by Rachel Bohlmann, American History Librarian and Curator

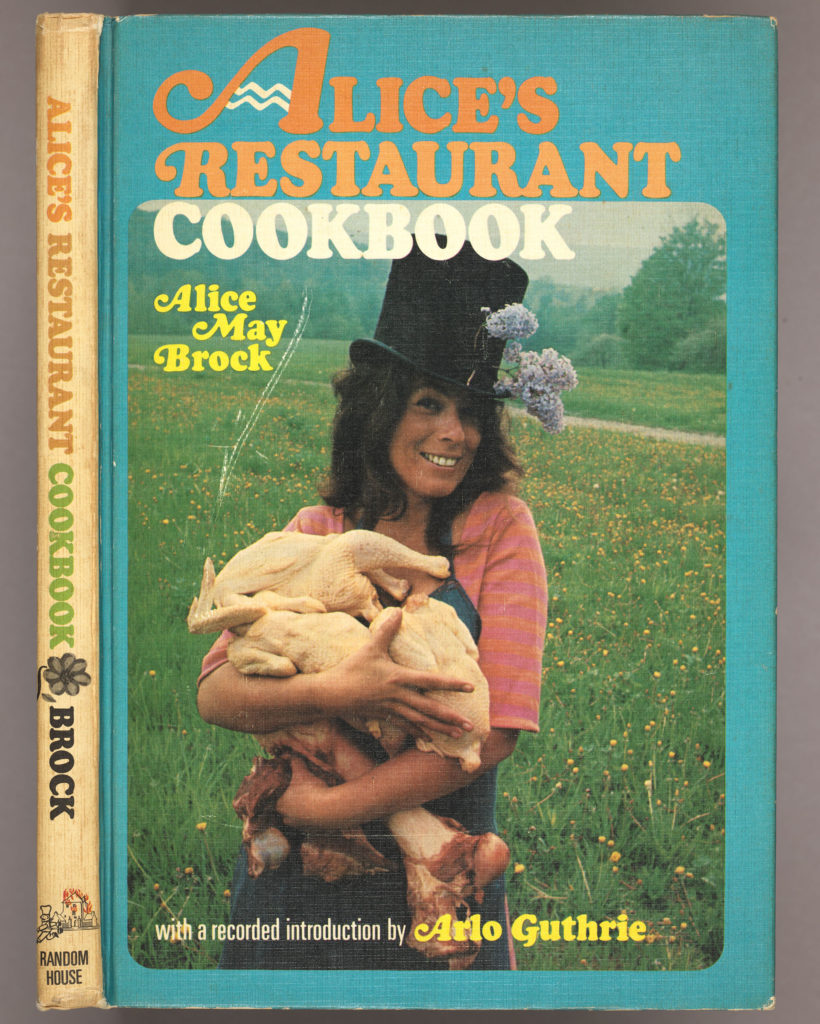

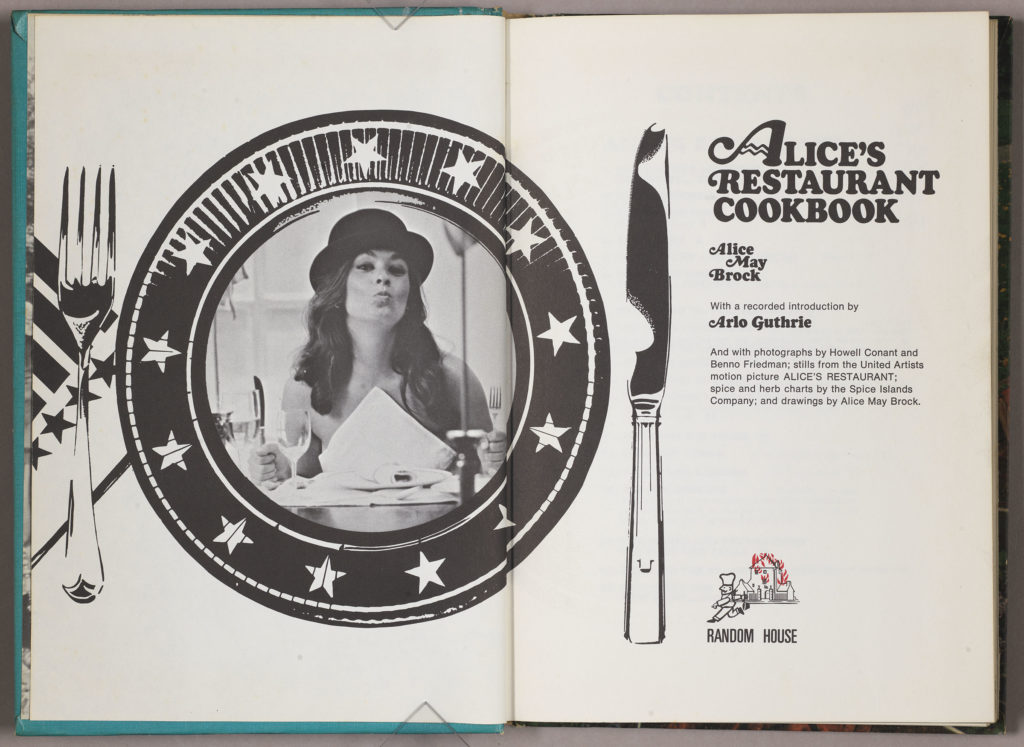

To celebrate Thanksgiving this year, Special Collections highlights Alice’s Restaurant Cookbook by Alice Brock (the Alice of Arlo Guthrie’s “Alice’s Restaurant” song) and the 1965 Thanksgiving that occasioned it. This is not a cookbook for Thanksgiving. It is a book that exists because of Thanksgiving. It is also a commercial, even nostalgic, artifact (produced by a mainstream publisher—Random House) about a countercultural moment already in the past when the book appeared in 1969.

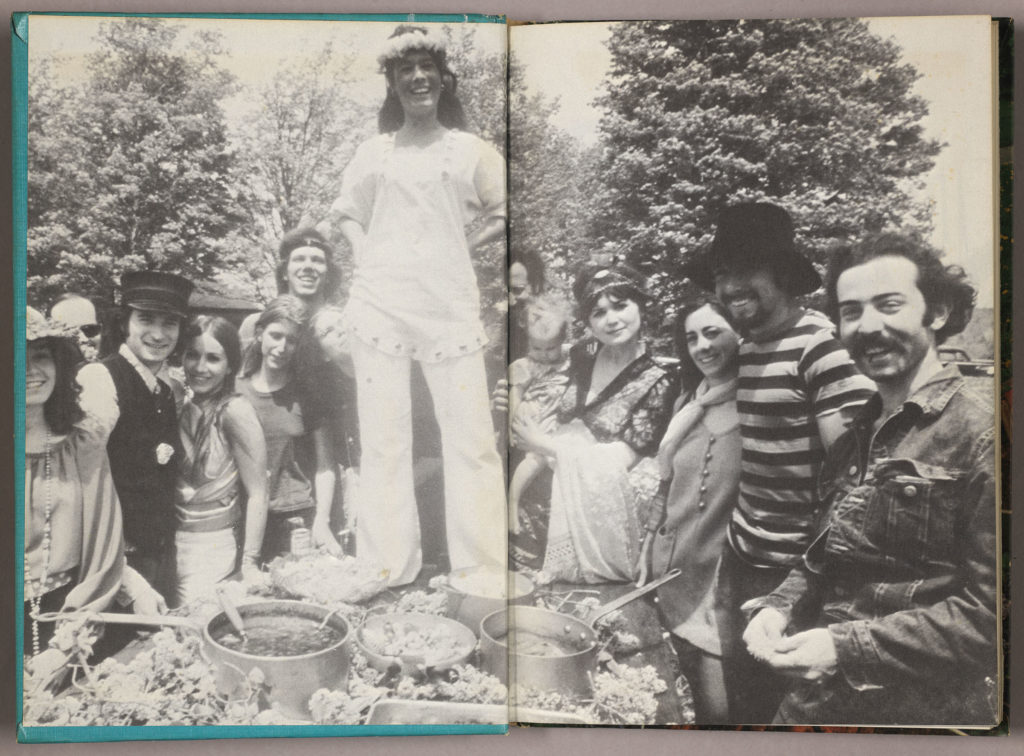

Alice Brock had opened a restaurant—The Back Room—in Stockbridge, Massachusetts in 1965. That Thanksgiving she hosted a gathering of friends that included Arlo Guthrie, the son of folk singer Woody Guthrie. The day after the festivities, Guthrie and a friend helpfully removed a large load of garbage from Brock’s house. The city dump was closed so the young men threw the trash down a nearby ravine. The owner of the property had the two arrested and criminally charged with littering. Brock bailed them out of jail and Guthrie was inspired to write a song, which became “Alice’s Restaurant Massacree,” released in 1967.

In the song, Guthrie relates his Stockbridge Thanksgiving, detention, and subsequent conviction. Then the song changes and Guthrie describes how he used his criminal record to secure a rejection from the New York City Draft Board and avoid military service during the Vietnam War. The song, which is 18 and a half minutes long, unexpectedly became an anthem of anti-Vietnam protests and an expression of countercultural rebellion. Since the 1970s it has also become a cultural icon around Thanksgiving. Today, many radio stations around the country play the song on this holiday.

Guthrie’s story/song also caught the attention of film director Arthur Penn, who adapted it into a film, Alice’s Restaurant. It was released in 1969 with leading roles by Guthrie and a small cameo by Brock (Patricia Quinn played Alice Brock in the film).

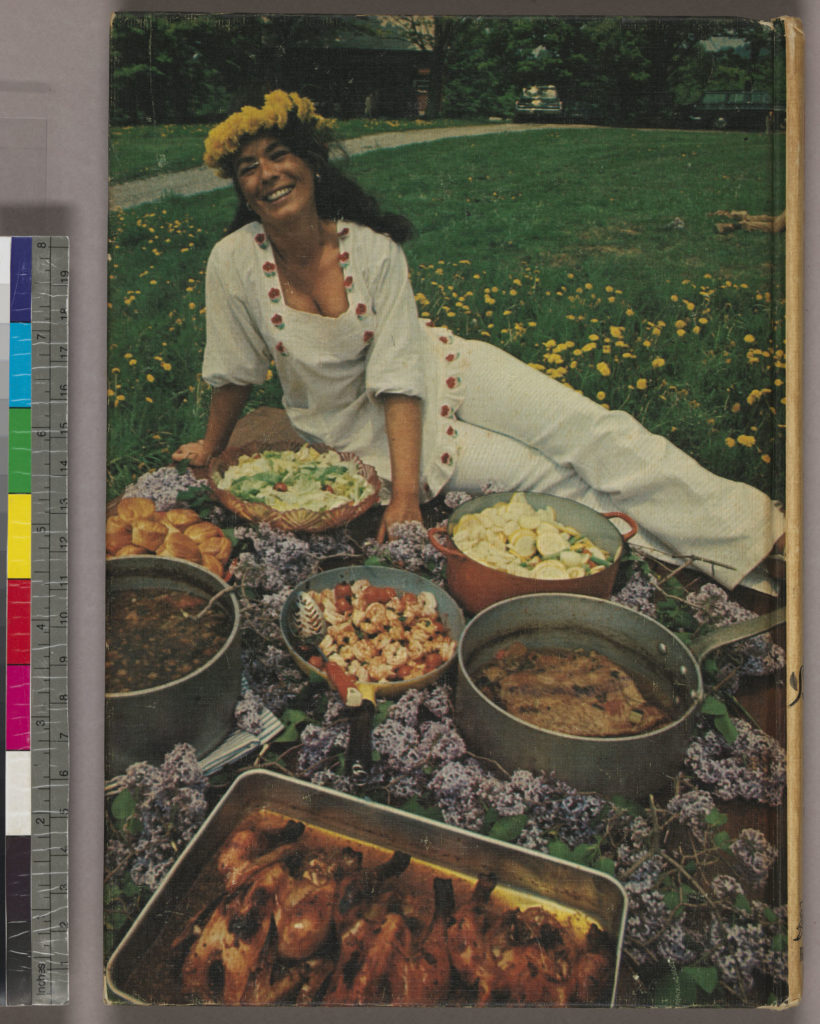

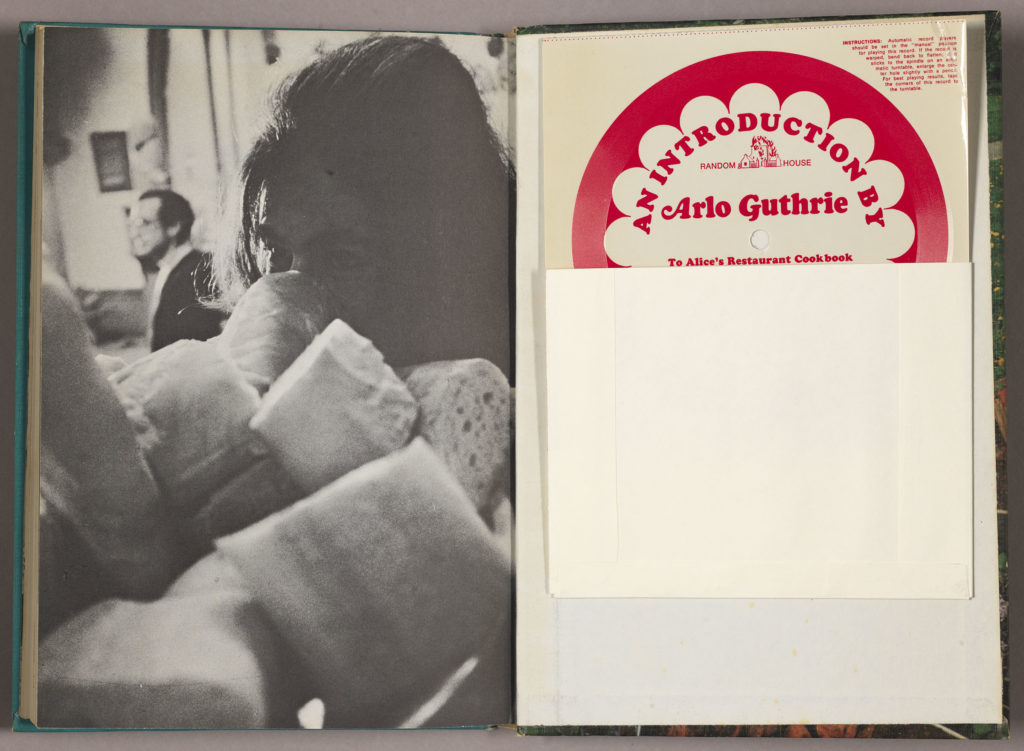

Brock published Alice’s Restaurant Cookbook on the song and the film’s commercial coattails. It contains image stills from the movie as well as a small, vinyl record tucked into a pouch attached to the back inside cover. The recording doesn’t include “Alice’s Restaurant Massacree,” but the disk underscores the book’s connection with Guthrie’s famous song with a short introduction by Guthrie and Brock followed by two songs by Guthrie. In “Italian-Type Meatballs” and “My Granma’s Beet Jam,” he puts the words of two of Brock’s recipes to music.

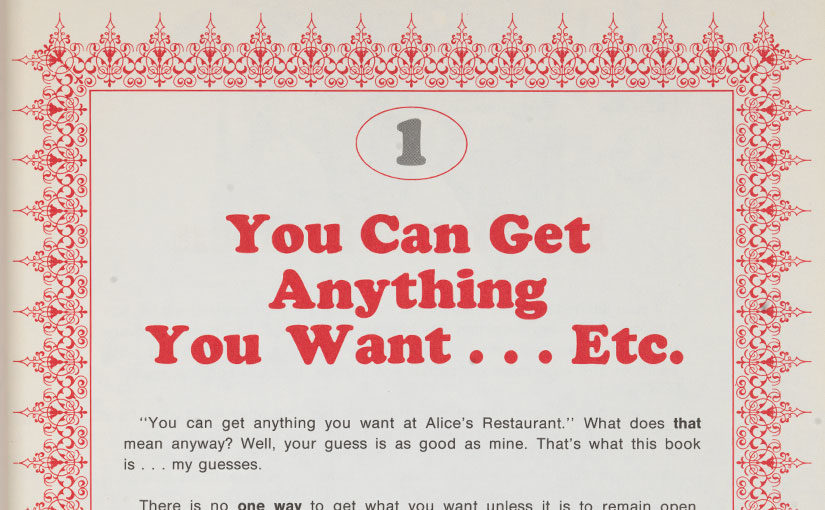

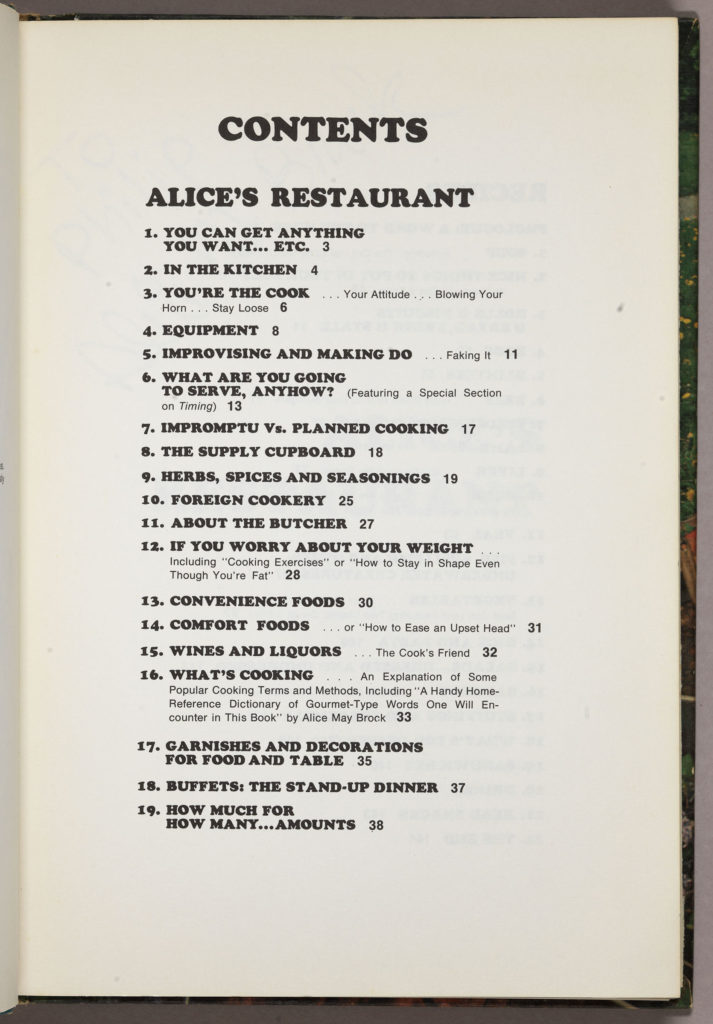

Brock’s cookbook captures her playfulness and openness along with the countercultural ethos of both her Thanksgiving gathering and her cooking. In her introduction, Brock riffs on the chorus of Guthrie’s song (“you can get anything you want at Alice’s restaurant”). “There is no one way to get what you want unless it is to remain open,” she writes. “Keep guessing. . . . No one has ever fried an egg without turning on the gas, but maybe this time if you look that egg straight in the eye and say ‘FRY,’ it will.” (p. 3). And no Betty Crocker cookbook had index entries for “Blowing Your Own Horn” and “Doctor, Get the” as well as “Used Chicken.

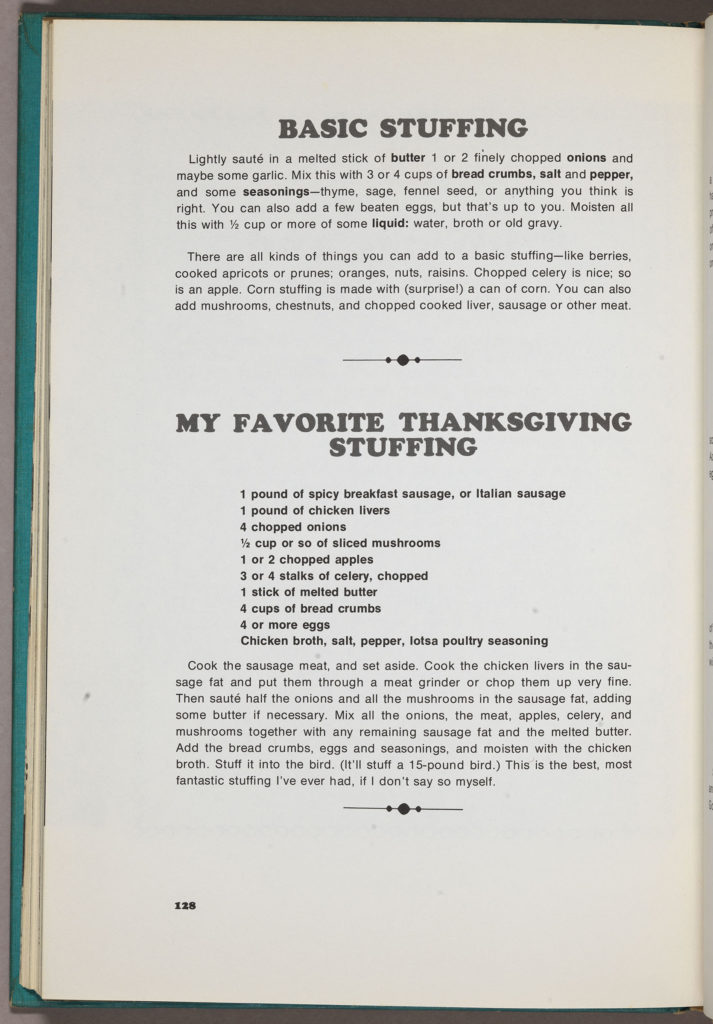

If you hope to find special recipes for cooking a Thanksgiving feast in Brock’s book, however, you’ll be disappointed. The section on “Turkey” takes up just a part of one page and the only reference to Thanksgiving appears in a chapter on “Stuffings And Forcemeat.” But as Alice Brock wrote in her author’s bio, she “[c]ooked good good food with a smile and other expressions . . . Bought a crummy diner . . . Turned it into a crazy-yummy-cozy restaurant . . . Thru it all Alice is a real live human bean—Still foolin’ around and still cookin’ . . .”

Happy Thanksgiving!

RBSC will be closed during Notre Dame’s Thanksgiving Break (November 25-26, 2021). We wish you and yours a Happy Thanksgiving!

Thanksgiving 2015 RBSC post: Thanksgiving and football

Thanksgiving 2016 RBSC post: Thanksgiving Humor by Mark Twain

Thanksgiving 2017 RBSC post: Playing Indian, Playing White

Thanksgiving 2018 RBSC post: Thanksgiving from the Margins

Thanksgiving 2019 RBSC post: “Thanksgiving Greetings” from the Strunsky-Walling Collection

Thanksgiving 2020 RBSC post: Happy Thanksgiving to All Our Readers