My 7-8 weeks spent in Radolfzell, Germany can be described as a great triumph. Speaking German, in almost any situation, became easier and easier. Several times people asked me where in Germany I grew up, only to reveal for me to reveal that I am not originally from Germany at all. One time an acquaintance even commented that she could tell I spent time in Stuttgart by the way I spoke or some dialect phrases I occasionally used. The ability to assimilate both linguistically and culturally—the ability to blend in like an ordinary person—is ironically a grand accomplishment in the process and years-long commitment of learning a language and a culture. I have been learning German for more than half of my life: a delightful adventure that will only continue.

During my time in Radolfzell, however, a great reward for my efforts became apparent—in the most simple, everyday ways. With each day in Radolfzell, I felt more “at home.” This revelation was deeply personal, as growing up both in Germany and the United States permanently changed my identity, future plans, language, and habits. However, besides my language studies, I remain in the United States somewhat disconnected from Germany, a place I would consider my second home. But being in Germany and partaking in everyday “normal” life felt not only familiar but right for me. I felt more and more comfortable and felt that I was supposed to be there—no longer did I have to “earn” my way, but rather I was able to be there and participate in the community just normally and comfortably. No longer did I feel like an obvious outsider, but rather just normal in the surrounding society.

A significant advantage of studying and staying in Radolfzell was the constant immersion. Even when revealing that I came from the United States or having unexpected difficulty with conversation, my colleagues and counterparts would always speak German to me. No one switched to English for the sake of ease, but rather, many locals were adamant to speak with me and other language learners in German, which allowed us the opportunity to struggle a little and consequently learn. Those hard-won new phrases and words imprint themselves better in our memory.

For instance, during my second week in Radolfzell, I ventured into a local clothes shop and eventually asked one of the owners for a changing room. However, right when I asked that, I simultaneously realized I had no idea what the word “changing room” was in German. I could use medical- or literature-specific words in German, but I found several ordinary words, imperative to daily situations, missing in my vocabulary. I stumbled over my sentence, ultimately asking in German: “Do you have….anywhere where I can try on this dress?” She laughed, gauging that I was a foreigner, and before pointing me in the right direction, kindly told me the word for dressing room: “Die Kabine.” Over the next few weeks, I visited various stores, often shopping with friends, and each time, I re-used this word so often that it became effortless to retrieve from my vocabulary.

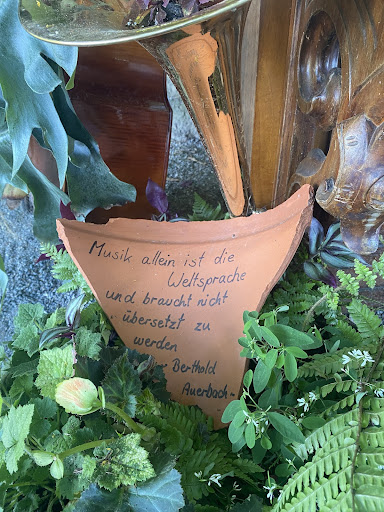

Each word learned in a foreign language has a story or a memory, especially when learned in an immersion setting. And the associated experiences allow these words to be more accessible when speaking, writing, and understanding—to the point of being effortless. When reading, writing, speaking, and hearing German, I no longer have to translate anything into English, for I automatically process it in German, even if I don’t completely understand it. It is almost ironic how one meticulously studies grammar and dissects sentences to then understand the inner workings of a language and then often “feel” how it should sound or read. Right now, my brain feels like an absolute mishmash of German and English, which is delightful. Even as I write this entry, I think of German words that would fit sometimes before coming to the corresponding English word. But that is with such a triumphant feeling because the language contains its own expression and feeling that one somehow, after much hard work and exposure, understands and can use comfortably.

Now I will do my best to recount my adventures, describe Radolfzell, and summarize my time there.

My host family was a lovely older couple, and I lived on the top floor of their four-story house, with my own little one-room apartment. Although I expected my host family to be much more involved, I actually favored the relatively “hands-off” attitude of my host family. My own space allowed me to build my own schedule and exercise my own independence, reaching a great balance between personal freedom and reliance upon my host family. For instance, weekend adventures during my time in Radolfzell became nearly habitual, and I was able to notify my host family in advance that I would be heading off to Freiberg, Konstanz, Stuttgart, or even Zürich, Switzerland, and Straßbourg, France with peers from the language institute.

My independence and self-reliance bloomed during my SLA study. I was able to undertake adventures safely, experience once-in-a-lifetime sights and travels, and still prioritize my studying and learning. My time abroad accelerated my blooming independence and self-reliance that naturally has grown throughout college, which only prepares me better for my following years at Notre Dame. I am confident in my ability to tackle both expected and unexpected challenges while also taking care of myself and nourishing my faith, future opportunities, friendships, and enjoyment in life.

Monday through Friday I would attend the Carl Duisberg Centrum (CDC), just six houses down the street (the location of my host stay was truly perfect for walking to school, to the Altstadt / Old Town, and to the Bodensee. My classes started at 8:30 and ended at 13:00 on Mondays through Thursdays or 12:00 on Fridays. Each day we would have a half-hour break, which I would usually spend chatting with other students or grabbing a coffee nearby. After class I would return to my homestay and prepare lunch for myself to later study, meet with friends, take bike rides, and so on.

At CDC, I encountered some unexpected frustrations with my language study. Upon arriving, I was informed that they were not offering my course level anymore, as two other participants could not obtain visas in time to travel to Germany. Therefore, I was put into a course below my level, which tested my motivation and concentration. I did not feel challenged, and many of my classmates surprisingly did not actively participate or even attend classes regularly. However, I still recognized the value in the class for me—I could shore up gaps in my language learning, grammar, and vocabulary and smooth over anything I had accidentally misunderstood. After four weeks, our course officially progressed to the C1 level, which comfortably challenged me. Two new classmates who attended German Gymnasium (high school) arrived for a week or two, adding new energy to the class, and I learned a lot from their excellent speaking and vocabulary. For the remaining few weeks, our teacher unexpectedly changed, but our new teacher was very passionate about engaging us in conversation and teaching us to mastery, which I really enjoyed. This was my favorite stage of classes at CDC, for I felt that I was able to not only learn new information but also process it well and master it. While at CDC I elected to take the telc C1 examination—the level required to study at German universities and apply for interaction-intensive job/internship opportunities. I simply wanted to test my ability, and though I was nervous as the exam approached, I actually enjoyed taking it and felt confident.

My favorite part about CDC was the fellow students—from nearly every corner of the world, with different backgrounds and stories. We all were experiencing the commonality of being foreigners in Germany, navigating the language and culture. Therefore we experienced a strong sense of camaraderie and formed solid friendships quickly.

My moderately long summer study allowed me to develop a routine in Radolfzell, further establishing a sense of belonging and comfortability in Germany and German society. For instance, I rented a bike from CDC and would go on biking adventures, as well as just biking for errands. I joined a gym and would go on weekdays before my classes. I would regularly frequent certain cafes after classes (often with Sarah Van Hollebeke, another SLA participant!), becoming familiar with the staff and owners and often having pleasant conversations. A small town like Radolfzell accelerated a fairly easy adjustment, as it was easy to navigate and easy to explore. More opportunities for eating, shopping, and entertainment were nearby in Konstanz and even Zürich, Switzerland (about 1-1.5 hrs by train). For instance, I saw Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro in Zürich: an absolutely amazing experience, especially for me as a musician.

During holidays or weekends, I would go on day or weekend trips with friends from the language institute to: Freiburg (three times!); Hohenzollern Castle; Oberammergau; Linderhof Palace; Stuttgart; nearby Konstanz and Insel Mainau; nearby Singen; Meersburg; Triberg in the Schwarzwald (Black Forest); Ulm; Strasbourg, France; Zürich, Switzerland; Mount Rigi, Switzerland; Schaffhausen and Rheinfalls in Switzerland; and Mount Säntis, Switzerland.