We join the Library of Congress, National Archives and Records Administration, National Endowment for the Humanities, National Gallery of Art, National Park Service, Smithsonian Institution and United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in commemorating and encouraging the study, observance and celebration of the vital role of women in American history by celebrating Women’s History Month.

Second-Wave Feminist Articles from an Underground Newspaper

by Rachel Bohlmann, American History Librarian and Curator

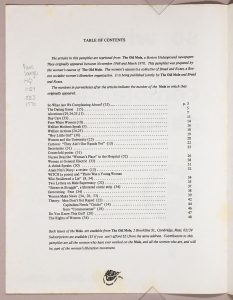

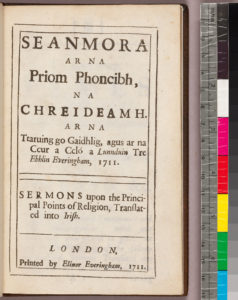

So What Are We Complaining About? is a 48-page booklet of feminist articles collected and reprinted from the pages of an underground newspaper, the Old Mole, published in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The booklet’s publication was a joint venture of the Old Mole and Bread and Roses, a socialist women’s liberation collective, in 1970. The booklet was created by the women’s caucus, a group within Bread and Roses. The Old Mole, which appeared bi-weekly from 1968 to 1970, was the publication of the Harvard chapter of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS).

It’s not surprising that Bread and Roses women wished to collect and recirculate this content. Among the collective’s founders were activists and a historians Meredith Tax and Linda Gordon. Both women contributed significantly to the feminist movement in the United States from the 1970s and wrote much of its history. Reprinting was one of the best and only ways to publicize content that had already appeared in print, often in small, locally-circulated and ephemeral papers like the Old Mole.

Tax and Gordon founded Bread and Roses in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1969 as a women’s liberation organization. They chose “Bread and Roses” because it both references an historic labor strike by women (Lawrence, Massachusetts in 1912) and it captures what the collective wanted to attain for women—economic opportunity (“bread”) and quality of life (“roses”). Over the nearly two years the collective was active, it attracted hundreds of members, many of whom were clerical workers who faced poor wages and working conditions. A number of reprinted articles address these problems. The collective took action by forming a union, 9to5, for local clerical workers. Another legacy project became the women’s health resource, Our Bodies, Ourselves, which developed out of the collective’s 1970 initiative, “Women and Their Bodies: A Course.”

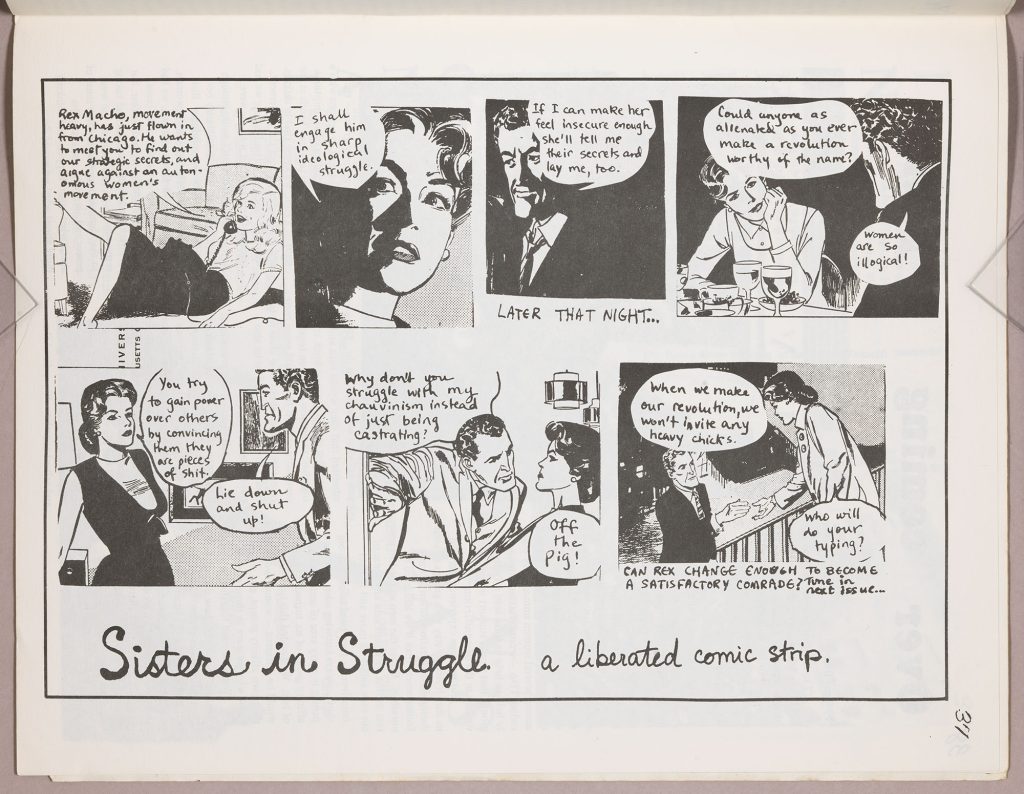

Other features included in this short volume are Bread and Roses’ declaration of women’s rights (March 1970); a satirical, “liberated,” comic strip; and a short history about the establishment of International Women’s Day.

So What Are We Complaining About? is a new acquisition in Rare Books and Special Collections and is part of a growing collection of second-wave, feminist periodicals and newspapers.