by Daniel Johnson, English; Digital Humanities; and Film, Television, and Theatre Librarian

James Gillray’s New Morality (1798) is a loaded work from one of England’s greatest caricaturists at the height of his powers. The eighteenth-century had witnessed a flowering of both English art generally (with, for example, the establishment of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1768), and caricature specifically, especially in the work of Gillray’s predecessor, William Hogarth (1697 – 1764; for an example in RBSC, see Hogarth’s illustrations for Hudibras, below), although some care should be taken with terminology. Hogarth was concerned enough by the slight implied by “caricature,” that he created a print in 1743, “Characters and Caricaturas,” to emphasis his separation from the latter style. As the editors of the Public Domain Review write, “for Hogarth the comic character face, with its subtle exploration of an individual’s human nature, was vastly superior to the gross formal exaggerations of the grotesque caricature.”

Comic grotesquery would remain controversial, but it provided a powerful vehicle for visual expression, and its exaggeration need not imply a lack of technical mastery. Gillray was an early member of the Royal Academy (admitted April, 1778), and during “a sabbatical” from satirical work in 1783-85, he produced capable, non-satiric prints ranging “from nostalgic pastoral illustrations to ‘eyewitness’ reconstructions of celebrated marine disasters” for Robert Wilkinson” (Hill xx). His failure to “secure commissions” from Benjamin West and John Boydell (an example of whose famous Shakespeare illustration commissions, featured in the RBSC’s “Constructing Shakespeare” Spotlight Exhibit in 2016, can be found in RBSC holdings Graphic Illustrations and A Collection of Prints), helped determine his future direction; by “the early nineties Gillray finally decided to devote himself fully to the profession of caricature” (Hill xxi). Although his earlier “commercial failure was absolute and ignominious, yet it is paradoxical that his laborious hours cutting and notching with his engraver’s burin and stippling tools should have immeasurably strengthened his hand as a caricaturist” (Godfrey 15). Nor was capturing the exaggerated likenesses a trivial exercise. Without the benefit of willing models, let alone photographs, artists had to hunt “on big game safaris in the wilds of Westminster” and memorize faces from afar – “Earl Spencer, when warned decades later that there was a caricaturist in the gallery of the House of Lords, shrank on the front bench and ‘sat huddled-up [with his] face and beard in his knees’” (Hill x).

By the time Gillray produced The New Morality, in 1798, he was making some of his “most artistically brilliant and inventive images” (Hallett 36). He had also settled down from the pose of “a detached, cynical ‘hired gun,’ concealing any actual political convictions beneath a veil of ambivalence and irony” to a closer apparent alignment with the Tory government, which some allege was stirred by “a secret annual pension of £200” from 1797-1801 (Hill xxii and Hallett 35). Indeed, The New Morality was commissioned for the Anti-Jacobin Magazine (though also issued on its own) to go along with the poetical “New Morality” of George Canning, politician and eventual prime minister in 1827. The imputation of bribery was a detractor and source of embarrassment for some critics, though Gillray’s sympathies had started to manifest some years before the pension.

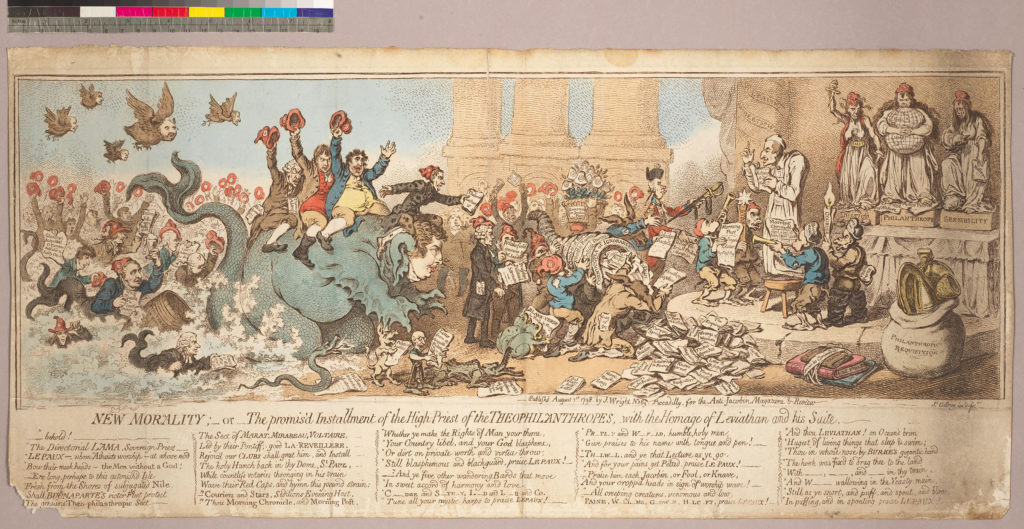

The allegorical density of The New Morality makes the image ripe for close and detailed analysis – an intense engagement supported by the magnifying glass of high resolution scanning at RBSC. The bookseller, Bernard Quaritch Ltd, describes the tableau thus:

On the right of the print is Lépaux, a member of the French Directory who had given prominence to Paine’s Theophilanthropic sect, preaching from a stool and attended on his dais by grotesque Jacobin creatures, while behind him are the monstrous embodiments of Justice, Philanthropy (devouring the globe) and Rousseauian Sensibility. Prostrated immediately before Lépaux are the two ass-headed figures of Coleridge and Southey, clutching their works, behind whom is seen the ‘Cornucopia of Ignorance’ and a flowerpot of plants resembling Jacobin hats with cockades. Out of the water rolls the monstrous Leviathan, resembling the misled Duke of Bedford (he has a fishhook through his nose), on whose neck rides the filthy Thelwall; on his back are Fox, Tierney and Nichols, waving their red bonnets[.] Emerging from the waves behind the Duke are diminutive sea-monsters and horned creatures clutching their works, while in the sky fly five grotesque birds, all representing various political radicals. In the foreground is a train of monsters: Paine as a crocodile (crying proverbial tears); Holcroft as a dwarfish figure in spectacles and leg-braces (Southey thought the likeness to be accurate); Godwin as an ass reading his Political Justice; and a snake representing David Williams, founder of the Royal Literary Fund.

(N.B. The acquisition of Gillray’s New Morality at RBSC coincides with the acquisition of a number of books written by “the filthy Thelwall”; RBSC’s holdings of Thelwall can be found here). The image’s breathless and baroque movement across a vast cultural landscape of major and minor political, philosophical, and poetical figures is a visceral reminder that a highly charged, partisan news media is hardly a twenty-first century invention. Graphical satires “functioned as powerful supplements to, and interventions in, the predominantly textual sphere of political journalism and printed social commentary [… in which newspapers and journals] were frequently subsidised [sic] by either the government or the opposition, and consequently functioned as propagandist mouthpieces for their policies” (Hallett 35).

The physical qualities of the print are noteworthy in their own right. While the plate was designed for mass printing, the print itself bears witness to bespoke treatment in its coloration. According to Draper Hill, “individual copperplate etchings, available plain or exquisitely colored by hand, were collector’s items from the moment of issue,” and perhaps most interesting, we “know nothing” of Gillray’s “colorists; presumably they were teams of extremely accomplished ladies working in relays” for the female printseller Hannah Humphrey, at whose residence Gillray lodged (ix, xi). Ironically, Gillray’s “technical wizardry” with his engraving tools “would be concealed by the bright hand colouring which became the norm for a published print” (Godfrey 15). Nevertheless, the colorized prints bear witness to a partnership with artisan labor, rendering each one a unique production.

Works Cited

Godfrey, Richard T. “Introduction.” James Gillray: The Art of Caricature, Tate Gallery Publishing, 2001, pp. 11–21, 38.

Hallett, Mark. “James Gillray and the Language of Graphic Satire.” James Gillray: The Art of Caricature, Tate Gallery Publishing, 2001, pp. 23–37, 39.

Hill, Draper, editor. The Satirical Etchings of James Gillray. Dover Publications, 1976.