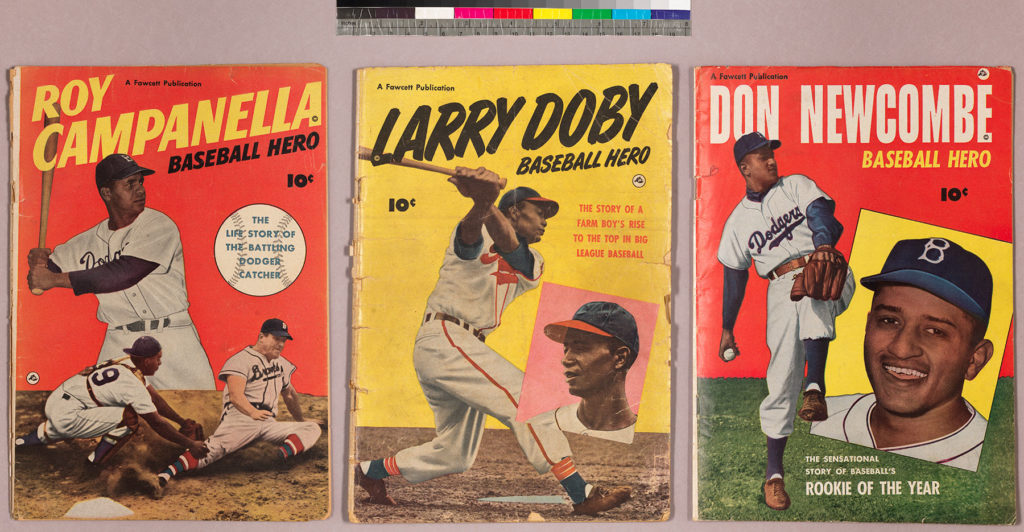

In addition to the Jackie Robinson series, Fawcett also took advantage of major league baseball’s fading color line by publishing similar single issue comic books in 1950 about other African American stars: Larry Doby: Baseball Hero (Cleveland Indians), Roy Campanella: Baseball Hero (Brooklyn Dodgers), and Don Newcombe: Baseball Hero (Brooklyn Dodgers).

The Lary Doby, Roy Campanella, and Don Newcombe comic books broadly followed the same model as the earlier Jackie Robinson: Baseball Hero issue, telling the inspirational stories of the players’ rise to the major league. The graphics illustrated their early years as athletes, the difficulties they faced due to their race, and their successful ascent to the big leagues.

The comics also tended to emphasize the good community work the players did, and the books continued to hold up these accomplished athletes as role models for children. The Fawcett “Baseball Hero” comic books provided all young readers—both Black and white—with otherwise hard to find positive and largely realistic portrayals of talented African American men.

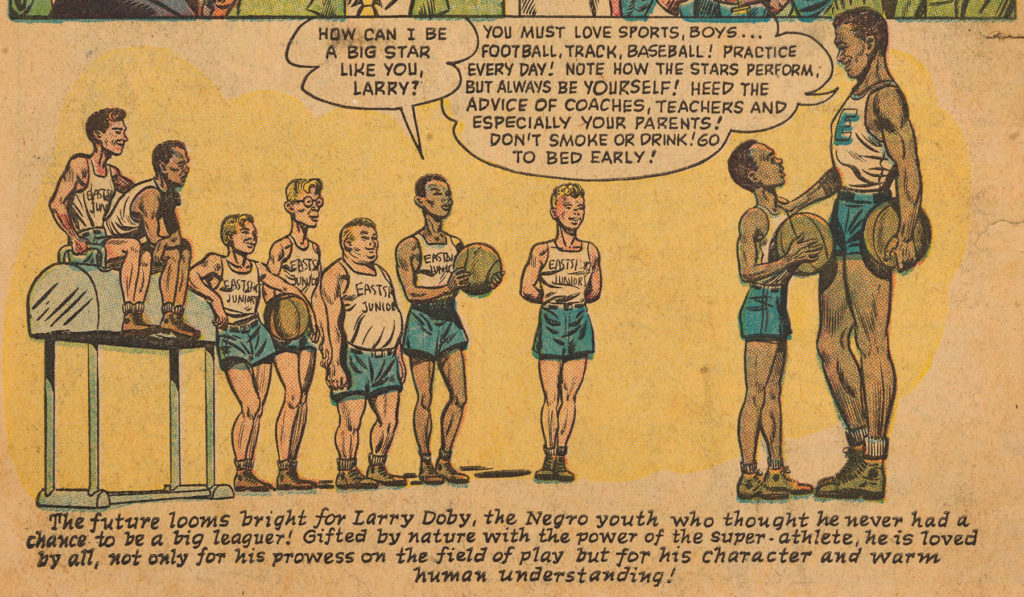

Larry Doby: Baseball Hero, for example ended with a scene highlighting this message. The final page of the comic recounted Doby’s triumphant return to his hometown of Paterson, New Jersey, after his first season in the major leagues. Although he was greeted by the Mayor, Doby was most excited to return to his alma mater of Eastside High School.

The comic’s final panel pictured Doby counseling and providing advice to the Black and white members of the Eastside High School basketball team. The eight players all listened intently to the major league star, and the final caption read: “Larry Doby… is loved by all, not only for his prowess on the field of play, but for his character and warm human understanding!”

For further reading:

“Jackie Robinson’s Life in Comics on Newstands Today [sic],” Atlanta Daily World 23 September 1949, p. 3.

Tom Hawthorn, “Jackie Robinson: Comic Book Superhero,” in Not An Easy Tale to Tell: Jackie Robinson on the Page, Stage, and Screen ed. Ralph Carhart (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 2022).

Brian Cremins, “‘This Business of White and Black’: Captain Marvel’s Steamboat, the Youthbuilders, and Fawcett’s Roy Campanella, Baseball Hero,” in Desegregating Comics: Debating Blackness in the Golden Age of American Comics ed. Qiana Whitted (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2023).