by Greg Bond, Sports Archivist and Curator, Joyce Sports Research Collection

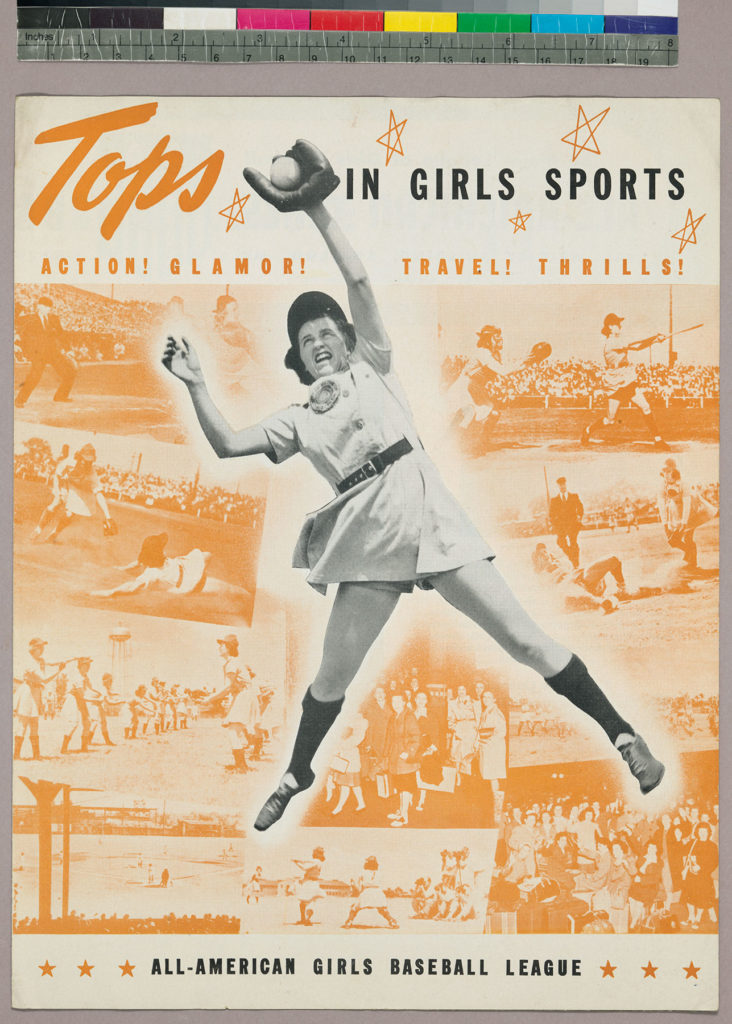

“Action! Glamor! Travel! Thrills!”

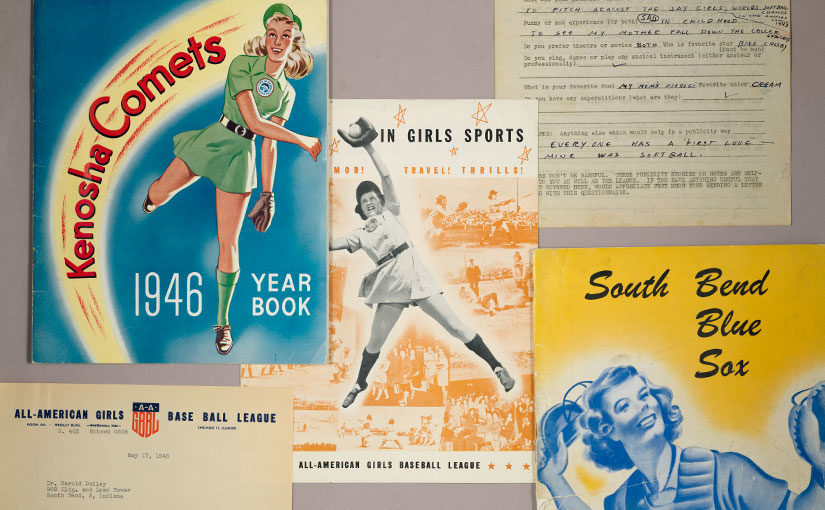

A 1948 promotional flier for the All American Girls Baseball League (AAGBL)—which billed itself as “the tops in girls sports”—used these enticements to encourage women to try out for the league. Inside, the pamphlet further described “action-packed… All-American Girls baseball” as a “game of sensational growth and popularity with an equally brilliant future” and promised “a sport unlike any other in existence and one which offers real opportunities to the young girls of every city, village, and hamlet of America.”

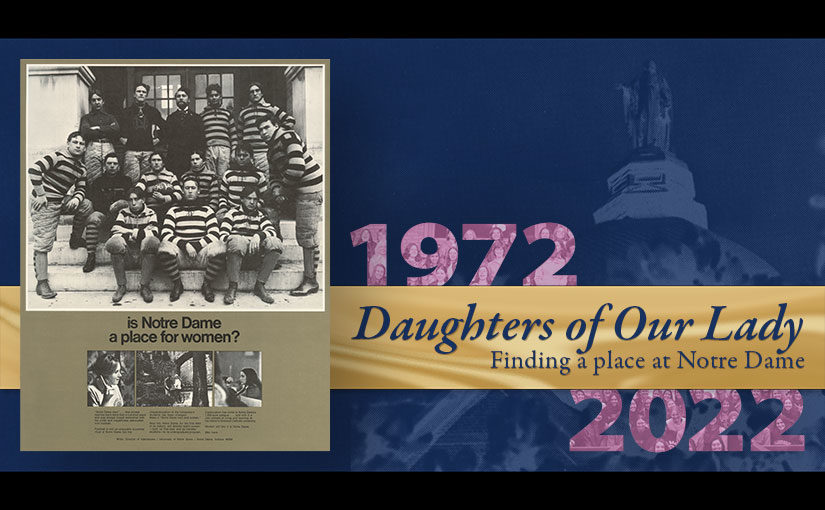

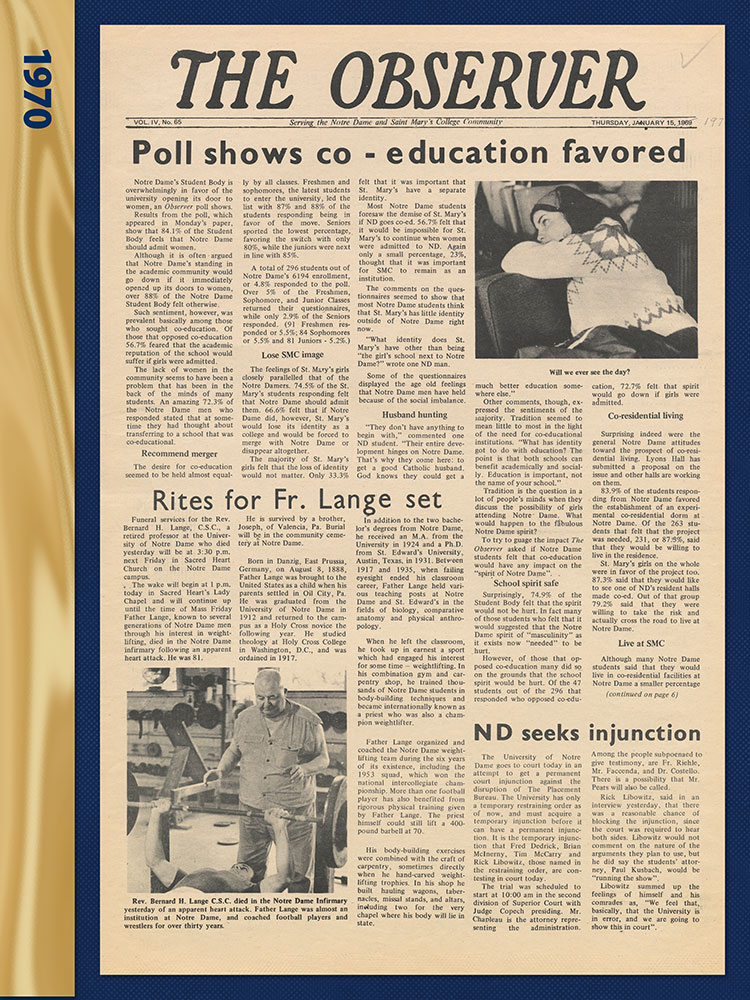

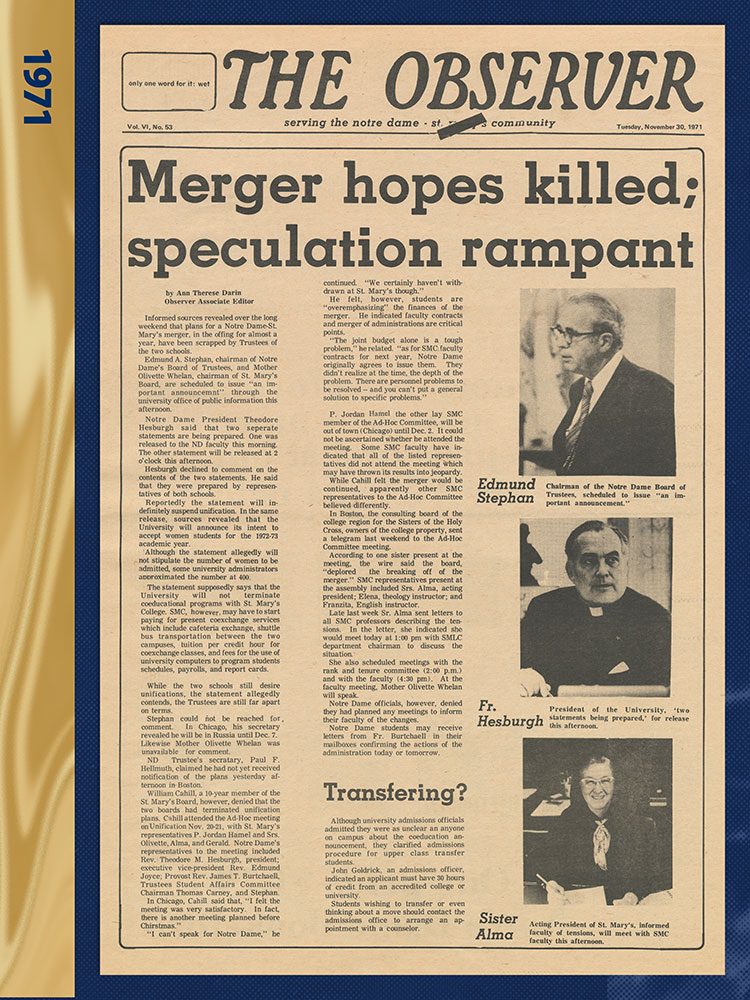

This flier comes from a remarkable All American Girls Baseball League manuscript collection housed in the Joyce Sports Research Collection in Hesburgh Libraries that documents the history of this important pioneering women’s sports league. A League of Their Own, a new Amazon streaming show about the league (that shares a name with the popular 1992 Geena Davis and Tom Hanks movie on the same topic) has re-focused attention on the actual history of the AAGBL and has also brought renewed interest in the unique AAGBL materials in the Joyce Sports Research Collection. Recent visitors and researchers to consult the AAGBL collection include Notre Dame undergraduate students from Professor Annie Coleman’s Sports and American Culture class and attendees at an AAGBL convention and reunion hosted in South Bend this past August.

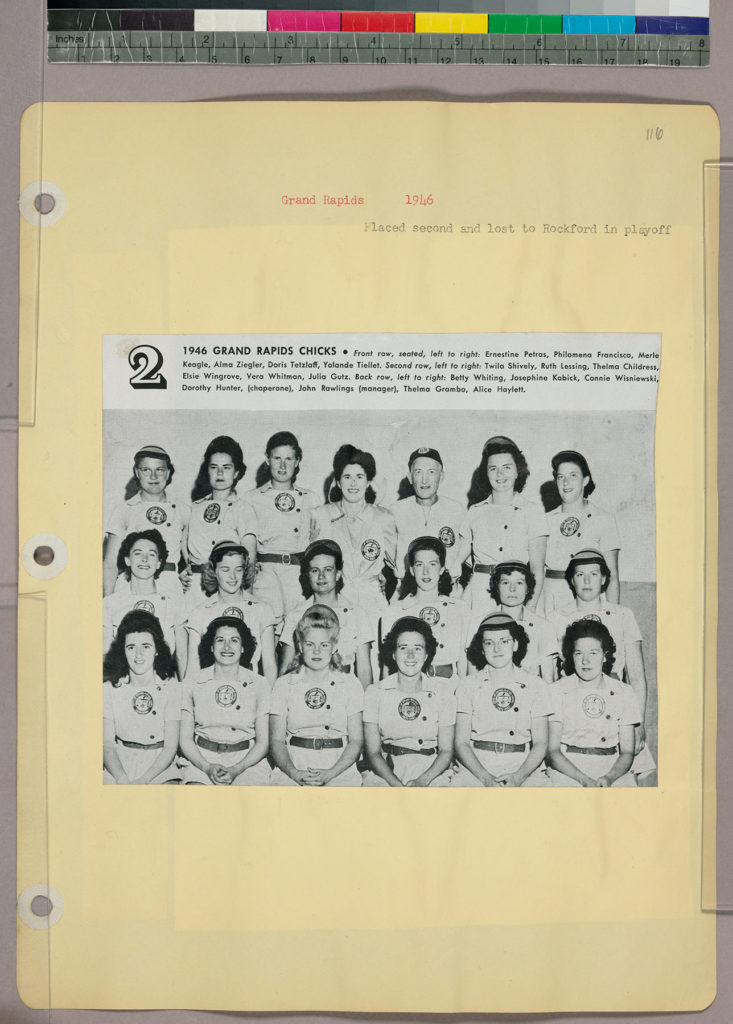

Founded in 1943 by Chicago Cubs owner Philip K. Wrigley and other baseball and civic leaders who worried that World War Two labor demands could threaten the viability of professional men’s baseball, the All American Girls Baseball League provided high-quality women’s sports in (mostly) mid-sized Midwestern cities like South Bend, Indiana; Rockford, Illinois; Racine, Wisconsin; Grand Rapids, Michigan; and others.

Although Wrigley quickly sold his stake in the league when it became apparent that major league baseball would survive during the war, the AAGBL continued for 12 seasons until 1954. In the league’s first seasons, the game was akin to fast-pitch softball, but, in ensuing years, the rules evolved—including overhand pitching and a smaller ball—to more closely resemble men’s baseball.

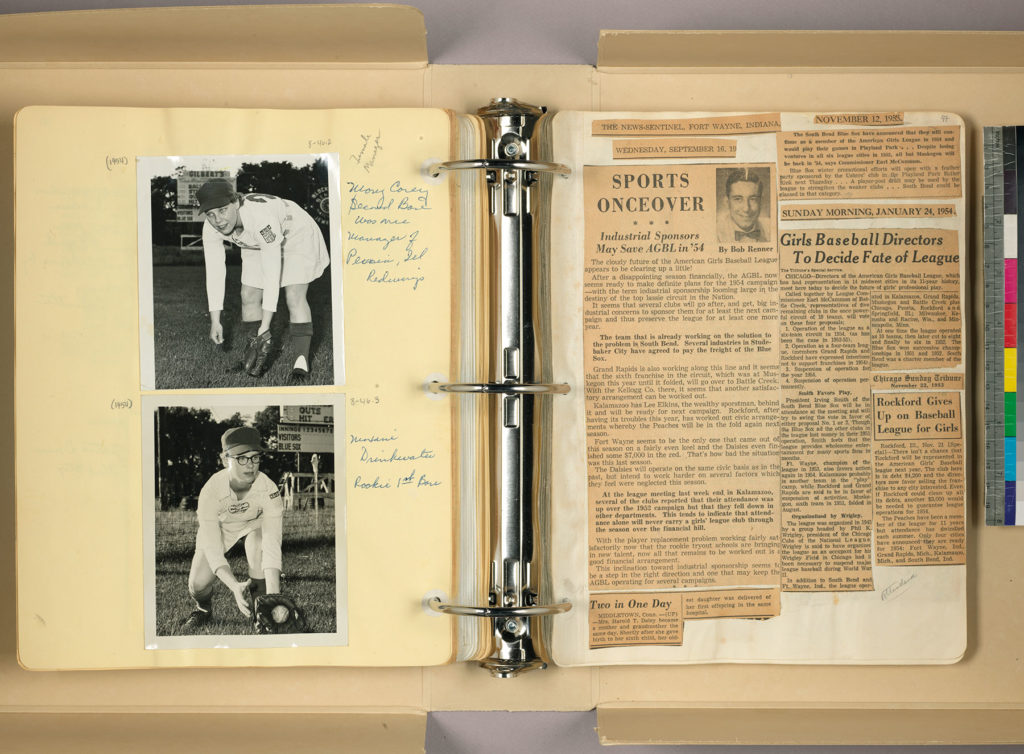

The AAGBL manuscript collection consists chiefly of the personal and collected papers of two men involved with the South Bend Blue Sox—one of two franchises (along with the Rockford Peaches) to compete in all 12 league seasons from 1943 to 1954. Harold T. Dailey, a South Bend oral surgeon, was a team administrator for most of the Blue Sox’s existence and served on the team Board of Directors from 1945–1952. Chet Grant managed the Blue Sox in 1946 and 1947.

Years later in the 1970s, Grant helped oversee the Joyce Sports Research Collection, and he facilitated the donation of these one-of-a-kind materials. The AAGBL collection includes a variety of formats, including correspondence, programs, yearbooks, photographs, financial records, scrapbooks, player questionnaires, clippings and more, all of which help to document the full history of the league.

“A High Standard of Conduct”

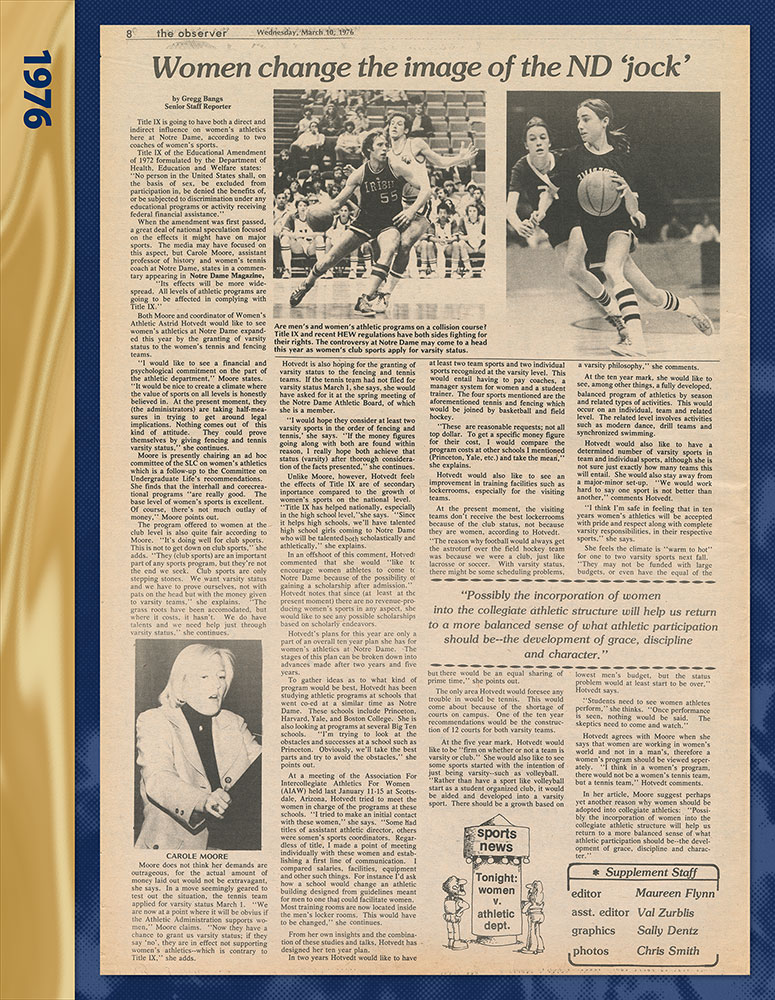

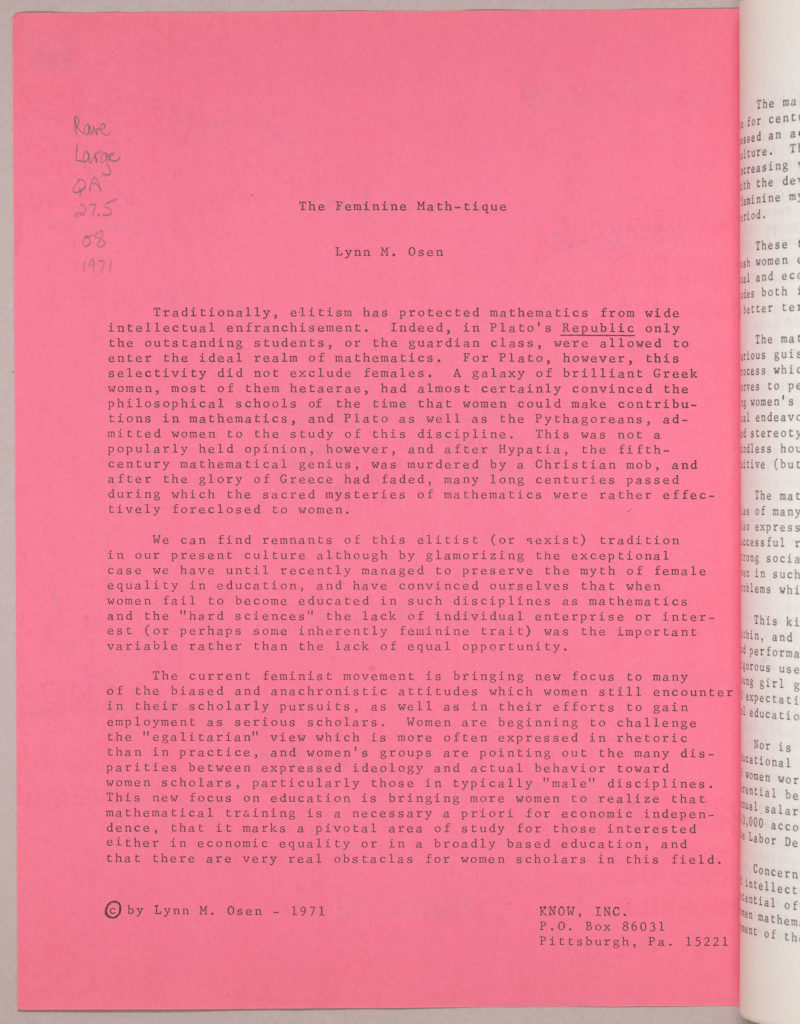

One important theme of the new Amazon League of Their Own series—and one that is well reflected in the manuscript collection—is the League’s emphasis on conventional ideas of femininity. Perhaps because the players were exceptional athletes, the male owners and administrators always insisted on promoting images of traditional feminine appearance and behavior—from the required uniform skirts to elaborate rules and regulations that (hoped to) govern player conduct. The 1948 promotional flier, for instance, assured fans and prospective players that “All-American girls… are selected for their athletic ability and baseball ability as well as femininity, character, and deportment. A high standard of conduct and behavior is maintained at all times.”

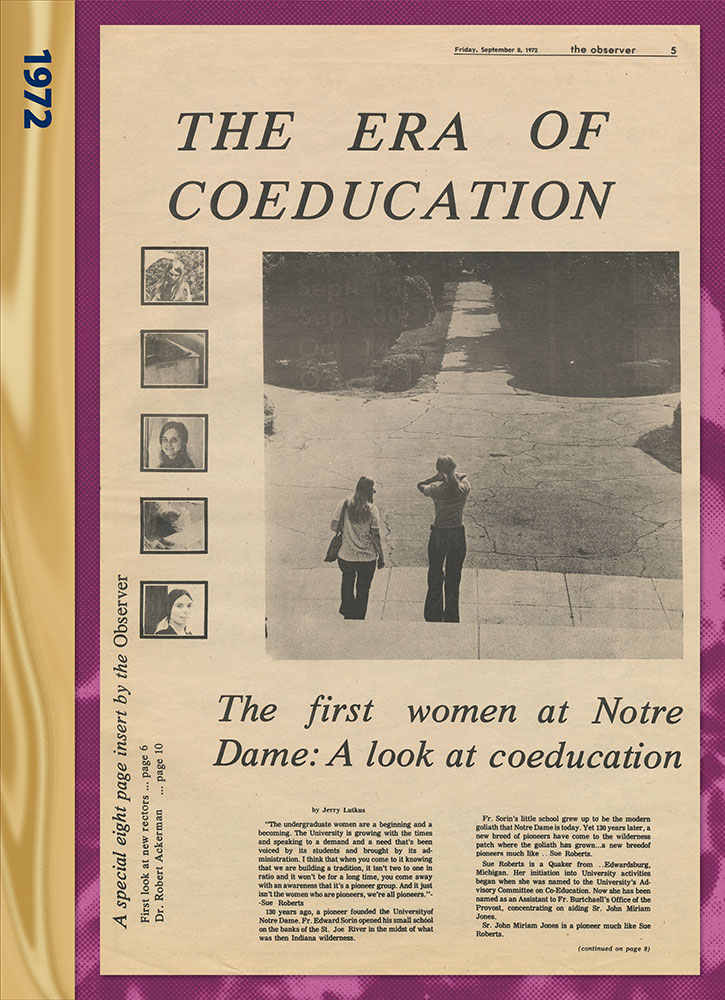

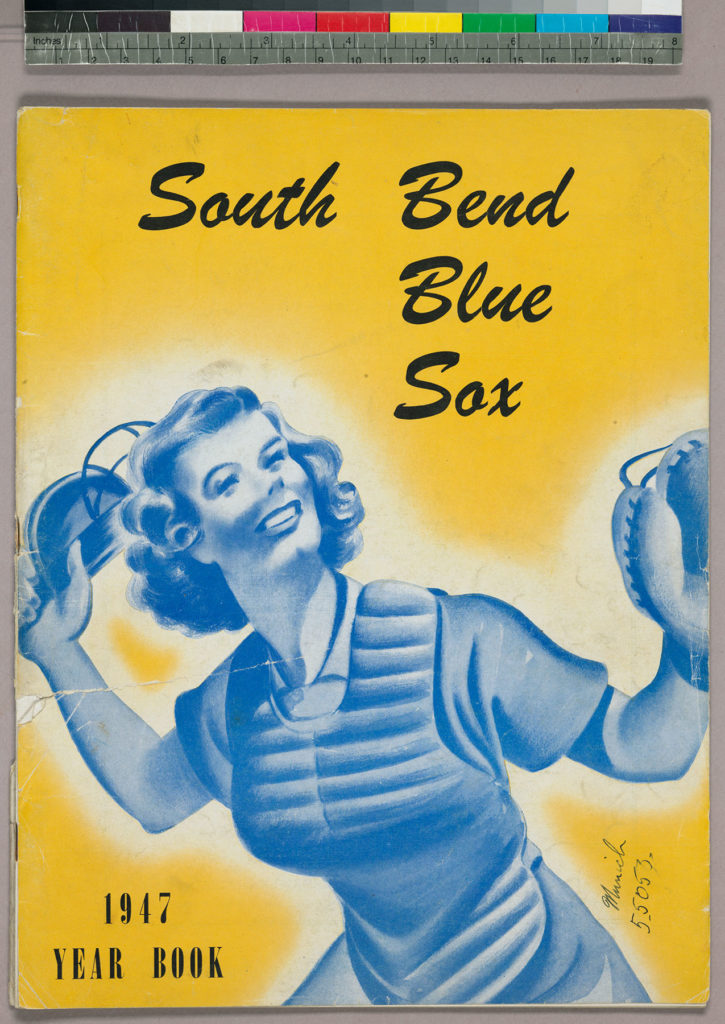

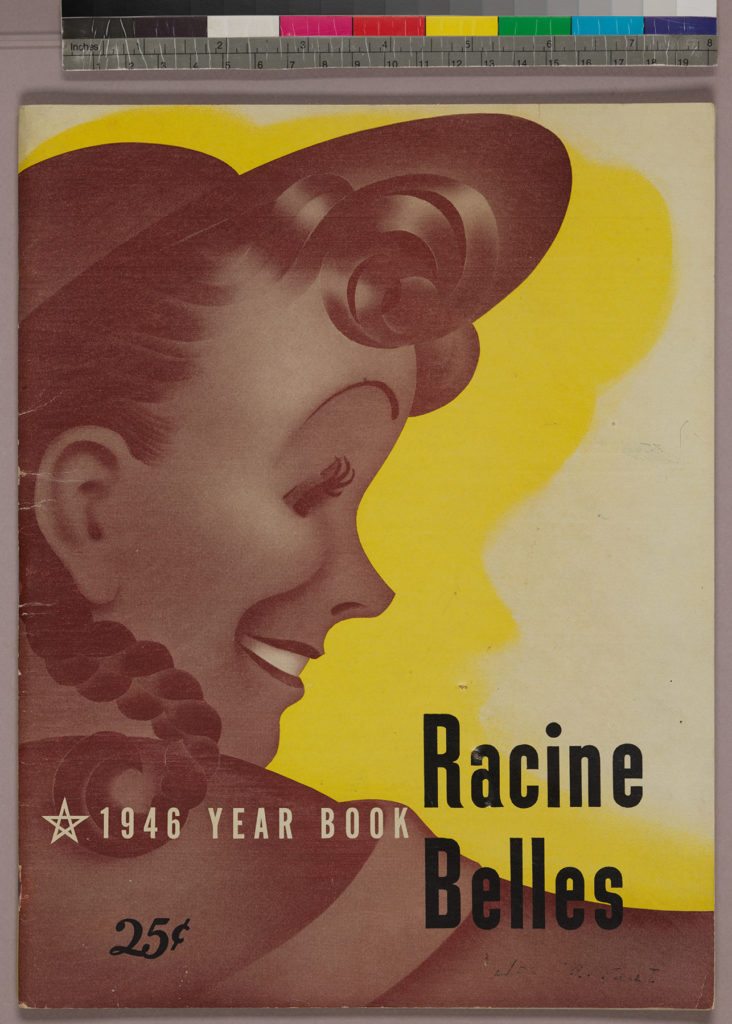

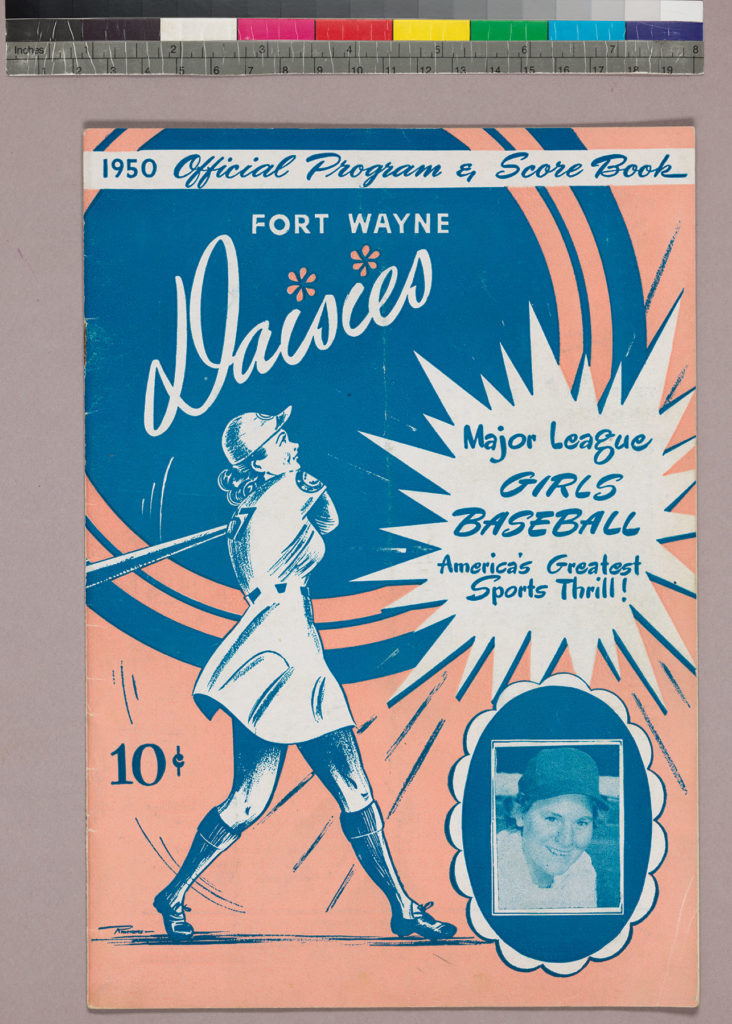

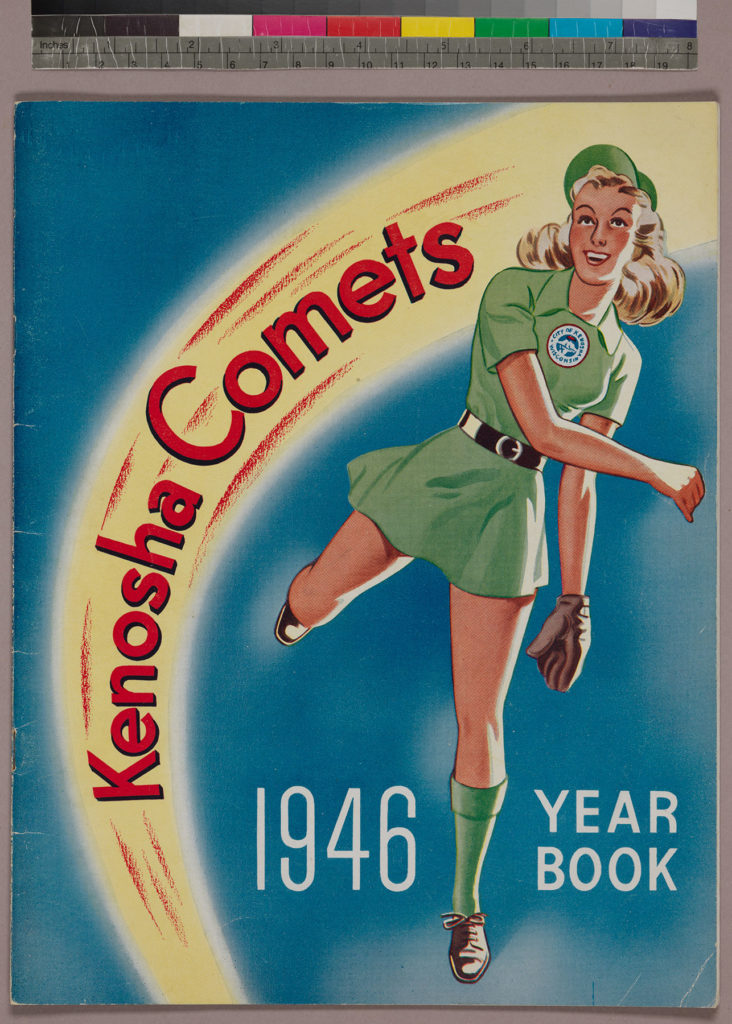

Printed material from the league, too, consistently featured stylized images that emphasized conventional ideals of feminine appearance. A few examples from the AAGBL collection include the 1948 South Bend Blue Sox Yearbook, the 1946 Kenosha Comets Yearbook, and the 1950 Ft. Wayne Daisies Official Program.

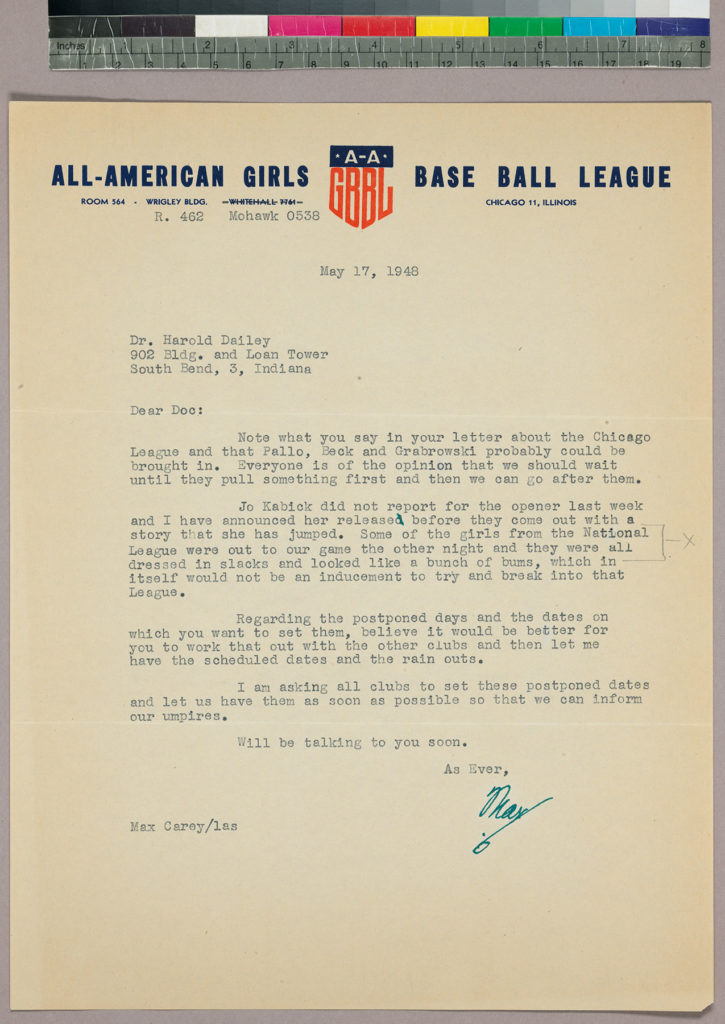

Internal correspondence, also, addressed this issue. In a May 17, 1948, letter, for instance, League President Max Carey, a former major league baseball player, wrote Harold Dailey that “some of the girls from the National League [National Women’s Softball League] were out to our game the other night, and they were all dressed in slacks and looked like a bunch of bums, which in itself would not be an inducement to try and break into that league.”

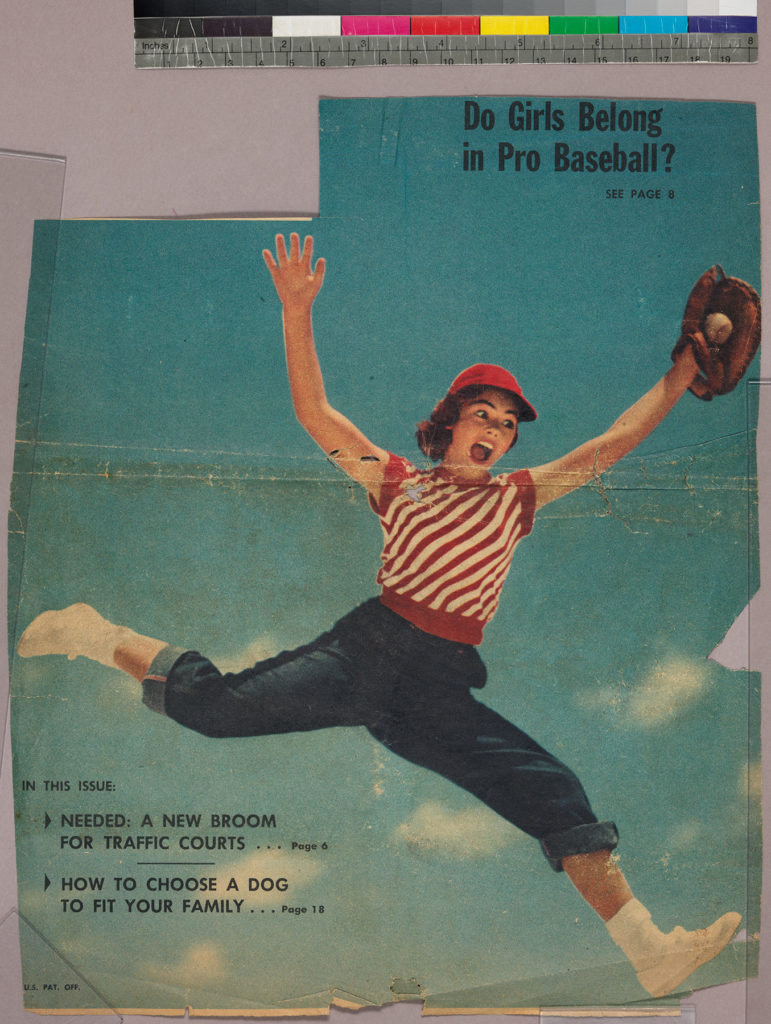

Despite such precautions by the League and despite the AAGBL’s high-level of play and popularity in league cities, some in the public remained skeptical about the propriety of women participating in a traditionally male pastime. This undated clipping from the AAGBL collection, for example, asked “Do Girls Belong in Pro Baseball”?

The Amazon League of Their Own series also explores its characters’ sexuality and LGBTQ issues. League administrators in the 1940s and 1950s encouraged conventional heterosexual relationships for the players and promoted traditional heterosexual norms in their publicity material. Concerns about player sexuality do not seem to be often overtly mentioned in the surviving league records, but there are still some tantalizing glimpses of the issue.

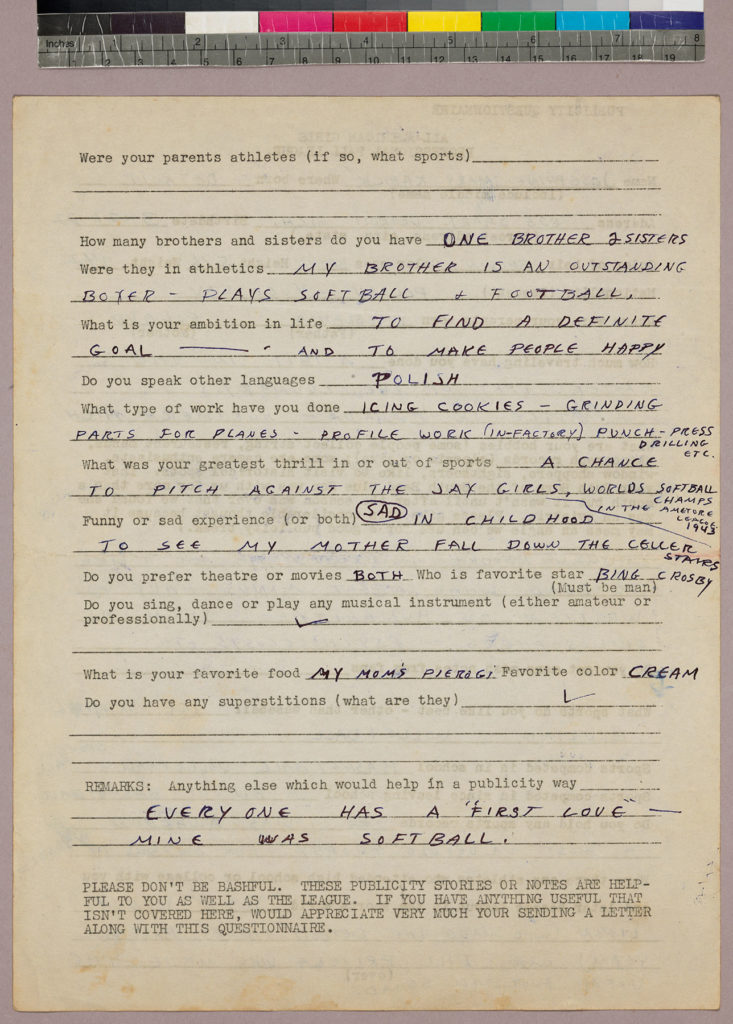

The AAGBL manuscript collection, for example, includes a fascinating set of 76 promotional questionnaires completed by league athletes in about 1944. The forms solicited information about the players’ backgrounds, experiences, and interests, and instructed the women: “please don’t be bashful” with your answers. One question, though, did require more discretion. In a section about entertainment, the questionnaire invited players to name their “favorite star”—but then quickly stipulated that the answer “must be a man.” League administrators evidently wanted to avoid any suggestion that players might be interested in other women.

Despite such contemporary gender and sexual politics that constrained the behavior and self-expression of players, more than 600 athletes appeared in the AAGBL during its 12 years of competition. These women excelled on the field, unabashedly exhibited their athletic prowess, demonstrated that there was an audience for high-caliber women’s sports, and, in their own way, helped to challenge and re-shape the very same strict societal gender norms the league sought to enforce.

The athletes were doubtless aware of the league’s cultural significance. But many players were also simply thrilled to be playing ball and relished the opportunity to test their mettle against some of the best women athletes in the country. Pitcher Jo Kabick probably spoke for many of her league-mates when she wrote enthusiastically on her 1944 publicity questionnaire: “Everyone has a ‘first love’—mine was softball.”

The All American Girls Baseball League Collection is open to the public and available to researchers. Please email rarebook@nd.edu to make an appointment to consult the collection.